Bologna’s cabinets of curiosities

Featuring a dissection gone wrong

Editorial note: We are now home in Mexico City! Please excuse the lack of a newsletter last Sunday; we landed at 5 a.m. that morning after a 14 hour flight.

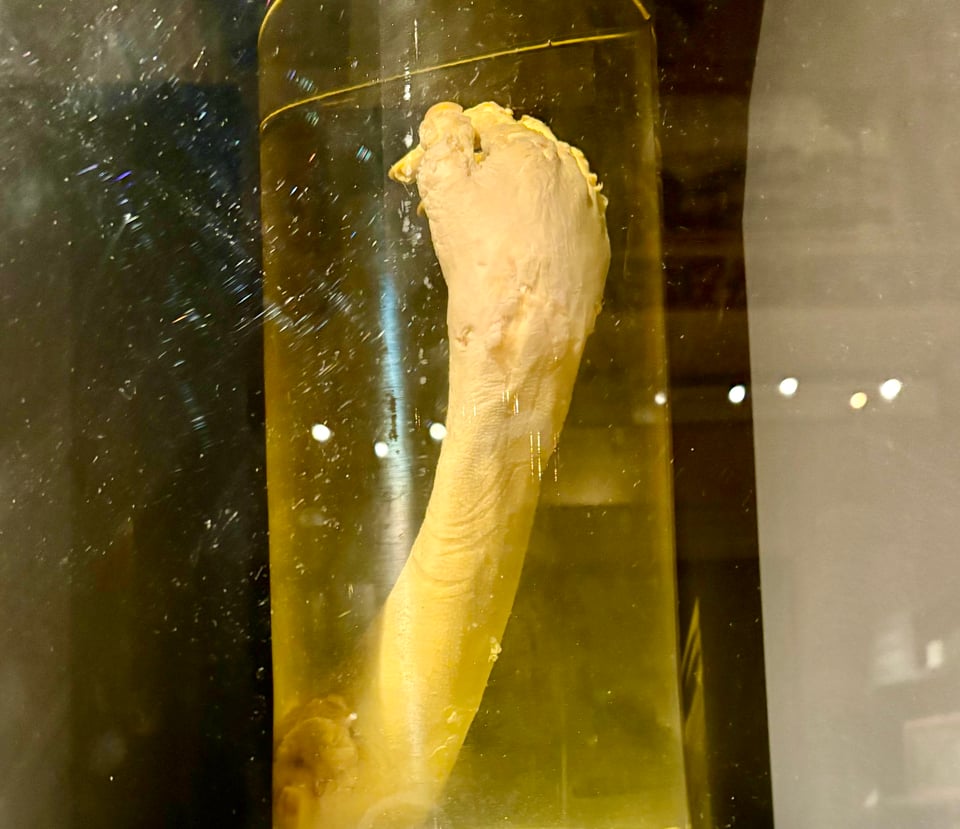

In the Museo di Palazzo Poggi in Bologna, a disembodied forearm floats in a jar. It belonged to Antonio Alessandrini, the first director of the Museum of Comparative Anatomy, in this city with the oldest continuously operating university in the world. “The arm had to be amputated following an accident during a dissection,” says the information label, dispassionately.

Possibly the ill-fated dissection occurred in Bologna’s Anatomical Theater, a spruce-lined room decorated with carved statues of twelve famous doctors and two skinned men, their exposed musculature presumably based on and informing the dissections that took place on a marble table in the center of the room. The skinned men hold aloft a platform upon which sits an allegory of Anatomy, looking very much like Mary, being offered a femur by an angel.

At the end of December, there was a huge line to visit the Anatomical Theater, but a few days later, Palazzo Poggi was almost empty. If people wanted to commune with the grisly, queasy beginnings of modern science and medicine, they’d chosen the wrong place. The skinned men were positively staid and elegant compared to Alessandrini’s forearm, with stringy pieces of flesh floating around its curved fingers. Not to mention the detailed wax models of both healthy and diseased body parts, including seemingly everything that could go wrong with a fetus and/or uterus during pregnancy. (I didn’t take pictures.) The Museo di Palazzo Poggi does not mess around. Nor did the sixteenth to nineteenth century scientists who first assembled the collections and made the models it displays.

The museum, like others in Bologna, grows out of a cabinet of curiosity, the Renaissance collections that were the precursors of modern natural history museums. In particular, it draws from the curiosities collected by the sixteenth century naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi, and it displays at least some of the original objects—both natural and cultural—in the same jumbled, fantastical ways he once arranged and appreciated them. In that way, it’s a museum of the concept of museums, and not just their delightful side. A select few objects and specimens from the Americas powerfully represent the source, and the price, of the wonder Europeans got to feel when the world suddenly, unexpectedly, and irrevocably expanded into the one we know today.

The modern museum—and the science it nurtured—grows out of the tension between lavishing the most intense, loving interest on pieces of nature and culture, while also insisting that the best way to appreciate them is to rip them away from their original context, including the people who would understand them differently. Most museums try to let you forget that, but not the Museo di Palazzo Poggi. Knowing, and organizing, the world in this way requires a certain amount of violence, and even the people inflicting it aren’t spared the long tail of its consequences. Just ask Antonio Alessandrini.

Further reading

For more about cabinets of curiosities and the history of museums, I recommend the utterly enchanting (and short!) Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder by Lawrence Weschler, about my beloved Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles and so much more. For more on the price of Renaissance wonder, Marvelous Possessions by Stephen Greenblatt is the classic.