☼ inevitability is a myth!

we can be the TRUE Luddite teens

perhaps you’ve heard of the Brooklyn Luddite teens.

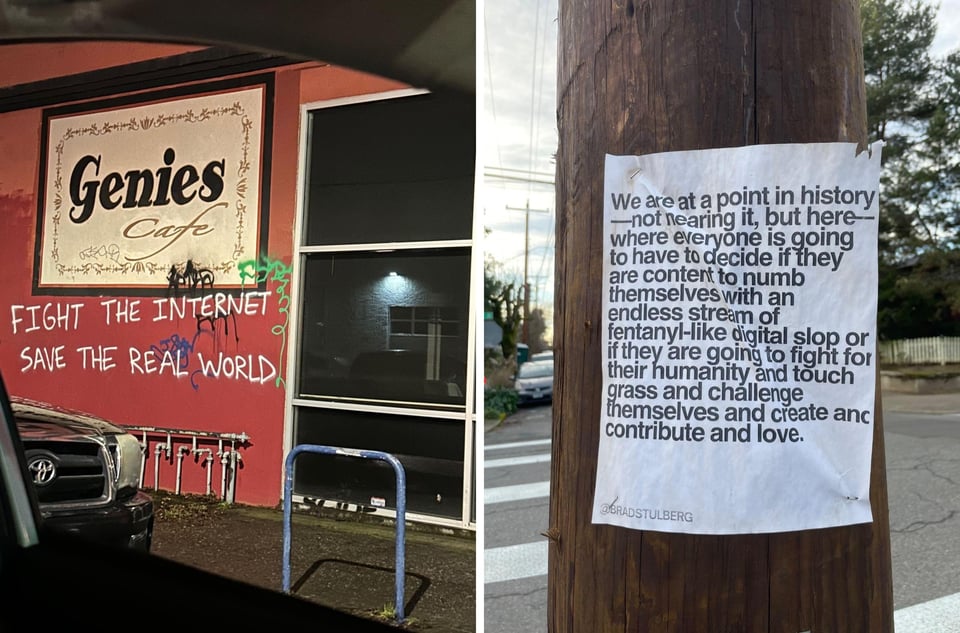

photos show these rare specimens sharing a seat on a boulder, hunched over yellowed paperbacks, or poking at a log with a stick in the woods, not a glassy screen in sight—only scuffed Motorola Razrs from when i was a teen.

the teens have forsaken their phones in service of their own mental health and the political and social future of their country. they started a club that meets every Sunday. “We don’t keep in touch with each other, so you have to show up,” in the flesh, at the park. a dream.

last week, i wrote about the compounding effects of technocapitalist evils on the physical world, our delicate relationships, our fleshy bodies. all of it makes me want to fully drop out, to become a Brooklyn Luddite teen. i want to print out Mapquest directions and call my friends on landlines. more than that, i want to reclaim my mind from the little screen of dizzying lights.

the rebuff is en vogue. as Jasmine Sun noted in her dictionary of today’s Silicon Valley-speak, “Cold-emailing your way into a dream job is pretty high-agency; quitting it to become a strawberry farmer is even more so.”

unfortunately, though, we cannot turn our backs and head off to the meadow, or to Prospect Park, as it were. we are bound up in these digital systems. in city planning, at our best, we care about people and the planet. the way our technologies are currently owned and operated threaten both.

the only way to solve any of the issues we care about (racism, homelessness, climate catastrophe, abhorrent wealth inequality, the rightward political turn much of the globe seems to be taking, the collapse of political processes and systems…pick your least favorite) will, at this point, involve using these tools (among many other tactics).

floating above everything else, like wispy cirrus clouds in the high atmosphere, is our digital infrastructure.

❃ ❃ ❃ ❃ ❃

little watermelons crop up all over Instagram. pro-Palestine organizers have had to develop a new language, an “algospeak” that spells in code to throw off the classification systems that suppress them. they make accounts on all possible platforms and backup accounts for those accounts, cross-posting into a funhouse mirror.

they do this to get around collusive offensives by companies and governments to block communication. Human Rights Watch found that Facebook and Instagram systematically censor Palestine-related information by removing posts and comments, suspending and disabling accounts, shadowbanning, and other tactics.

Waging Nonviolence notes that Meta built an automated “hostile speech classifier” for Arabic content, and in Gaza and the occupied West Bank, “Meta’s automated moderation tools needed only an AI confidence threshold of as low as 25 percent to remove content.” Meta reviews Hebrew content on a less frequent, “more manual case-by-case basis.”

Meta then had to apologize for “accidentally” auto-adding the word “terrorist” to people’s Instagram bios that contained the words “praise be to god” or “Palestinian” or the Palestinian flag, blaming it on “a bug.” Meta and other companies draw on lists of “terrorist countries” from the U.S. State Department to write these policies.

in its first week of existence, American-owned TikTok joined in. CEO Adam Presser bragged onstage about flagging the word Zionist: you can use it if “you’re a proud Zionist,” but “if you’re calling somebody a Zionist as a dirty name, that gets designated as hate speech" to be suppressed. two dozen Jewish organizations “constantly feed” TikTok “intelligence” and alert them to “violative trends.” no Palestinian organizations do.

once a critical source of information about life and death in Palestine, TikTok has entered the warm embrace of Trump-dictated censorship.

the digital spills into the physical (San Francisco, dangerously close to Cerebral Valley)

❃ ❃ ❃ ❃ ❃

when people do find a way around algorithmic suppression, the results can be revolutionary. social media allowed the Arab Spring to happen. protests organized on Facebook brought people from digital space into physical space.

Taylor Lorenz called social media a revolution, but, as W. David Marx notes in Blank Space: A Cultural History of the Twenty-First Century, we cannot mistake the revolutionary capabilities of the internet for revolution itself. he notes that “a true revolution involves a reversal of status—one in which outsiders don’t just bypass gatekeepers but seize control of the establishment.”

Twitter once helped people build movements. then Elon Musk bought it and revealed to us just how much power we don’t have. now, he has more dollars than there are total words living on the internet, at ~670 billion vs. 630 billion.

continued roller coasters of algorithmic suppression—thwarted only by creating new languages and backdoor channels—show that people have not yet seized control of the technocapitalist establishment, or the means of communication.

controlling the means of communication is only the first step toward a reversal of status in halls of power—words on the page of legislation, bodies in voting booths. only then can we see a material revolution in physical space.

the Arab Spring, not the internet, was the revolution.

❃ ❃ ❃ ❃ ❃

every time i open up my State-issued laptop, i’m served cute, pleading factoids. “Scientists are using AI to map the bottom of the ocean!” i choked through a mandatory AI training that directed me, a government employee, to summarize my public comments with ChatGPT. i’ve felt pushed—a gentle nudge, or pinpointed pressure—to adopt generative AI in its various forms. surely you have, too.

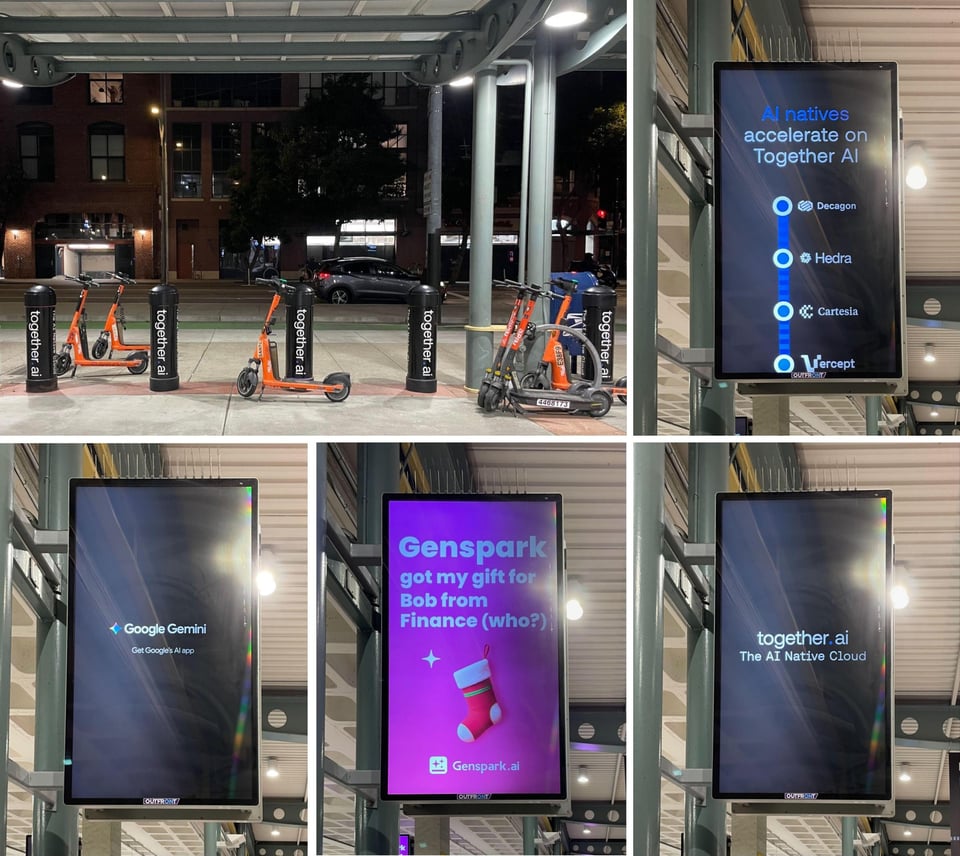

in the CalTrain station, one must wonder whether this AI ad revenue is what allowed for the purchase of sparkling new, double-decker electric trains with wifi, tables, and kingly bathrooms

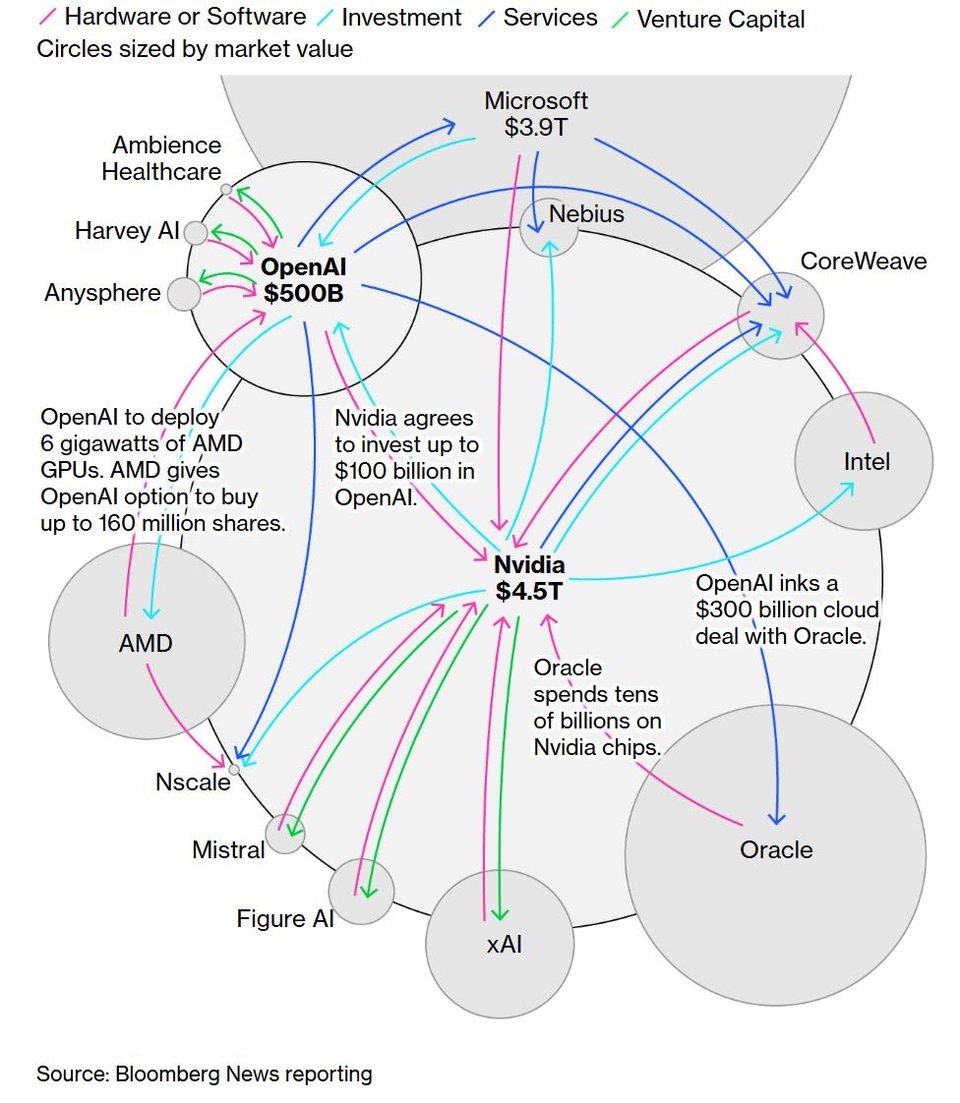

AI companies sell us on inevitability with a hope edging on fear: there’s a future in which we’ll get to work less, and there’s one in which we won’t be able to work at all. this inevitability is core to their business model, because they’ve tied up hundreds of billions of dollars in a financial circle-jerk of epic proportions.

Cory Doctorow observes that “Seven AI companies currently account for more than a third of the stock market, and they endlessly pass around the same $100 billion IOU.” AI investment accounted for 40 percent of the U.S. GDP and 80 percent of stock market gains last year, and it outweighed all consumer spending combined—that is, all the real things that real people buy. basically, AI is doing subprime mortgages now, and it’s threatening to blow up the economy at the scale of the 2008 financial crisis.

to avoid bursting the bubble they’ve blown, this handful of companies needs people to become reliant on their tools.

press deeper, and inevitability lies at the core of their ideology. sociologist Ruha Benjamin, quoting philosopher Émile P. Torres, writes, “a key tenet of the artificial intelligentsia’s gospel is inevitability, their own version of predestination…one way to understand the worship of AI is as a religion for atheists: ‘since God does not exist, why not just create him?’”

so, we hear it (or say it) all the time: “the technology is coming, it’s here, so we might as well make sure we do it well.” it’s a comfortable position for those whose careers have landed them in the middle of the arena, and it’s understandable. but it’s not true.

these tools are not inevitable—rather, they’re being foisted upon us. companies force demand by fabricating it, and fabrications will always unravel. by September of last year, use of generative AI had already declined at large companies, and people are starting to see “social” media for what it is.

❃ ❃ ❃ ❃ ❃

there’s nothing quite so dizzying as peering over your partner's shoulder as they click to their Instagram Explore page. you may find that their lush inner world has been reduced (not unpleasantly) to cats loafing on top of glass tables and red-panda wildlife photography. they may find you (deeply unpleasantly) pigeonholed into running workouts and acrid cottage-cheese “ice cream.”

Facebook’s original mission was to “connect the world.” now, the vast majority of what people see across Facebook and Instagram, as well as TikTok, comes from strangers: influencers and advertisers who stand to make a buck from algorithmically assisted virality. in its arms race with TikTok, Meta has moved fast to break itself, transforming into a TV show of strangers’ videos.

tech reporter John Herrman describes this turn as “platform desocialization,” a 180-degree shift from “platforms full of people seeing things mostly on purpose to platforms full of people seeing things mostly because an algorithm thinks they might engage with them.“

we’ve left behind a social media of family and friends, and even parasocial media relationships with people we’ve listened to over time. now, we’ve reached a fully desocialized media—and one where we don’t choose who, or what, we see.

Berkeley researchers describe how the recommendation-based architectures of Instagram’s Explore and TikTok narrow the funnel of what we see. they sink us deeper and deeper into niches supposedly attuned to our own hyper-individualized taste profile—your red pandas, my toxic recipes. the researchers attest that discovery—at the hand of our own agency—widens the scope of what we perceive.

❃ ❃ ❃ ❃ ❃

like the hole in the ozone layer and acid rain, we have to believe we can fix our digital environment. smart people are proposing and predicting different futures, both on and off the internet.

in The Internet Con: How to Seize the Means of Computation, Doctorow locates the solution in interoperability, or requiring technologies to be able to operate with each other. this means letting us break out of walled gardens and port our information to other places—to connect with your Facebook friends on a new online community, or cross-upload your photos on three different platforms. this defuses the trap of network effects, or everyone being in one place, and lowers the prohibitively high switching costs, which in turn lets us choose other platforms. monopoly power, eroded!

Wikipedia seems to be leaning into its human-created nature instead of racing into the AI hype like the rest of the internet. it proactively created a policy that lets editors auto-delete AI-generated articles.

the Berkeley researchers contrast Wikipedia with Instagram’s Explore page. in the former, you click from link to link and let your curiosity guide you toward your next choice of what to learn about. in the latter, you open the fire hose to whatever hyper-stimulating gruel the algorithmic overlords wish to serve you that day, making no decisions about where to go. it’s immediate, unceasing, and smooth, where navigating Wikipedia is slower, more methodical, less attractive, but more deeply engaging.

accordingly, some technologists have “reframed friction and slowness not as a usability flaw, but as a feature” of web design with advantages: “resisting ease or efficiency can deepen engagement and add depth and texture to interactions.”

❃ ❃ ❃ ❃ ❃

offline, friction is trending right now. people are realizing that tech companies have created in us a need for frictionlessness. that aversion to friction—to anything inconvenient, new, difficult, or simply requiring effort—spills out to other parts of our lives as well.

Kathryn Jezer-Morton describes it: “Tech companies are succeeding in making us think of life itself as inconvenient and something to be continuously escaping from...Reading is boring; talking is awkward; moving is tiring; leaving the house is daunting. Thinking is hard. Interacting with strangers is scary. Risking an unexpected reaction from someone isn’t worth it. Speaking at all—overrated. These are all frictions that we can now eliminate, easily, and we do.”

she’s vowed to a year of “friction-maxxing” (in the parlance of the very-online), which she outlines as not just reducing your screen time, but (re)building your “tolerance for ‘inconvenience,’” which is really just a misnomer for the daily actions and interactions required to live among other people.

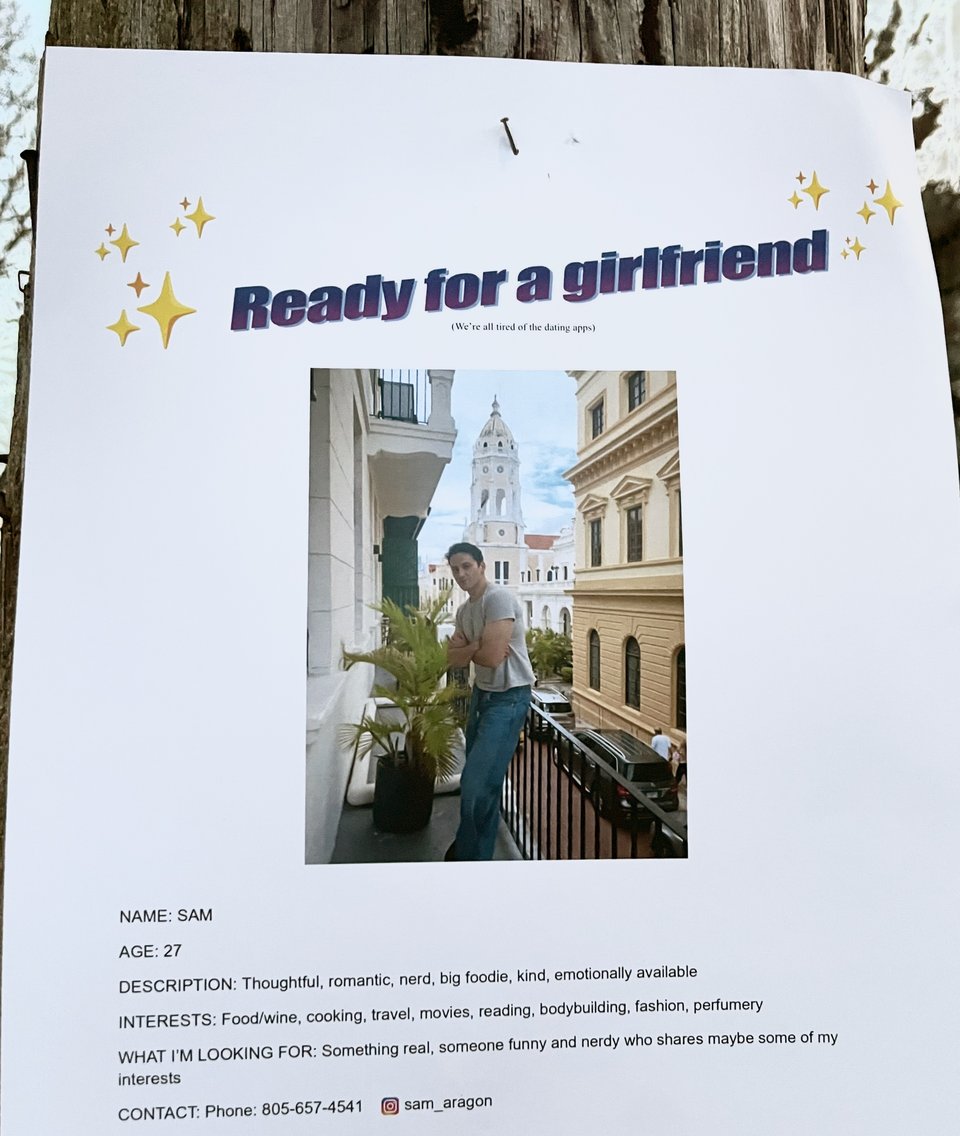

in fact, being offline is beginning to trend in a way that could crest into a new-old way of being. the youth are returning to physical media, hosting record-listening parties and buying up their favorite video games on disks, wise to the reality that the streamers could remove them at any time. we have realized the dating apps actually do want us to remain there, rather than find our one (or multiple) true love(s). zines are resurgent. functions that had been siphoned onto apps are bleeding back into physical space.

J Wortham envisions being performatively offline, but not in a bad way, and not in a fleeting one: “something more conscious and iron-willed than a planned break, something more tactical. Strategic. Refusing to be tracked; refusing to be known, refusing to let our nervous systems get hijacked. Refusing to give all our shit up to AI, and refusing to succumb to the way social media has become a stand-in for reality.”

in SSENSE Wortham predicts that documenting everything will come to be seen as “really tacky” as people organize pointedly “screenless hangs.” they see this as “the new ‘clean’ aesthetic” that serves as “a direct response to surveillance and the influencer economy taking over public spaces.”

professor and cyberethnographer (!) Ruby Justice Thelot positions 2026 as a return to a medieval social life centered on time spent in shared space: “group chats will turn into guilds and our oral-first world will push us to share more physical space with one another, as we lose trust in all things digital.” clubs are back. we're doing crafts at the mall.

Chris Gayomali thinks this year will see scrolling demoted to vice, like vaping, and that “in an attempt to mitigate brainrot” we should “expect an appetite for more satisfying, longer forms of consumption.” he sees us turning from short-form video and AI slop to long-form essays and books “that make our smooth brains work a little harder.”

elsewhere, he too predicts a return to physical space: “a premium on ‘proof of reality’ as a form of brand cachet…live experiences and other signals that can’t be easily mimicked.”

❃ ❃ ❃ ❃ ❃

in order to achieve the material reversal of status W. David Marx describes, we have to believe there is a better way to organize our digital infrastructure, even while we still use it. the handful of men running this handful of companies want us to believe there is no better way.

the first step is turning away from the tech oligarchy—perhaps an easier sell for people who’ve already (tried to) defect from oligarchies in other industries. once you learn that Driscoll’s physically and financially abuses the farmworkers that grow its raspberries, that Johnson & Johnson left asbestos in their baby powder because it was cheaper, that GrubHub tanked small restaurants by making fake websites for them and capturing their orders, that Amazon works its warehouse contractors to the point of literal, visceral death—once you know all this, it’s easy to understand that tech companies would act just as awfully.

turning against the oligarchy is not the same as turning against technology altogether. while the Brooklyn Luddite teens have eschewed their phones and social media, TRUE Luddism is something different, and something bigger. rather than a “simple technophobia,” the Luddite movement, borne of textile workers protesting the obsolescence forced upon them by machinery, “was not against machines in themselves, but against the industrial society…of which machines were the chief weapon.”

like true Luddites, we can turn against the way our (techno)industrial society is organized—who holds capital, power, agency, and dignity. rather than offloading our choices to math equations designed by those who extract from us, may we resist outsourcing our decision-making. then, we can come up with ways to make the digital and physical spaces we share better, and in turn, better care for the people in them.

❃ ❃ ❃ ❃ ❃

if you read this far, send me your address and i’ll send you one of Shay Mirk’s fantastic holographic WE MAKE THE FUTURE stickers 🩶

one day, i will share some tiny tactics for disentangling!

for now, just as our technological landscape is not inevitable, neither is our political landscape, current hellhole it may be. people are practicing new ways of being every day.

what else do you want us to remember is NOT inevitable???

taking a poll,

<3

Add a comment: