I Buried My Love at Toluca Lake

I'm going to make two very normal statements that the non-gamer contingent of my subscribers may not understand. Rest assured, they are very normal.

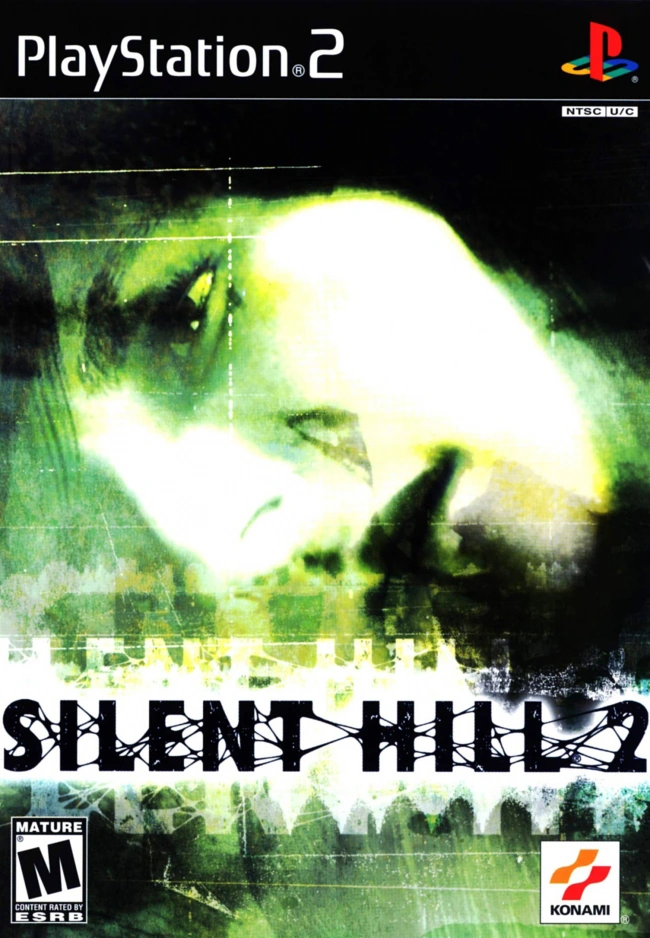

Widely celebrated as a horror masterpiece and a triumph of the medium, Silent Hill 2 is a very good game.

In step with the conflicted reception that it garnered upon release, I didn't like it when I first played it.

Well, to be fair, “played” is a strong word. My relationship to the Silent Hill series was filtered through the lens of the audience rather than the player during my most formative years. The first game came out in 1999, when I was 13. Back then, my younger brother Ian was the family's dedicated gamer. I was the co-pilot, the go-to guy who read the walk-throughs and the cheat guides while he played. A man couldn't read a walk-through and game at the same time. My role was just as important, especially if our friends were over watching Ian play.

Silent Hill is a survival horror game series, originally developed by Team Silent for the Playstation and published by Konami. The first game was released in February 1999 in North America, March in Japan, and July across Europe. For the uninitiated, survival horror means that you collect weapons and supplies, manage your inventory, and solve puzzles to navigate an increasingly hostile environment. Initially conceived to cash in on the 90s horror boom in Japan and, more specifically, Capcom’s wildly successful release Resident Evil, Silent Hill took a dreamier, more abstract route, with an opaque plot and a strange mystery to unravel.

You play as the very unassuming Harry Mason. Rather than a cop or soldier, Harry is a writer and widower who visits the town of Silent Hill with his young daughter Cheryl. He sees a woman in the road and swerves his car to avoid her, crashing it and waking up alone. Harry must survive the town as it is descended upon by monsters and find his missing daughter by any means necessary. The game’s tension comes from your vulnerability, your soft human defenselessness, taking up pipes and handguns to fight back against things that you can't understand.

Playing Silent Hill by watching Ian play was as close as I got to that foggy town. It's a tactile thing for me. The sensation of sitting cross-legged on the itchy carpet under a stolen blue blanket, my fingers poking from the holes singed through by cigarettes. The weight of those printed tomes resting in my lap, my fingertips spit-slick as I rapidly thumbed through them to find the answer for a puzzle or the easiest way to end a boss fight. Kool-Aid-red lips, sunset colors pooling on the floor through the half-opened curtains. Keeping the volume low and speaking under our breath so as not to wake our napping mother. These moments were as much Silent Hill as the monsters that inhabit it.

This was how I became enamored with loving father Harry, determined Brahms cop Cybil Bennett, and the haunted nurse Lisa Garland. I felt fear for the fate of Cheryl, and a profound sense of grief for her true form as Alessa Gillespie, sacrificed by her own mother to the town's dark old god to birth it anew on the earth. The ending, as Cheryl and Alessa became one to be born again as an infant for Harry to raise far away from this town of cultists and abusers, lived rent-free in my 13-year-old brain for many years.

My fondness for and familiarity with these characters carried me to Silent Hill 3, when I finally took the controller for myself. I played as Heather, Harry's now teenage daughter and Cheryl/Alessa reborn. This time I found myself grieving for Harry, slain by the town's cult to push Heather to accept her fate as the vessel for the unborn god. Every wet, fleshy enemy felt like a real threat as I mashed buttons to swing Heather's pipe at them, avoiding the things that grasped and gnawed at her. A teenager myself, one with a strained relationship with my body as well as many skeletons in my family's closet to contend with, Heather's story was easy to relate to and satisfying to see resolve.

Next, I fell head-over-ass in love with Silent Hill 4: The Room, the series’ then-troubled black sheep. I found myself captivated by Henry Townshend's claustrophobic nightmare, waking up locked in his own apartment with no way out. Nodding to Hitchcock, his only connection to the outside world was the windows overlooking his sleepy neighborhood block, as well as the strange hole appearing in his bathroom wall that led him to water-logged prisons and burnt-out hospitals. Of course, he also had the peephole in his chained front door, and the peephole that appeared behind the bookcase that peered inside his neighbor Eileen's bedroom.

Silent Hill 4 was a game made for me. Its gameplay was plodding and punishing, story heavy with ambiguity and unanswered questions about the kind of man I was playing as. Quiet and mumbling, Henry seemed to sleepwalk through the events. He wasn't really affected by much of the death and violence he witnessed, even as he acclimated a little too quickly to the stark voyeurism I was presented with as a player. I was so unsure of how sinister his intentions were as he grew close to Eileen and unraveled his (or rather, his apartment’s) obtuse connection to the larger story of Silent Hill.

So, you would think that Silent Hill 2 would be a game made for me, as well. Detached characters in a horrifying situation navigating dubious gender and sexual politics sounds like my jam.

Actually, I thought it was kind of boring.

I have no shame in admitting that my teenage self (then 15) wasn't the most astute critic. The years between the second and fourth games broadened my tastes a bit, but at the time, I didn't get Silent Hill 2. I mean, I got it the way most people at the time seemed to get it. James Sunderland receives a letter from his dead wife Mary telling him to meet her in their “special place,” the quiet foggy town where they vacationed before her illness. There, the spacey, not-quite-there James meets a cast of other decidedly Lynchian characters: the skittish and disorienting Angela, the off-putting and vaguely sinister Eddie, the smart-mouthed little girl Laura, and the seductive Maria, a beautiful woman who wears Mary’s face. The performances are stilted and the dialogue is disjointed and dreamlike. Characters talk around things, speaking past each other in broken conversations that don't quite link together at the moment but make more sense as you move through your shifting, dissolving surroundings.

In his travels, James is stalked by Pyramid Head. (Sorry, I know his official title according to designer Masahiro Ito is Red Pyramid Thing, but he's just Pyramid Head.) The franchise mascot is little more than a strange, lumbering man with gloved hands and a bloodied butcher’s smock. But it’s his impossibly large red helmet, dragging an impossibly large blade behind him, that gives this creature his menace. Silent, predatory, and hiding around corners and in empty apartments, hips jutting maliciously forward as he walks. There, James’ stalker attacks, subdues, and dominates (in whatever way you want to take that) the bound figures and disfigured bodies that roam the streets of Silent Hill. This, while James watches from inside a closet, which feels very weird and bad especially when you're a teenager.

Outrunning monsters in his search for Mary, James inevitably discovers the truth about her death, seeming undeath, and the nature of what Pyramid Head is to him.

And, you know. I thought it was...fine. It was okay. Not great, but, whatever.

At the time, I took James at his word. Blank-faced and guileless, he performed grief for his poor dead wife who now called him to the town with these other lost souls. James seemed bumbling and confused, a man thoroughly lost and doing his best. An innocent man. If not innocent, then at least certain in the virtue he assured everyone else he possessed. James would never kill a human, never kill himself, never kill anyone. To his credit, or rather to the credit of his English voice performer Guy Cihi, James seemed genuinely empathetic toward the supporting cast. He appeared concerned about their safety in this hellish town and the harm that could befall them, whether by a monster or their own hand.

However, James begins to contradict himself as the story progresses. Eddie’s wild-eyed rambling as he waves his gun and relishes in killing gives James someone to compare himself favorably to. Angela's grief and rage at her abuse and abusers let James play hero. He limply attempts to keep her from hurting herself with her tightly-clutched knife while insisting that he would never, ever kill himself, a staggeringly uncaring thing to say to a woman in crisis. Laura, Mary’s young friend from her hospital stay and the only living connection to her, is subjected to James’ random outbursts of anger. Whenever the child’s close friendship with Mary runs in contradiction to his version of events, he shouts at her, scaring Laura, then tries to walk it back to keep her on his side.

The doppelganger Maria draws James to her with her dominating presence, providing the direction he lacks. Maria exists in a nebulous space between poles, personalities, and states of matter. She dies and is resurrected again and again, shifting between the sweet-natured teasing of the more modest Mary and the flirtatious confidence of Maria. In the moments between her cyclical deaths, Maria controls the scenes an otherwise passive James stumbles through, but also performs Mary’s need for comfort and fear of death. Her spells of fatigue and coughing make her a liability when avoiding stalking monsters. She dies, and James can't protect her. She is vulnerable beyond the threat of physical harm, but James can't seem to fully recognize that. Maria is desirable, but confusing. Inconsistent. Inconvenient.

This? All of this? I took it at face value. James is the protagonist. The evidence of who James is has always been there, but I was trained to take his word for it. Like Harry, he's an everyman faced with incomprehensible horrors. He's the grieving widower. He's looking for his wife. Yes, he’s following around her doppelganger, but he's alone and in pain. Of course, he's fascinated by Maria.

Of course, James loves Mary.

Of course, he took a pillow and put it over her face.

Of course, he can't remember what happened.

Of course, he put an end to Mary's suffering.

Of course, he can't bear to accept what he's done.

Of course.

That's not what the game is saying, I don't think. There's a lot in it to tease out after repeated play throughs, a lot of talk and think about. But that's the flat reading I took from it. This is the Jacob's Ladder fanfic game, I thought, where a man kills his terminally ill wife to put her out of her misery and then punishes himself for the act. The sensual shapes of the malformed nurses, the monsters made of legs or mouths or bound arms, all speak to James’ understandable sexual frustration at the loss of intimacy with Mary before her death. He creates Pyramid Head to judge and punish him for the crimes he won't, or can't, accept. Once he does accept what he's done, he can move on.

There are different endings of the game that assure me of this fact. The “Leave” ending sees James escaping Silent Hill with Laura, like Harry and Heather before them, having put all the horrors behind him to begin anew. The “Maria” ending sees James defeating Mary's angry spirit, overcoming his guilt, and leaving with Maria, even as she begins coughing in the early stages of Mary’s terminal illness.

For years to come, that was my reading. James did something bad and was punished for it. Is it a teenager's lack of critical thinking? A bit of the old internalized misogyny? Sure. I cop to that.

But I think beyond even that, I simply lacked the lived experiences needed to grasp the thoroughly adult ideas at play in Silent Hill 2. Heather made sense to me as a teenager. She was surly and grieving and living alongside adults that could, and would, and did, hurt her. Henry later made sense to me, a victim of his circumstances but also a participant in very creepy behavior that I could easily recognize. The direct or indirect predation and exploitation of women and girls in those games rang true to me on a very visceral level. Heather is forced into the adult world of sex, sexuality, and childbirth against her will. Eileen is stalked, observed, and made into an object or vessel, less a person and more a thing.

Everything that happened to Alessa? Abused by her mother and exploited by the entire town? Forced to serve the cultists' machinations through the sacrifice of her body and autonomy before she can even grasp what's happening to her? I got it like a hammer in the teeth.

(Oh, and Harry is just a good dad. Yes, he's made far more complicated and messy through Heather's story, but he's still a good man who's doing his best in an impossible situation. RIP, the girl dad king.)

Now that I'm an adult, in my late 30s, with a lifetime of experiences to color what I see in James and the inner life splattered across the streets of Silent Hill, I feel very differently about him. Just as I feel a little less attached to Heather and Eileen, I find myself fonder and fonder of Angela, Maria, Laura, and -- well. Maybe I'm not fond of Eddie, per se, but I can certainly appreciate his role in the story more than I did before.

There's really no inciting incident for this reexamination, no one moment to point to. I certainly have a distant relationship with Silent Hill these days. The troubled release of the interactive web series Silent Hill: Ascension didn't even reach me until I sought out Twitch livestreams to watch the calamity for myself a few weeks later. Silent Hill: The Short Message didn't interest me upon its announcement and release, given the way it seemed to take the best elements of Hideo Kojima’s PT and make them worse. (And PT is a whole other can of worms that nobody has time to address right now, let me assure you.) I definitely have no feelings about Bloober Team’s upcoming Silent Hill 2 remake. Sure, it looks nice and will probably be easier to play with modern hardware and design conventions, but I don't have a console to play it on. Honestly, I can't imagine wanting to, either.

So, what then? What is the point of this essay if I’m not trying to tether myself to some topical bit of Silent Hill news? The answer is, I don't know, really. I’ve just been spending a lot of time with Silent Hill 2 over the last few months, and it's earned a new fondness from me for all the ways that it is truly wretched to experience.

To me, James Sunderland is a monster. Perhaps the monster, one of the all-time greats. He may not look like one, but he is a familiar thing to watch move across the screen. A dead behind the eyes thing, a say-the-right-thing-when-you-need-to-hear-it kind of thing. It's the banal monstrosity of a coworker, a friend's boyfriend. Maybe a brother. Maybe a father. Maybe your husband. He may not have always been a monster. He may have loved her as much as he claims to. But when Mary’s body failed her, James resented her for ruining his life.

He was given the choice to be with his wife through the most painful and arduous experience of their lives together. He chose a perverse self-preservation instead. His life simply mattered more.

To me, with hindsight on my side, James is wretched because we're -- me, I’m -- conditioned to empathize with him. He's the brave husband of a very sick woman, after all. Once beautiful yet modest, the kind of woman who kept a nice home and made for good company, Mary was made ugly and inconvenient by her disease. She is no longer desirable to James as her disease consumes her. James stops visiting her at the hospital. Mary knows this. She mourns this, feeling ugly and burdensome in her condition. By her own admission, she lashes out in the early days after her diagnosis, growing angry about her disease. She feels that she's driven James away, hurting him and robbing him of his freedom. In one of James’ (seemingly rare) hospital visits, she lashes out at him for bringing flowers when she feels so ugly and undeserving.

We know this, because we hear these words play out as James moves down a long, dim hallway toward his final confrontation with Pyramid Head and Maria. These sentiments are also in the letter Mary wrote before she died. The one that led James to Silent Hill in the first place. The one he claimed to receive three years after her death, but was revealed to always have in his possession yet never read in full. These were Mary’s grief-stricken thoughts at the end of her life, and James didn't even read them. Then he would have to face what he did to her, even as she did everything she could to make it easier for him.

I can absolutely see a scathing reading of Mary’s characterization through the lenses of disability and end-of-life advocacy. A terminally ill woman voicing such self-loathing and guilt stings quite a lot to hear, especially two decades removed and across an ocean of cultural context. But I can also understand why a woman would feel ugly in her sickness. Angry at her sickness. She's lonely and restless in her partner's prolonged absence, blaming herself when she can't be what her partner wants and needs anymore. This is her life stolen by disease, and she fears dying and pain. I can't blame her for wanting better than this, and focusing on someone, something, outside of her own failing body. For blaming her disease for what James does rather than James for responding the way he does to her illness. She wants to be loved. She wants pleasure. She wants to be desired. And, yes, if she can't get that for herself, she at least wants James to be as happy without her as she was with him.

It's sad, but…Mary was a woman in love who had her life cut short. In her eyes, James was only ever good to her before her sickness and they were happy in their marriage. Now her illness has cost her everything. I can see why she feels what she feels.

If I were dying, I can't say I would never, could never, feel the same way. I know what it's like to anchor your sense of self and worth to someone else's perception of you, and I know what it's like to ache for love. To make yourself perfect in order to be loved, and to dissolve when you can't be perfect enough to make anyone love you.

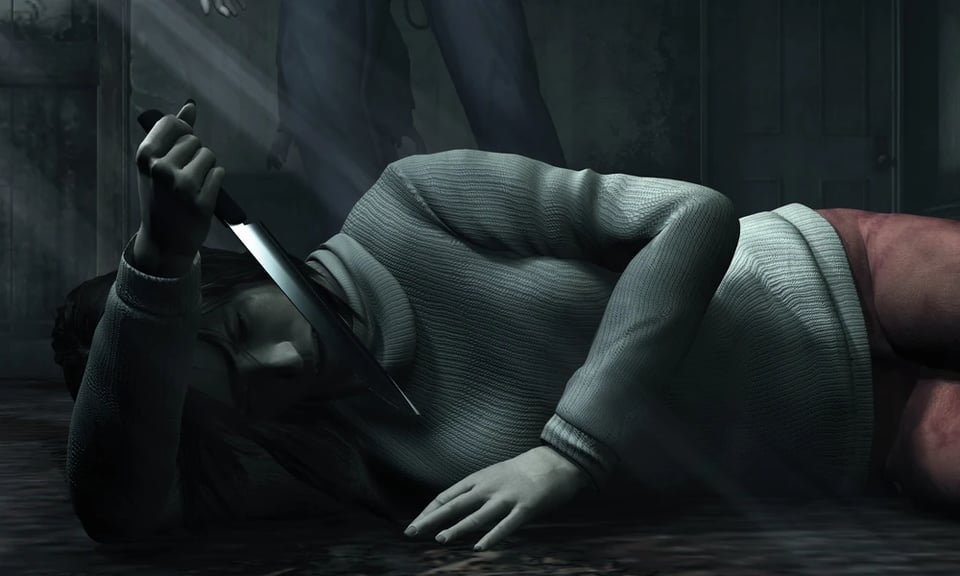

Yet James stood over Mary's bed during her last visit home, kissed her on the head, and put a pillow over her face. Creeping over her like a stalking monster, a thing now chasing him in dark corridors and empty streets.

Before, I saw James as a flawed man. Today, I find James a compellingly nasty thing to watch unravel. He loved Mary when it was easy and comfortable to do. He stopped seeing her at the hospital, which even Laura knows. He felt trapped by her disease even when he had already stopped supporting her, which even Angela knows. He hated when she lashed out at him, and couldn't deal with her fear and grief when she begged him for comfort. Bringing your dying wife flowers when you can't even look her in the eye isn't noble. But James wants to believe he did everything he could.

He wants you to believe he did everything for her.

We know this, because this is what Maria says to him during their final confrontation at the end of the game, when he must defeat her. That she can be whatever he wants her to be, and she won't leave him, and won't yell at him or make him feel bad. She can be perfect in the way Mary could never be.

And this is why James’ story means the most to me now.

I know the looks James got when he said his wife was sick. I know how people shook their heads and pursed their lips to make sympathetic noises. My partner Melissa is chronically ill. She isn't terminally ill like Mary, but she's never going to get better. Her illness has made her disabled, and her doctors manage her illness by keeping it from progressing for as long as they can.

While I have my own health issues, some more chronic than others, I am the brave one who stood by my partner in her illness. People tell me I’m strong. They tell me it must be so hard for me. That I must have sacrificed so much in being with her.

Never mind that Melissa is…fine? Things are hard, but she's fine. We're fine. We've had to make adjustments. I have to do all the things she can't do anymore, and we have to live much more slowly than most able-bodied people our age. When things inevitably get harder, and she is more limited in what she's able to do, we will make more accommodations. Because that's what you do when you love someone.

You make it work.

But that's strange to people. You know? They don't admit it, but it's something alien to them. It's brave. It's laudable. It's so great that I can do that.

Even if…

You know.

It must be so hard for me.

The thing is, I can see why you might take James at face value. I can see why I did. He says he misses his wife. He says he came to Silent Hill to find her. He seems like a good man who was pushed to a desperate choice and chose to put his suffering wife out of her misery.

It's brave to stay with a sick person.

And it's brave to put them down.

You did what you had to you.

Even when defeating Maria and facing Mary one final time on her deathbed, James’ first instinct is to tell the lie. He loved her and couldn't watch her suffer anymore. After a moment, he falters and tells the truth.

He hated her for ruining his life.

It makes me wonder what he came to Silent Hill for. To find her alive, or to kill her again?

The other thing about James is, I know him in other ways, too. I know how men become him, and how we make excuses for them. I have been the one living with a sick, disabled, and eventually dying family member. Standing beside my grandmother's bed day after day, helping my mother clothe, feed, bathe, and change her. For years, it was like this. For years, I watched men in my family drift away. They ignored my grandmother when they walked through her bedroom, or scurried away when she tried to speak slurred words after her multiple strokes.

It was just too hard for them, my mother said. They just loved your grandmother too much to see her suffer, my mother said. I just had to understand their feelings.

And, yeah. I got it. It wasn't easy for us to watch her suffer. Taking care of her around work and school. Watching her weaken and lose the light behind her eyes.

And when my grandmother eventually died, I had to listen to these men speak, lips quivering, eyes red with tears, about how they took care of her. How close they were to her in her final days. In my own grief and conflicted feelings, I was told to tiptoe around theirs. I treaded lightly so they never found out how hard it was at the end of my grandmother's life. That ugly knowledge was for me to keep alive inside me, I was told, because it was simply too much for them. The ravages of disease and disability were not made for the men to know about.

Revisiting Silent Hill 2 as an adult is a very different experience. It's become the game I enjoy the most out of the series, and an odd source of comfort. In watching James warp the town into a reflection of his psyche, I watch how his lie twists every person there. Eddie is the ugly, selfish murderer that James pretends he isn't, and Laura is the child he and Mary could have had if she hadn't gotten sick. Maria is born from his wish to possess a beautiful woman rather than be saddled with a sickly housewife. Angela flits between disoriented despair and fiery rage to spit accusations of guilt at James, as if fleetingly possessed by Mary before coming out of her fever dream.

Like the monsters with their long legs and bound forms, the women around James buckle under the strain of his presence. He can pretend to be kind to Angela or concerned about Maria, yet Angela is a broken girl he can rescue, Maria a thing to own. But, given how brave James is, how noble he is in his grief, we will fall for the lie until James too is confronted by his crimes.

These are things that I struggle with as the partner to a disabled person, and as a caregiver to a dying woman in my younger days. I fear that I'm not adequately supporting Melissa, or that I can make her feel like a burden. I never want her to feel like I would be better off without her. I never want people to see me as brave or strong for lowering myself to being with a sick and disabled person. They aren't constant fears, of course, but they itch and scratch in the back of my mind in weaker moments.

I never want Melissa to ever feel like Mary.

I never want to tell lies at her funeral.

Silent Hill 2 is my favorite game in the series right now. It's like pulling something ugly out of myself each time I sit with it. James isn't a blank protagonist to project myself onto. He's a loathsome character, a man rotten down to his core, such that he remakes Silent Hill in his wretched image. James is someone I will never be, but someone society would allow me to be. James is punished the way many of those who neglect, abuse, or kill the sick or disabled people in their lives often aren't. Not by the law, but by his victim. It's…cathartic, in a way that other people may not understand. Perhaps not in terms of gameplay, which take complex themes of guilt and acceptance and turn them into admittedly goofy fights against twin Pyramid Heads and an evil bondage nun version of Maria for some reason.

But if you know, you know.

My favorite version of the story, the “In Water” ending, is the way I believe the story should be told. James sits by Mary's bed one last time and tells his lies and truths. She confronts him about what he did to her and he accepts it. Holding her hand, he watches her pass without violence this time, then picks up her body to leave with her. James’ narration plays over a black screen as he realizes he cannot be without her, tires screeching before the television fills with water. For someone who has spent the story positioning his life above everyone else's, asserting that he would never stoop so low as to kill himself, it feels right for James to drive his car into the lake.

But, all of that said…I still like James. He still draws an empathetic reaction from me in his vocal performance and animation. There's something so compelling about his defeat and despair, even when we know what he's done. During his final scene with Angela on the burning stairs, when he tries once more to keep her from killing herself, I believe his sincerity. The drive to save Angela may very well be self-serving, but it's also the compassionate response to someone so utterly consumed by her suffering. I believe James cares. Not because it fixes or absolves him, but because Angela’s determination to end her life is unconcerned with him. What he wants doesn't matter because this isn't a choice he can make for another person. He is left only with the discomfort of knowing that in choosing for someone else, he is always wrong.

Mary is allowed to be complex in her life and death, dealing with grief and fear and rage. And so too is James complex in his journey across Silent Hill. I understand how difficult it is to watch a loved one lash out at you as they slowly die. I understand wanting to look away. To run away. To wash your hands of the whole ugly mess. To want to fix your past mistakes by making the inverse choice, as if you can trade one life for another. To think all of this is a matter of balancing scales and measuring souls against feathers or stones.

What I don't understand is succumbing to those feelings, and taking someone's life for such selfish reasons. Mary was already dying, and James killed her out of spite. That is so vile to me, so violating. It makes me sick to think about, even as I find myself fascinated by the awful things he does.

That's why I love Silent Hill 2 the most right now. Yes, for Maria and Angela and Laura. Yes, for the stomach-turning creature designs and nightmarish environments. Most of all, I want to sit with the monster of James Sunderland and feel the daylight between us, even as those ugly thoughts and feelings bleed across the space.

-

You did an excellent job stating your argument for how monstrous James really is. It's interesting that Silent Hill 2 manages to feel so different compared to the other Team Silent games, entirely from Guy's performance and James's mentality combining to make him such a miserable voice to be shackled to. By comparison, both Harry and Heather can come across so goofy in their reactions to stuff around town in Silent Hill. The idea that James is incapable of giving himself even a moment of levity reinforced what you say about how-dare i say it- Self Righteous he is about his own life.

For James, life revolved around Mary- But Mary, in his eyes, revolved around him.

Add a comment: