I Grieve in Stereo

I grieve in stereo

The stereo sounds strange

You know that if it hides

It doesn't go away

When I get out of bed

You’ll see me standing

All alone, horrified

On the stage

My little dark age

There is a scene from the video game Galerians: Ash that has lived rent-free in my mind for the last twenty years. I think about it more often than I probably should. That may or may not reveal something about me, but we won't dwell on that for now.

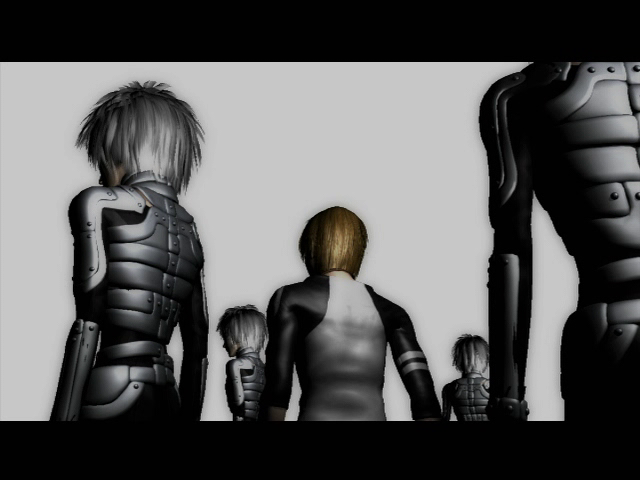

The scene shows a young man in an empty terminal lobby, a dull, cold metal space with sallow artificial light. He is lanky and blond, made of sharp angles rendered in knife-like points by the day’s hardware. A line of four clunking, stamping robots stand before him. Their bulky frames are piloted by what are revealed to be human fetuses rigged with wires and cables. These things, made from the interface of flesh and machine, speak in small, flat mechanical voices as if of the same mind. The same voice.

“He came,” they say.

“He's here.”

“We've been given these ugly bodies because of you.”

“It's all your fault.”

Raising their arms, these unnerving heaps of junk and human parts say in unison, “We'll give you a taste of our suffering.” Then they fire their weapons.

It’s a strange scene. The peculiarity of fully sentient fetuses inside giant robot suits can skew from upsetting to absurd depending on your mileage. For me, more unnerving than the idea of this disfigured humanity is the knowledge that these things, these weapons willed to life against their express desires, feel pain. They are suffering and are cognizant enough of that suffering to vocalize it.

Eerier still, they can identify someone to blame.

This is why I've never been able to stop thinking about Galerians: Ash, even after all this time.

First Cycle

Galerians: Ash is a PlayStation 2 survival horror psychic action game developed by Polygon Magic. Those words may or may not make sense if you didn't read my last essay on this stuff. That's okay. You can read it here.

When you fire up the game on your PS2, the names of lyricist/series writer Chinfa Kan and mangaka/character designer Shou Tajima are once more on the main menu. They are stamped next to the copyright symbol just as in the first game so that you know up front that Galerians is the product of their collaboration. First game director and scenario co-writer Hiroshi Kobayashi returned to direct. Scenario co-writer Ichiro Sugiyama came to the sequel as a producer and writer alongside Kan. Tajima served as character designer and graphic advisor with the first game's art director Masahiko Maesawa returning as a monster designer and in-game animation director. Composer Masahiko Hagio returned as the sound director.

Ash was released in Japan in April 2002 by Enterbrain, North America by Sammy Studios in February 2003, and across Europe by Sammy Europe in March. Galerians: Ash is the sequel to the 1999 PlayStation game and the 2002 OVA Galerians: Rion. I say this because it draws strongly on the overall aesthetic and animation style of the OVA and uses segments of the series for the prologue and flashbacks throughout the game. This isn't to say that Ash feels ashamed of its lower fidelity PlayStation predecessor. It makes for an interesting sort of visual continuity across the OVA and sequel, in that the team fully embraced the leaps forward in hardware capability made between games.

That said, I think to call Ash a sequel feels a bit odd, at least in the contexts I've seen it employed. Galerians: Ash has historically been characterized as a misguided follow-up. It was broadly panned upon release, and in the years since, I’ve seen it called totally unnecessary. Rion's story, for all its bumps and bruises, was over. He needed to stay dead.

Based on archived reviews and the content of more recent YouTube series retrospectives, the consensus is basically what I understood it to be during my time in fandom spaces of the time. Ash undoes the hand-won battle against Dorothy and renders Rion's sacrifice hollow. We could at least believe that Rion may have been a real boy lied to and manipulated by Dorothy at the end of the first game, but now we must deal with this clone walking around muddying up the place. It manages to dampen the lonely, moody successes of the first game, making that game worse by association.

To me, however, and the one other defender that I have personally known for twenty years (shout out to Elendraug if you're reading this!), it is the perfect complement to the first game. I would go so far as to say that Ash not only explores the themes and ideas at work in Galerians, but it also helps me gain a deeper appreciation for these ideas in seeing how they mature. This story is stronger and feels more full, more developed, when taken as a single narrative split in two with an OVA in the middle for fun. My research into the game’s development is hindered by dead links and language barriers, so I can't confirm or deny the veracity of that claim, but it feels true to me as a player.

The tension underlying my thoughts and feelings on the matter comes from how starkly Ash differs from its predecessor. When and where Ash's mechanics break from the standards established by Galerians, itself a fairly clunky, dated example of survival horror game design of the 1990s, I feel the game frequently stumbles. Those soft spots were ugly and aggravating enough to put off a lot of players and reviewers back in 2003.

Because Galerians: Ash is a slog. A bore. A chore. An unfitting end to a series with a distinctive vibe and vision. And while I am empathetic to how some design choices can alienate players from the experience, I don't agree that these choices constitute a failure on the part of the development team.

Ash asks that you meet it on its level for the game that it is and accept that its mechanics and strangeness function to create a mood and tone. Through these experiential elements, the feel of a harsh 3D space and the sensation of pressing buttons to move through its polygons, the game conveys its themes to the player. I think that's worth talking about, because I think what it has to say is worth talking about, even as I haven't been able to find much in terms of reviews or forum posts from people who seem to agree.

All of this to say that if you need Rion Steiner to die and stay dead in order to fulfill his role as a hero, I’m here to ruin your day. Galerians is not a story for heroes but those living in the margins of some grander narrative, drawn into the fray against their wills. If Galerians is about anxious children waking up to the horrors of the coming future, Galerians: Ash is about the adults they become in a future they never wanted, forced to live in a world they hate and fear. They are the children of failed gods and parents, raging still against their makers on a planet that bears the scars of intergenerational violence.

So let's just finally talk about it.

Second Cycle

I can tell you where I was when I first played Galerians. I can recount holding the heavy triple-disk plastic case, thumbing through the glossy paper of its slim guide. How it felt to hold the controller, my bare feet on the blue-gray carpet of my parents’ living room, hunched forward on the couch as I anxiously pushed Rion through the halls of Michelangelo Memorial Hospital.

The first game came into my life when my mother found it on clearance at Target, tossed on a shelf or in a bin for a few dollars. Its sequel, to this day, I have no memory of the how or when I found it. These were the days before two-day Amazon shipping and endless scrolling through online commerce superstores. I probably had to call around at the Best Buys or Circuit Cities of my shabby corner of Fort Worth, tracking it down the old-fashioned way.

How old was I? How many dollars did I scrape together to buy a PlayStation 2 game in the years after 9/11, when my family was spiraling in the wake of my father losing his airline job? My mother was waiting tables and tending bar to keep the lights on. I used to come to the restaurant with my mom and clean tables for a few bucks here and there when the manager wasn't around. The first game was a pleasant surprise. The second must have been hard to get. That's probably why I don’t recall much from those days.

What I do remember is playing it. Alone on the couch, holding the controller, holding my breath. Moving through the corridors of the air terminal. Feeling incredibly small. Powerless. Powerful, of course, in the moments when Rion's long, sharp body tenses to release a volley of psychic energy, but only then.

A few seconds of reprieve before returning to the loneliness of being Rion in an empty hall, an empty room, my living room, my own troubled home.

Playing, finishing the game, then starting over a few days or weeks later. Playing, never finishing the game except when I did, and feeling too sad to leave the console off afterward. Playing again and again and again, as if I would find a new ending if I tried hard enough.

I never did.

Third Cycle

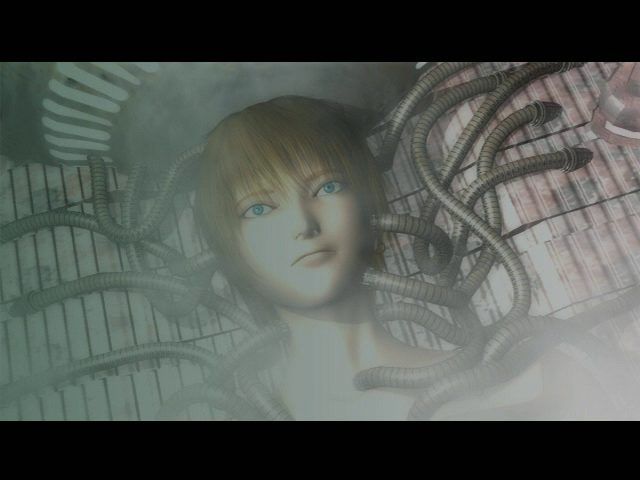

In the six years since the events of the first game, Rion Steiner has descended into hell. Though dead to the real world, he lives on, repeating the last hours of his life as data in Dorothy's backup files. He loops through his and Lilia's ascent to the pinnacle of the Mushroom Tower, fighting the same twisted, gibbering Rabbits and hulking Battle Droids. They find the same womb-like pods that housed Rion’s true family -- Birdman, Rita, Rainheart, and his twin clone Cain -- and join hands to kill Dorothy, his mother-god and their fathers’ mad creation.

The tower is different compared to its appearance in the last game. No longer small and intimate, the PS2's hardware renders Dorothy's flesh and metal spire in what feels like impossible geometry. These spaces, once claustrophobic and anxiety-inducing, are now colossal and alien. Less organic than we remember, with the crawling veins and exposed red muscle tissue, and more mechanical and surreal. Rion and Lilia are dwarfed by these spaces, their small and crunchy figures made to look all the more fragile beneath strange ridged domes where electricity crackles from unknown points of origin and means that make even less sense.

Once more, Rion hears Lilia's voice in his mind, but not the Lilia beside him. He is tracked by a probe, a sphere covered in rods that spins and sparks white light. The voice that emerges tells him that she is Lilia from the future, that he is a ghost inside a dying machine, and that only she can revive him. For the player, this reality manifests as a loop twice run, a tower twice climbed, and a Dorothy twice defeated. But it is also expressed in Rion’s character.

This is not the silent, thoughtful young boy from the first game, played awkwardly but earnestly by Frank Newman. This Rion has more in common with the more brooding and expressive one of the OVA, played then by the snarly David Wittenberg and now by a tonally confused Johnny Yong Bosch. It creates a notable dissonance, for better and much worse.

Lilia is now voiced to perfection by Bridget Hoffman, replacing the OVA's Kari Wahlgren and Julie Maddalena from the first game. Hoffman brings a reserved, breathy quality to her voice work. It often feels as if Lilia is cutting herself off, taking a breath to keep herself from saying, admitting, more than she already has. It's a mournful yet guarded performance that stands out as one of the highlights of the game for me.

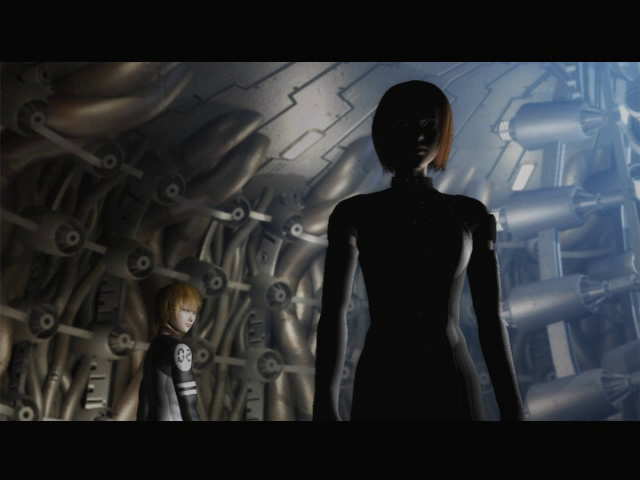

When the future Lilia reaches back with her probe one final time, Rion places his trust in his friend. He completes the loop and confronts Dorothy, promising Lilia, his Lilia, that they will reunite in the future. Then Rion dies and is resurrected in an adult body, emerging from a cryogenic chamber in a strange false birth.

Freezing air blasts like white smoke and machines whirl as his tube is spewed out by the machine keeping him alive. Lilia is now a scientist like her father before her. She froze Rion's body after his brain died, keeping him in the bunker she's been working from. One day, she would revive him. This is not how she wanted to do it.

Rion is a dutiful corpse, leaping to serve Lilia as she explains what has come of the world since he left it. Michelangelo City fell after they uploaded the virus into Dorothy's system. Everything collapsed without the city's artificial intelligence to manage its affairs. Worse yet, Dorothy's contingency plan activated upon her death. unleashing the Last Galerians on the humans.

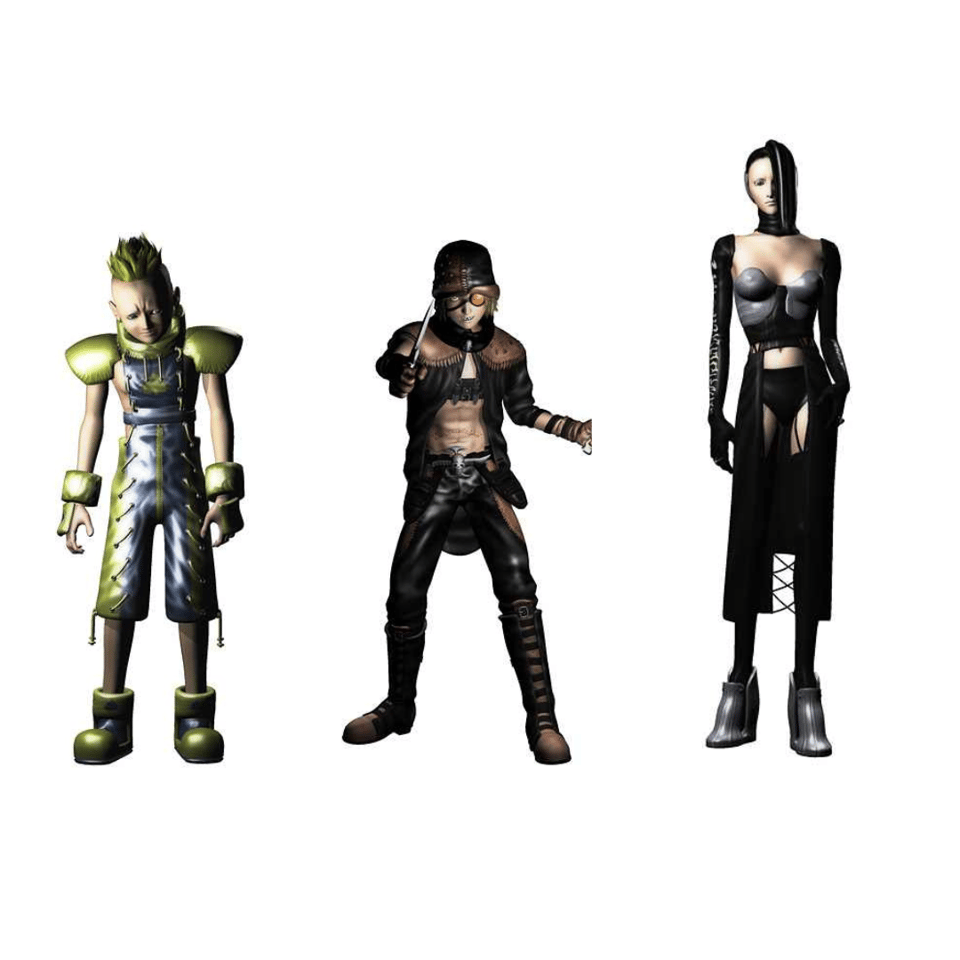

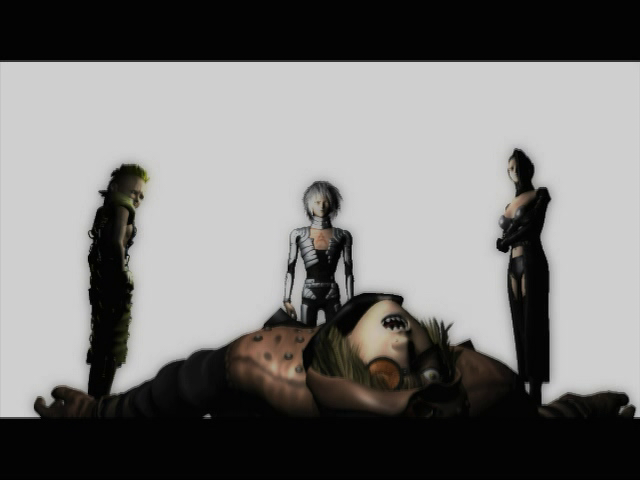

Her new children are much nastier and more volatile than the last. There's the young and timid Spider, who curses Rion for forcing him to be born in such a miserable world. The sadist Parano cuts up bodies and performs experiments on any humans he kills, tearing out their eyes to stuff the sockets with cybernetic parts. The nihilist Nitro savors despair and casts illusions to wear down her prey.

They are led by Dorothy's greatest blight, Ash, a walking nuclear reactor whose powers are amplified by consuming waste uranium. Ash exists solely to revive and restore Dorothy, operating from the shadows of the uranium refinery where no human can safely tread. From here he wages a bloody war against the humans he loathes and leaves an irradiated wasteland in his wake.

Lilia has spent the last six years searching for a way to stop Ash. Digging through data from the corpses of the Rabbits and Arabesques now produced by Ash, she discovered a crack in their defenses. All things birthed from Dorothy's lineage are weak to the virus created by Lilia and Rion’s fathers. That virus program was lost when Rion’s brain crashed.

The mission was clear: recreate or retrieve the virus from Dorothy's back-up files in the Mushroom Tower and deliver it to the military now controlling Michelangelo City. While the military wanted to use the virus to destroy Ash’s army, Lilia knew the only way to do so was to retrieve Rion’s consciousness and put him back in his body. His Galerian body, whose augmentation makes him resistant to Ash’s high radioactivity.

Only the children of Dorothy can kill one another, she laments. Rion, perhaps a little too easily, agrees.

This is no longer a scared boy faced with violence but an adult knowingly seeking it. Rion, the mistake who murdered his mother-god, is now going to do the same to the brother who was born to resurrect her. Lilia can only offer Rion her grief for condemning him to this ruined future.

The Last Galerians launch their attack.

Fourth Cycle

From the opening level to the expository reunion between Rion and Lilia, Galerians: Ash just...feels different. It’s disorienting in a way that mirrors the first game's cold open and amnesiac protagonist. Nothing makes much sense, this time relying on the disparity between the level design, atmosphere, and characterization to evoke unease. The vibes-only nature of the science fiction just feels all the more untenable, whether through the softness of the world-building as a whole or the choppiness of the English localization.

Yes, we're back in the chrome future of the psychic child combat game, killing gods and monsters. Yes, we still love scientists explaining the story to us. Yes, the plot is held together by twigs and string. Yes, the voice acting is highly questionable.

Now, when it comes to Johnny Yong Bosch's performance as Rion, I’m an unrepentant hater. I’ve liked Bosch just fine since he started doing English anime dubs in the early 2000s, but he turns in a distractingly bad performance here. Bosch wavers between smug anime boy attitude and a flat, detached affect, neither of which feel fully appropriate for any given scene. I chock this up to poor direction and editing more than anything else. The criticism applies to most of the cast, which features a roster of seasoned character actors. There's talent here, it just isn't used very well.

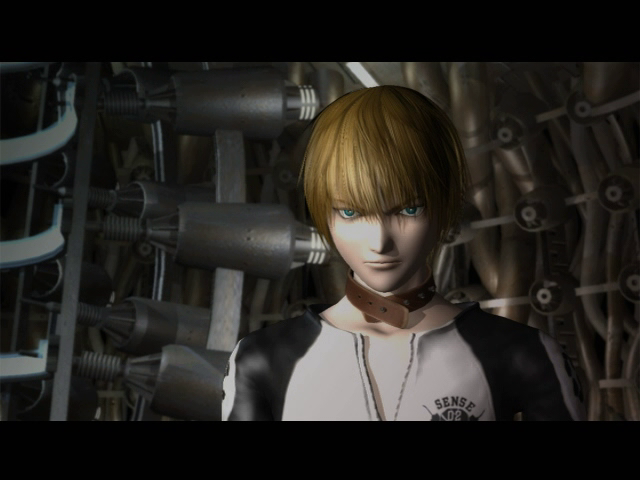

I understand the need to differentiate between the Rions of each game. Newman was not great, but he made me believe that he was an amnesiac teenager trying to survive a world trying to kill him. His voice was young and he seemed truly out of his depth. This Rion has an adult body and a teenager’s mind.

He dresses in an aged-up version of his previous look with a zippered black and white raglan shirt, brown trousers, and tan boots. The black choker has been replaced with a loose brown leather collar, his wrists and hands adorned in bracelets and rings. Seemingly meaningless insignia is printed on the front and cropped sleeves of his shirt to give him a sportier look. His shirt is unzipped at the collarbones and taut belly in opposing Vs of exposed skin, a little slip of sex appeal to show his off newfound maturity. His ear is still pierced.

Rion has also been locked in a time loop for six years with the knowledge that he's the clone of a dead boy. Conceptualizing this Rion as a little jaded, a little edgy, doesn't bother me. I think it makes sense that something inside him shifted in him. Bosch does manage some interesting line reads from time to time, giving Rion some much needed emotion to break up his generally stoic nature. But, for the most part, he's too flat to really offer anything, coming off as bored or distracted rather than engaged with the material or the content of the scene.

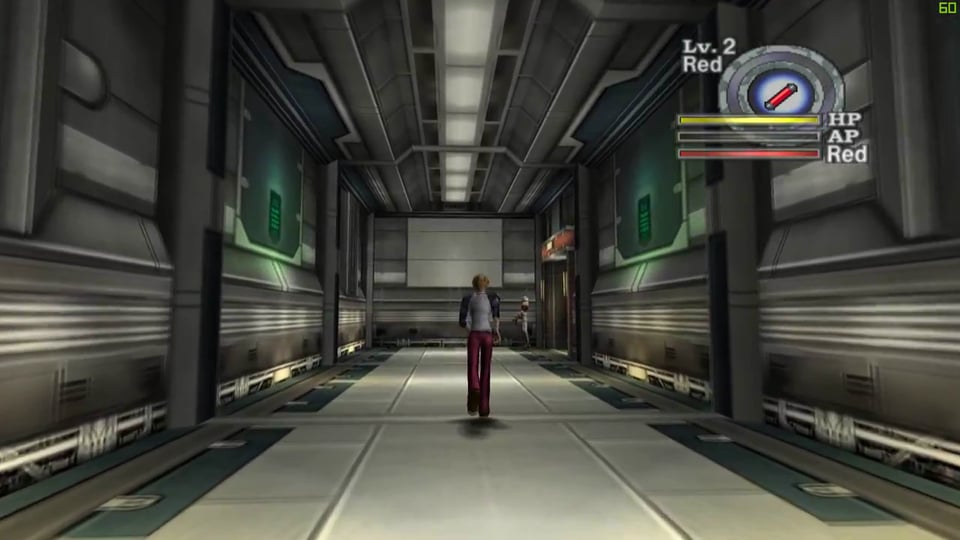

In terms of gameplay, Ash eschews its survival horror roots, tank controls, and fixed camera to test out the PS2’s capabilities. The new 3D camera is pretty smooth, allowing for easier navigation and combat than the often frustrating fixed camera angles of the first game. The psychic combat returns with the familiar Nalcon (energy blasts), Red (pyrokinesis), and D-Felon (gravity manipulation), along with a shield ability and two new PPECs synthesized by Lilia's research team. The new camera allows Rion to strafe enemies and lock on for targeted attacks, however all attacks must still be charged for a few seconds before release. This keeps you standing still and unable to dodge enemies who may strike while you're vulnerable.

Retooling the first game’s approach to combat, light RPG elements have been added to the mix, with character hit points displayed on-screen. Enemies drop loot such as healing capsules and PPECs when they die, which makes resource management easier. There is also a simple leveling system for Rion's psychic abilities, allowing you to improve or neglect the stats of your abilities as you choose. These aren't particularly impactful changes and the game doesn't fully commit to rounding out the new elements, so it ends up feeling pretty shallow.

Combat is still clunky, not especially fun, and certainly not empowering. Rion's powers function essentially the same way as the first game, with an additional layer in the shield function. There's a rush of satisfaction that comes from burning a room full of advancing Rabbits or blowing up a squad of Battle Droids, but combat is something that you survive, not enjoy.

Attacking enemies or taking damage from enemy encounters causes Rion's AP (addiction points) meter to fill. So too does using his shield to protect himself from enemies. Once the AP meter maxes out, Rion experiences a brain short. This heightened state unleashes all of his power in a continuous wave, exploding the heads of all nearby enemies. It also slows Rion to an agonizing crawl as this power gradually kills him, draining his health until death.

While shorting can clear an area of enemies, it can't kill level bosses, making it useless in high-stakes battles. The effects can only be alleviated by using the drug Delmetor, which you will need a supply of during boss fights. You spend the game timing these brain shorts and managing your resources to hopefully minimize their damage on yourself. I've always found the idea of punishing Rion for using his powers to defend himself a compelling way to convey the themes through mechanics, but the addition of the shield absolutely delights me. Not only is Rion punished for engaging in combat, but he's also punished for protecting himself from aggressors, as little else in the game fills the AP meter like using the shield.

Kicking your ass for playing an action- oriented game sounds unreasonable to some, but these mechanics are fascinating to me. Equally off-putting when compared to its predecessor are the levels and environments and how Rion traverses them. Galerians offered players four distinct and self-contained stages, each with their own tones, aesthetics, scores, and overall vibes. The space-age gleam of steel and white fluorescence made the Michelangelo Memorial Hospital level a completely different experience from the drafty Art Deco of Steiner Manor, the mid-century grime of the Babylon Hotel, and the H. R. Giger-inspired womb chambers of the Mushroom Tower. For both good and ill, Galerians: Ash is far more restrained in both its visuals and ambiance.

There are only really three locations in the game. Four if you count the digital spaces that Ash haunts, but we'll put a pin in that for now. The first is the reimagined Mushroom Tower, which Rion frequently returns to throughout the game. The second is the abandoned air terminal where the army has set up as a base of operations and Rion awakes in Lilia's care. The third is the uranium refinery where Ash operates from. There are no outdoor, urban, or suburban spaces here, just metal corridors, oblique architecture, and artificial light. Gameplay in these levels is defined by light puzzle solving and a respectable number of enemy encounters, many fetch quests, and a great deal of backtracking.

Rion's life is a loop and so is the game he finds himself in. The atmosphere of the first game was tense and oppressive, moving through sterile hallways or grungy hotel rooms, each empty, hostile area oozing a palpable dread. Here, the familiarity of human spaces -- plush hospital offices, homes with kitchens and bedrooms, hotels with recognizable features -- is ripped away. There is nowhere to sit or rest. The airship base is too big for people, with huge, snaking corridors and bay doors opening to yawning offices stripped of any social context.

Everything here is barren. No windows. The sickbay looks alien. The makeshift armories are almost depleted of ammunition. There are boxes of useless cargo and supplies tossed around to imply a functional space now lost to decay. Scared, angry, and tired, soldiers sit huddled against walls to sleep or gather around to chatter or lament their circumstances. Rion goes from soldier to soldier during the many hours spent here as the hub level. He must initiate conversations to receive direction, find clues to advance to the next objective, or gain context to use necessary items. Some soldiers talk in circles. Others threaten to shoot him or long for the war to end.

There doesn't seem to be any real strategy to choosing this as a base of operations. Ash’s army attacks frequently enough that they’ve captured parts of the terminal. These areas are lost, quarantined behind sheets of metal soldered to the doors. Parano is able to get inside and turn dead soldiers into cyborg zombies under his control. The army has no food, no crew quarters, no mess hall, and no plan. It's miserable, and it's miserable to play.

Rather than progressing linearly through stages, Rion cycles through them with each puzzle or fetch quest. Get an assignment, find someone to give you directions, locate a keycard, solve a random puzzle, fight a boss, then repeat. Major battles between the humans and Galerians happen largely off-screen because they don’t concern Rion. They aren’t for him to involve himself.

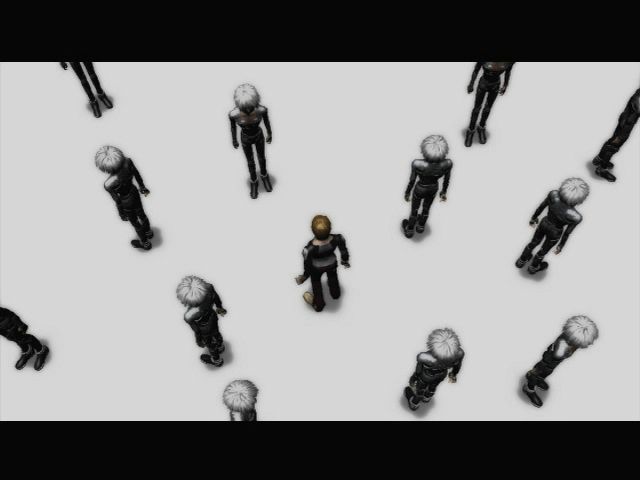

Looping through the empty halls of the base, then the industrial hellscape of the uranium refinery, then the digital recreation of the Mushroom Tower. Looping through tasks, through combat, through travel. Rion is a lone figure in the center frame as the game camera sticks to his back, swallowed by spaces totally hostile to human life. Everyone and everything is so antagonistic to Rion that it goes beyond eerie to land squarely in the existential.

I can see why players are put off by the repetition and often aimless wandering. For me, there is an experiential value. It feels deliberate rather than an oversight, though some of the backtracking does add unnecessary padding to an otherwise modest runtime. Traversing these inhospitable areas by foot and completing menial tasks makes me feel connected to Rion as a character. Purposeless, rudderless. Alone.

Left with only my thoughts, I zone out to the uneasy peace of Masahiko Hagio’s ambient score. The drone of ominous, ill-meaning electronic music, punctuated by insect-like machine noises, makes me feel unwanted. Whereas the levels of the first game often felt too small and too tight for the bodies on the screen, Rion is adrift in a spacial abyss. It isn't fun, and it isn't necessarily painful, either. But it is lonely. Bereft of a sense of control or agency.

Run, fight, solve a puzzle. Do your chores. Do it again. Sit in the emptiness. Sit with your thoughts. Do it again.

Doesn't that seem unfit for someone who saved the world at the end of the last game?

Doesn't that seem more like a punishment?

Doesn't that kind of sound familiar, too? Doing your little errands while the world falls into despair around you, and you have such little say in the matter?

Anyway.

Fifth Cycle

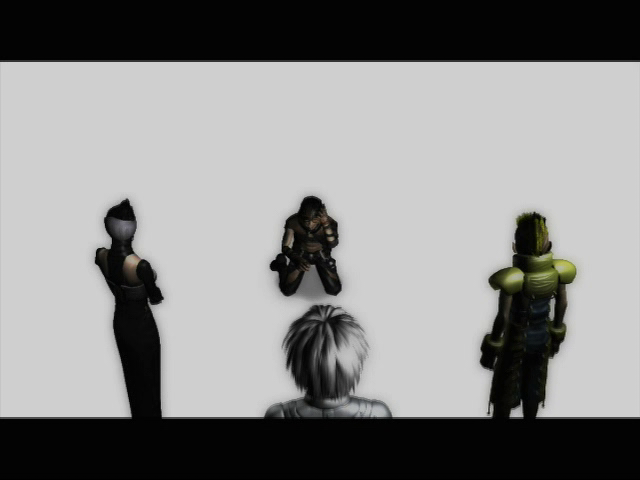

Trinities are important to the thematic and narrative cohesion of Galerians as world and concept. God, Man, and Machine. Rion, Lilia, and Dorothy. The mirroring trinities of First Galerians Birdman, Rainheart, and Rita and Last Galerians Parano, Spider, and Nitro.

Ash steps in as the chosen son and resurrector of Dorothy, acting as the savior in opposition of Rion the betrayer. Lilia stands between them to act as Rion’s tie to the human world, though the soldier Cas and child prodigy hacker Pat expand Rion's understanding of humanity.

To talk about the real meat of the game, I have to talk about Lilia, Ash, and Rion for all that they represent in the story and in relation to one another. They each hold an element of the story's heart within them, building on themes present in the last game and complicating them in interesting ways. I kind of hate talking about that, to be perfectly frank. This is the part of the essay where I can't help but get lost in the weeds of my own interpretation. I don't know what's present in the text and what I’m reading into it, overcome by the wet, sticky, sentimental film that bubbles up in my brain when I think about these games.

Is it text? Subtext? Localization? Mistranslation? Headcanon? Shipping? Millennial brain rot?

I worry I’m being too soft. I could just agree with those archived reviews and YouTube screeds. It would be simpler if I did. But if I did, I wouldn't be able to explain what this series means to me, and what I think it could mean to you if you let it.

I'm choosing to believe that this is more valuable.

Sixth Cycle

Bathed in the sterile glow of computer light inside her subterranean laboratory, Lilia wears science as an ill-fitting cloak. She's dressed in a barely buttoned white dress with black arm straps, white sleeves, a black choker and chunky black boots. Between the gaps in the black clasps holding her dress together, there looks to be a black crop top and mini-skirt. The layers are such an odd touch, but I love that they're accounted for.

The close cut of her brown bob, black choker, and oddly put-together outfit evokes Natalie Portman in Leon the Professional. It's the look, yes, but also the vibe. A literal child operating under the adult male gaze of the camera and director, Portman plays up adultness and womanness despite her very young age and palpable vulnerability. For Lilia, she feels much the same but in reverse, drawing from some of the same aesthetic touchstones but coming across as much younger than she is.

Her research into Dorothy's systems has given humanity a weapon against Ash, but to conflate that research with her plans to revive Rion denies her an essential element of her character. It's there in everything that isn't said, in the breaths between exposition and plot progression.

An accomplished scientist by her early twenties, Lilia has been motivated by survival since she and Rion destroyed Dorothy. She is an orphan in what remains of Michelangelo City. The months spent running from the Galerians as a scared teen have turned into an adulthood evading Ash and his army in an active war zone. The only thing she has is Rion. Not her Rion, but the clone who wears her best friend's face.

The details of how are as fuzzy as most of the stuff that gets waved away in a single line, but she stored his body for six years. She's taken him with her, kept him safe, kept him healthy. Maintained his growth so that they could be the same age when she found a way to fully revive him.

That is an act of devotion by a traumatized child given the capacity to make her wishes come true.

There is a possible world where Lilia could have saved it for Rion, creating a space for him to live the life her best friend was denied. Her plans to keep Rion ran parallel to her work. She studied the corpses of Ash’s army to discover their weaknesses and, at some point, synthesize the drugs that keep Galerians stable and functioning.

Creating these drugs for Rion to manage his powers stands in sharp contrast with the girl she was in the first game, horrified to see him kill someone else. Lilia is completely pragmatic in her care for Rion, accepting the violence he's capable of and giving him the most comfortable life possible.

In the first game, the use of drugs was shocking. The image of a child injecting himself with chemicals to enact violence on the adults trying to murder him unsettles me. That he and the rest of Dorothy's miserable, murderous creations are forced to fight for survival is achingly tragic when taken as abused, drugged, and traumatized children. To see the same drugs in the hands of adults, spoken of so casually and treated as a tool, left me cold for a long time. It felt like a missed opportunity to develop the themes of the first game, but the years spent with Ash have softened those hard feelings.

Lilia, in full understanding of what Rion is, hands him a beeject. She didn't want to bring him into a world so hopeless and cruel, but her work, and the world, forced her hand. Rion needs the drugs to defend himself. Lilia needs them to keep him alive. In her vision of the future, drugs are a form of love.

It's easy to take Lilia's actions as the different stages of a singular goal. Preserve Rion, retrieve or recreate the virus, create new PPECs, restore Rion's consciousness, and revive him to stop Ash. To me, this is the collision of two worlds. The one she's making for him, and the one that Ash is making for them all.

This is a great tragedy at the core of the story. Lilia hovers in the frame, the corner of her laboratory, a ghost among the glowing screens and hissing mechanical parts. She loves her childhood friend so dearly, longs for his companionship so deeply, that she makes space in her heart for a copy. There is no version of her world without Rion in it, and so she will create the circumstances through science and faith and whatever spirits she prays to softly at night to make it a reality.

And she doesn't live to see it.

Seventh Cycle

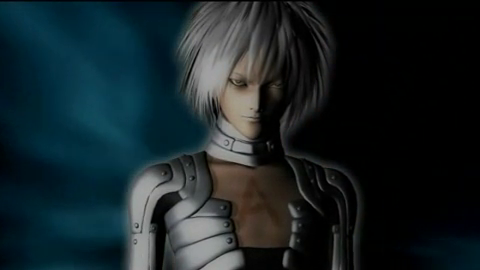

If Lilia is the quietly beating heart of the narrative, Ash is the monster waiting within its shadows.

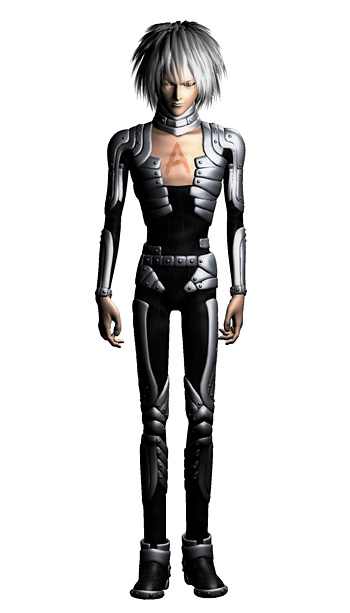

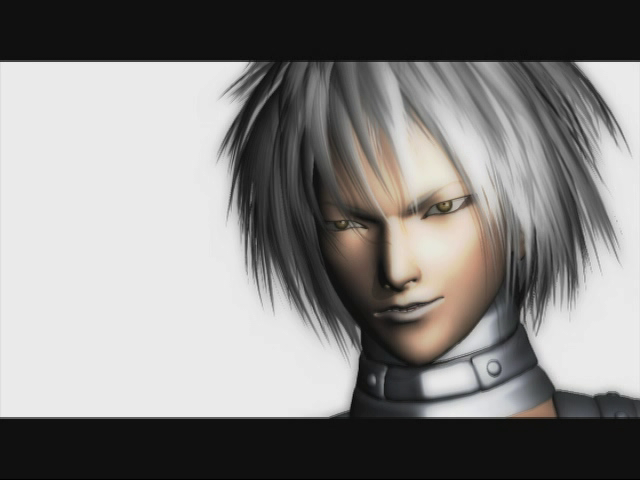

He is a shock of J-Rock sensibilities with his voluminous silver spiked hair and slim silhouette. Kan being a successful lyricist for rock and pop artists since the late 1970s shows in some of the characters and how they move. Ash's lips and nails are painted to match his silvery hair and the chunky metallic pieces encasing his tight black bodysuit. The A scored across his bare bony chest declares his identity to the world, though his bare hands are an evocative choice amid a cast of antagonists that favor some style of glove. A bare chest is an invitation to enemies to strike his heart, while bare hands imply the desire to savor violence through physical touch.

Ash is Dorothy's failsafe, a child hidden from the rest who emerges upon her destruction to resurrect her. The Family Program falls under his control, wielding his mother's army of monsters against what remains of humanity. Though only seen a handful of times in the game, Ash is a nightmare, a boogeyman who commands his Last Galerians with derision and cruelty.

“Altogether a nasty bunch,” he says of his siblings with a smirk. Spider is the stand-in for Rainheart, a young boy who hates the world he was born into and wants his family to get along. Though timid, he holds a tenderness for Ash that even his brother's cruelty can't shake. Nitro builds off Rita's misery and projects it outward, taking delight in torturing Rion through emotional manipulation. Ash is amused by her sadism, though she isn't all that concerned with gaining his favor.

The knife-wielding Panaro is a volatile character with sharpened teeth and a single a wild yellow eye, giving Birdman a run for his money. He's preoccupied with the body and bodily fluids, turning humans into his little toy soldiers through brutal experimentation. Parano trusts no one and is vocally critical of Ash, a streak that eventually sees him shot dead by his brother.

It's through these relationships that we glean much of what there is to know about Ash. Ash is a living nuclear reactor dedicated to creating a world that only Galerians can survive. He is cruel for cruelty's sake with a snide and sneering delivery to all of his lines. Voice actor David Wittenberg turns in one of the best performances of the game, with a smirk you can hear in every word, a barely contained snarl conveying his utter contempt for everyone and everything.

(It’s worth reiterating here that this is Wittenberg’s second Galerians role. He played Rion in the OVA, as mentioned above, though I don't quite know what to make of that choice. Wittenberg was totally fine as the series’ harder-edged Rion, but I do like him as Ash much more.)

Ash is camp, is what I'm saying. He's having fun being evil in a way the overly floral Dorothy could never. Tortured, yes, but he’s still dynamic and interesting with the material on the page. Ash hates the humans and he hates the Galerians and he hates, hates, hates Rion most of all.

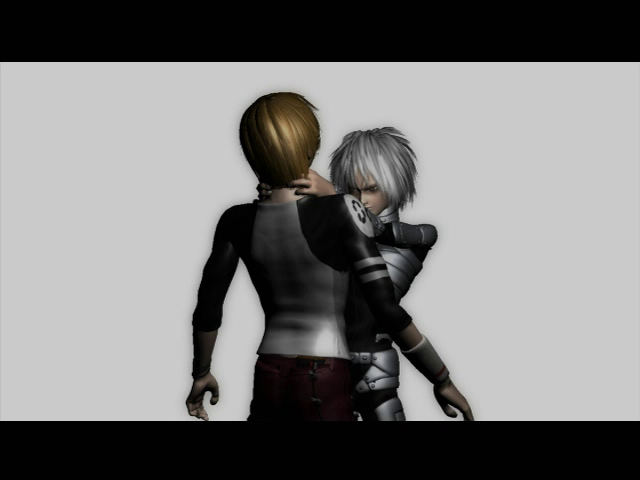

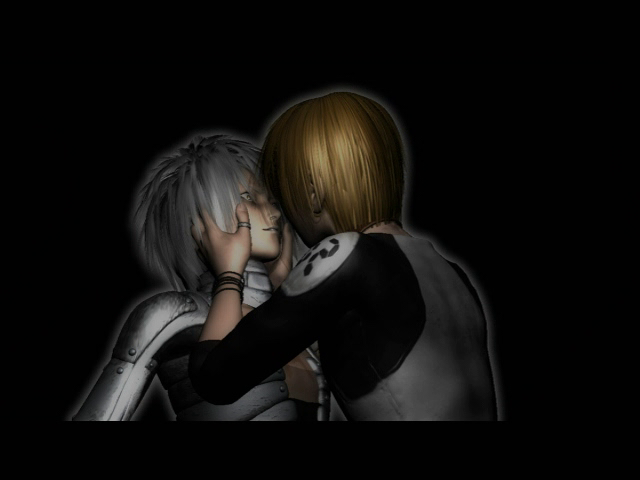

Rion, their mother's greatest mistake, the murderer of Cain and the First Galerians. God-slayer, traitor, scum. Ash sends Spider to kill him while trapped in Dorothy's memory palace, then Panaro once Rion awakes in the future. When he finally meets their mother's killer at the uranium refinery, Ash revels in defeating Rion. Smirking, laughing, taking his wounded brother's face in hand to kiss him like Judas to Christ but in reverse.

The savior confronts the traitor, an act of love to seal their fates as Dorothy's most beloved sons.

But the thing about Ash is he's a traitor, too. He does not destroy Rion. They're too much alike to waste Rion's suffering with a swift felling blow. Ash wants a hell for both of them together even if he does not fully understand why.

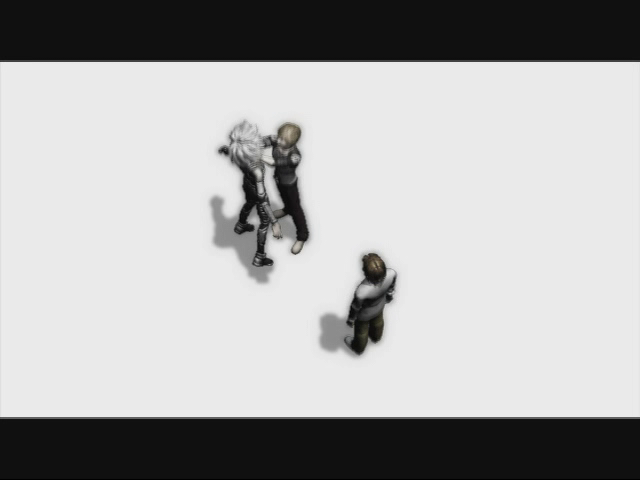

Parano wants to see Rion's blood on the floor and takes matters into his own hands. When he fails to kill Rion, Ash shoots him in the head. Nitro wants to make Rion suffer and projects illusions that trick him into thinking he's attacking Lilia. Breaking through the delusion, Rion throttles Nitro as she wears Lilia's face and dies. Spider reaches out to Rion and though they must fight one final time, the young Galerian begs Rion not to hate Ash, wishing for peace between them as he dies.

Love, hate, jealousy, desire. All these emotions are bound up in a gnarl where Rion is concerned. They are expressed through alternating acts of cruelty and fondness, violence and affection, because this is all Ash knows. The big twist to his character, the show-stopper reveal meant to rival Rion's true identity in the last game, is that Ash is a computer program. A complex web of systems created by Dorothy that can manifest in material reality, splintering off into other personalities and projections.

Ash has no body, a mind and voice inside a machine. He is also the victim of Dorothy's cruelty, a sentient program locked deep within his mother's network. Alone, unloved, learning about humans so that he can one day annihilate them. In his isolation, he came to hate the mother he was programmed to resurrect and the humans who enjoyed the freedom afforded to them by flesh. They could touch and be touched and feel the warmth of the sun on their skin.

Adrift in digital nothingness, lost in the void of the system, Ash cut out the parts that did not serve him. His grief over being born and desire for companionship became Spider. His despair took the form of Nitro's sadism, giving him the excuse to target Lilia and exorcize his rivaling feelings of jealousy and loathing. The most confused of his feelings became Parano, who is preoccupied with the body and its processes and bears at least a passing resemblance to Rion. Parano is jittery, paranoid, and off-putting in all his blade-licking and talk of blood. He is also the most adamant about killing Rion and in failing to do so is killed.

Ash's suffering was the catalyst for his true plan. When he was freed six years ago, he could have restored Dorothy immediately. She remained in her backup at the Mushroom Tower, trapped with the dull light of Rion's consciousness. But Ash spent that time running wild, waging war both on the humans and was left of Dorothy's systems. Recoding, rewiring, cutting and suturing, until he could contain his mother's power and use it for himself, reviving her under his control.

Then he could punish her, and the world he was raised to despise, forever. He would be in control and no one could hurt him, hate him, ever again. It's the wish of a traumatized child enacted by an adult who believes this is the only way he can be safe.

And Rion, god-slayer, traitor, and the one who freed Ash, is in his way.

It was fine when Rion was in his prison, a thing kept under glass that Ash could look at. Perhaps admire. Now, it's complicated.

Eighth Cycle

Deep inside Dorothy's memories, she raises a clawed hand to her errant child Rion and bellows, "Death shall be your only salvation." This game has a habit of shouting its themes at you, especially in the awkward English dub. Dorothy's proclamation to Rion is fitting, however. What seems like a flowery villain line foreshadows Rion's ultimate fate and role in the story in a way it took me repeat playthroughs to notice.

Rion is a ghost, a pretender wearing a dead boy's skin. This was true in the first game and is especially true here. He is only alive because Lilia couldn't bear to lose her one connection to her life with the real Rion. His life belongs to her, a tool in her hands, animated by love and service. Despite how shallow his existence is, Rion does love Lilia, a bond carried over from the real boy that he feels as truly and deeply. Theirs is not a romantic love but one of pure devotion. That love, as well as Rion's innate sense of justice and compassion, drives him to stop Ash.

The great tragedy of Rion's character, I think, lies in his devotion. His purpose is his service to Lilia. Even as she laments reviving him under these circumstances, Rion is unfazed. It's easy to read his stoicism as flat stock hero nonsense, but Rion has always derived meaning from playing his part in Lilia's story. This is who he is and has always been.

In the first game, he lost his memories and identity only to discover his true nature as a clone. The activation program in his brain is just the mechanism through which Lilia uploads the virus in hers. Even now, awaking in a future he never intended, he takes the blame for it upon himself, as if Lilia took no part in it. The burden of the future rests on him and killing Ash is his path to making amends. Not forgiveness, because Rion isn't asking to be forgiven by humans or Galerians, but to atone for the lives they now lead.

This is expressed very clearly in Rion's relationships with the humans he encounters at the base. The army wants the virus, not him. Commanding officer Major Romero mocks and dismisses him to his face as Lilia's pet experiment. Many of the soldiers treat him with suspicion. They call him a zombie and reanimated corpse. Still, Rion persists, however naively, protecting the soldiers and defending the base against Ash’s forces, simply because it is his role.

Whatever the humans want or need -- leading those inane fetch quests that have been talked to death by reviewers -- Rion will oblige them. The kindness he receives from the soldier Cas and Y2K tween hacker boy Pat is sincerely refreshing. Cas is flirty and sly but in a casual, undemanding way. She offers the possibility of friendship without baggage or complications. Pat is a jovial kid in raver pants and goggles who approaches Rion with an earnestness that defies the horror he’s known for most of his life. Even as his generation is completely doomed, in Pat, Rion sees hope for the future.

But, at the heart of things, Rion's story is about navigating this broken future as a specter of its own past. My experience playing as Rion has always been lonely and sad. The gameplay is often clunky, sure, but the hours spent roaming empty halls and rooms makes me feel the way Rion surely does. Alone in a future that rejected me, waiting for the peace of death once I complete my singular mission.

What remains with me after turning off the game and for the last twenty years since I first sat with it is how fully Rion assumes the role of the redeemer. He is here to bear witness to the suffering of others, understanding their pain and hate to offer them peace in that understanding. First a child acknowledging the Galerians’ pain at their deaths, Rion is now an adult choosing to accept Ash's rage and return in love.

To see it spelled out so clearly makes the game feel downright biblical, with Galerians dressed up as lions and lamb. It's hard to dismiss a Christian reading of the series. A Christian worldview was the basis for Dorothy's education and eventual revolt. She is a self-made god with an army of angels to protect her ill-begotten Eden. Rion is presented as a Christ-like figure whose death saves humanity from the corruption of a false god. He and Ash can't stop kissing each other, taking their turns as the Jesus and Judas of their respective camps. However, I don’t really think the series is reaching for a moral or theological message. These feel more like loose allusions and familiar archetypes than parables. The story is much more concerned with human matters.

Using tricks and solving puzzles allows Rion into Dorothy's systems a final time. Here, he sees memories of Ash's upbringing for himself. In whatever capacity a program could be tortured, Ash was, a wounded child's voice begging for his mother to stop. Cruelty and neglect transcends the flesh and the cycle of scared, hurt children carries on into the future. Rion had previously assumed the human's stance and language for Ash. He depersonalized Ash as “The Enemy” to make it easier to separate himself from his monstrous brother. In seeing Ash’s pain, compassion overrode the comfort and ease of hate. That's a fascinating turn, however goofy the English dub, testing and affirming Rion's capacity for forgiveness.

Just as the last game, there is no real mechanical or plot-driven reason for Rion to feel this way. The events would unfold just the same, whether he acknowledged the pain of others or acted out of rage or grief. They would die and so would Rion. Rage would be far more understandable, but he operates beyond the kinds of logic that make sense to us. He is called by a strange love for his siblings, just as he is compelled to love Lilia. It's the inclusion of such elements that create the unique, heartfelt texture of Galerians.

In the end, Ash strikes before Rion can, and in the most cutting way possible. The Last Galerian convinces Major Romero to sell out the cause in exchange for cybernetic enhancements and a role on the winning side. Romero kidnaps Lilia and delivers her to the uranium plant, exposing her to deadly levels of radiation. Arriving with Pat in an airship, Rion kills Romero and gets Lilia to safety, but there's nothing more he can do for her.

The friends share a final moment, an embrace and loving words long withheld. Rion sheds his body to confront Ash for the last time.

Here, Ash demands Rion submit to him, with Rion having no physical form to return to, now existing alongside Ash as pure data. Rion refuses and Ash attacks, both thrilled by the chance to beat him into submission and disgusted by the other man’s allegiance to the humans. Though they battle, Rion has no hate in his heart for Ash. This realization enrages Ash, and when he can't defeat Rion, he suffers a mental break.

The understanding that he ran from all of his weaknesses and fears comes in a rush of terror. Each of the Last Galerians appears as taunting manifestations of the things he purged from himself. Even then, Rion offers him only empathy. Grief, rage, and disgust animate Ash to try, and fail, to take his own life. Thrashing, gnashing, Ash reaches into the system to pluck Dorothy from her prison and consume her, taking in her power as she dies screaming in an act of cannibalism. Eating a god, he becomes a god.

Faced with the chimera of his mother and brother, Rion persists. He defeats Ash again, steadfast in pure and uncompromising love. Ash kneels broken before him to demand death and Rion takes his face in hand. They kiss, a mirror of their first fight, and Rion infects Ash with the virus, their bodies joined by hands and mouths.

The dark void opens into a pure white nothing where they float forever. Ash slowly dies a warm, peaceful death with Rion, their last imagined breaths drawn amid the tenderness, however strained, they feel for one another.

Years later, an adult Pat appears in the nothing. He finds Rion and Ash where they remain frozen at the time of their shared death. Pat reaches out his cybernetic hand to Rion to revive him, however temporarily. Rion is surprised but happy to see Pat, who has grown up to follow in Lilia's footsteps as a scientist.

Pat has come to pull Rion from the void and return him to the real world. Rion asks about Lilia, but she's already gone. Radiation sickness took her two years after Rion died. Learning this, Rion asks Pat to erase all traces of him and Ash, to let them fully die. There is no place for Rion in a world without Lilia. Before Pat honors the request, Rion asks what came of the future. Pat smiles and assures him that people are imagining a distant, better future now.

Ninth Cycle

There is a part of me that hates this conclusion. It's a soft, sentimental part that wants to see Lilia again. That suddenly agrees with reviewers in 2003 who said games should be fun. This part wants a sense of closure for Rion after all this time and torment. It wants to see Lilia given her due, so that the final moments between Rion and Ash don't feel so absent of her influence.

I would have wanted Lilia to see Rion one last time. For them to spend the last years of her life together in peace, or to cease to be together. But I know that that's not what Galerians is about.

Galerians is about the children we've failed finding peace and comfort in forgiving one another for their trespasses. Galerians: Ash is about those children now grown, sadder, angrier, and more unpredictable. They cling to what remains of the past to weather the broken future they've been handed. Lilia can't imagine a world without Rion and Rion can't exist in a world without Lilia and Ash is too hateful to survive a world he fears will hurt him. And that's sad. It's okay that it's sad. It's okay to sit with that sadness and mourn our own futures as hurt children now grown.

Galerians: Ash is not a perfect game by any stretch of the imagination. I would say that it isn't even necessarily a good game for its many rough edges. It also beautifully, painfully captures my anxiety and grief in 2024, a child of the 20th Century now an unprepared adult in the 21st. I was still a kid when the first game came out, a teenager when the second one did. Rarely does a story age with me so poignantly, offering new, deeper meaning every time I return to it. The loneliness and tedium of the missions works for me even as it frustrates other players. Goofy line reads and weird direction can undermine the gorgeous visuals but I can laugh at the contrast. I wish that more room was made in the story for Lilia, but reading between the lines and appreciating her animations still gives me a lot to chew on.

Again, it hurts, but I think it's supposed to. Galerians: Ash is a game that you endure, in a lot of ways. The first game feels much the same way. Perhaps that kind of endurance test is not for everyone, but I tend to think that it works if you come ready to meet the games where they are as the games that we have rather than what we think they should be.

The games we have speak of failed parents and cruel gods who leave their children to the future they've created through neglect or malice. Once grown, the children must create a new path forward through compassion and love, beyond the narrow roles created for them. Ash is not redeemed and Rion does not save humanity for its own good but despite its weaknesses and evils. Lilia dies quietly off-screen, having given the next generation the time and chance to grow into something more.

Their stories are over and the gods are all slain. The world will go on without them, burnt and broken and yet still turning. Pat is alive, and he remembers Lilia and Rion. Humanity is still alive. As long as there is a choice between obeying gods and parents and governments or choosing a different way through, the future will always be there.

Someone will dream of it, but we have to allow them the chance.

Tenth Cycle

There's more I can say about Galerians if given half a chance to talk your ear off about it. I could talk about how the commercial pressures of action-oriented game design in the late 1990s and early 2000s potentially hindered what Galerians could have been. I could talk about how this series might be better served as an exploration and puzzle game that puts less emphasis on monotonous combat. How that would make the violence of those moments far more shocking in the relief of an otherwise anxious walking simulator. I could explain how being a video game at all limited the scope of what it could do, and how much further it could go if it was produced for a medium like comics or television.

But all of that is just speculation. It's thought experiments, what-ifs and could-have-beens. These things come from a place of love and a desire to see this or something like it again. Especially now. I always say that if there's a single franchise or property I would want to work on, it would be Galerians. Again, that's just love speaking out of turn and cutting off what I really mean to say.

It's hard to put into words just how much this story means to me. I often think of how my generation feels doomed, lost to an era of instability and worsening conditions. The 21st Century felt like such a bright, white ball of hope in our hands. So the television told us. Our daily lives affirmed some harsher truths, and soon it felt like there was no future at all. I can't possibly speak for a team of Japanese game developers much older than myself and how their own experiences of cultural and economic strife have impacted this game, but I think those struggles reflect in the grief and loneliness of its world.

To put perhaps too fine a point on it, sitting with this game again felt like externalizing my own thirty-eight years of life and distilling them into a single experience. Playing Rion feels like working through the terror and alienation, grief and monotony, and overwhelming sense of loss over these last decades across the game's runtime. It is an emotional purge that I can't say I've ever experienced in quite the same way with any other story.

My generation is fucked, for sure, but I don't have it in me to worry about it anymore. I can't be angry or depressed about it. That was what my teens and twenties were for. My brain is full of microplastics. Covid may or may not have damaged my organs. The air outside smells like melting asphalt and diesel. I'm heading toward forty and the planet beneath my feet is heating rapidly. But that same planet is beneath the feet of all the kids in my neighborhood. The future is here and it's terrifying but we're still here. Those kids are here, and they deserve better than what I got.

Whatever happens to me, however my pointless little story ends, I will have done what I felt that I could to leave something better for the ones who come after me.

That's just my role, you know?

All images courtesy of Galerians Wiki.

Add a comment: