Even More Stories Living Rent-free in My Head

Looking back at 2025 through the lens of art, if only to make sense of it for myself.

I hate writing the first newsletter piece of the year.

It's the worst. Well, maybe not the literal worst, but it is awkward. Like clearing a hoarse throat. Every time I do, I find myself straining to find some cheeky comment about what came before. To put it in a context I can feel good about.

It feels a bit cheap to me, that instinct to editorialize, even as I do it. Cracking a joke has always been my way of exhaling. In general, I don't look forward to the new year so much as I'm happy to see the last one dead. Telling a joke makes that feeling a bit nicer for the public reading this newsletter. As you can probably guess, people don't invite me to New Year's Eve parties.

In 2024 and 2025, I sidestepped all of that with my Three Stories Living Rent-free in My Head pieces. These are my year-in-review write-ups, looking back at the art and fiction that I engaged with in the past year. Writing my mini-reviews lets me get out a lot of thoughts and feelings that were too loose, too undefined, to fit into any other framework.

They also help me try to put those thoughts and feelings into a tidy little context. Thinking of your life as a sequence of encounters with art makes the unpleasant stuff a bit easier to look back on, you know?

In 2026, I'll do it again, if only to spare you the bad joke. I'm not exactly laughing about the events of 2025. I also see no point in acting as if 2026 means a clean slate and good vibes. At time of writing, America has attacked Venezuela and kidnapped its president Nicolás Maduro, ICE has executed an American citizen in broad daylight, multiple cities across my country are under siege by both state and federal forces, and the numerous ongoing genocides continue unabated around the world under the auspices of corporations and empires alike.

Solidarity with oppressed people everywhere. Solidarity with everyone fighting back against the horrors of empire, both at home and abroad. May we one day drown our oppressors in the oceans they poisoned and plant trees in place of their monuments.

For now, all I have to offer are my humble thoughts on the art that's touched me over the last year. I hope that's enough.

For the 2026 edition of this little piece, I'm going to do something a bit different. I don't actually have three stories to talk about. I have many stories from 2025 that stuck with me, kept me chewing on their language or themes months after I finished with them. Too many things, honestly, such that it makes it a bit difficult to talk about in some coherent way.

But, at the end of the day, there's only one story that I've thought about every day since I sat with it. That I've returned to multiple times since that first viewing. That I think really did something important for me.

So I want to talk about the runners-up first. These are the other stories that nearly made the cut, or I talked about in prior drafts of this piece, or I just talk about all the time anyway. They are more than worthy of your time, and I want to give them the attention they deserve regardless of any year-end lists or newsletter opining.

Fleischerei by Saoirse Ní Chiaragáin

When I sat down with this novella, I did not expect to devour it in a single sitting. The text itself resists such a reckless, almost naive approach. Starvation, self-mutilation, and cannibalism; social decay, sexual violence, and medical trauma. All of it is rendered with an ambivalence that dares you not to flinch. Rather than flinch, I fell into the deep, bloody, pool of Ní Chiaragáin's prose, swallowed by it.

The language is knife-like in its precision, peeling back the layers of Orthlaith’s psychology to expose the banal horrors that make up her life. This is a story about obsession, love, self-loathing, ritual, capitalism, misogyny, burnout, eating disorders, the internet, and so much more. It is unrelenting in its exploration of the woman's body as a site of violence. Social, psychological, patriarchal, sexual, all dismembering Orthlaith -- encouraging her self-destruction -- piece by piece.

There's so much here in this slim little book, a deeply rich and complex horror story. It doesn't moralize or offer shallow platitudes. The text never holds your hand or spoon feeds you resolution. You're left alone with whatever the novella drags out of you, whatever you see of yourself in its events. I appreciate that so much.

Ní Chiaragáin is a clear, bright, and vital voice in contemporary horror. She should be counted among the greats. If you can stomach it, Fleischerei is a powerful work that deserves your time.

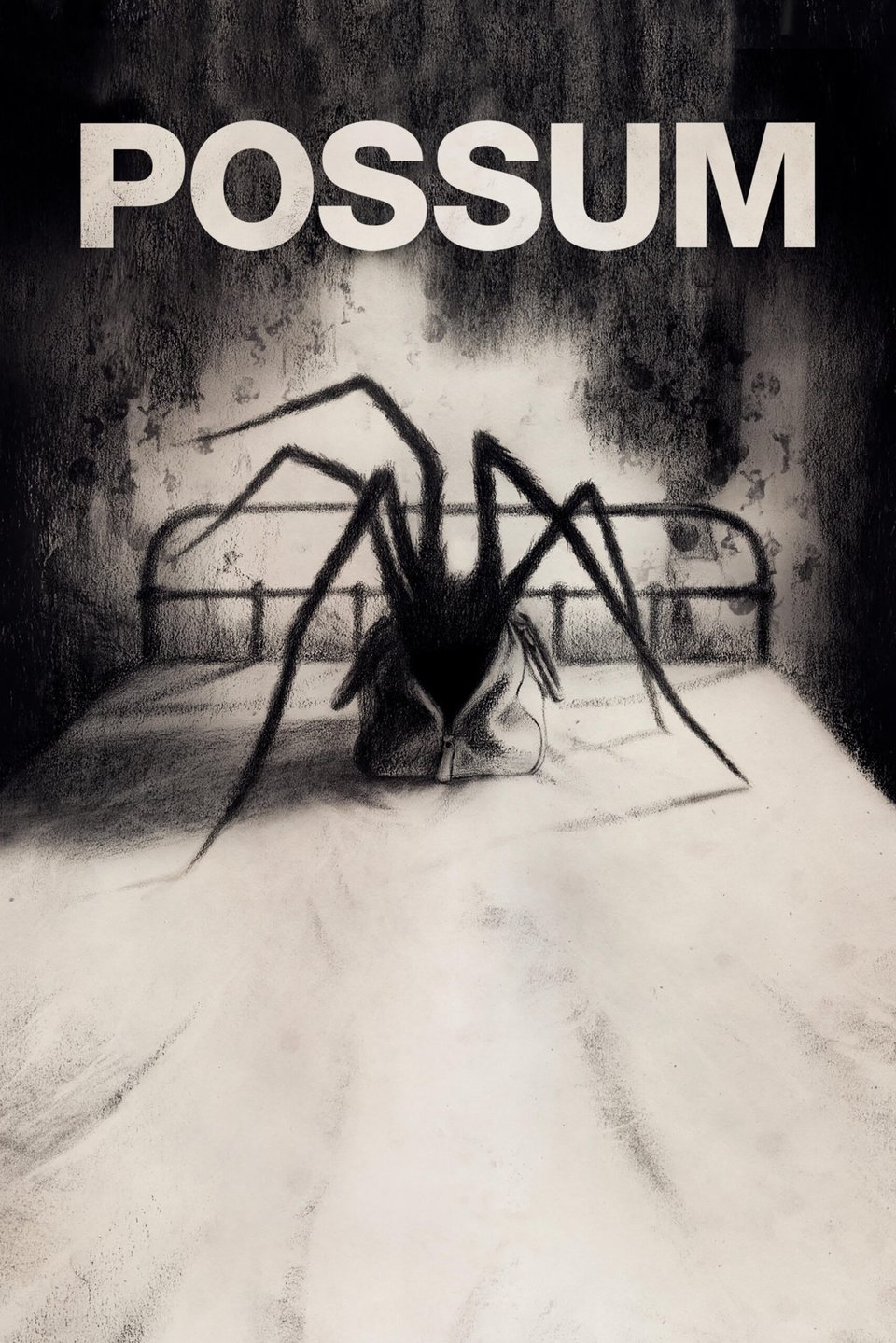

Possum, 2018. Dir. Matthew Holness

In a contemporary horror landscape that's frequently preoccupied with trauma, I find that few stories are willing to commit to their own subject matter. Trauma is often ugly. It is off-putting. It is pathetic. It makes others wary of you. It cries and trips and falls in the mud, a sickening, dirty thing that you have to hide from everyone.

Matthew Holness’ film, adapted from his short story of the same name, is a visceral Freudian nightmare that understands this very well. Through Philip, a disgraced puppeteer who returns to his childhood home, Holness unravels the lifetime of horrors produced by childhood loss, trauma, and abuse. The titular Possum is a spider marionette with a human face that looks eerily like Philip's. The puppeteer carries it around with him in a bag and spends most of the film's runtime trying to destroy it. Burn it. Drown it. Leave it in the woods.

Yet Possum always returns. It crawls into Philip's bed at night, appears in windows and in the corners of rooms. Philip is afraid of it, yet it's always there, stalking him, overpowering him, until it doesn't. Possum is…intimate. It knows him, embraces him. It is the knowing touch on Philip's cheek or the uneasy familiarity experienced when he presses their foreheads together in those brief moments of…peace? Surrender? Acceptance? It's hard to say for sure.

What first appears as a troubled man's homecoming dissolves into a surreal confrontation with his abuser, the specter of his uncle Maurice. His uncle is a sneering, impenetrable man who haunts his dead parents’ burned-out home. Maurice's presence, the very thought of him, is enough to make Philip visibly uncomfortable. They circle one another, like predator and prey, as a local boy's disappearance heaps greater and greater suspicion onto the already unwell Philip.

Philip is a victim falling through decades of unprocessed, untreated horror, regressing into a helpless state as he struggles and fails to cope. Yet…that's also too simple a picture. Too neat and clean for the story that's being pulled apart here. Philip, played with quiet alienation and desperate unease by the pitch-perfect Sean Harris, is a deeply broken and tragic character. But he's also unreliable. His relation of events is not only confusing, it is increasingly unlikely, even impossible, as the story goes on.

Sometimes, some kinds of abuse create monsters of their victims. It's never outright stated, nor is it treated like a lurid twist. The film's hypnotic surreality and disjointed, dreamlike pacing create enough dissonance to obscure the hard facts of the plot. Philip is struggling with much more than just the horrors done to him. Through this slowly unfolding realization, you are left with that knowledge like a pit in your stomach.

As Philip cradles Possum's head and his wet gaze draws distant, you sit with both your empathy and your revulsion, watching a man come to fully understand himself in every facet of his existence.

Just as trauma is often ugly, healing from it doesn't always provide comfort. Catharsis, resolution, yes, but not comfort. It's in that unwillingness to ease my mind and give me simple, digestible answers that Possum has continued to haunt me. It's a wretched, oppressive film that speaks to the kinds of suffering that daily go unspoken, and I remain grateful that it exists to give voice to such horrors.

The Works of Product

When I say that one of the most singularly fascinating voices in independent horror filmmaking right now is a twenty-something animator who used to make entire short films on their smart phone, I'm being deadly serious.

Product is a wholly unique and compelling creator. Their work is surreal, disturbing, gory, funny, and campy in one unapologetic package of hard femme glamor. Think John Waters by way of Tobe Hooper, if either of them made their films using Sims 2 character models. Laugh-out-loud funny one moment and distressingly gross the next, all while remaining unflinchingly sincere in its emotional content. Product's work is, by their own description, semi-autobiographical. They use the grotesque and farcical to prod at the rotting core of the suburban experience. And they don't pull any punches.

Big houses with curtained windows hide terrors behind them. Parents abuse and neglect children who grow up to abuse and neglect their own children in turn. Mothers cling to the promise of validation and fulfillment offered if they perform womanhood, motherhood, to perfection, even as their husbands prey on the children they claim to love. Cruelty begets cruelty in cycles that only ever seem to end in mass casualty events.

While not always the most successful in the terms of executing on the stated themes of the overall project, Product's films are worth experiencing for yourself. Their most popular work, the Mother trilogy of domestic horrors, is a truly stunning series of animation. Mother, Alice, and Father are triumphs in and of themselves and deserve the attention they've received, even for my own personal criticisms of their overall narrative effectiveness and thematic impact.

Also, my heart remains loyal to Dirty Donna, the mean-spirited and grimly funny film about a woman who loves cigarettes more than anything. And hates kids even more. Donna is the best character in the entire Product roster. I love her more than Mother, and even more than Soleskiss. There, I said it.

One day, I want to return to Product's work to write about it (and my criticisms) in more depth. For now, I will say that if you're interested in an up-and-coming short form horror auteur, Product is absolutely worth your time.

Now, it's time to take a deep breath. We have to talk about the story that pushed me to write this in the first place.

KPop Demon Hunters, 2025. Dir. Maggie Kang & Chris Appelhans

To be completely frank with you, I really struggled with the fact that I wanted to dedicate an entire piece of writing to this film.

None of this is a slight against the film itself. It made its way to this list of stories living rent-free in my head for a reason. I probably don't even need to introduce KPop Demon Hunters at this point. It's so staggeringly popular -- near universally beloved, even -- that I can't throw a rock without hitting twenty pieces of hilarious knock-off merchandise at my local mall. The mere image of Rumi, Mira, and Zoey (however fuzzy and off-model they may be) on a cheaply printed box is enough to make somebody a pretty good chunk of money.

It is also beautifully animated, perfectly scored, and well-performed. It's cute without being cloying, funny without being insincere. Kinetic visuals and diegetic music make the fantastical elements of magical girl idols and gorgeous demon boy bands traversing the different planes of existence not only engrossing, but an absolute joy to watch. Overall, it's just…good!

I don't think I have a single critical thing to say about the movie, if I'm being honest. That doesn't necessarily mean much, of course, which is also worth stating here. My understanding of Korean popular culture and historical iconography is quite limited. It was primarily absorbed by engaging with other films and film criticism, especially in terms of Korea's complex political history. That and editing a friend's novel-length K-Pop idol fanfiction, which I won't go into detail about here, but was also very enlightening.

There are other critics out there who are far better equipped to discuss those nuances, is what I'm saying. I'm sure there are parts of the film or those discussions that go right over my big fat American head. What I can say is this:

KPop Demon Hunters is a perfect film to me, in how well it executes on the story it sets out to tell.

Every time I watch it, I cry.

Every time I listen to the soundtrack in my car, I cry.

I also cried during the performance of Golden during Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, a thing I only ever watch to see the Goku balloon and maybe the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles float.

Rather, what made me struggle with writing this is just how much it moves me every time I sit with it.

The kinds of stories that I naturally tend to seek out are…challenging, let's say. They use ambiguity and metaphor to muddy the viewer's understanding of the world and its story. They can be subversive, opaque, even contradictory in how they tease out the meaning. Do you think I can tell you definitively what happened in Tony Domenico's Petscop, or David Lynch's Lost Highway? Absolutely not. Sometimes I think that I know, and then I remind myself that I'm better off trying to feel my way out of the thicket rather than try to proclaim mastery over the subject.

KPop Demon Hunters is so straightforward, so earnest in its nature as an all-ages animated feature, that I was caught off-guard by what it had to say.

Rumi, Mira, and Zoey make up the K-Pop group Huntrix, the latest generation of demon hunters. They are young women who use their powerful voices in a spiritual battle against Gwi-Ma, the demon king. The hunters’ singing voices create and maintain the Honmoon, a spiritual barrier between the worlds of humans and demons to seal out Gwi-Ma's influence. Once the Honmoon is strong enough to close the gate between their worlds, it will protect humanity from demons and end the war between Gwi-Ma and the hunters forever.

But Rumi, daughter of a hunter and a demon father, bears Gwi-Ma's mark on her skin. Her adopted mother, the hunter Celine, taught Rumi to hide her demonic patterns. Celine tried to instill strength in Rumi by teaching her to hide this secret, but a child of two worlds, Rumi lives in fear and shame of both. She hates demons yet closes herself off from her closest friends, projecting a perfect, hardworking, almost dogmatic persona to hide within. She pushes everyone else around her harder and harder to seal the Honmoon, which she believes will erase the patterns from her skin and rid her of her blighted heritage.

A less competent story would have shown Rumi learn to overcome this inconvenience and see her heritage as a quirk. A matter of confidence rather than life and death. Everyone would cry, hug, and get over this little speed bump, all the better for it. Instead, KPop Demon Hunters lets Rumi unravel. She's self-loathing, albeit in less outwardly destructive ways. She aches to be loved by people who have rejected her for these things she can't change. She lives at the knife's edge of fear and shame, always poised to fall into their clutches. Anger's, too, her rage boiling over in the rare moments she loses control of herself.

Through her relationship with the demon and rival idol Jinu, Rumi comes to understand the reality of her demonic half. Instead of mere monsters, blunt weapons wielded by Gwi-Ma, demons are humans twisted by guilt and shame for their past actions. They are not sinful, as there is no hard moral implication to the actions of the demons, but they have done wrong. By their families, their communities, themselves. For it, they are suffering.

Shame isolates. It burns. Destroys. But not on its own. Shame polices because society uses it to patrol its boundaries and decide who's worthy of light. Of love. People consumed by their shame turn away from society, rejected by it, cut off from their communities and expression of essential humanity.

After carrying this burden for so long, they are relegated to the dark. They see no other way out, unable to forgive themselves or seek the forgiveness of others without the support necessary to do so. Trapped by the narrow confines of their own pain, they fall into the demon king's domain. Gwi-Ma places these lost souls under his spell, their heads filled with his soothingly hypnotic voice. Dehumanizing them. Distorting them. Denying them a path toward the light.

This is a pretty dire read, I know. The coding for other, more relatable experiences is clearly expressed in Rumi's story. It's telegraphed in Mira's and Zoey's, too. The shame broadly speaks to themes of queerness, biracial identity, neurodivergence, or anything else that breaks from social roles and expectations. I can see how one arrives at one or more of such reads. I can absolutely see their value, especially for younger audiences and their families who likely don't often get to see such messaging rendered with so much craft and care. However, my takeaway is different.

In rooting Rumi's story in a profound and dangerous difference, the film manages to do something more interesting with it. Yes, skin color, queerness, and neurodivergence can all make you the target of violence, on both systemic and interpersonal levels. But a demon is no longer human, in the strictest sense of the word. A demon can kill, and so demons must be killed. It isn't about learning to love herself despite her differences, or overcoming the obstacles they pose. The stakes are simply too high.

There is no other path forward by the time the war with Gwi-Ma draws to its conclusion. Lying and hiding caused her pain. Internalizing Celine's teachings made her hate who she is. Rumi is so consumed by the promise of freedom when the Honmoon is finally sealed that everyone else in her life falls to the wayside. Shame and loathing change the shape of who she is, and puts limitations on who she is allowed to be. The order of things as it exists now will see her dead.

This order, this generation-spanning system of ritual and ideology, must change. Rumi must learn to accept the darkest, ugliest parts of herself. She must integrate her shame, anger, and fear into her person and live with them, like the patterns on her skin. If she does not change, if she succumbs to despair placed in her heart by those who couldn't accept her, then she isn't going to make it out of this alive.

You can probably see why this movie makes me cry every time I watch it.

But Rumi does change. She does accept who and what she is, and takes those broken parts inside herself instead of shunning or hiding them away. The patterns don't disappear. Even as Huntrix reunites to defeat Gwi-Ma and seal the Honmoon, Rumi still bears her scars. She isn't absolved or purified the way she had always hoped, but she is changed.

That, to me, is such a nuanced and mature way to frame these struggles. It isn't simple. No amount of positivity or self-mastery can make it all go away. Such deep, dark, ugly feelings can't be pushed aside to make room for ones that make people more comfortable around you. Healing isn't a performance for the approval of others.

Rumi is still half-demon, and she is now able to walk in the light, because both halves deserve to live in the sun.

You and I, no matter what lies we are told and the depth of pain we carry within us, we all deserve the same.

And that's why this silly cartoon movie about magical girl idols and gorgeous demon boy bands continues to live rent-free in my head.

Add a comment: