Let It Be Unnamed

Thoughts rabbits, lost tapes, and the dangers of remembering.

Time moves in one direction, memory another. We are that strange species that constructs artifacts intended to counter the natural flow of forgetting.

William Gibson, Distrust That Particular Flavor

What if the stories we loved as children found a way to love us back?

As adults of a certain generation long steeped in nostalgia, we are told to be hungry for the comforting embrace of simple two-dimensional animation and sweet-faced mascots. What if we could once more find the peace of sun-warmed carpet and afternoon cartoons on CRT televisions? What price would you pay for that peace? And could you live with that price once paid for your own comfort?

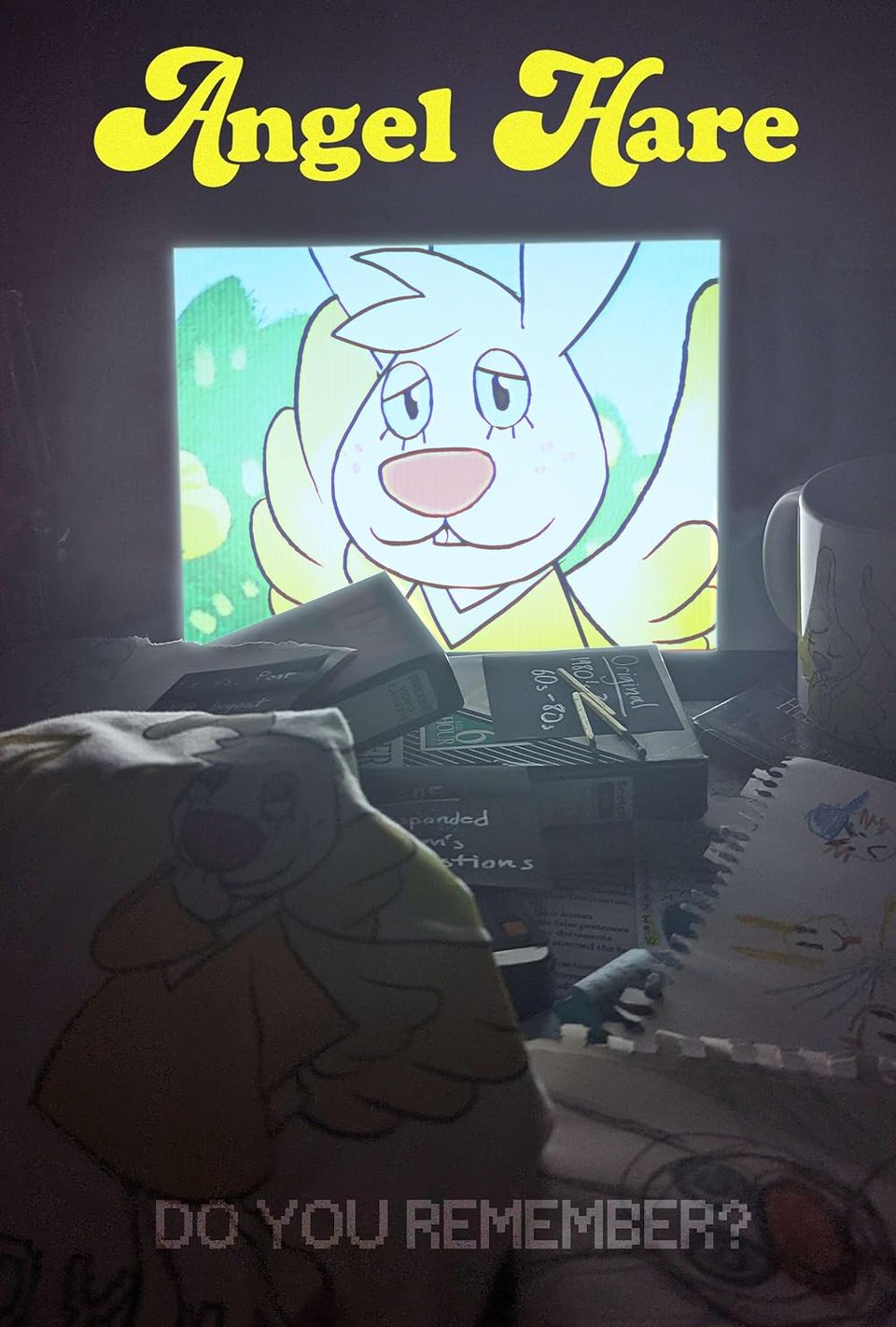

This is the premise of the analog horror web series Angel Hare by the independent animation studio, The East Patch. Well, there's a bit more going on under the hood of this short, briskly-paced online project, but nostalgia is where we begin. As someone who's wrestled a fair bit publicly with pasts both real and imagined, and the strange things found when looking back into childhood with clear eyes, Angel Hare feels like it came out of nowhere to punch me squarely in the face.

And I mean that in a fully positive way.

Created by twin sisters Hannah and Rachel Mangan, Angel Hare uses all the tried and true hallmarks of the analog horror genre to tell the troubled story of Jonah. That might mean nothing to you if you're unfamiliar with the general analog horror scene. It's a style of horror storytelling in video format, based on the use of analog technology. Think grainy, eerie, otherworldly footage of dubious origin, compiled and used to convey a sense of tension and dread rather than a traditional linear narrative. Something like Local 58, CH/SS, or Gemini Home Entertainment should spring to mind. Local news broadcasts, found footage, shaky home video. That kind of thing.

A slideshow-style narrative contextualizes Angel Hare’s plot as a series of short videos produced and uploaded to YouTube by Jonah. They are created and shared to document the discovery of his favorite childhood television show on VHS tape at a thrift store. It gives the stilted effect of projects like Monument Mythos by Alex Casanas, The Mandela Catalogue by Alex Kister, or The Greylock Tapes by Rob Gavagan, removing the protagonist or narrator and replacing the role with exposition delivered by in-world media. The story is being told to you through the medium of technology on a screen, as the plain text is overlaid with the audio and visual components of the narrative being explained.

It's jarring if you're not used to stories being told through so many degrees of abstraction, but the Mangan Sisters are very confident in their presentation of the material such that it doesn't feel so strange. You get a sense of Jonah right away, his voice and temperament, despite not seeing or hearing him on screen until well into the series’ runtime. This also holds Jonah at a distance from the viewer, his full interiority never exposed to us without a physical presence to observe, while we are shown only what he sees, the images shared on our screen.

The titular Angel Hare is a children's Christian catechism series, an altogether crunchy, low-budget educational product. It follows the rabbit angel Gabriel and long-suffering badger Francis as she walks both her companion and the audience through biblical lessons and allegories. The characters are pleasantly rendered and very cozy, with inviting voices and a sweet sort of dynamic that is immediately disarming. Angel Hare, the fictional web series itself, is an investigation into Jonah's memory of the show and perception of childhood events when he takes the videotape home and realizes how much it differs from his own copy, recorded off a local TV station broadcast.

The differences are unsettling. They are personal in ways that simply don't make sense for a show to have been different for Jonah, even one half-recalled through the bleary years since. Gabriel, known fondly as Angel Gabby, was a source of warmth, comfort, and instruction when Jonah was a very small child, home alone with his television. She called him by name and spoke so gently to him, as if she was in the room. She knew things no one else did. Gabby was his peace when there was danger in the home, and she was his strength when he had to find ways to survive it. And as an adult, Jonah now understands that Gabby, his Gabby, was real to him in a way she wasn't for anyone else.

I won't go much further than that in my description of the plot. It’s worth watching for yourself. I've seen people throw around the term “analog drama” to describe the series, but I find it deals with discomfort and ambiguity in a way that feels like horror. Clocking in at only about an hour across its two seasons, Angel Hare is a remarkably lean and effective little bit of eerie fiction. Yet there is a lot to love here, such that I've watched the series at least three times now at time of writing.

The East Patch team have a masterful grasp of tone, crafting a compelling narrative that blends heartfelt sentiment, well-timed jokes, and genuine unease without snapping from the strain. There are no jump scares or scary imagery, instead mining the discomfort from the conceits of fractured memory and fourth wall-breaking children's media, and doing so for all they’re worth. Though I've learned there is a re-edit of the first season that replaces the text-driven elements with traditional live action scenes, I do think the use of text, 2D animation, and bits of live action footage together is handled effectively overall.

The score is great and the voice cast is fantastic. In particular, Stephanie Varens’ performance as Angel Gabby strikes a balance of warmth and underlying melancholy, delivering lines that are at once sincere and ominous. Much of the music draws on old, slowed down, garbled doo-wop tunes, like taking the stylized vintage childhood aesthetics from movies like The Sandlot and drowning them in a shallow pool. This works well to make the series feel out of time, like something remembered from a movie or overheard at your grandparents’ house, as Jonah would have grown up in the 1990s or 2000s, not the 1950s. Everything feels off, and effectively so.

I think what keeps me coming back to Angel Hare is less the obvious text of the series and more of what is left unsaid. Jonah is a traumatized adult learning that his childhood was far more violent than he remembered. While certainly moving (and relatable as a once traumatized child and now adult), I don't quite think that's all the story has to say on the matter. He turns to the familiar comforts of that childhood through the mascot Angel Gabby, but out of a childlike dysfunction and dependency rather than nostalgia that we tend to think of it. There's something wrong here. You know? Something off. The way Jonah stops questioning the how and why Angel Gabby exists for him the way she does. The way we all take Gabby at face value.

For what it's worth, I don't think there's a particularly interesting “Gabby was really a malevolent force all along” reading of the text to be had. That's kind of bland and isn't really supported by the events of the plot. There is, however, a lot of uncomfortable ambiguity woven throughout the story that isn't resolved in any concrete way by the end of the runtime. This is praise, of course, because I think it lends a palpable unease to the wholesome comfort that Jonah experiences and Gabby singularly embodies.

What is Gabby to Jonah? She is his self-proclaimed guardian angel, but she isn't his mother, or some ancestral spirit, tasked with watching over him. And what is Jonah to Gabby? What does that lack of direct connection to Jonah say about the lengths she is willing to go for him? We understand why Jonah would cling to the avatar of his comfort, but it is fascinating how quickly he abandons the mystery of his past to focus solely on Gabby and his relationship with her. The narrative toys with the idea of what we get out of fiction, especially what we take from those comforting childhood narratives, but it raises the question of what our narratives get out of us in turn.

Over the series, it becomes clear that others know what actions Gabby has taken with Jonah. Or, at the very least, someone else seems to know what she's done acting as the guardian angel of other children. Francis steps in for the interstitial “Letters with Angel Gabby” segments to field questions from viewers -- of the web series, that is, not the in-world cartoon, further obscuring what is and isn't explicitly “real.” During these segments, he nervously asserts that Gabby is just too busy with her angelic duties to read fan mail, and dodges any direct questions about angels and other supernatural beings with folksy platitudes. Yet Gabby is shown receiving an ominous letter (“What did you do?”) from someone named Nathan, a message which leaves her distressed. When further pressed by a fan about Gabby's relationship to Jonah, Francis “glitches,” for lack of a better term, as the fabric of his form bends and breaks before the footage skips past his answer entirely.

With the extremes that Gabby appears to have gone in her efforts to protect and nurture Jonah, what does this say about her actions? Any apparent knowledge Francis later displays about the broader machinations of the Angel Hare universe and Gabby's place within it is met with some degree of frustration and dismissal by Gabby. How does that color the goodness we see radiating from Gabby when depicted by Jonah as his loving guardian?

And in rejecting the realization that he and Gabby did something very dire when he was a child, what can we say about Jonah today? Does that truth matter? Do answers matter? Can we really trust that what Jonah is showing us is reliable if he is incapable of facing his own truths, especially where Gabby is concerned? How am I supposed to read her agency and actions when they appear to go unquestioned by the world and the characters within it?

I don't know. I'm glad that I don't. Those stains of doubt keep the otherwise wholesome narrative from teetering into cloying sweetness or simple, nostalgic wish fulfillment. I find myself as unsure as Jonah is, as unsteady on my feet as I look at every piece of evidence before me. And I am also as captivated by Gabby as he is, as soothed by her warmth, by the promise of an unwavering devotion. An answer at the end of the day.

There is something in it that feels familiar. I think there's a very intuitive reading of Angel Hare as a contemplation on one's relationship to the Christian God -- or, perhaps more importantly, the Christian church. One may find comfort and meaning there, in the rituals of prayer and devotion, but is discouraged from questioning the authority of church leaders and God the Father who imbues the leaders with that authority. The act of questioning can be met with disapproval or censure. I get that, given that Gabby is an angel in an educational children’s cartoon, acting as the vessel of God’s teaching and the church’s authority. Even the act of questioning, of having one's world shaken, is deeply, irrevocably destabilizing on its own without the necessity of punishment.

However, I see Angel Hare as a fascinating encapsulation of the relationship between a parent and child. Through Jonah, I feel like a child, turning to a parent for comfort and safety, and being met with the complexities of their rules and the strangeness of their moods. A child cannot grasp that a parent is a person with their own secrets, lies, and problems. They are a deeply flawed being making choices the child won't understand for years to come. If ever. If these choices can ever be justified.

Gabby's seemingly unchallenged authority is disorienting when there are such consequences for breaking her unspoken rules. Yet in the next moment, the next line she speaks, she melts into softness once more. As children, our survival -- our conception of reality -- depends on disregarding these moments of destabilization or inconsistency. It's better to remember your parent as loving and caring rather than messy and complicated, and even sometimes cruel.

At least, this is what I've learned in therapy over the years.

Gabby is not evil, but she is far from perfect. Seeing how Jonah sees her, I think of my own uneven relationship with my mother. I think of the things I tried to forget or smooth over in my mind. The kind words that I focused on instead of the ones that upset or confused me. Like Jonah, I came to understand her imperfections in adulthood through a long process of reconciliation. And just as in that process, Jonah is left with a lot of uncomfortable ambiguity in his relationship with Gabby, coming to difficult, but ultimately necessary, conclusions for himself.

Whether taken as a cozy analog drama or an eerie piece of horror, Angel Hare has kept me fascinated for weeks. I find so much to tease out in its unanswerable questions and uncomfortable ambiguities. Even if analog horror isn't your usual thing, Angel Hare is well worth your time for all the things it doesn't say.

Add a comment: