LBP - Issue № 11 - Germany & Admitting Mistakes

Part two of my research trip to Germany which involves interviews, a donkey, and a confession!

LBP - Issue № 11 - Germany & Admitting Mistakes

This is the second part of my report from Germany at the end of August. Originally, the Ottmar Mergenthaler Museum was going to be a part of this issue, but it quickly got out of hand in the best way possible and became LBP Newsletter № 10 and a blog post on my personal site.

So here is part two; I hope you enjoy!

Digging Deep in Berlin

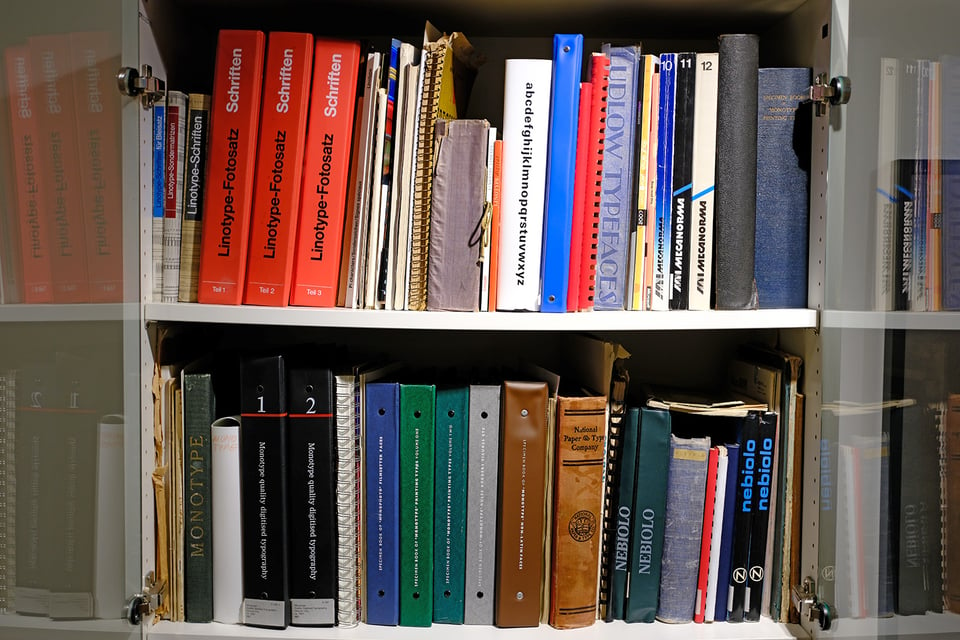

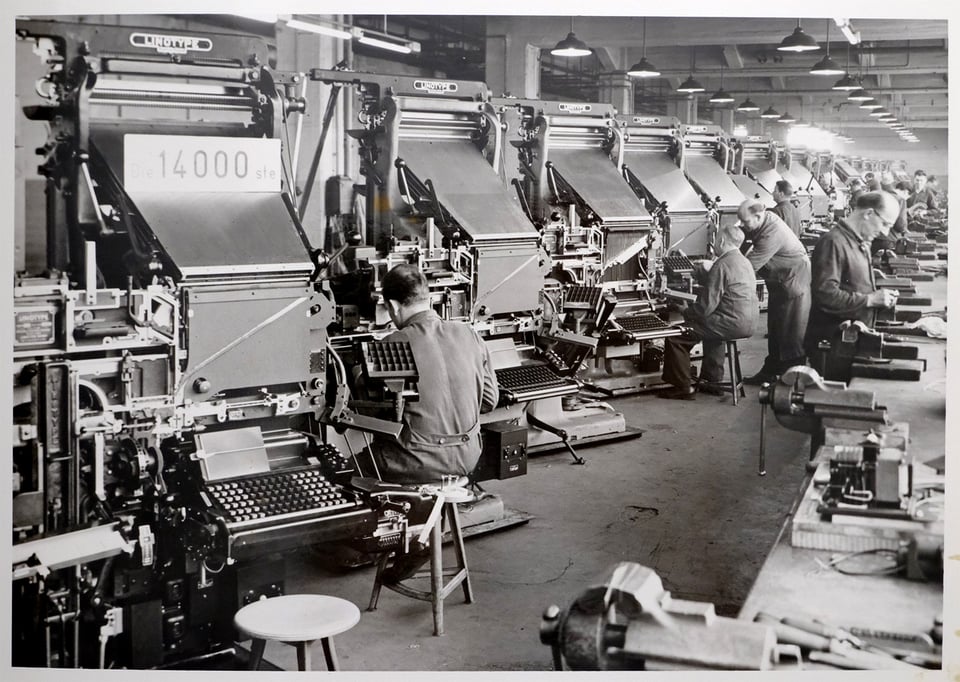

I spent two days at the Berlin office of Monotype (where the collections of Monotype, Linotype GmbH, and URW have been amassed). With so many beautiful old books and ephemera, I had to keep myself laser-focused on Linotype-related items — not allowing myself to stray into the rare and beautiful specimens from the dozens of defunct European type foundries. IT WAS DIFFICULT, my friends, but I stayed on the straight-and-narrow.

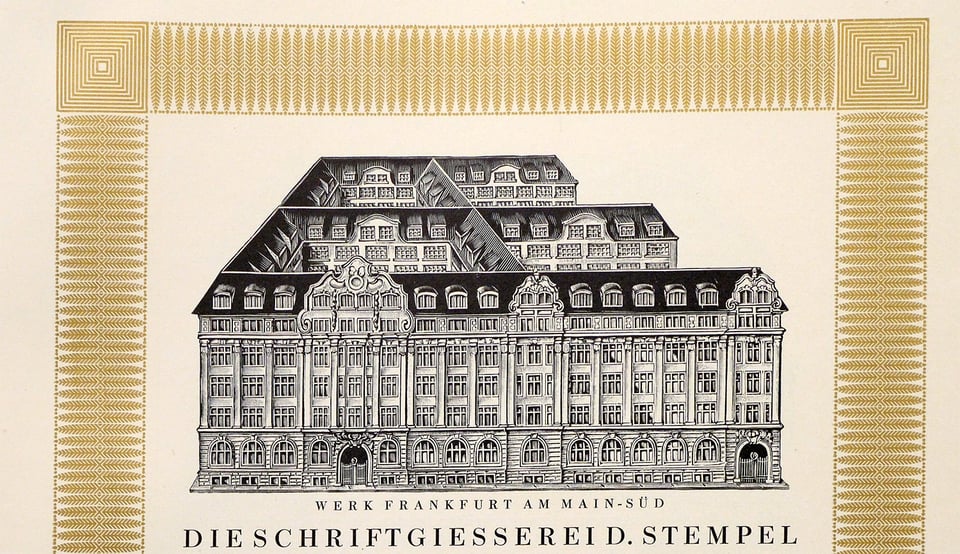

My goal was to understand the various German Linotype companies. One of the many things I learned was that the relationship between Linotype and the D. Stempel AG type foundry was exceptionally close from nearly the beginning of the German company. Stempel was a type foundry that manufactured hand-set metal type, but in 1900 signed a contract to be the designers of type and manufactures of matrices for the Linotype machine. This is different than the US or UK Linotype companies and explains some findings that had confused me earlier in my research.

Over the years, Linotype ended up purchasing more and more of a stake in D. Stempel AG and eventually fully controlled it after WWII. Doing business this way allowed Linotype access to the best designers and the best precision manufacturing in Germany, so it was considered a win-win for both companies. Additionally, Linotype had access to the design catalog of the many smaller German type foundries that Stempel had acquired over the years and Stempel cast hand-set versions of many Linotype designs.

It’s still not clear how much each Linotype company (American, German, and British) influenced the decision of other branches of the company, but they often collaborated. But: there is the detail of World War I and World War II, which obviously divided nations and the Linotype company for many years. How did these relations work before, during, and after the wars? I’m in the middle of researching into this question currently.

Interviewing Henning

Firsthand interviews are exceptionally important to my book. Learning from people’s experience and hearing personal connections is what will color and fill in the details. I interviewed Henning Krause — a current Monotype colleague and someone whose love of typography and collection of old typography books might even exceed my own! 😳

Henning has worked in various roles at Monotype for the past 11 years and before that, he was a type designer for 17 years. Starting out, he ran his own type design studio and then became a Font Production Manager at Linotype, slowly moving more into marketing and project management when it was acquired by Monotype in 2013.

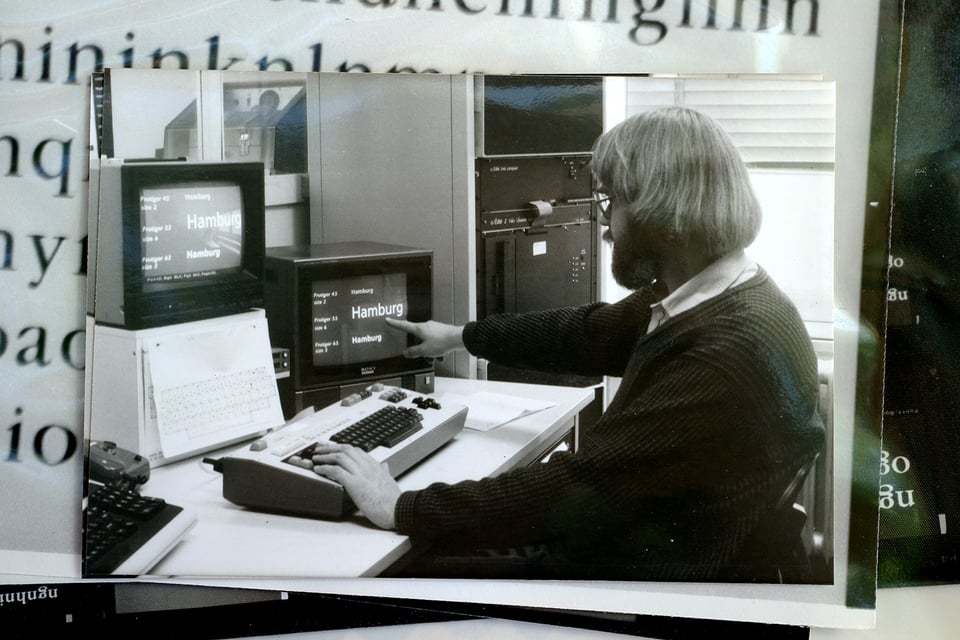

Henning gave me invaluable insight into the connection between industrialization and new technologies and how they have continually reinvented the typographic landscape and the tools that journalists, designers, and printers have used. From Gutenberg to hot-metal to photo to digital type (and dare I mention AI?), each revolution has caused massive upheaval and change in the way that society communicates and he helped tie together these threads.

Henning’s encyclopedic knowledge of type and printing history in Europe is just that — encyclopedic and extremely helpful to this project.

Just Me, Otmar, and a Few Donkeys

As you read in the last newsletter, I spent two days with Otmar Hoefer — one day at the Ottmar Mergenthaler museum and a second day at his home in rural Rhein-Lahn-Kreis, Germany. Along with being an expert in type and the Linotype, Otmar and his late wife Barbara raised a special type of French donkey on their farm, helping preserve them from near extinction. It was a beautiful, warm September day, so we sat outside for the interview while a donkey named Gustave was several feet away, completely uninterested in what we were discussing.

I chose to interview Otmar because he is one of those “missing link” people who has knowledge about the Linotype company for many decades. He started his career in 1969 at a layout typesetting company where they had two Linotypes along with early phototypesetting machines. He eventually got a job working for D. Stempel AG educating people on how to use Stempel photoheadliner machines while traveling all around Germany. I think this explains why he has a love for long road trips like the two that we have now made together!

Otmar was involved with marketing for Linotype for many years and was the project manager on the Neue Helvetica project and worked with Adrian Frutiger on the Avenir release. He had so many great stories about adapting to new technologies and machines. Throughout the interview, it was obvious that he looked back on his career at Linotype — and especially the people — with fondness. He also helped me understand how Linotype eventually was sold by Heidelberger and merged with Monotype.

To get this personal and inside view of how the German company worked made the entire trip valuable and worthwhile. I’m thankful for Otmar’s hospitality and the opportunity to spend a day with him and Gustave.

Mea Culpa

I have a confession to make to you, dear readers. When I launched this project in 2023, the website and launch video specifically asked the question, “Why didn’t Linotype survive the transition to photo and computer technology?” With 1.5 years of research under my belt, I come to you to say: I WAS COMPLETELY WRONG.

Linotype not only “made the transition” to these technologies, but was the most dominant and largest player in photo and early digital technology. Linotype was first to market with a “true” phototypesetter with the Linofilm (instead of the goofy line-caster-with-photo-mats like the Intertype Fotosetter).

They sold thousands of various Linotron models and the Linotronic 300 laser machine was considered the top-of-the-line for years. Linotype was also integral in the fight to establish the technology behind digital fonts and had an exclusive agreement to work with Adobe’s new-at-the-time PostScript description language.

So, apologies to the few people who kindly, but strongly, reminded me how dumb and mislead I was. You know who you are ;-)

But that is what this whole project is about, isn’t it? I am free to change my opinion as I gather new information. Somehow after all these years, the Linotype machine, the company, and importantly the people continue to help me uncover hidden knowledge, new perspectives, and deeper ways how this machine/company/enterprise impacted the entire world. What a fun thing I get to be involved in.

I have updated the project website, removed the incorrect questions, and rearranged the site to make the project feel like it is in-progress, rather than just starting. I’m deep in this and you’re right there with me.

Closing Thoughts and Links

Just this week, I finished transcribing the interviews with Otmar and Henning that I described above. My final step is to re-read the transcripts, highlighting the most important stories that give me the best understanding of the German Linotype company. It’s a slow process, but one I enjoy and am confident will pay off in the long run.

Finally, here are three internet hyperlinks that you may find interesting:

- Video: “Drunken with Rum and Prosperity: the Introduction of the Linotype to Australia” my ATypI Brisbane talk from April 2024

- Video: My ATypI Brisbane Post-Film Q&A Session

- Photos: Flickr collections from my research social media posts

As this email is going out in mid-November, this is the final newsletter of 2024. I’ve been able to tell some great stories this year and there is not a week that goes by where I’m not immensely thankful for your interest and support.

Wishing for peace this season,

Doug Wilson