We made our metal trash heap bed. And now, to lie in it.

Every derelict satellite, battered fragment of spacecraft, and random metal shard of debris that has ever been shot into space from Earth is still floating up there right now. Or, not floating. Rather, they’re barreling toward each other at 20 to 40 times the speed of a bullet and colliding, making more and smaller fragments to speed away toward their next collision.

Back in the seventies, Donald Kessler and Burton G. Cour-Palais published a theory on space junk. Every launch creates new debris, and the Kessler Syndrome maths out the point at which the existing debris will explode and create more even debris faster than we can through our launches. And the smaller it gets, the more dangerous and hard to remove. Space junk has the potential to collide with active satellites we rely on for our internet and weather reports — not to mention the earthly implications.

Space junk popped up in the news recently when one piece of derelict machinery fell back down to earth — a SpaceX Starlink satellite plopped on a Kenyan village this January. Fears arose among scientists that even more cosmic trash would collide into the earth asteroid-style.

There’s something hubris-y about it. We did this. We littered on a cosmic scale. And we can’t even destroy it. We have to do it carefully, and expensively, which is not what we do best.

Space junk is also throwing a wrench in the success of future space travel. We have to navigate the trash halo when we travel into space, which is much more difficult, expensive, and dangerous.

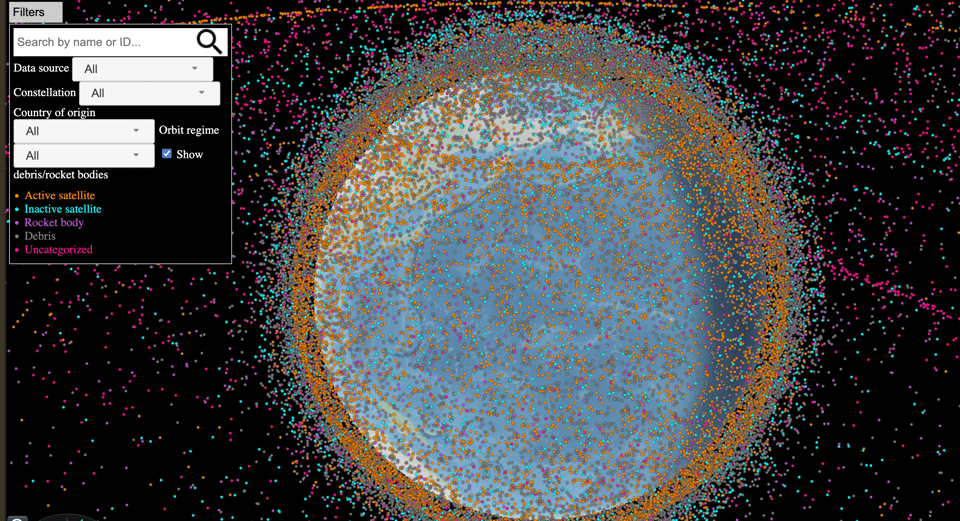

The following images are screencaps of the UT Austin Astriagraph, depicting low earth orbit without, and then with the trash halo of space debris.

Imagine a scene from Season 2, episode 6 of Star Trek: The Original Series in which Captain Kirk navigates the enterprise into what looks like an asteroid belt of machine parts; remnants of a cosmic war. The crew bobs and weaves through wreckage on a high-stakes mission. It is a bit like our own Saturn’s rings, only instead of sheets of ice, it’s our steel carcasses and machine rejects. It is like a cage of spare parts we’ve tried to ignore for seventy years. And now, we’re starting to lose the ability to look away.

But it is also like a museum. The space race propelled us to generate a lot of the junk. Sputnik 1, with the technological sophistication of a can opener was the first thing humans ever sent into the cosmos, and we can still see parts of it up there with its descendants, our internet satellites and modern tech.

Space junk constitutes a real issue for those of us with a deep and burning curiosity about what the universe holds, and it’s not a blameless situation. Kessler warned us back in the seventies. Passion for exploration isn’t the only culprit. Not when the key to the equation is venture capitalists who see cool space rocks as a carbon sphere of dollar signs, something to wack repeatedly until a bunch of smaller, cooler, more expensive space rocks fall out. Article II of the UN Outer Space Treaty says “Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.” It applies only to nations. Not individuals, or corporations. My dream of being adopted into Martian society and working my way up to trusted advisor in their Martian high court was probably doomed from the start, by billionaires who care more for marketing space as a thing to be sold than a mystery to unravel.

And yet, the pure-hearted passion for exploration is still there, along with the billionaires and the mining and the cosmic peacocking for global standing. Every piece of trash is proof that a crew of humans at one point in time slapped fiberglass to steel, hurled it into the cosmos, and succeeded.

I’m not quite sure where to leave this. I deeply want the rich to treat the Earth with care. And I deeply want to see what the universe has to offer, but it looks like the Martians may have to wait. Removing space junk is not a simple task, and as of now, the main support beam for removal is reentry: Earth is slowly pulling the material back into its atmosphere from orbit. Like a good mother, it’s pulling its children back home, albeit slowly, and naturally fixing the problems caused by silly, careless humans.

At this point, no one really knows how or when the issue of space trash will be rectified. But there’s comfort in knowing that while we struggle, the Earth seems naturally inclined to stand by our side. It also appears that the billionaires are stuck with us here on Earth for the time being. Perhaps we can teach them a lesson or two about litter.

Reading List 📚

✎ᝰ. A Half-Ton Piece of Space Junk Falls Onto a Village in Kenya, New York Times

✎ᝰ. Star Trek: The Original Series, Season Two Episode 6, “The Doomsday Machine,”

✎ᝰ. Gravity, 2013 film

✎ᝰ. The Sixth Extinction, Elizabeth Kolbert

✎ᝰ. This is Water, (a speech available on youtube, 22 mins long) by David Foster Wallace