Why we should be designing for intermittency

Australian study shows how electric hot water heaters can shave peak loads and deal with intermittency.

Recent research from Australia found that using electric water heaters to store renewable energy could do the work of 2 million home batteries and save billions. The study authors note that about a fifth of Australian residential greenhouse gas emissions come from domestic hot water, which could be made with renewable off-peak energy and stored in a decently insulated tank.

It’s a clever way of dealing with the lack of solar power at night, and is the most common and obvious form of what could be called “design for intermittency.”

Kris De Decker of Low Tech Magazine noted in a 2017 article that before the Industrial Revolution, the world used to accept intermittency as a matter of course.

"Because of their limited technological options for dealing with the variability of renewable energy sources, our ancestors mainly resorted to a strategy that we have largely forgotten about: they adapted their energy demand to the variable energy supply. In other words, they accepted that renewable energy was not always available and acted accordingly. For example, windmills and sailboats were simply not operated when there was no wind."

They learned how to build mill ponds to store water, and how the trade winds work to make sailing relatively reliable. De Decker suggests that we should take the same approach.

"As a strategy to deal with variable energy sources, adjusting energy demand to renewable energy supply is just as valuable a solution today as it was in pre-industrial times. However, this does not mean that we need to go back to pre-industrial means. We have better technology available, which makes it much easier to synchronize the economic demands with the vagaries of the weather."

But nobody talks much about dealing with the demand side, and worry instead about the supply side, with 1.8 billion new electric cars and fleets of new power plants to feed them and our all-electric homes. Engineer Nick Grant complained about this in BDOnline years ago:

“My hunch is that the world is divided into “less is more” demand side people, who focus on reducing their demand for emissions-heavy products and processes, and “less is a bore” supply side people, who look for solutions within the sector that emits them – it is a personality trait. Inspired by a typo, Amory Lovins coined the term negawatts (and negalitres) to quantify energy or water that is saved rather than generated. This is a difficult idea. Not using resources is a surprisingly abstract concept that needs a catchy name. It is easy to measure what we generate or consume, but savings can’t be directly metered and can only be estimated based on assumptions about what the base case might have been.”

So we have supply-siders like Mark Perez, suggesting that we have to oversize the supply of renewables by a factor of three; Others, like Michael Liebreich suggest that we have to fill salt caverns with hydrogen to deal with seasonal intermittency. We get Simon Michaux estimating that we need an additional 37,670 terawatt-hours of electricity to run everything, which “translates into an extra 221,594 new power plants” Michaux also makes the case that we don’t have the materials and the resources to make this transformation to an all-electric world, thanks to our mineral blindness. This is why we have to think like the “less is more” demand-side people; the supply side looks impossibly daunting.

Looking at the demand side and Australian water heaters has caused me to rethink some earlier opinions. I have long been dismissive of smart technology, writing ten years ago when the Nest thermostat was introduced, In praise of the dumb home. Built to the Passivhaus standard, I noted that “A Nest thermostat probably wouldn't do much good there because with 18" of insulation, and careful placement of high quality windows, you barely need to heat or cool it at all. A smart thermostat is going to be bored stupid.” Instead of Powerwall batteries, I called for our homes and buildings to be thermal batteries. But the Australian research is instructive.

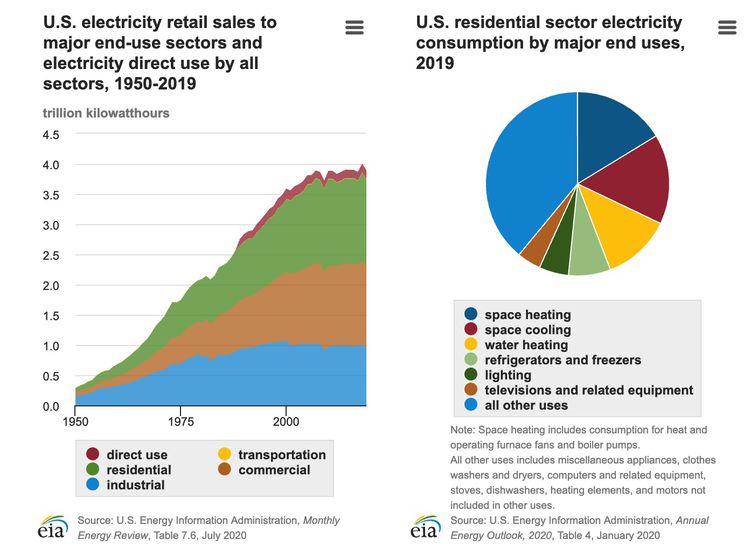

When I look at where our electricity is going in our homes, I am beginning to rethink my aversion to smart tech. So many of these end uses in our homes could be controlled to adjust for intermittency or to shave the peak load, and the peak is what matters most. Heating, cooling, and water heating are almost half our residential consumption, and many of the “other uses” like clothes dryers and fridges could be turned off at peak times.

Even our idiot provincial government in Ontario gets this; after cancelling over 700 renewable energy projects they find they don’t have enough electricity, so it will pay people to let the utility control their air conditioning when the grid is stressed. According to the Star:

The Peak Perks energy conservation program, announced Thursday, will take advantage of the estimated 600,000 smart thermostats installed in homes across the province to automatically turn down participants’ air conditioning a few degrees when the electrical grid is straining under peak demand.

Because the grid is built to meet demand for those few peak hours per year, reducing that peak means less new generation will need to be built, said Energy Minister Todd Smith.

“The cheapest generation is the one you don’t have to build,” he said.

Put this kind of technology in homes that are built like thermal batteries and you have significantly reduced demand, which is a lot easier than increasing supply. Combine all this with a better grid that can move electricity around from where the sun is shining, the winds are blowing and the water is flowing, and intermittency doesn’t look like such a big problem.

All the engineers say we need hydrogen and nuclear and a massive increase in clean electricity supply. I am not so sure, but then what do I know, I’m just an architect. I remain convinced that the answer is to reduce demand through Passivhaus level standards of efficiency, more multifamily housing with fewer exterior walls, built in walkable communities with fewer cars and more bikes.

Or as we noted earlier, Less is Less.