Thoughts from a catacomb

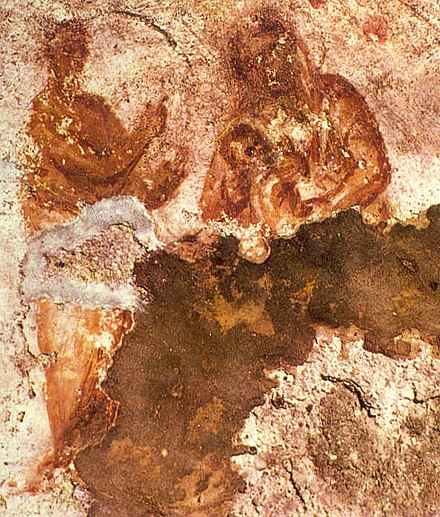

On our first day in Rome, we saw the oldest known image of the Virgin Mary. Here she is on the right:

She’s in the Catacombs of Priscilla, one of the many underground cemeteries that were once outside Rome’s city walls and are now in its neighborhoods beyond the center. The Catacombs of Priscilla were near our hotel, and it seemed like a convenient thing to do on our first morning, when we were sure to be jet lagged and perhaps not up to facing the metro quite yet. We were two of four people on our tour.

The oldest part of the Catacombs of Priscilla date to the third century AD, during the Roman Empire. Priscilla was a Christian noblewoman who donated part of her estate to build the catacombs, which extend through 13 kilometers of labyrinthine underground tunnels. The walls are covered in small niches where bodies were once placed, sealed behind a layer of terracotta or marble. Apparently the bodies once included those of seven popes and hundreds of martyrs, some of which were taken, centuries after their burial, for the emerging relic trade.

In some of the larger tombs for noble families, early Christian art and iconography can still be seen. Most of the images refer to Old Testament stories, many of them have roots in polytheistic Roman symbols, and none of them look like the sacred art I’m familiar with. For example, there are no crucifixes or crosses until several centuries later—according to our guide, Christians of Priscilla’s time were not enthused about using a cross as a symbol when they were still sometimes being crucified themselves. There are, somewhat more recognizably, palms and fish, shepherds and feasts, and whales that look like dragons. On the gravestone of a shoemaker, there is an image of a sandal. And there is Mary, holding her baby, for something close to the first time.

The person who painted the Virgin Mary on the ceiling of this catacomb was probably not actually the first to have the idea of representing her. (Archaeology never finds the true first of anything.) But it was still staggering to see her there and realize, in a way I never had before, that there had been a first time. That this symbol I’m so familiar with came from somewhere. That at some point, she was new.

What’s always drawn me to writing about archaeology is the mystery. I’ve often said it feels like writing speculative fiction, trying to imagine myself into a time and culture distant from my own but that was once just as vivid, complicated, and alive. I write about archaeology because I want to glimpse ways of being human I never could have imagined or extrapolated from my experience of the world and the societies I know. I want to know how vast history is and feel, as viscerally as possible, how little of it has anything to do with me.

I felt that sense of deep time and unknowability in the catacombs, the lighting bolt of realizing, yet again, that the way I expect the world to be was not the way it has always been. But there, the mystery that grabbed me wasn’t the past, or how the people who lived in it saw their world. It was how someone’s new idea became an old one, how impossible it was for me to see this Virgin Mary without also seeing all of her daughters, and how the shape of the present is always, invisibly but inescapably, determined by the topography of the past. The mystery was us.