Finding God in Miami and Other Stories

I had a religious experience once.

Well, I guess that's kind of overselling it. It wasn't in a church or a temple because I don't really believe in that sort of thing. I didn't come up with faith. Faith existed on the margins of my life as a sort of vague, shapeless idea. As an infant, I was baptized and ushered into the Christian religion the way all children around were or eventually are. I know this because I was told as much despite the lack of family photos, but that was the extent of my relationship with Christ for much of my life.

Religion was present in the home as objects rather than beliefs. My broadly secular parents had an old black bible stashed away on a shelf somewhere, its spine cracked and pages stained. Nobody ever read it. I can't say that I read it so much as thumbed through it as a child, amazed by its size on the shelf and taking it down to admire. Each of us three kids eventually had our own small white bibles, handed to us one Easter morning. The bibles were crisp and clean with textured covers and stamped letters pushed down into the cloth. They were probably purchased at a dollar or discount store, now that I think about the quality of the book.

Receiving the bible seemed more like an obligation rather than a specific rite of passage. It felt important at the time, given the weight of the book in my small hands and my mother's somber reasoning: “You should have your own bible.” My grandmother, my mother's mother, was religious. My mother wasn't demonstrably religious or faithful, nor was my father. Having a bible felt like a way to appease my grandmother, or at least pay lip service to faith. If either of my parents felt strongly about God one way or another, I didn't know about it.

Besides admiring the family's untouched bible, I would sit dutifully with my grandmother during her visits to look on as she read hers. It was a big black book that appeared pristine to me despite its age. My grandmother was careful not to spill her tea on it or get the crumbs from her morning muffin or biscuit on the pages. She spoke plainly of God and Christ as if they were in the room with us. As if I could touch them. I took these gentle sermons at face value and nodded my head in agreement as she explained the suffering and sacrifice of Jesus Christ as our Lord and Savior. These are not teachings I remember very well, but I did take one pearl of wisdom to keep for myself:

“God doesn't live in a church. Any building can become a church if you accept Jesus. As long as you accept Jesus, every room is a church.”

That felt very comforting to me. It felt very true. What a tantalizing idea, to make all the world monuments to God. Every room, an altar, every corner a holy place. The sweetness of it was made all the more alluring once I understood what a church could really be. The one time I attended a physical place of worship regularly as a child, I was taken to my family's non-denominational Christian church. It was during the summer when my mother moved us kids to Missouri on the threat of divorcing my father. I wish she had – every day, to this day, do I wish she had – but that's another matter altogether.

We just started showing up to church like that was the way it always was. The adults in town, most of whom were my great aunts and uncles and second cousins, seemed pleased. The children were anything but pleased or pleasant, but it was a small town and we were strangers to them. It didn't help that I had no filter and few social skills as a homeschooled child, and didn't take well to being pushed around.

Sitting in church, I found it all a bit…strange. It didn't feel like a warm, loving space. This had been my family's church for generations but it didn't look the way my grandmother described it. It certainly never felt safe, with all these eyes on me and the whispering that went on in the parking lot after service. Everyone knew everyone's business

They clucked their tongues and shook their heads and spoke in hushed tones about who was or wasn't walking a godly path.

I can't say that I found any peace in that building. God didn't seem to speak to me at the time, either. I listened at my grandmother's behest, but nothing came. The pastor gave his little speeches, and I felt nothing. If God was in every room, and every room could be a church if you allowed it to be, why wasn't He here? If I was there to listen, why didn't He speak?

One day I took the silence for an answer and never thought of churches again.

As an adult, I regularly oscillate between the two poles of Atheist and Agnostic. I don't really feel any which way about faith. Confirming or denying the existence of a god/the gods feels a bit above my paygrade. While I can't say I've found him/them, I certainly won't shout down somebody who says they have. I envy that certainty, that steadfastness, the peace found in faith.

But anyway.

This isn't really about faith.

When I say I once had a religious experience, I mean it in that very trite, God Is a DJ by Faithless kind of way. Even that feels a bit silly to claim, you know? I'm not the kind of person who ever found faith in clubs. I did my time bar-crawling, sure. My twenties were spent working in restaurants in a town where everyone was an alcoholic and so everyone was friends with the bartender. My friend group was too busy drinking through their paychecks to go dancing. The one or two times that I find myself goaded into dancing by a fair weather friend, well.

What I said before about being a homeschooled kid with no social skills? You can imagine the results for yourself.

When I did have my little religious experience, it was March of 2024. Me and my girlfriend Melissa made the journey to Miami and the local legend of a venue, Club Space. We didn't make it to Space itself, of course, with its beautiful rooftop terrace overlooking the city. I'm about as likely to be seen in a club as I am in a church, historically speaking, but the times are changing.

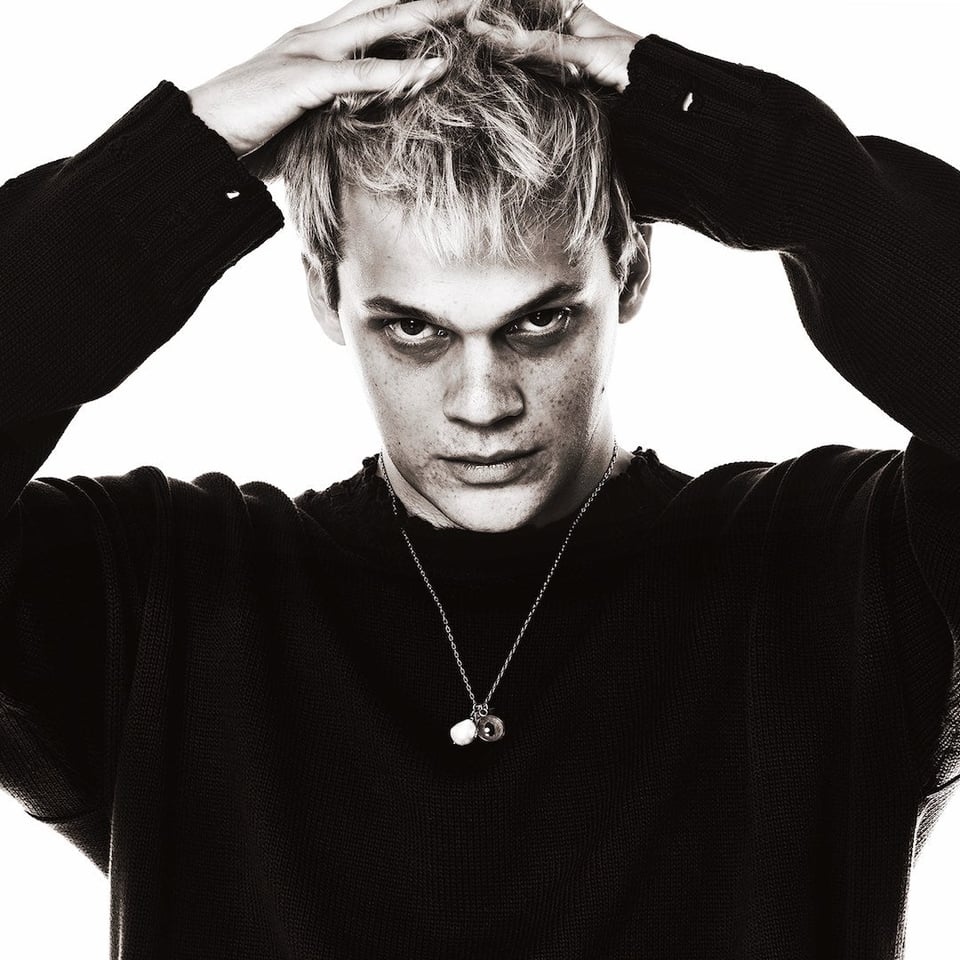

The show we were seeing was scheduled for Ground, the cute but relatively humble first floor bar about the size of my 500 square foot apartment. There was a little stage and a little bar, and things were stripped pretty bare for the occasion, save a few pink-lit hallways and spots clearly telegraphed to take photos in. Everything about it screamed “2017 bar bathroom selfies,” because bar bathroom selfies are something I do know a bit about. It was fitting, and also a little funny, as we were going to see George Clanton.

You either know George Clanton or you don't. You either love him or he annoys the piss out of you. There's really only two speeds with the electronic artist, singer songwriter, and label owner of 100% Electrionica. Clanton is easily one of my favorite musicians working today. His most recent albums have a dreamy 90s alternative rock vibe laid over the processed sounds. The vocals are soft and fuzzy, giving a faraway feel to sparse lyrics that are often weary, self-loathing, and profoundly familiar in emotional content.

Clanton walks the fine line of making somber melancholy in the form of upbeat pop and electronic music. It's the kind of music that beautifully renders the sensation of knowing very well that you're the problem in your own life, the immutable obstacle in your path, without tipping over into the sticky trap of self-pity. Or worse yet, hand-waving positivity. In that way, Clanton's work feels timeless and prescient. Tracks like I Been Young and Justify Your Life could have been recorded in 1998 or 2013 or ten minutes ago. Monster and Make It Forever feel like they've always existed and I've always listened to them, because they're just always there. It's like hearing your bleakest, shittiest moments sung back to you by a guy who very clearly gets it.

Yeah, you're here to dance and party and chill and groove, but you're always acutely aware that you aren't running from anything. You're dancing through the pain. The pain is with you in the club, or the car while you drive around, or the kitchen while you listen to music and cook or clean.

It's cathartic, the way being seen and understood, even by a stranger – maybe especially by a stranger – is cathartic. You can become anonymous by listening to music. This isn't your deeply felt loss and disillusionment but Clanton's. Or maybe it is so intensely, impossibly intimate in its depiction of that quiet grief for who you could have been that it can't be about anyone else but you.

For all of the moving elements of Clanton's body of work, he is also kind of a sentient shit post. I'm aware that makes him something of an acquired taste. With messy bleached hair, dark sunglasses, and a dismissive air about him, Clanton appears to speak primarily in tangents. He's constructed a glib, weird, and often put upon persona that in one breath takes the piss out of himself and the next demands total allegiance to his incredible talent. There are a lot of people online who want him to be a villain. It's probably pretty easy to be one when people are expecting, even demanding, as much of you.

It frequently confuses interviewers and those not in on the bit. The bits include getting mad at the fans who frequently steal his shirt at shows, selling pieces cut from his own clothes as merchandise to such fans, claims of fans dosing him with LSD against his knowledge, threatening to call the authorities on his fans, publicly reading posts from his subreddit with an AI Peter Griffin voice, having homoerotic tension with his male fans, and posting unflattering selfies on Instagram.

He also posts cat photos, which are always nice, but he can be a tough pill to swallow.

When Clanton announced the tour dates for Florida, Melissa got our tickets immediately. She had his 2018 album Slide on repeat for years at this point. It accompanied us on coastal drives and while cleaning the house on Saturday afternoons, doctor's appointments and medical procedures. On the day of, we made the drive to the famous Miami club district, as two elderly millennials ravaged by time and hoping to get home at a decent hour. We got lost three times trying to find parking. We got lost again on foot trying to find the place amid the usual danger of Miami drivers, whether by car, bike, or delivery truck.

This crowd was exactly what you would expect if you know Clanton's music. Dudes in bucket hats and obscure vaporwave t-shirts. Shaggy haircuts and questionable facial hair choices. A lot of confused girlfriends who came along, not sure what to expect. Goths. Nerds. A few people seemed to buy tickets at the door to get into the bar and had no idea what was going on. When Clanton took the stage, alone with a sound board and an electric guitar, wearing sunglasses in a dark room, he chided us. He talked back to the rowdy crowd and the guy in the bucket hat who kept interrupting him to scream “I love you, George!” More importantly, he challenged the audience.

Nobody comes to Florida, so the logic goes, because it's not worth the money and travel to get there with the crowds that show up. He said he was determined to go to Florida and make it work. Orlando, the crowd he played to the night before, was so energized and positive, he said, immediately taken aback by the rumble of hisses and boos he got from the Miami audience. We had stepped in it now. Unless Miami showed up for him and proved we were better than Orlando, he said, he couldn't justify coming back. This was on us.

And I think the entire crowd took that to heart in a way I've never really seen before. I've been to a lot of shows. Over the last year or so, me and Melissa have gone to see Thursday, Traitrs, Cursive, Molchat Doma, The Cure, and Cold Cave – twice. I've seen a lot of bands before that, during my concert-going twenties, and Melissa far more than me in hers. This isn't to say that those artists didn't put it all on the stage, because they absolutely did. The last time we saw Cold Cave, frontman Wesley Eisold was practically begging people to get up and dance.

Even so, never in my life have I seen a room full of people so determined to have a good time. That probably sounds strange. People don't go to concerts to have a bad time, right? But the mood in the room changed. This wasn't just a show anymore. We were on a mission to appreciate some live music more than we ever have before.

The crowd sang back louder, clapped louder, danced harder. That bucket hat guy kept screaming “I love you, George” and “Thank you, George” between songs. Anyone who tried to talk back was playfully swatted down to the cheers and laughter of the crowd. Even the fangless attempts at heckling felt reverent in their own way.

The thing about George Clanton is that these feelings aren't hard to inspire. He seems like he doesn't care, calling his work “making nerd music with a computer,” but I've never seen an act work harder. He's just one man on the stage: going from the sound board to the mic, picking up his guitar to play a song, setting down the guitar to go back to the sound board, stopping between tracks to work the crowd while he sets up the next song.

It has the energy of a heel wrestling promo. He serves the role of a bad man with a mic whose heckling is met with cheers and laughter instead of boos. In the middle of all that, he's climbing up on the edge of the stage to pour water on himself and the crowd, or climbing off the stage to run around the bouncing audience as people tug at his clothes and grab at his face.

Clanton makes it look easy, because we know it's so hard. If it wasn't, he wouldn't be doing it. He’s a DIY artist, touring musician, and small label owner who makes his living like this. Getting on stage by himself, with all his equipment, throwing himself at the crowd. Stoking this wink-for-the-camera-style animosity for the audience who eat it up and hoot and holler for more.

The way he produces and performs music. The extremely crunchy DIY vibes of his videos. The way he layers sounds and draws on stylings of decades past to convey a deep study and appreciation rather than simple affectation. All of it speaks to a love of the medium that gets inside your bones. You have to dance, you better dance, because this guy has worked his ass off to make this and put it in front of you.

This is why, for all the artifice and pretense, the jokes and the heckling, it all felt so…transcendent? I don't quite know how to describe it. Imagine a higher kind of reality, a moment that looks and smells and feels more. Clearer, crisper, brighter. Without a drop of alcohol or a puff of anything to alter my perceptions, the moment felt so important on its own terms, more important than any other concert-going experience I've ever had.

The cheeky rudeness and playful animosity doesn't detract from that experience, at least not for me. Rather, it highlights the performative nature of Clanton's shitpost persona and our expectations of vulnerability in art. We expect someone who speaks so candidly about such bleak feelings to be meek on stage, to perform their vulnerability in a way that makes us feel comfortable with, perhaps in control of, the situation.

Instead he's antagonistic. While his music lets you in, he doesn't have to, and so he won't. You paid money to see a show, so shut up, stop talking, and do what you're told. You're here to dance. Stop thinking and talking and trying to outsmart him by coming up with clever stuff to yell and just dance.

Feel something for once in your miserable life.

At some point, standing on the edge of the stage in a sweaty white shirt and leather jacket, sunglasses askew, backlit by the wall of white pixels projected onto the stage, Clanton clutched the mic and poured water down onto the heads of screaming, smiling people reaching up to him. It looked like a baptism or a spiritual cleansing. I laughed aloud at the thought as it struck me. It was just a bottle of water. This was just a bar show. There were no gods in the room that night.

The immediacy of the image still gave me some pause, as did my instinct to chase away the thought. There was no holy ground to protect here, no tradition to maintain. I never felt that way going to church as a kid during my brief stint as a real deal Christian. I studied at Sunday School and memorized scripture. I made little art projects about Christ and received a certificate for reciting scripture in front of the class. I listened to the youth pastor preach fire and brimstone on Wednesday nights, explaining to the children of this little Missouri town that the souls of our friends, siblings, and cousins were ours to keep from the flames of Hell.

As a younger child of five or six, I was prone to seeing devils everywhere. I was convinced that the burns left in the carpet by my smoker parents were portals to Hell. One day, these portrals would open up and I would fall into the pit of flame and sulfur. I didn't tell my mother about that for many years. Partially out of embarrassment, partially out of the lingering suspicion that I had somehow been right. I was just an anxious child with neglectful parents, but isn't that what the great deceiver would want me to think?

It's funny that I've always believed in Hell but not Heaven. To this day, Hell feels more likely. My precious few months of salvation praying and attending church didn't do much to help that.

I once watched a girl I went to Sunday School with be baptized and reborn in Christ. She proudly endeavored to wash away the sins of having addicts for parents. It was all anyone could talk about for weeks. I was ten and I think she was a year or two older, and yet the fate of her soul was a matter of public discourse. To this day, I can't tell you her name or what she looked like. She's just an outline in my mind now nearly thirty years later, a stocky girl with wavy brown hair and a forgettable face. But I will always remember bearing witness to this.

I stood waiting alongside her at the pulpit as the pastor gave his sermon. She asked me and another girl from class to stand with her. We were her rocks, the only kids who ever spoke kindly to her. The pastor explained why we were all gathered there as a community and the gravity of the occasion. Her parents, now sober and walking with God, whose names were still spoken in hushed tones, held each other's hands with wet, red eyes. My stomach did somersaults. My hands were wet and clammy.

Could you be born again like that, I wondered? Could Christ erase your family's ties to you, and with them, your sins by association? Would she be legally free of them now? Could they be punished for doing drugs, in this world rather than the next? What a world it must be for people who believe in things like Heaven.

When the pastor said whatever he needed to say, he dunked the girl in what can only be uncharitably described as a fancy trough. She came up gasping, though it had only been a few seconds. Something must have happened, I thought. It must have worked. Me and the girl from class surrounded her, taking her burdens as they slipped from her small shoulders. We held her up and carried her back to her parents. Sobbing, limp as a doll, her hair wet from the holy water as a river of relief washed over her.

Finally, she was clean. Finally, people would stop judging her for rotting away unbaptized by parents too busy getting high to tend to her spiritual needs. Finally, God would love her and people would leave her alone.

I was supposed to be happy for her. I cried and congratulated her as I helped carry her to the pew beside her parents. Born again, fresh and new. She collapsed there, sobbing, as her parents took her into their arms. I felt sickened in the pit of my stomach, as if I had just witnessed a great tragedy. Still, I smiled and clapped.

I didn't see God with us in the chapel that day. I didn't see Him in the bar that night, either. It would be strange if I had, I think. A touring musician who posts bad selfies doesn't deserve to have that much responsibility heaped at his feet. But standing in a little room full of people, determined to experience joy, with open eyes and mouths and hands, jumping and screaming and dancing together, as the shitpost framing it all melted away in white light

I mean

That's what art is for, right?

We are suffering and dancing together.

We are processing our pain together.

We are joyful and alive together.

The crowd didn't solve anything at that show. We didn't make anything better. We didn't change the world, or even the material trajectories of Clanton's or our own lives in any major way. But it felt like something inside of me shifted in that moment, a piece moving out of alignment to find a new place to rest.

That's worth something.

I have to believe that it's worth something.

Photos courtesy of Wikipedia and 100% Electrionica.

Add a comment: