Beethoven in mythology: the conversation books, and the composer’s need to be understood

Clearly, I’m playing fast and loose with my definition of “discarded material.” This week’s update is on Beethoven’s lesser known creations: his notebooks, The ones that survived, at least. And it’s long form — I will take no personal offense from those who choose to skim, or wait for next week’s regularly scheduled and non-historical pile of trash. For now, let’s hope it’s worth the scroll.

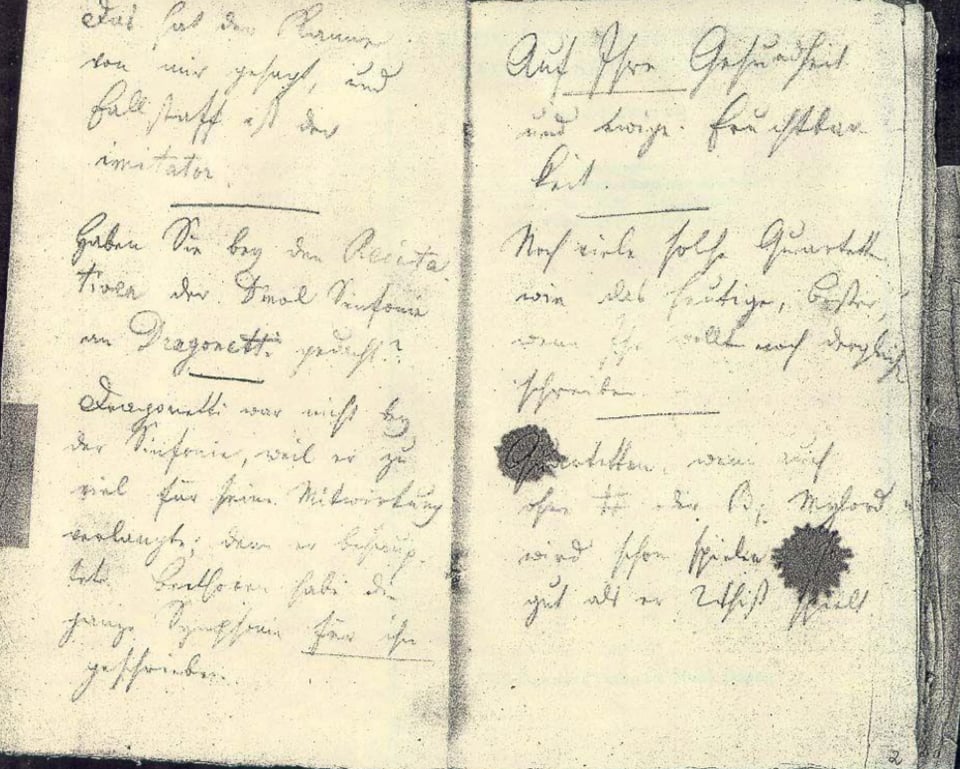

Ludwig Van Beethoven was not known for his writing. Nor should he have been — it was a hot mess. But he did, in fact, write. Toward the end of his life, that’s all he did play piano, drink, scrawl down every mundane detail of his day, eat an entire duck for dinner by himself, scrawl down something existential and deeply concerning, try and fail to sleep, repeat. As his deafness grew, Beethoven used his “conversation books” to help him communicate. They were regular notebooks in which his few loved ones, students, waiters, and doctor would write their side of the conversation for him, and he would respond orally in German. At first, the conversation notebooks read like a one-sided telephone conversation — until the end of Heft (notebook) 3, in which we start to hear his voice.

After his death in 1827, Beethoven’s assistant Anton Schindler destroyed and fiddled with almost two-thirds of the conversation books. 139 of the notebooks have been salvaged and there were said to be around 400-500, around 10k total pages. Volume-wise, that’s roughly 6.5 thousand pages of Beethoven’s chicken scratch lost to time. That’s equal to all of Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit three times over. We lost four to five bibles worth of Beethoven’s inner world. Sure, a lot of it would have been incomprehensible (in both content and handwriting.) Halves of conversations, grocery lists, and typical Beethoven-y nonsense. It’s been speculated that Schindler curated the remains so as to preserve an image of Beethoven as a reclusive, affected, tortured genius who lived for his art and only his art. And that is the image that’s held up in the popular narrative.

It’s not not true. He was known to be a grump. He was an alcoholic with a temper, hated small talk and politeness and he regarded himself as highbrow, overtly aware of his own genius. He was no social butterfly, but it was not from a lack of wanting; he felt his deafness and freakish disposition rendered most people inaccessible to him. He was a horrible gossip and a highly motivated shit-talker, deeply curious about the inner worlds of others, their idiot brothers-in-law and failing marriages. In his conversation books, he often wrote about his students, their progress, and contemplated his own skills as a teacher.

I don’t know why one shouldn’t eat dinner with his pupils, when at the table one finds so much opportunity to clarify many things, to take them to heart, that it would be a sin [Blatt 14r] not to take advantage of this opportunity. And how then is one to urge the pupils to contentedness, if they know that their teacher eats better mouthfuls than they do. // One lies more in the bosom of Nature; [Blatt 14v] people here are occupied with their stomach and their vanity more than they know. // One must be able to sacrifice everything in order to save himself; otherwise, he is lost.

The very end of Herz (notebook) 28 depicts a conversation between Beethoven and a travelling salesman who approaches him at a coffeehouse, a Sandra. (nickname for Alexander.) Their introduction is straightforward and chronological, and has a stable back and forth rhythm. Tt reads like a script. Then, certain lines are dropped, and topics switch rather abruptly, until the very last page of the notebook. It is presumed that the conversation doesn’t end there. Pages and pages beforehand, there are random “snippets of the Beethoven/Sandra conversation” scattered throughout. They were scrambling for more room to keep the conversation afloat.

The exchange also takes up considerably more space than eethoven’s conversations with his other friends and family. In part because Beethoven’s other conversations were between himself and his hearing friends and family. But there may also be something particularly deaf going on, in that Sandra, having a similar lived experience and feeling a clear kinship with Beethoven (the very first topic of conversation is the state of hearing technology, both parties sharing their experience and advice,) might’ve understood the importance of sparkling communication more intimitely than a hearing friend or family might’ve.

SANDRA: You must not laugh at me, if I tell you that it wasn’t until a week ago that I placed my only hope on a very old medical book. // That consists of nothing other than using the young top branches of the fir tree. // I shall write everything for you. BEETHOVEN: [Will you try] Galvanization? [//] I could [have done it] earlier, but [could] not stand [it]. [Blatt 43v] SANDRA: Please be so kind as to write for me the address where you live; I shall send you the complete prescription; it is very probable, because the treatment is completely natural. [//] [Blatt 44r] Perhaps both of us will be fortunate in restoring our ears to health this way. [//] BEETHOVEN: May I ask your name? [//] SANDRA: Sandra—[//] Your fellow countryman.117

I mean, they’re promising each other complete lists of their medical history and advice before they even get on a first-name basis. Beethoven was a huge grump, and that doesn’t disappear in his conversation with Sandra — he talks shit about his brother in law, calls him unintelligent, says the french have “destroyed him.” Sandra The Stranger jumps onto his French hate train. The passage lends itself to the idea that the two are on some level trying to impress one another, or at least validate a clearly shared bond. Beethoven learns that Sandra is a traveller, he begins to switch the language he is writing in —from German to French to Italian, sometimes in the middle of his sentences. He mentions his desire to travel, and Sandra uses it as an opportunity to compliment his clear intellect.

My brother’s marriage already proved both his lack of morality and his lack of intellect. [//] [Blatt 36v] I have been continuously sickly for 3 years, otherwise I would already be in London. // SANDRA: They value great genius there. // There would be a jubilee if you were to come and just presented your Schlacht bei Vittoria [Wellington’s Victory].121 // I heard it performed the first time. [Blatt 37r]

This exchange within the conversation books informs the way Beethoven interacted with his condition. He was a loner due to his artistic obsessions and his deep-seated shame.

But when he catches a glimpse of mutual understanding from a stranger in a coffeehouse, he seizes it. The dam breaks. He suddenly becomes a sparkling conversationalist, his language-per-sentence rate increases threefold. He’s a different Beethoven, weirdly vulnerable Beethoven. This man was clearly aching for community.

Beethoven’s disability caused him to develop workarounds in his music as well as his social life. He began to struggle hearing higher frequencies in particular, and the range of pitch in his work became deeper and tighter as a result. His favorite piano switched from an Italian model, one with a crisper and overall more sophisticated tone, to an English one made out of metal. The sound was wonkier, but the vibrations were more animated and booming, to better allow the sound to travel up his wrist, for him to feel the music.

[Exchange between Ludwig Von Beethoven and a music shop owner, a man referred to as Stein.]

Haven’t you tried playing on an upright piano? I am of the opinion that you could have nothing better.193 [//]<If I … [verb] … you> // We want to put it in front and place two horns in it, which will be directed toward your ears. // <It won’t do well if made of brass.> // <It is possible, but> Since it costs too much, and won’t stand [upright] well, we want to try it made of wood first. [//] [Blatt 84v] This paper attests that we did not use any tin. // But I believe that your ears would comprehend more with tin. // Indeed, that was also the case with Maelzel’s machine.194 //

Deaf as he was, Beethoven performed live through his mid-forties, which was well beyond the expectation for a composer. He never made any sort of public comment in defense of the deaf — there was no heroic instance in which he stood before the audience after bringing the house down with Symphony no. 5 and even acknowledged that he was experiencing it at all. In fact, he deliberately kept his declining condition away from the public for fear he would lose his status and therefore his ability to create.

Beethoven was deeply obsessive, and he wrote everything down. You can literally watch the progression of his thoughts forming. He repeats the same phrase over and over, backwards, in a different key, with a different harmony, or exactly the same for pages and pages, with his grumpy notes in the margins. No, not that one. It is better in C.

One imagines him pacing madly, bushy eyebrows knit together so intensely as if to function as an awning for the rest of his face.

He gave his personal notes the same neurotic treatment as his masterpieces. Even when he disappeared from public life altogether, he was obsessed with how others perceived him. Rather, him and his music — there was no separation between the two. In his famous letter to his brothers, he gives a deeply vulnerable and uncharacteristically concise account of his own cold behavior, his frustration with his hearing, and his need to keep composing as his sole defense against thoughts of suicide.

It was only my art that held me back. Oh, it seemed impossible to me to leave this world before I had produced all that I felt capable of producing, and so I prolonged this wretched existence

We seem to enjoy flattening Beethoven into this anti-social bobblehead figure of untouchable musical genius. Beethoven in popular myth is so genius, so in his own league; he ran circles around Vienna’s other composers while reckoning with the ultimate tragedy of his deafness on the side, which exacerbates his image as a divine being. Beethoven and his hearing loss get name-dropped for inspiration porn among people of the internet. Gary Oldman’s Beethoven in Immortal Belovedis very much a disconnected loner-genius trope, haunted by the oppressive weight of his intellect. Peanuts’ Shroeder literally worships Beethoven on his musical altar. The narrative loves a protagonist who is so much better than you, it makes him depressed, predestined for a life of solitude. The deeply frustrating bit is that this depiction is not entirely inaccurate, just incomplete.

But his framework, as it appears in the conversation books, is dominated by that tension — between his urge to retreat into his musical bubble, safe from the unmooring and frustration that comes from dealing with others — Shudder shudder — and his soul-crushingly pedestrian struggle with loneliness. It’s all there between his medical anxiety (relatable,) his dedication to creating systems of understanding others, and his constant ruminating on every nuance of every experience. Whether he’s getting weirdly personal with a stranger, pondering his teaching methods, or gossiping in a coffee house with Czerny, Beethoven was dealing with the same questions as most humans. Learning how to function as a social animal, while getting what one wants out of life.

The conversation books, the Heiligenstadt Testament, everything that survived of the frantic cave paintings Beethoven scrawled over the final decade of his life, they offer a glimpse into the guy’s superhuman impenetrable sparkly geode of a brain. And he’s just, like, a guy. Who happens to be socially awkward, deeply passionate about his art, and comes with some serious personal baggage. He’s insecure, neurotic, and closed-off, until he meets a like-minded stranger in a coffeehouse, and sparks fly.

To be sure, Beethoven was in a league of his own. But his struggles weren’t because he was some untouchable unicorn, it was because he was a person. Beethoven isn’t tragic because he wasn’t like anyone else. He’s tragic because his problems are the problems of so many others. He’s tragic not because he’s a genius, but because a genius like him spent his whole life believing he was an island, and it didn’t have to be that way.