Red Bull doesn't give you wings. Insomnia might.

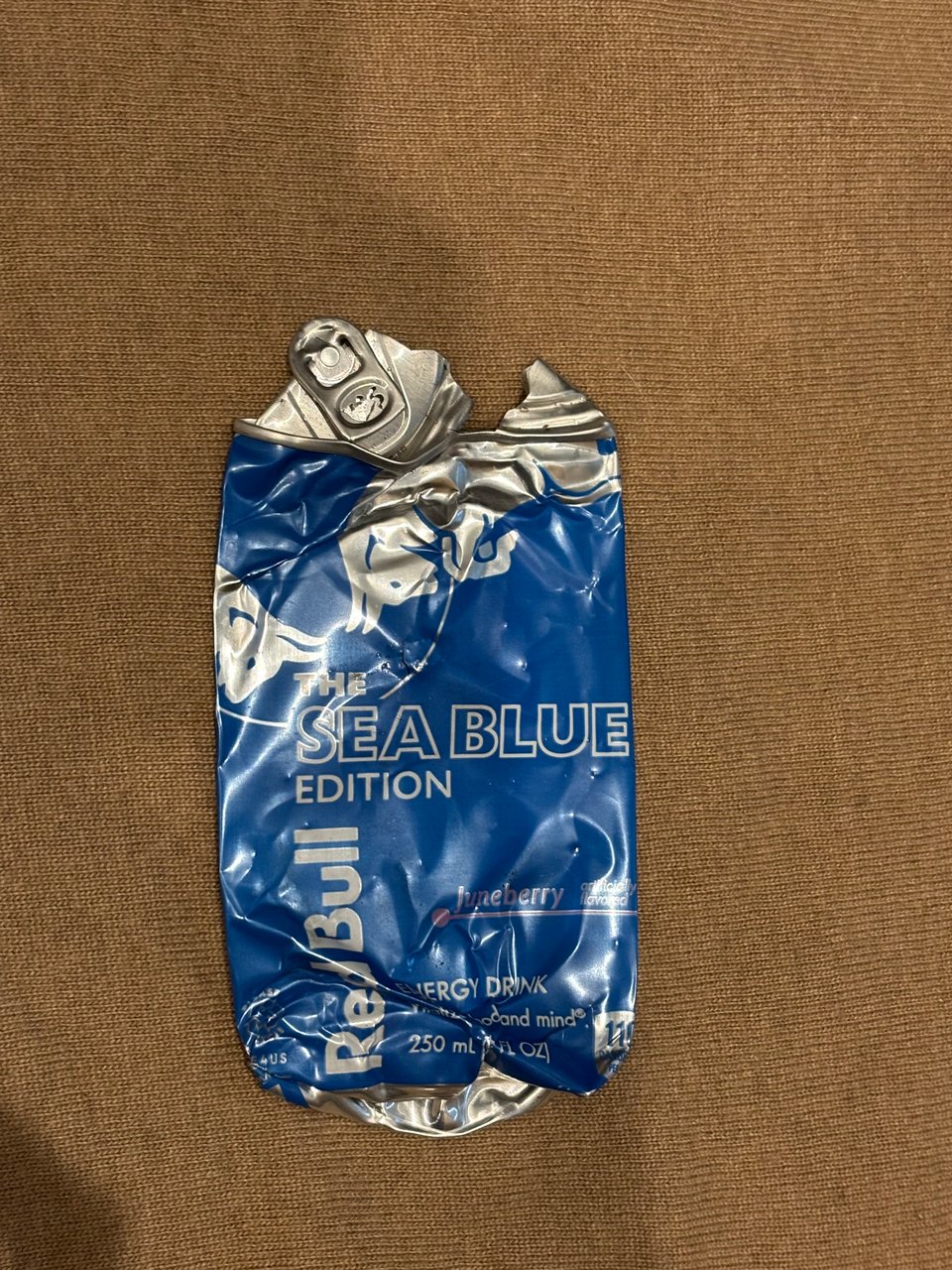

Flattened aluminium, 16x8 cm

Date: c. 2020s, East Village, NYC

Provenance: Recovered from refuse

In 2014, plaintiff Ben Careathers sued Red Bull for false advertising, claiming the slogan “Red Bull gives you wings” is misleading. The internet memed this to death; what sort of idiot would actually think Red Bull gives you wings?

No sort of idiot did, it turns out. Contrary to popular meme opinions, Ben Careather didn’t actually think Red Bull would cause him to grow wings, the false advertising in question was related to the energy, and the implication that Red Bull somehow enhances one’s performance abilities. Red Bull embraced this idea in their marketing, which supposedly led consumers to believe that their product had some sort of exceptional caffeine content or energy-boosting electrolytes. In reality, Red Bull has less caffeine than a cup of coffee. The court ruled in favor of Careather and he got 13 Million out of the ordeal.

Careather was a nighttime security guard. Picture him dead on his feet six hours into a shift, delirious, gripping that can of Red Bull like it’s his sole tether to this plane of reality — as a fellow night owl, I’m inclined to defend him against the internet trolls.

When I was a kid, I heard about a lawsuit against Monster Energy, something about five people having died of heart complications. I was outraged, and I wailed about it to my father, a loyal energy drink connoisseur. How can you drink that stuff? It’s killed people! (I was eight.)

He told me I’d understand when I got to college, when I would start having to pull all-nighters. He told me it used to be his favorite time; something about it being peaceful, solitary,. Being the only one up, it felt kinda mystical and forbidden. Unfortunately, I did understand when I got to college.

The western literary tradition hails the early hours of the night as a corrupting force; a space beyond rationality, when we are closest to madness. Djuna Barnes’ Nigthwood is one example. Dr. Jekyll’s domain is the daylight hours, Jekyll comes out at night.

Romanian author Emil Cioran wrote about his insomnia in his deeply pessimistic The Trouble with Being Born, in which he meditates on birth as a catastrophic event, which necessarily propels forth every other misfortune in life. He was notoriously fun at parties. If anyone needs to be kept away from Red Bull at all costs, it’s Emil Cioran.

He writes about nighttime as a period when thoughts flow uninhibited, and we are confronted with the realities of life and meaninglessness. Morning is when we slip back into rhythms of normalcy and distraction from all that stuff. For the introspective insomniac, nighttime is a “crucifixion,” according to Cioran. But it is also freedom.

“Here on the coast of Normandy, at this hour of the morning, I needed no one. The very gulls’ presence bothered me: I drove them off with stones. And hearing their supernatural shrieks, I realized that that was just what I wanted, that only the Sinister could soothe me, and that it was for such a confrontation that I had got up before dawn.”

Insomniacs like Emil Cioran, my father, and myself tend to view the night as something belonging to oneself. Cioran wanted solitude; he saw the hours in which he stayed up and contemplated as his moment to walk the earth alone. The world was asleep, and the path on which he walked, the view of the ocean, the ground, the bench on which he sat — those were all special for him. And when the geese encroached on his “me-time,” he was reminded that we have to share the world.

Likewise, my days often feel like somebody else’s property. If I’m not in class, I’m on the phone mediating conflicts between my family members. Or I’m editing my friend’s history paper. Mostly, I’m studying. Even when I’m procrastinating, it feels like someone else’s “me-time” I’m wasting. And when the clock strikes midnight and I still have an exam to prepare for, the carriage turns back into a pumpkin and I’m confronted with the reality that there literally aren’t enough hours in the day.

But I have a cheat code for this sticky situation: if I cut out sleep entirely, there are six to seven extra hours I can use. I’ll come to class prepared with notes. I’ll catch up on all my late work. Then maybe, I’ll even get an hour or two to finally listen to my audiobook.

All-nighters hardly ever manifest themselves the way I plan them in my head. Turns out humans need sleep to function, or something. But the correlation between insomnia and being suffocatingly time-poor persists.

There is also evidence to suggest New Yorkers in particular are the time-poorest insomniacs of them all. A sleep study revealed New York gets an average of six hours and thirty-six minutes of sleep per night, which is apparently suboptimal. Our poverty rates are almost twice the national average, and our high cost of living has many New Yorkers working extended hours or multiple jobs. Maybe that’s the real reason our city never sleeps.

Reading List:

Emil Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

Djuna Barnes, Nightwood

Fyodor Dostoevsky, White Nights

The Atlantic, Red Bull Is Just Soda