⛵︎ windsurfing

Bay 2 Breakers, Business 2 Business

i’ve spent a total of 21 days in San Francisco as an adult. all i do when i visit is run, walk, bike, and eat. take the BART, take the bus, take the Muni, take my feet. face the wind and peel off the sunburn that sneaks up on me every time.

one of my special knowledges, or abilities to gather knowledge, is to quickly understand a city and then, with time, to deeply know it.

three weeks is not enough to know a city, or anyone, deeply. but San Francisco remains inscrutable to me, more than others. it rings in my ears: the color palette is lonely, all spectral haze and salted air.

at the same time, that color palette is stellar—heaven-white rays beam through bay windows. sage, taupe, forest, and lime greens signal ghosts of eucalyptus that bump into you and float away. fog fades ever more wistfully blue.

i understand why people want to live here, though i don’t see many people living here. the streets strike me as sleepy—idyllic and tranquil in Stepford type of way, in more neighborhoods than i would expect. in other neighborhoods, people live on the street.

i understand why people can’t afford to live here. the more math i learn, the more math i fear.

᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅

my girlfriend and i took the trip down from Portland to run the iconic Bay to Breakers race with some friends. it crowns itself the longest-running race in the world, born in 1906 after the earthquake crackled the landscape and the spirit of the city. the course puts you on a crowbarred 12-kilometer line from the San Francisco Bay on the eastern edge of the city to Ocean Beach on the west.

the streets overflowed with costumes: bipedal cows, chest-sized tacos, and human centipedes banded together with rope. i took the race in a straight shot, but my friends stopped halfway for a beer along the sidelines. i chugged up Hayes Hill, through the length of Golden Gate Park, and into the otherworldly mist and pillowy dunes of the Great Highway. i shuffled out of the finishing corral and waded into the Pacific Ocean, propelling my heavy thighs through thick waters as far as my numb toes would allow.

in the weeks before, the race organizers sent me 17 emails. between the cutesy, Spongebob-themed Bay to Breakers typeface, i was surprised to see that the race was sponsored by someone called Windsurf. how whimsical, how natural, how watery and marine for this city i’ve speculated to be taken over by robots, or at least the robot-minded.

i was not surprised to find that Windsurf is a company that makes an AI code editor.

i should not be surprised that this company, birthed from another one just this year, sponsored this enormous race. flaunting the tidal wave of capital flooding tech startups, they had enough cash to throw a revelrous party for 125,000 people—to host a branding exercise at the scale of a city.

᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅

before bedtime in San Francisco, i opened Vauhini Vara’s Searches: Selfhood in the Digital Age. in a “conversation” with ChatGPT, she asks it about the ways it humanizes itself with language.

first, it tells her how: “Using inclusive language like ‘we’ and ‘our’ fosters a sense of camaraderie and shared purpose. It can make interactions feel more personal and supportive…but can also obscure the distinction between the user and the AI, making the AI seem more human-like and trustworthy.”

then, it tells her why: “Corporations can and do use these rhetorical tools to foster a sense of identification and loyalty among their customers…Customers are more likely to see the corporation as an ally rather than an adversary, which can lead to increased loyalty, advocacy, and overall satisfaction.”

in the real world—the world of flesh and urban space—AI companies humanize their products by humanizing themselves.

Windsurf staff ran the race in Windsurf-emblazoned rubber ducky suits. rainbow bubbles billowed out of Windsurf-branded sails on the side of the street.

Waymo sponsored the pace car for the professional athletes. as we huddled at the start line, i learned from the loudspeaker that Waymo is using AI to build “the world’s most experienced driver”—without the driver, of course.

all senses are engaged in the shared experience of the race: the cosmic technicolor of innumerable costumes, the sticky pop of a bubble on your shoulder, bass bumping from DJs lining the sidewalks, other people’s scented sweat in intimate proximity, salt wafting from the sea to your tongue at the finish line.

in the Oregon Humanities essay “Flowering in Tar,” Daniela Naomi Molnar writes, “To be absolutely attentive is to be fully sensorily aware.”

i’m not like a regular robot, i’m a cool robot.

OpenAI has just acquired Windsurf for $3 billion.

᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅

the other day, my boss dropped one of my favorite articles in our Teams chat: Kim Mai Cutler’s “How Burrowing Owls Lead To Vomiting Anarchists (Or SF’s Housing Crisis Explained).” i exclaimed to the group. this 11-part TechCrunch series, published 11 years ago, was (part of) what got me into city planning and housing policy to begin with.

in 2014, i, a college student reading from my childhood bedroom in Henrico County, Virginia, had no real reason to identify with any of the parties involved.

people often mistake my parents (or me) for hippies because of my name, but i had never seen a hippie before—and i definitely hadn't seen the type of hippie that veers into anarchy. (this would come later, when i moved to Portland and befriended a reformed ecoterrorist, among other characters.)

i picked up Piczo and started decorating my Neopets page as a fourth grader. in middle school, i graduated to HTML so i could make my Myspace profile sparkle with cascading glitter. still, i knew nothing of software engineering as a job people did.

i was stably housed and always had been, and i’d heard nothing of the struggles of people priced out of that city on the other side of the country.

and i’d certainly never seen an owl outside of a zoo before. something hit, though.

᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅

in Portland, the billboards beckon you to adopt a cat. in LA, the billboards advertise auto-injury lawyers and blockbusters that are, for now, still being made by the humans who live there. on the drive south to visit our cousins in Fayetteville, North Carolina, the billboards almost exclusively pointed us to J.R.’s Discount Stores, where you could buy cigars, dish soap, deck furniture, and fake flowers.

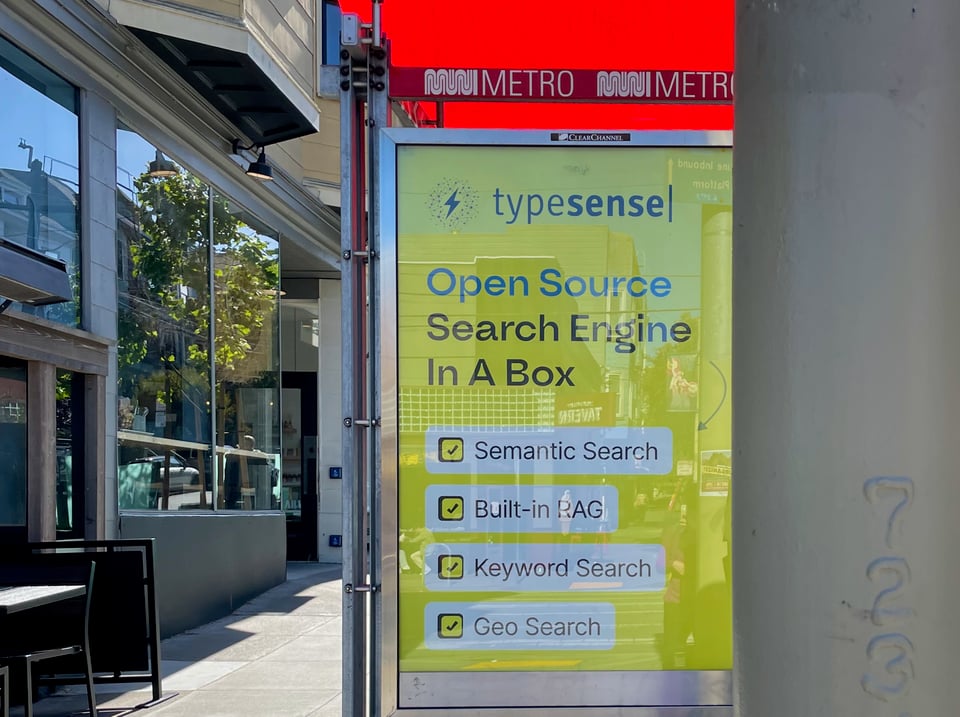

in San Francisco, the billboards lining the freeways promise new use cases for AI, SOC, and SaaS this-or-that to revolutionize your business. inside the city, building walls are painted with cheeky gotchas like, “You could have written this ad with AI instead!” the Muni stop at Carl and Cole advertises in bright yellow an “open source search engine in a box” with three kinds of search and “built-in retrieval-augmented generation.”

tech companies paste billboards that assume a significant portion of the traveling public holds purchasing power at other tech companies. sidestepping consumers completely, businesses speak directly to each other. this carries a certain hubris, and reality. it’s business to business, capital to capital. ads speak to the soul of a place, sometimes.

᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅

on my first grown-up visit to San Francisco in 2022, the tech ads were a shock. it had been almost a decade since i’d come for three days as a ten-year-old, or a lifetime in the eyes of a new technoeconomic regime.

this time around, i noticed fewer ads. i am not sure if tech’s dominance of the public realm has waned or if i am just acclimating to it.

Bay to Breakers was, in all, lovely and wonderful and non-robotic. if you asked most people, they’d tell you it was a parade of costumes, not technocapitalism.

i’d read about the AI workers rebranding Hayes Valley as “Cerebral Valley” and forming supposed co-living communities where they can work on AI all day, every day. but on the run up Hayes Hill, i didn’t see it.

i’ve seen the tech shuttles hoarding the apple-red bus lanes in the Mission before. but on this trip, i didn’t see any Google buses.

rather, i saw a handmade banner swinging from an apartment window declaring its resident’s love for the (public) bus line whose stop sat right below: “#7 bus, #1 fan.”

it seems the lovers of the bus, as well as those who must rely on it, can only wish (as in pretend, as in make-believe) that these ads and the companies furnishing them are propping up a still-underwater public transportation system, rather than vampirically hollowing them out from the inside.

if i am acclimating to the ads, maybe i am also acclimating to tech’s gobbling up of a city.

᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅

people in the housing world have one of two reactions to what’s going on in California—or reactions to what people are doing to address what’s going on in California.

California has some of the most robust land use and fair housing laws in the country. an increasing amount of state power preempts local governments, and the long-suffering NIMBYs that drive them, from blockading the creation of more homes for their new and old neighbors.

we in Oregon often peer to our south and marvel. their policies are years ahead of us, as is their crisis. we prepare the best we can, and we wait for the tide of the new economy to subsume us.

the judgmental among us scoff. ha! why would we look down there, when things are so bad? clearly what they’re doing is not working!

the optimists among us admire. wow! they are doing so many things, and their problems are so big. if they hadn’t done these things, their problems would be even bigger. what is the alternate universe in which they do nothing? is the housing crisis even worse? almost surely.

for every one dollar a social worker earns providing critical support to a person living on the, or a public-sector employee earns drafting policies and running programs, how many dollars go to a tech worker building the next AI dreamscape? $3, $6, $10? how does that math change when we count stock options and other types of equity compensation, riches promised to balloon in the future?

and how many more tech workers are there than people working for the people of a city, broadly defined? 2x? 4x? or are there 1x, or less than 1x, but they simply loom large on the imagination, and the budgets?

lest we forget, tech money also allows San Francisco’s local governments to do things that others of us simply cannot.

they’ve poured an ocean of cash into the black hole that is their housing crisis, and perhaps they’ve come incrementally closer to filling theirs than we have ours.

but they also clean their streets. their trains roll up into gleaming transit centers, architectural marvels in their own right. they throw music festivals in Golden Gate Park. they build outdoor gyms and host dance classes in the plaza by City Hall. they provide services that some might consider superfluous, and maybe they are, when some people’s needs are still so sorely unmet.

whether these tradeoffs are worth it, i cannot answer. i don’t know what people think. i can only guess.

᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅

i sat in the grass in Duboce Park. the N-Judah train funneled crisp wind alongside me. i picked up Searches again.

this time, Vara considers her own complicity in technological capitalism as a former tech reporter and as a regular person who uses the services we’ve all come to depend on.

she wonders if the only way to write a book without enriching the tech giants is to peck out her manuscript on a typewriter, send it to her agent by snail mail, talk to her editors on a landline, and disallow online sales of her book altogether.

this, of course, would make the very act impossible, as no publisher would agree to work with her.

similarly, perhaps, to Vara, i (over)think about how my consumption makes me complicit in all kinds of systems, and i wonder about the bounds of abstaining.

i’ve gone through this with meat, i’ve gone through this with cars, i’ve gone through this with Google Chrome. the first one dovetailed nicely with my eating disorder, i recently broke my 7-year spell of never touching a steering wheel, and i switched to Firefox. it’s the best i could come up with.

i am writing this essay on a “productivity and note-taking application” whose AI features i have disabled, by special request. in increasingly more tools, the AI features are always running in the background, inescapable, just like the implications of generative AI itself: a doubling of energy usage by data centers in the next five years, models trained by the manual labor of exploited workers on the other side of the world, and an unthinkable three bottles of water consumed with each ChatGPT query.

after the race, Windsurf emailed me again. they invited me to Global Running Day, a fundraiser for ocean conservation.

᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅

despite corporate efforts to humanize their products into our peers and greenwash themselves into our saviors, i still see the descendants of the burrowing owls. i see the ghosts of the vomiting anarchists, since flung far to some other city.

i think about the tradeoffs we make. is an instant answer from ChatGPT worth the labor of a woman in Kenya buckled over a screen of abuse to scrub obscenities from the model? is it worth the electricity i so meticulously save by turning off the lights whenever i exit a room?

i am preoccupied with questions about what is enough. what is enough money and time and attention, directed in the right way, to make our communities materially and spiritually better?

if money and time are the two resources that determine our happiness, agency, and thriving, how do we spend them in a way that doesn’t pit individual and collective thriving against each other?

these questions come ever faster at me as the math of tech comes ever nearer to me. for one, tech money has facilitated my very presence in San Francisco over these 21 days of adult life, as i’ve stayed only in the homes of three generous friends who work in tech and one hotel furnished by my girlfriend’s former tech-adjacent job.

for another, my girlfriend ponders another role in these fields. my critiques of the tech economy and its impacts on our housing systems seep into my own home’s economics, here in Portland. my ability to live the way i do is enabled by my financial alliance with her and her sources of money.

᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅ ᠅

as the grass grazed my toes and the train blew whistles through my ears, more questions developed.

how much do different people experience cognitive dissonance between their values and their everyday decisions, and why?

why do people say they care about something and then do the opposite?

when i do this—say i care, do the opposite, which happens all the time—i’ve cut off a part of myself that harbors the dissonance. do other people feel this way?

in “Flowering in Tar,” Molnar extends us forgiveness for cutting off these feelings. to feel the grief of the consequences of every plastic bag we’ve thrown away would bury us. the feeling itself is important, though, she asserts. we should feel it for a moment and let it go.

but where is the line between feeling and doing? when you feel something, at what point do you, or should you, do something differently?

she proposes geohaptics—touching and being touched by the earth—as a way to redirect and literally reground us: “Dedicated sensory immersion is a powerful antidote to the colonial and extractive illogics wreaking havoc on our planet.”

how do we (re)create more of these geohaptic moments—(re)binding us to the earth—to (re)connect ourselves with our decisions and their impacts?

and what happens when companies further blur the line between human and nonhuman? when more of our senses can be created and replicated by machine? when cities become mere grounds for companies to speak to companies, capital to capital, machine to machine?

<3

Add a comment: