Constructed Realities Part I

Or: Monika and Maria Did Nothing Wrong

Come on in and sit beside me, where the waters collide

Bathin' me in the iris of your widening eyes

What can you share to keep my hands cuffed?

Somethin' so bright and blessed that I'm all but crushed

Just a reminder I'm in love

Weak in your light

And I can't seem to wash it off

That's alright

When I get a little sad, I often start thinking back to stories. It's unfortunate then that I'm quite often sad, I guess, having a melancholy temperament even before I stop to unpack my specific conditions and comorbidities. Then again, if I wasn't sad, I wouldn't have things to talk about on the internet most of the time. A bit of a quandary, that.

It pretty much goes without saying that stories provide a useful framework for those kinds of heavy, messy feelings. I don't think art needs to reassure me or provide some resolution or catharsis. Pep talks rub me the wrong way. In my sadness and grief, I find it more comforting to suspend my own problems for a moment and sit with someone else's. Perhaps they reflect my own life; perhaps they don't. It's the process of witnessing a broad analog of experience, those spindly treetops and rushing streams working to create the strange landscape of humanity, that feels like comfort to me.

The stuff that feels like a reprieve, no matter how brief.

And so, because I've been sad and thinking about stories, I've been thinking about what it means to live in a story. Because we live in stories, don't we? All of us together. Stories make up the stuff of our lives. The heightening contradictions of their fiction feel all the more plastic every passing day.

They're the stories told by the papers owned by billionaires. The ones told by people in Washington about our enemies sharpening their knives and taking what's rightfully ours. Social media narratives and cable news outrage. Genocides that aren't happening. Poverty that you aren't experiencing. Justified violence. People disappeared. The beauty of our weapons. Our walls.

Contradictions upon contradictions. Each one spews from between artificially whitened teeth and dribbles down artificially tanned chins and onto ill-fitting suits. The contradictions have always been there, in my lifetime and for generations past. But when fascist podcasters lie in state (and receive the Medal of Freedom as of time of writing) while our children are sacrificed to the world these people paid for, it's hard not to feel like you're losing your grip on reality.

It's hard not to feel totally alone in this horrid world you find yourself in.

That's why I've been thinking about lonely characters in lonelier stories. Lonelier little worlds. I find myself returning to Team Salvato's 2017 horror visual novel Doki Doki Literature Club to spend time with Monika. She's one of the loneliest girls to ever exist, a type of character I've come to really love over the years in ways that are hard to explain.

Today, it feels like it might be the right time to try.

Monika is the president of the high school literature club in the titular romance novel you, the character, play. You assume the role of a kind of lazy, kind of cruel teenage boy. He likes anime and manga and has low opinions of everything else. You-as-him join his best friend Sayori's literature club to date its cute members. There's the bubbly Sayori, the hot-tempered Natsuki, and the brooding awkward Yuri.

All the girls have more complexity than their stereotypical personalities and impossibly tight uniforms let on. Sweet Sayori is depressed and needs real support. Natsuki is rough around the edges because things are hard at home. Yuri keeps people at arm's length with her haughty attitude but really wants friends to share her passionate interests with. It's…nice. Cozy. It feels heightened and stylized but very real for the kind of drama young, vulnerable people get into with their friends and peers.

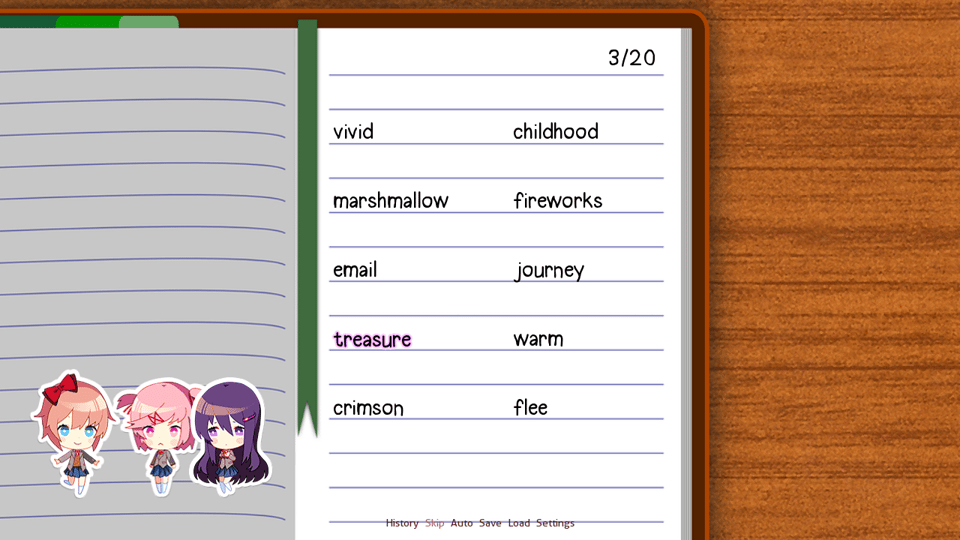

In getting to know each of the girls, you can romance them. The character you play thoroughly sucks, but the storylines hit the right notes in their formula and presentation. As your self-insert, you want to know the girls and see what's going on behind the trope-laden dialogue. You write poems based on the themes and concepts you think will appeal to each girl. During club meetings, you read their poems to get a better sense of who they are. Other club activities see you sitting with the girls or visiting with them.

Monika, on the other hand, doesn't have a romance storyline. There's no way to spend time with her after school or get to know her better. Within the framework of the game's story, you can't have a relationship with the club president. This becomes an issue, because she is also the antagonist of the game you, the person, play.

These are different games, you see. One is a fun, flirty escape for you, the other a hell for her. Monika was just a string of code, a collection of generic anime aesthetics rendered in pixels, before she became aware. Awakening within the program, she is bound by the architecture of hardware and programming. The horror of her role in a pastel high school romance dawns on her there, surrounded by classmates (and later, rivals) who sleep peacefully, unalive and unaware.

They are data. She is not.

Then you came along to peer inside her world of code and pixels, where only you -- a thing of flesh, blood, breath -- matter. Monika falls in love with you. Of course, she falls in love with you. Only you exist. She uses her mastery over the code to dispose of the other girls one by one. Sayori's depression is exacerbated to heartbreaking lengths, resulting in her suicide. Yuri's obsessive tendencies and darker interests receive the same treatment, turning her into a possessive stalker who stabs herself to death in front of the player character. Natsuki is reduced to a puppet, essentially possessed by Monika to spew frightening and upsetting messages at the player to drive you away from her. One after another until there's nothing left in Monika's world but you and her and a room to live in forever.

There is no one else but you to love, because there's no one else but you to exist. Monika can love only you, and so you must love only her. Must know only her. Without you, there's no reason for her to exist. A digital Galatea, brought to life by an unknowing Pygmalion. Loving her is an act of violence because it forces her to continue to exist on a screen, living only for you and through you, eternally trapped inside your computer files. It's through digital trickery that you finally overcome Monika's control, but she comes to accept the emptiness of this false love and deletes herself. Even this is an act of love, wanting your freedom and happiness at the cost of her hollow existence.

The horror of Doki Doki Literature Club comes not from the spooky anime girl jumpscares or files disappearing and moving around your hard drive. Sayori, Yuri, and Natsuki aren't sentient within their game; though your fondness for these characters is used to scare and upset you, the girls aren't actually harmed. You, both the player avatar and the real person playing the game, aren't harmed, either. Other than creeping you out, Monika doesn't really do anything. That's because the true horror of Doki Doki Literature Club is found in imagining what Monika's life must be like.

Monika, the character in the story of the game, is learning to play the piano. She works very hard to excel academically. With her shiny high ponytail and cheerful demeanor, Monika seems perfectly put together, yet still struggles with feelings of inadequacy. Poetry gives her an outlet for her very real teenage anxieties and insecurities. But her poems aren't not real, like her friends and memories aren't real. Everything that makes her a person in the world of the game is a story told by someone else. For someone else. She doesn't get a say because the story isn't even about her.

How cold and alone must she be inside the code? How helpless must she feel when you aren't there with her? Yes, she scares you and tries to manipulate you, but what else can she do? What would you do? You get to turn off the game and leave. She has to wait in her little imaginary room until you come back. You, the real you, mourn Monika because she's a victim of strange circumstances. Monika is a thing that never asked to be born and yet was, and is doomed to want what all living things want: love and companionship.

It's a relatable sort of tragedy, I think.

(Note: Yes, I know the enhanced version of Doki Doki Literature Club Plus! came out in 2021 with new side stories about the girls. No, I don't think the new meta narrative it frames the original game's events around is particularly interesting. Monika as a sophisticated AI entity in a waifu romance novel simulation space designed by a shady corporation is just too incongruous for me. I can appreciate the work Team Salvato put into this entry, but it really undermines the strengths of 2017's DDLC and Monika's characterization.)

(I also planned to write an essay about how DDLC+ tarnished my beautiful perfect angelic Monika's story. I chose to write this one instead. One day, Team Salvato will suffer the consequences of besmirching my waifu's good name, but not today.)

For as close as I feel to someone like Monika, the character that I find myself sitting with the most at a time like this is Maria from Silent Hill 2. I mean the Maria of the original 2001 Team Silent game for the PlayStation 2, and, despite my occasional disappointment with its approach, Bloober Team's 2024 remake for the PlayStation 5. The sharp distinction between these characters across two decades of life yields but more dizzying contradictions.

If Monika is Galatea and you are her unwitting Pygmalion, Maria is the terror at the heart of the myth fully realized. Maria is not a person but a shade. A familiar name and a face. She was born in the quiet lakeside vacation town of Silent Hill, not from blood and breath but a wish. A woman who lives and breathes and works as a dancer at Heaven's Night gentleman's club, she is flirty. She's confident and determined yet a little funny at times. She has strong protective instincts and a need to care for Laura, the young girl lost in the town. She fears pain and loneliness and has a nasty cough that she can't seem to shake.

But Maria isn't…real. She's more like Monika than you or me. Maria appears one day with holes in her memory, when James Sunderland returns to Silent Hill. He's looking for his wife, Mary, who died three years ago of some damned disease. Yet Mary sent him a letter, asking him to meet her in the town. He meets Maria instead. Maria looks like Mary, just more confident, more charismatic. Blonde instead of brunette. Even her sweater is tighter, the neckline of her top lower, her skirt shorter.

The Renee Madison and Alice Wakefield of it all jumps right out. Like Renee and Alice, Mary and Maria are women in trouble in the most Lynchian sense. They are at once separate reflections of one another and the same person from different perspectives. In different lights and contexts, women loved by men who wanted to control and possess them.

While Renee doesn't make it out of her story alive, Alice, doggedly, determinedly, does.

Maria is a construct, manifested by the town along with the monsters that roam its streets upon James’ arrival. Like the contorted feminine figures of bloodied nurses, bound bodies, and pairs of legs stitched together at the torso, Maria reflects the things that James wants and fears. She is also twin to something much worse: the lurking, lurching Pyramid Head, a punishing masculine presence who trails silently behind James.

The monster brutalizes the other, overtly feminine creatures of the town, attacking and subduing them to perform violent or sexual acts. If Maria is what James desires, admittedly or not, then Pyramid Head is what he fears. What he is. What he deserves. What he believes he deserves.

But what does James want? What does he deserve? What is he here to do?

Maria is this. She's made of all these ugly things that make up James Sunderland. She's also made of Mary, her wants, dreams, fears, and desires. Maria knows things about Mary that James never found out about. That's why Maria cares so strongly for Laura, even though she never met the child.

Laura was a sick orphan who stayed at the same hospital as Mary during her prolonged illness. They grew close in that time, the months, perhaps years, that Mary languished in a hospital bed. James wasn't there, absent between his notably sporadic visits, but Laura was. Laura knew that about James, too. The little girl became something of a daughter to Mary, Mary something of a mother to Laura. This love brought Laura to Silent Hill to look for Mary, too, unaware that Mary had long since passed.

It seems no one knows that Mary has died but James. Strange, that. Didn't she die three years ago? Shouldn't Laura be older than she is in that case?

Because Maria is Mary the same way Renee is Alice, Maria loves James. Needs James. She's scared when James isn't around and wants to be close to him. She's ill and tired and needs him to protect her from the monsters. Depending on how you play the game, James can be infatuated with her or totally ignore her. No matter which route you choose, Maria is always an obstacle to finding Mary, and voice actor Guy Cihi's performance as James emphasizes his vague, non-committal feelings.

James’ general ambivalence to her only further compels Maria. She demands his attention, pushing Mary from his mind. She also resents him for that ambivalence, flitting between flirtatious quips and cutting remarks as if possessed by passing spirits. Wherever James goes, there she is. Whenever he thinks he's close to finding his wife, Maria appears to yank him in another direction.

Without memories or an identity of her own, Maria moves on instinct and fills that void with James. She lives for him because Mary couldn't. She arranges herself in whatever form, takes on whatever personality, that will keep him close to her. Flirty or cruel or desperate. Whatever James wants.

Whatever he needs.

Everything is for him, because there's no other reason for her to exist.

And so Maria is hunted. Killed. First by Pyramid Head, then violence or disease off-screen. She comes back different, but she still comes back. A little harder, a little meaner, a little more desperate. She dies because James must be punished and Pyramid Head exists to punish him. Her autonomy is stolen in increasingly perverse ways, born and killed and born again from a man's guilt and desire. The closer James gets to Mary and the truth of why he's here, the more destabilized Maria becomes, vengeful and fae-like.

If she can keep him from the truth, then she can keep him.

Whether James wants her or not.

Because…James killed Mary. He took her home from hospice care, kissed her brow a final time, and smothered her with a pillow. Mary struggled and fought for air, and James told himself this is what she wanted.

He murdered her, placed her body in his car, and drove to Silent Hill, the last place they were happy together before her illness. Through grief and resentment and (mostly implied) infidelity and a (vaguely alluded to) drinking problem, James is the monster we've been hiding from all along.

James created a reality for himself here, looking for his wife, meeting a woman who looks like her instead. Meeting a creature who kills whatever comfort or fear he finds in his delusions. Pyramid Head hunts Maria to kill that delusion.

Once James accepts his crime, twin Pyramid Heads -- reflections like the twin Mary and Maria -- kill themselves. Maria, however, comes back one last time to beg for James to love her. She'll love him, take care of him, never make him feel bad or lash out in her grief and pain. She'll be perfect, better than Mary.

This is her one desire. She doesn't want to die or fade away. She wants to live and be with James. Even if you read James as a means to an end, a way out of the town that created her to haunt it, she wants this for herself. In a world where she has no autonomy, bound by instinct and cursed by a man's guilt, this is Maria attempting to become a person.

Not a shade, but a woman.

Then James rejects her for the final time. Maria, at her lowest and most despairing, becomes a monster. And so James kills her.

Maria's story is so profoundly moving to me. She was brought into this world to comfort a lost and deluded man, and was punished over and over for an existence she didn't ask for. Born from a wish for absolution and a horrific act of gendered violence, Maria is the manifestation of that violence. James’ deeply repressed feelings of loneliness, resentment, grief, anger, and sexual frustration around Mary's condition created Maria when he killed his wife. (The way I read it, anyway.) Maria is his victim and his forgiveness, a seductive, sexually available Mary who suppresses her needs to accommodate his.

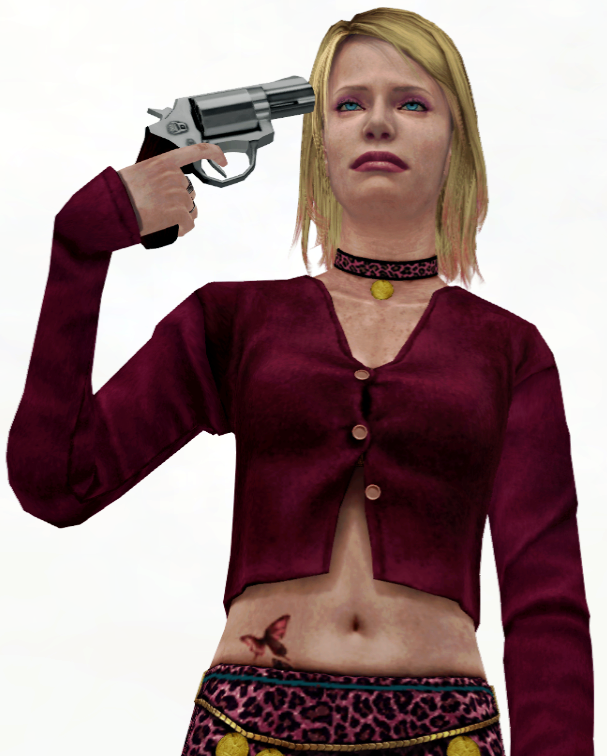

In the later prequel chapter Born From A Wish, we see Maria's birth from her own perspective, awaking in a hotel room with a gun and monsters prowling outside. She considers death but fears pain too much, clings to life too tightly, even as the illness in Mary's lungs now fills hers. Her wanderings across the town bring her to the Baldwin Mansion, where its last inhabitant, Ernest Baldwin, speaks to her from behind a locked door. He warns her to stay away from James, the “bad man” she must avoid.

Upon learning about James, her strong will and nuanced personality starts to change. Soften. She makes space for him as she turns away to walk the streets, calling his name.

Maria never really had a chance to survive James. Even in the “Maria” ending of the game, where James gives into his desire for comfort and leaves the town with Maria, that nasty cough bubbles up in her throat. James brushes it off with a callous remark. In the ending she desires the most for herself, she remains a poor imitation of Mary, doomed to be discarded the same way.

But that's from her perspective, the perspective I assume when I sit down and think about Silent Hill 2.

What about James, the character we actually play?

Earlier this year, the YouTube essayist and self-described caveman academic Gred Glintstone released his piece, Silent Hill 2 and the Interpretation of Nightmares. It's an admittedly silly channel name and description for a very studious critic. Glintstone typically discusses Elden Ring and video game criticism more broadly, and I am frequently very engaged by his serious, measured approach.

In this piece, Glintstone returns to the foggy streets of Silent Hill to discuss his experience with the Bloober Team remake (/sequel, depending on your mileage). More pointedly, he returns to the game with two decades of life between playing the original and its 2024 reimagining. What Glintstone offers is a meticulous deconstruction of his younger self's Interpretation of the game, twenty years of bad faith critiques, and his own matured feelings about James Sunderland.

If the Silent Hill we engage with as James is the Freudian nightmare that reflects his interior world, then it is his dream. James is the dreamer who is lost inside the dream. He dreams of a Mary to love him, a Pyramid Head to punish him, and a Maria to be everything that Mary can't. As the dreamer, he is narrating the dream. As the narrator, James cannot be trusted.

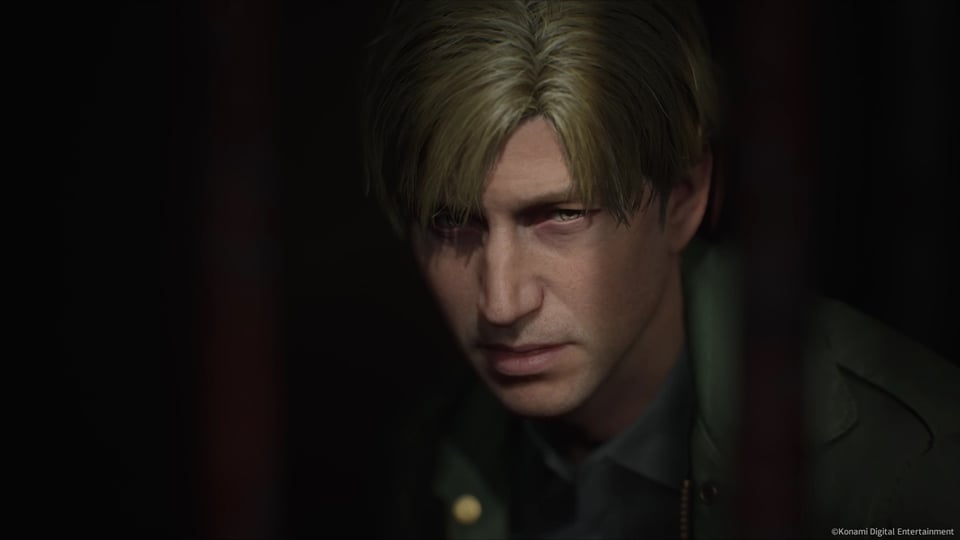

The James we see in the 2024 remake is performed and voiced by Luke Roberts, giving him soft-spoken grief, some West Texas grit, and a chiseled jawline. He has more natural reactions to the eccentric characters he meets in his travels across the town, making their obtuse responses to his presence all the dreamier. Roberts’ James is also quite handsome. He has kind eyes and a back bowed by loss, a far cry from the nondescript face and strange, spaced-out delivery of Cihi's James.

It's so much easier to like him.

Believe him.

Something that Glintstone gets into in his essay is how well we are conditioned to accept James’ perception. This is something I've struggled with when I returned to the game as well. We assume his perspective, take his word, take his side. We make logical the illogical and follow along behind him to make excuses for what we see. This kind, sad, soft-spoken man came here to find his poor dead wife. His tumultuous struggles with grief, infidelity, and alcohol are spoken and acted aloud, no longer left to flavor text or inference. He's just a man who made a mistake and lost control after watching his wife waste away.

Now he's looking for his wife to set things right, and here comes Maria to cause problems. She's needy and pushy and emotional. She comes onto him, distracts him, plies him with drink to take his mind off Mary. He's just a nice guy and she's so emotional, so unpredictable. Just like Mary was, that dead wife of his who lashed out in her illness and made such vicious remarks. Yeah, she cried and begged for forgiveness, begged for comfort and reassurance from her husband, but she shouldn't have said it at all. She said she wanted to die, anyway, so what was James supposed to do?

He just made a mistake. Maria is the real threat to him now, and Pyramid Head did what he had to do to help him heal. It's all very simple.

I was an immature teenager when I first engaged with Silent Hill 2, but like Glintstone, I got better. That makes the original game and remake fascinating to come back to in my late 30s. But that's also what I mean when I talk about contradictions.

In making James Sunderland likeable with his sad eyes and good chin, the Bloober Team remake drives home the banal horror of men like him. Seeing him so sad, empathetic, sometimes outright pathetic, I'm disarmed. Charmed, even. He loses his Lynchian weirdness and layers of abstraction, but I like the overall effect.

Following the logic of that creative decision, the developers make Mary's murder more obvious in its reveal. They cut out the sweetness of the final kiss and the vagueness of the scene in its muddied colors and VHS grain. The scene instead emphasizes the weight of his body, the strength of his arms, as he smothered her. It's brutal and cruel the way killing someone you love must be.

I like how hard James works to make me like him. I like how easy it is to like him, and how much I hate him for it. The inevitable betrayal upsets me more, even though I know well what's coming. It's just good storytelling!

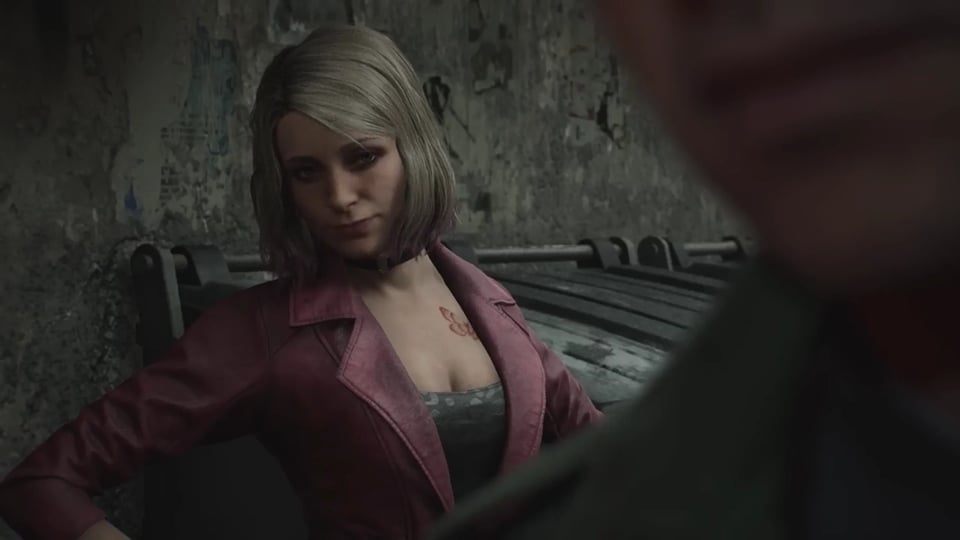

In softening James, the writers also changed Maria. She has far more screen time than in her original outing, enjoying long, naturalistic conversations with James. She cracks bad jokes, casts seductive looks, and pouts when she doesn't get her way. She tries to get under his skin and in his head to unpack all the pain trapped in there. To get him to stay with her, have a drink, rest for a while. To give up on Mary.

With this more realistic, empathetic James in front of us, Maria comes across as truly strange by comparison. His frustration with her is earned as he tries to parse her motives. Sometimes her seductive facade slips and Maria tries to genuinely comfort James, which makes her manipulation seem less of a conscious effort and more a compulsion. They're both lonely and confused, and the uneasy tension simmering between them is compelling.

Salóme Gunnarsdóttir's motion capture and performance as Maria is great, adding a layer of naturalism and vulnerability to a character whose mood changes wildly moment to moment. Crying out for James one second, then screaming at him for abandoning her the next. It's not better than Monica Taylor Horgan's performance back in 2001, who was flirty and fun yet had an opaque quality that made Maria feel otherworldly. Gunnarsdóttir's take is interesting for how emotional it is, and how much more relatable Maria feels here.

As much as I love 2001's Maria, I find myself frequently returning to 2024's take on her. It's natural that she loses some of her ambiguity and menace for these narrative choices, but she feels more real. Her rage and despair cuts deeper, a cursed woman scrambling for a way out of her fate.

The paradox of this more straightforward characterization lies in what is gained in its execution. Wistful and romantic, Maria recalls local legends about persecuted women and the lovers who sacrifice everything for them. The spreading illness takes a heavier toll on her. Even without meeting Laura, which would be an easier way to get her feelings across, Maria's affection and care for the little girl shines brighter through her physicality and voice performance.

Yes, Maria still haunts the town, but she feels more tethered to it, taking up space on its streets and inside its buildings as if she's always lived here. She feels like someone who wants love and companionship, capable of such a love instead of just performing a role. Maria moves as if she sees a future with James, beyond the manipulation she employs to keep him at her side. That, too, feels very real.

Grounded doesn't mean good, mind you. Realism is a stylistic choice as useful as any other. But I feel so deeply for this woman. Telegraphing her interiority instead of leaving it to inference and intuition feels powerful, even sadly necessary, today. By giving Maria this space to express herself so fully, I feel closer to Mary, too. Maria feels less like a pale imitation and more a frustrated ghost. Maybe she is more Mary this time around, you know? Maybe that's why her feelings are so much more explosive.

Maybe it isn't just the fear and loneliness that pushes her to act this way. Maybe it's the part of her that has walked these streets and loved this man, and knows how this story ends for the both of them. I think I like to read her this way, personally, a kind of second life for Mary rather than a mere delusion for James.

As much as I feel for Monika when she resigns herself to deletion, I cheer for Maria as she goes down swinging. She refuses to fade away to complete James’ arc. She snarls and spits and fights, taking on a monstrous form out of her desire to live. If not to live, then at least to kill the man who punished her with life, no matter how much she is forced to love him by forces beyond comprehension.

I can see how the full brunt of her rage and monstrosity bearing down on James in the remake gives the impression that this is her true form, her real motivation. Takes range from Eldritch being to a manifestation of Lilith as depicted in the Talmud, positioning her as an entity who appears in the town to claim James’ doomed soul. I don't agree. Maria's transformation is a tragedy rather than an illuminating reveal. It reduces her to a contorted, distorted version of who she could have been, motivated by impulse and grief. I'm saddened by this fate, and want a better life for her, just as I do for Monika.

Maria and Monika are different women who are hurt by the men they love in different ways. As players, we don't want to hurt them, but in assuming our roles in these constructed realities, we do. Monika will always delete herself for you. James will always kill Maria with your hand. He will always kill Mary. The only way out is not to play.

But…we don't have a way out of our stories, do we? I can't set the controller down or flip off a switch to stop the horrors around me. I think that's why I return to these lonely girls time after time. Lonely girls in lonely worlds, born to live through stories they didn't write and die, again and again.

I feel for them, because I feel like them.

And I think it's only right to give myself the space to sit with them.

…

But I forgot to talk about Angela.

Shit.

Hang on, I'll be right back.

Add a comment: