Having without Hoarding

Recently we welcomed some friends for a visit. They are globally minded folks whose life paths have crossed ours in a couple of different places on this earth. They are polyglots - speaking multiple languages between them - and they operate with a grounded, generous, and responsible cosmopolitanism which is refreshing. They have immense courtesy and cultural understanding, recognizable as a deep humility, and a keen sense of humor that doesn’t shy away from tough questions. They love exploring and taking long treks, and they relished showing us just how far they ventured each day on a mapping application.

On their first day here, we took a walk with them through the older part of Copenhagen with its storied sights, statues, and squares. My husband and I pointed out some interesting buildings, threading contemporary and historical tidbits into the built landscape we were walking through. It was all so satisfying, walking in the fresh evening air, the buildings growing ever more resplendent as the sun aged to a rosy-orange hue.

One friend sighed and, turning to his spouse, said, “You know, even if we were millionaires, what would we be doing? We’d be doing exactly this. I love doing this.”

The sigh, the active pause, and the rhetorical practice they had cultivated as a couple with that simple phrase engaged something in all of us. He was actively exercising the muscle of contentment. It was like he opened a window that allowed even fresher air to flow into an already fresh evening.

That was grace. I’ll admit, at first, the splash of grace confused me. My mind scrambled to figure out what he meant. Was he was imagining being a king in the nearby castle or on a statue on the plinth in center of the square? Or was he wishing that they were millionaires, living in Copenhagen?

No. All he said and all he meant was, “I’d be doing this very thing no matter how much money I had in the bank.” He was bringing to mind — his and ours — the present moment, the actual happening, attending to and savoring the richness of life right then and there.

Having more, especially more money, would not have changed a single thing about that actual moment for any of us. The abundance was all right then and there. His pausing sigh and comment invited us all to enter more deeply into moment and its mysteries, but there was nothing about it that allowed us to hold onto it forever. But we could still have and hold it for a moment — pausing, attending, practicing contentment, and actively enjoying it, receiving what we were being given.

The manna of this particular moment of practiced eternality returned to me as we walked through the Kon-Tiki Museum last weekend in Oslo. The museum celebrates the life and adventures of Norwegian ethnographer and explorer Thor Heyerdahl, centered around his experience with a small crew of friends on the Kon-Tiki raft. They built that raft to try to prove a theory, using ancient construction methods, and then crossed the Pacific Ocean in 101 days in 1947 on it, driven west by strong currents and trade winds. The adventure proved that the so-called “primitive” methods of raft-building made possible what the modern experts declared impossible. The experience was full of great risk and no guarantees, but the crew still spoke of their time on the raft with great pleasure.

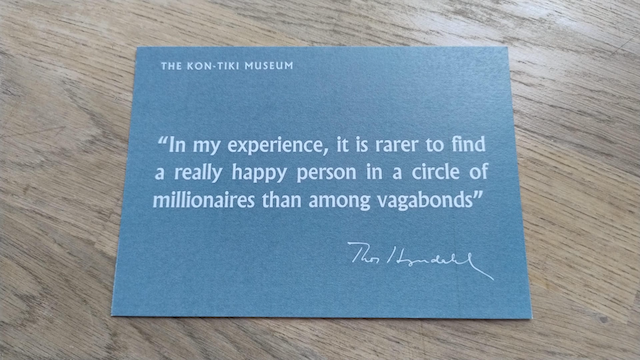

Heyerdahl’s many interesting adventures garnered him fame that lent him authority in public opinion. It’s a mercy that this dynamic didn’t seem to dement or deceive him quite as horrifically as it usually does to human beings. He was clearly a man who kept reaching and searching for truth in the world, as responsibly as he knew how, imperfectly but with a kind of adventurous humility. He became a prolific writer in the midst of his many adventures, and he peppered his books with nuggets of wisdom. Some of these phrases were printed on postcards in the museum gift shop, one of them drawing me right back to that moment of practiced contentment with our friends:

The point isn’t “poor people are happier than the rich.” That’s obviously not true, and a tired sentimentality traded by many of us to avoid our God-commanded responsibilities to give to the poor. (Jesus not only embraces this command and distills it even further: what you do for them, you do for me. What you don’t do for them, you don’t do for me.) Poverty is miserable, period, and expensive at that.

But when one periodically glimpses the kind of poverty unique to the wealthy, it can be shocking to discover how discontented they are, how wealth can impoverish rather than enrich. (Indeed, trying to satisfy that discontentment can lead the wealthy into funding a great deal of mischief and real destruction, spreading their impoverishment around.) It is a grace to remember, and practice, that the riches that carry great meaning, purpose, and satisfaction are available to all of us, no matter our station, but it often takes practice, actual effort, to bring it to mind and dwell on it. Rich, middle, or poor, we all move in this world as vagabonds — wandering, driven, and searching — and tempted to take and hoard what is available to have, hold, and savor freely.

It’s enough to make a person sigh. But in the space of a sigh, we might catch the scent of fresher air, and remember to begin again.