The Ship That Died

A story about a story

Sometimes, things stick with you less because of the thing itself and more because of its context. You might think about Monet’s paintings because you learned that his eyesight deteriorated later in life, perhaps The Lord of the Rings movies won’t leave your head after watching hours of behind-the-scenes documentaries, or maybe you reminisce about Minecraft because of the now-distant friend you used to play it with.

This is something sort of like that. This is a story about “The Ship That Died,” a short story by John Gilbert published in 1917.

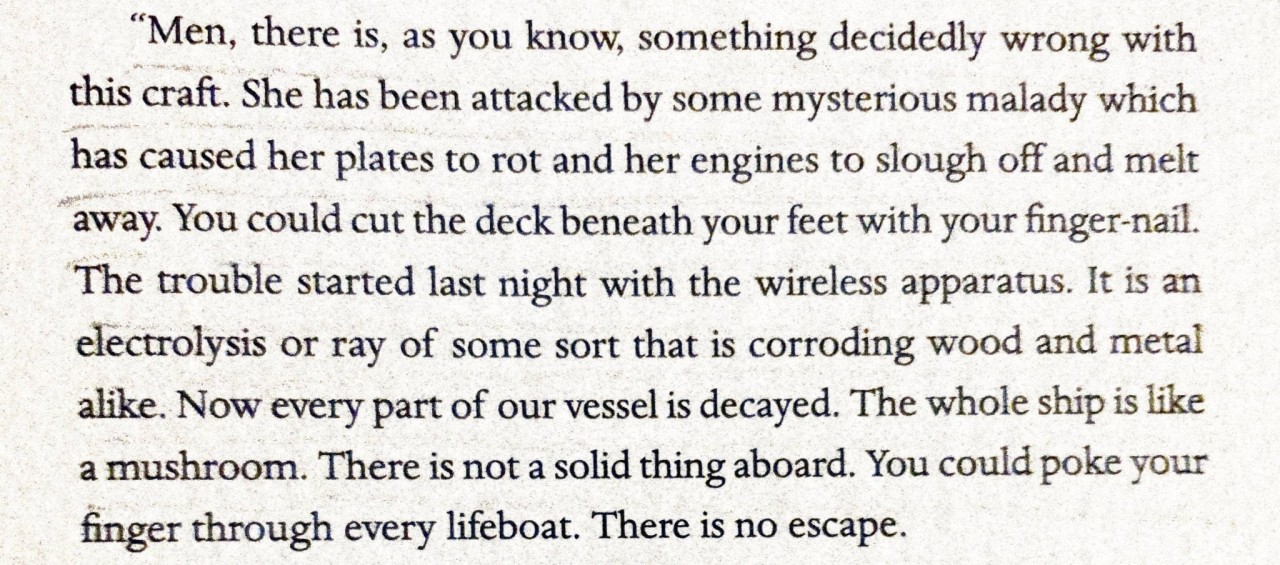

I was first exposed to “The Ship That Died” by a quote that I encountered on social media a while ago:

There’s something so magnetic about this quote for me. The ship is considered an organic being — a fungal, rotting thing infected with some illness. “There is not a solid thing aboard,” the speaker says. “There is no escape.”

Of course, I wanted to know more.

This story and its author proved difficult to pin down, with everything buried under other “Ships That Died” and other John Gilberts.

There’s The Ship That Died (a short film, unrelated to the story in question) and The Ship That Died of Shame (a film based on a short story of the same name by Nicholas Montserrat). There’s John Gilbert, a silent film star; John Gilbert, an author who wrote sports books; and John Gilbert, an insurance lawyer.

But after some digging, I found the story most readily available as a $1.43 audiobook. The description reads:

There have been reports of a phantom ship attempting to run down other vessels on the waters. It is said to be a cutter that went missing, along with its crew. A ship eventually stumbles across the missing cutter, a final log from those on board shedding light on the fate of the cutter.

At this point, I could get the short story, listen to it, and finally be at peace. But then I started to wonder about John Gilbert… What else has he written? Why couldn’t I seem to find anything about this John Gilbert?

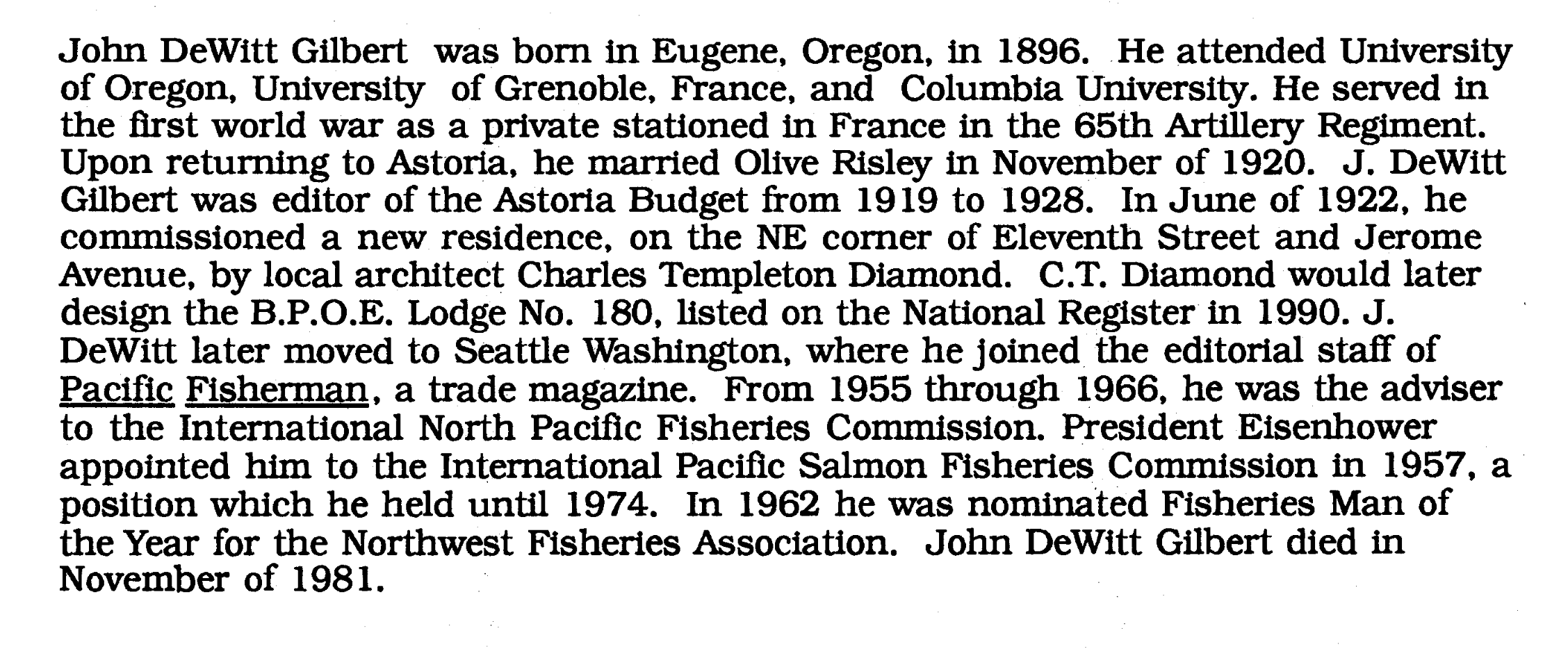

During my search for “The Ship That Died,” I stumbled upon its page in the Internet Speculative Fiction Database and found the author listed as John DeWitt Gilbert. His author page lists his birth and death dates, his birthplace, and links to pages from Find a Grave and FamilySearch.

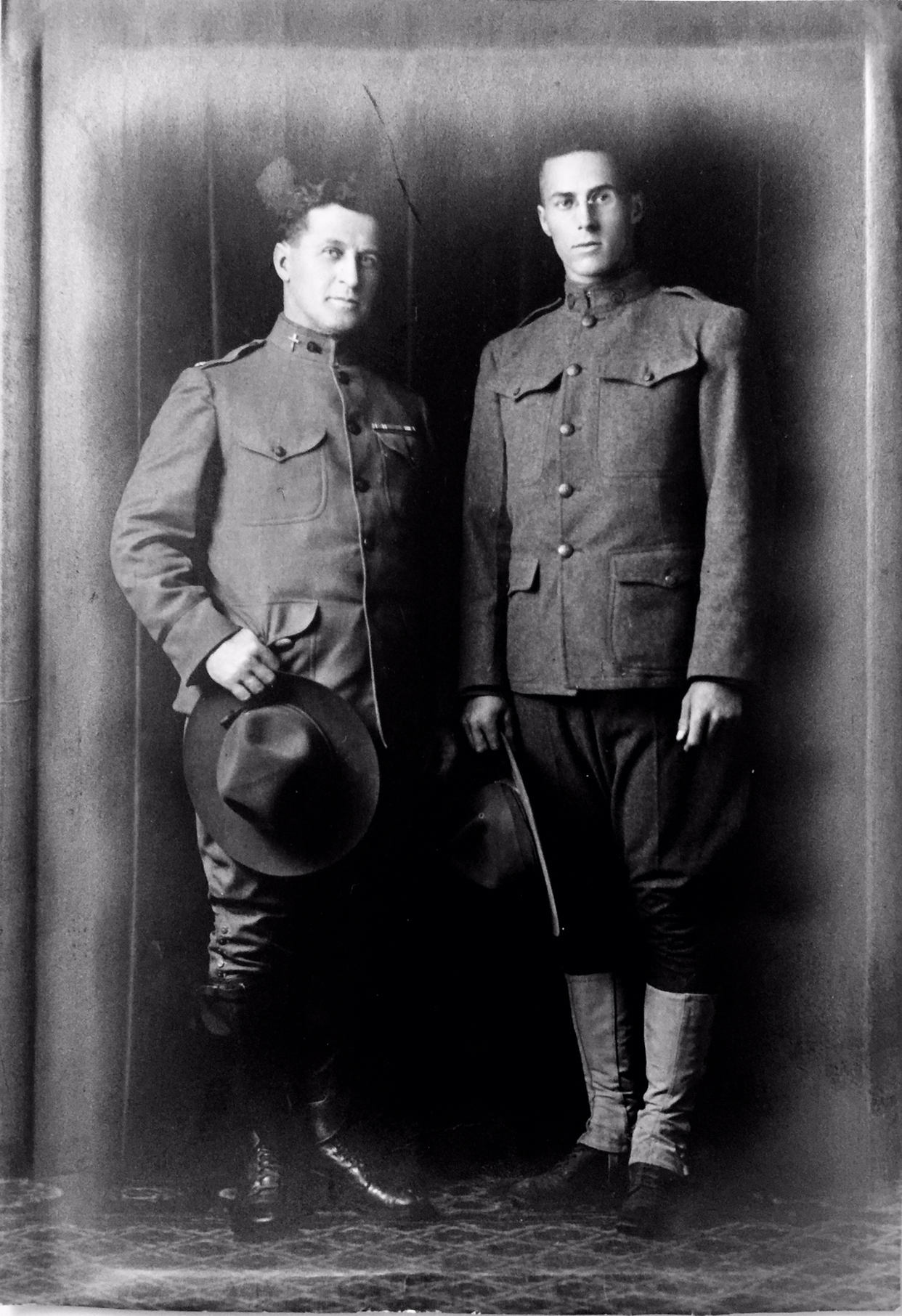

From the FamilySearch page, I learned a bit more: his father was a reverend, he served in World War I, he had at least one son.

Because I now had Gilbert’s middle name, I was even able to find a document from the National Park Service about his childhood home. This document has pages and pages of information about the house, including an 8-page “Statement of Significance” detailing the history of the house and its inhabitants. John DeWitt Gilbert is afforded one paragraph:

This is much more detailed than I’d hoped, or even wanted, to find. But I still hadn’t seen anything about his writing and found the lack of mention almost unsettling. At least one of his stories survived for over a century after it was first published, yet somehow it’s not worth noting?

Finally, I decided it was time to listen to “The Ship That Died.”

In a quick biography of Gilbert before the story, the editor mentions that this is the only story that he knows of by this author. It’s the only one I’ve been able to find, too.

I’m not going to get into the story (I think it’s worth checking out for yourself), though I couldn’t help but feel like something was haunting it — not the phantom ship or its lost crew, but Gilbert himself. The fleeting ghost of a writer lost to obscurity, whom I’d come to know pretty well through my research.

I can’t claim to know how he wanted to be remembered — if he dreamt of being a famous author, or was perfectly happy with being slowly lost to time — but I wonder what Gilbert imagined his legacy would be. I wonder if he thought it would include this story.

“The Ship That Died” was most recently published as part of the British Library’s Tales of the Weird series, which collects a wide variety of strange short-form fiction. It was included in From the Depths and Other Strange Tales of the Sea, a collection of short stories edited by Mike Ashley and published in 2019. The stories are described as being “recovered from obscurity for the 21st century.” But “The Ship That Died” isn’t the only thing that has been recovered, it’s a part of John DeWitt Gilbert that might have otherwise been lost.

I went to the book’s Goodreads page and took a look at reviews (which is almost always a bad idea unless you want to witness some of the worst opinions you’ve ever seen). Predictably, reviewers didn’t seem particularly wowed by “The Ship That Died.” All of the ones I saw that mentioned the story went something like this:

Unlike most Goodreads reviewers, “The Ship That Died” has stuck with me. Partially because I enjoyed the story and just can’t get over some of its descriptions, but mostly because of John DeWitt Gilbert. I can’t take this story for granted now — I see how inexplicable it is that I even know it exists, much less had the chance to read it.

If you go read “The Ship That Died,” I hope you see a story there worth much more than 1.5 stars.

Notes:

Gilbert might have written the lyrics to the University of Oregon fight song, “Mighty Oregon.” I can’t confirm it was him, but according to the school’s newspaper, the lyrics were written by “sophomore journalism student DeWitt Gilbert” in 1916 and the timing seems to work out.

Gilbert was 21 when “The Ship That Died” was first published in the American pulp magazine The Argosy.

If you want to see Gilbert’s childhood home (from that document I mentioned), there are a bunch of pictures on Zillow.

Suggested reading:

The Anthropocene Reviewed is a podcast (and book) by John Green.

“Artifacts of a Doomed Expedition” is an article by Leanne Shapton for The New York Times about various artifacts from the ill-fated Franklin Expedition and the stories they tell. This one’s a more tenuous connection, but it’s a good article nonetheless!

“The Future of Writing About Games” is a video essay by Jacob Geller that talks about how engaging with writing about games can shape your experience with them.