Okay So, Lemme Tell You About... The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974)

Reference Links: IMDB | ReelGood | Wikipedia

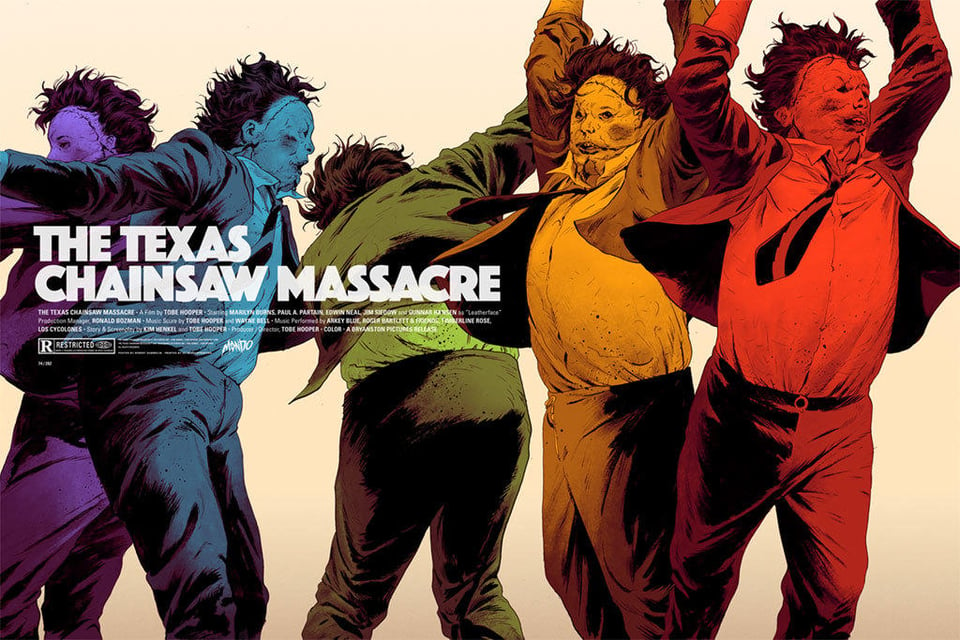

Let's start things off with a classic movie, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (film, 1974, Tobe Hooper). Not to be confused with its sequels, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (film, 2003, Marcus Nispel), Texas Chainsaw Massacre (film, 2022, David Blue Garcia), The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (video game, 1982, Wizard Video for Atari 2600) or The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (video game, 2021, Gun Interactive for Windows/PS4/PS5/XBone/XSX/XSS/GamePass). Just to be clear because searching is probably gonna get real funky and non-specific based on your interests.

IMDB Summary: Five friends head out to rural Texas to visit the grave of a grandfather. On the way they stumble across what appears to be a deserted house, only to discover something sinister within. Something armed with a chainsaw.

My Summary: Four extremely white teenagers (and one disabled younger brother who has all the precious few brain cells) believe so deeply in their untouchability that they really rolled up into a largely unfamiliar Texas town like nothing could ever happen to them because they're white and it's summer. Spoiler alert: shit happens to them.

Yes, all of my summaries are probably going to be a lot like this.

Spoilers begin here! Check the ReelGood link above now if you want to watch the movie first!

While I can see why this movie is so seminal for so many horror fans and directors, it just doesn't hit for me. I think that's because it demonizes the Other when I am the Other in life. I feel bad for Leatherface and his brother in a very abstracted way because they're stuck in a past revolving extremely literally around their ancestors. There is no escape for them, even though they survive. They are also traumatized. And they literally never learned better. They don't get to learn better. Partly because that's the conceit of a horror movie and a mythos (ask me my thoughts on Batman and Gotham City one day), but also because that's a fact of life in some places. In the end, for me, this is the reality of the American South, hyper-dramatized and writ larger than life to shock and disturb the delicate Northern city dwellers. There's a way to pull that off that isn't condescending, it just wasn't this.

Themes

In the end, this movie is about familial ties that have been corrupted for whatever reason. Sally ostensibly loves her brother but views him, above most other things, as a burden she bears through life. The father consistently reminds the brothers that he is the one who really cares about and takes care of them. Where would they be without him? No, really, where? The implication is far from anything resembling family, unloved and unwanted and unwelcome.

There's also the whole thing with disability and in particular leaving those who aren't fully able bodied behind until it changes them fundamentally.

Franklin is deeply resentful of his sister and her friends. He's forced to wait, time after time, for someone to physically move him if they aren't on even ground. When Sally has no one else to turn to as all her friends have disappeared, he suggests the most sensible answers in accordance with being wheelchair-bound: go to the local gas station in a working vehicle so they're together and working towards the goal of finding her friends. She refuses, defensively saying she refuses to leave without her boyfriend and only admitting they have no keys (and no escape) when Franklin discovers it. Besides, she says, what if they come back and no one's around? Franklin should obviously be left behind, alone and defenseless and lightless, because he's a burden. When he refuses (I mean, yeah, I would too), she petulantly yells she'll just go into the near blackness of the woods without the flashlight. Franklin knows that would likely be the death of them both (in the Southern sense, not the literal one) and pushes back against it. In the end, she drags him with her. I think this is the only time she has helped to move her brother in the entire movie. He's brutally murdered in front of her by Leatherface.

Leatherface and his brother are hidden away from the world by their father, along with the grandfather, to do the dirtiest work. They bring in the tourists. They do the slaughtering. They do the butchering. They occupy themselves with the ghoulish crafts scattered around the house. They even, if memory serves, do most of the cooking.

Meanwhile, the father pretends he has nothing to do with all the death around him even though he delights in it. He, just like Sally and her friends, can generally walk around without their Otherness being pointed out. At least, you know, until they can't anymore. For instance, Sally, Franklin, and her friends instantly get clocked as out-of-towners by the locals, despite her grandfather's grave being in town (which means the family hasn't been gone long) and Sally and Franklin mentioning visiting and living in the house in childhood. Small towns have long memories and the fact that it seems like no one remembers them feels telling.

I also see what Carol J. Clover means when she says the Final Girl is both victim and hero in Men, Women, and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Especially in older horror and particularly slasher movies, the classic Final Girl only becomes what she absolutely must to survive and not much more. ...I'm probably going to mention this book a lot. It's my current reading for learning how the fuck even does horror work.

Not Pictured: Jerry (the boyfriend).

Yes, I did look up every name but Franklin's.

Narrative

This has the problem other movies before the 80s or so have: its story doesn't fit the modern sense of storytelling and it feels disjointed with massive swathes of the story missing entirely. This isn't, like, a sore point or anything, just a matter of fact about how storytelling in film has changed and evolved over time.

I also definitely did do the thing of questioning their every decision from the start. Why drag along a wheelchair user if you're not going to accommodate him AND the place you're going to can't accommodate him either? Why drive in a van with only two seats total? Why return to a wholly untended property that you have no tools or anything else to tend to? Small towns are always like this (weird and insular) but seriously NO ONE (aside from seemingly the town drunk) had any idea about the murder family? Like mentioned above, these are holes that would be patched with things like dialogue or something in modern film. Sally would likely feign being apologetic while someone else tells the group's true feelings and then not be refuted.

"This was the only thing that could fit his wheelchair." "Yeah, and just about nothing else."

"I couldn't just leave him alone all summer! (Spoken in a stage whisper, of course.)" "You leave him alone the rest of the year, what's the difference? (Spoken at full or near full volume, of course.)"

"I can't remember why we moved, I was really young."

The options go on and on ad nauseam and would probably be said by her friend's boyfriend or her own. Said boyfriend would be chided and maybe giggled at and things would move on without it being called out. None of these are GOOD or NICE things to say, but they would bring more context to the familial relationship (and say a lot about families of the time, in particular that the niceness we see is a thin veneer hiding a lot of human ugliness) that the 70s didn't place any value in yet.

Other Notes

I definitely see what Rob Zombie basically lifted whole cloth and turned into House of 1000 Corpses (2003), just turned up to 11 and with much more of a weird fantasy/supernatural twist at the end.

I think the most interesting tidbit about the movie is that so little actual gore is shown. Almost all of it is implied with screams of agony and hastily applied blood smears. Even Franklin's death, the most personal one shown, is fast cuts made in near darkness with shapes and little else.

The last shot IS beautiful though. True golden hour shit, filled with despair and melancholy.

Also WOW at having a Black man in a truck named Black Maria save the white Final Girl only to be abandoned as soon as someone else shows up with nary a single syllable uttered to the truck driver or from him.

What I Learned

I'll be honest, I don't think I'm gonna get a lot about storytelling (like writing-wise or pacing-wise) from a 70s or even 80s era movie unless that's the kind of story I'm wanting to tell. I can learn a lot about framing and allowing a viewer to fill in the blanks from this movie however. Which, to be clear, is still storytelling. It just focuses more on the visuals, which a writer still has to be able to convey to an artist. As I mentioned above, it's WILD that so little gore is actually shown, yet people often remember it being there and extremely visceral. You don't have to show every drop of blood for it to be a flood. You just have to show enough to convey the point, and enough is going to change a little every time.

Wanna chat about this movie with me? Just reply to this email. Or say something on BlueSky. Or maybe I'll follow through with the TikTok post accompaniment to this and you can respond there. Who can really say!