Maybe it's time to do the work again

In this newsletter: Figuring out how to be creative again.

First time seeing this newsletter?

So here’s the honest truth, which I think I’ve hinted at but haven’t come right out and said: I am not succeeding at writing right now.

I have a book underway, one with a (let’s say) flexible deadline, but one I feel pressure every day to deliver. I’m so close—a few weeks’ worth of work, perhaps?—to putting a bow on the current draft. But I can’t do it. I never was good at tying bows, to be honest.

I’m succeeding at my everyday work. Each morning I wake early, I scribble a bit in my journal, and then I head downstairs, to my office—study, got to remember to call it a study—where I spend the day designing software. I’ve been a designer for twenty-two years now. It’s hard work, and I’m still learning new things all the time. I’ve been writing novels for longer than that—just barely—and that’s also hard work, and I’ve learned maybe eight percent of the total amount of things I could learn about being a writer. The difference? Software design produces daily physical artifacts: Proof that I'm doing something valuable. Proof that I'm getting better, that the thing I'm making is being improved with every pixel I shove around.

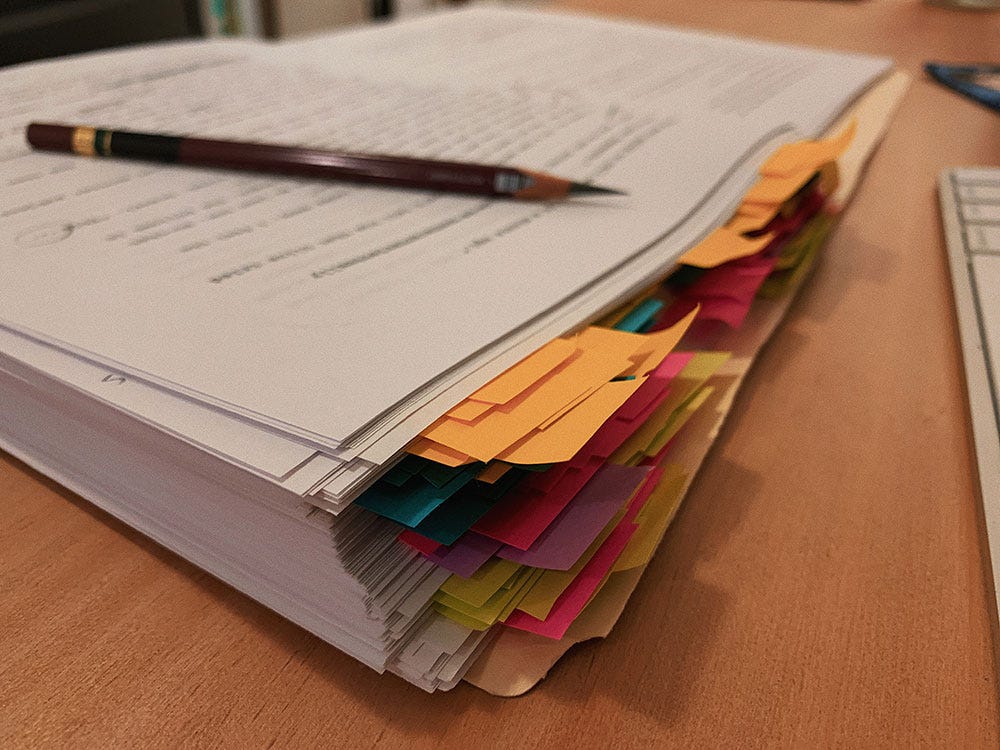

Writing's a little harder. Yes, you produce pages. But those pages feel soft and unreal until you reach some sort of milestone. Maybe that milestone is a completed draft that you’ve printed out, the pages hot, the study filled with that awful toner smell; maybe it's a published novel, spine-out on the shelf.

The thing is, for reasons of global crisis and personal implosions related to global crisis, I'm not working the way I wish I was.

I confessed this to Felicia recently, and though she's been doing her own version of software design—knitting sweater after sweater, sewing masks for our family and friends—she's also booting official projects down the line a bit. We've made a deal: We're going to attempt to work on our stalled projects together, in small bubbles of time, in an effort to jump the engine. Late last week, we took our first swing at this: A half-hour, we decided, a safe crevice in which to do a small amount of work. A half-hour later, she’d produced nine rows of her project, and I’d worked through five pages of revisions. “Don’t despise small beginnings,” she reminded me, when we finished.

The next evening we did it again, and Squish joined us, reading her book while Radar, our chihuahua, snuggled into his bed nearby. I pushed through a dozen more pages.

My social media, the daily newsletters I receive, even the weekly newsletters I write, are filled with reassurance that the rest of the world isn't creating right now, either, and that it's totally okay to ease up and take a break from Being Mr. Productive. I get it. I want to wallow in that for a year.

But yesterday I stumbled across this New York Times profile about Jerry Seinfeld and how he's coping with quarantine and pandemic:

While he has been sheltering in place with his wife, Jessica, and their three children, he is as devoted as ever to his daily rituals and habits, and still inescapably prone to atomic-level observations of human behavior.

Emphasis mine.

If you've ever listened to Jerry Seinfeld talk about writing, you know that he's fanatically committed to routine and keeping his work in perspective.

Austin Kleon wrote about both of these things:

The comedian Jerry Seinfeld has a wall calendar method that helps him stick to his daily joke writing. You start by breaking your work into daily chunks. Each day, when you’re finished with your work, make a big fat X in the day’s box. Every day, instead of worrying about your total progress, your goal is to just fill a box.

“After a few days you’ll have a chain,” Seinfeld says. “Just keep at it and the chain will grow longer every day. You’ll like seeing that chain, especially when you get a few weeks under your belt. Your only job next is to not break the chain.”

and

Jerry Seinfeld kept photos from the Hubble Space Telescope up on the wall in the Seinfeld writing room. “It would calm me when I would start to think that what I was doing was important,” he told Judd Apatow, in _Sick in the Head_. “You look at some pictures from the Hubble Telescope and you snap out of it.” When Apatow said that sounded depressing, Seinfeld replied, “People always say it makes them feel insignificant, but I don’t find being insignificant depressing. I find it uplifting.”

So I'm reading the Times piece, and find this:

I still have a writing session every day. It’s another thing that organizes your mind. The coffee goes here. The pad goes here. The notes go here. My writing technique is just: You can’t do anything else. You don’t have to write, but you can’t do anything else. The writing is such an ordeal. That sustains me.

And then, because the internet is a series of interconnected things, and I follow a lot of blogs, I bumped into this post by Rick LePage, via Daring Fireball:

One recent night, during a bout of insomnia, I was hit with a stark thought. Actually, it was really more of a command:

“Get your mind working again.”

I thought about this for an hour or so, mulling the contours of the phrase. I know what “get your mind working” literally means, but the path wasn’t evident to me. I have things to do, projects that I’m working on, and I’m struggling to get them done. It’s all the other crap that’s getting in the way, making those things more difficult to accomplish.

And then—here's the little magical link—Rick wrote:

A day later, in a little bit of serendipity, I read an interview with Jerry Seinfeld in the New York Times. It was an interesting read, but I was struck immediately by what he said when asked about how he’s working through isolation:

“I still have a writing session every day. It’s another thing that organizes your mind. The coffee goes here. The pad goes here. The notes go here. My writing technique is just: You can’t do anything else. You don’t have to write, but you can’t do anything else. The writing is such an ordeal. That sustains me.”

What Seinfeld articulated so crisply is what my brain was saying to me the other night: get out there and work on your craft.

It is hard, and it should be hard. It can’t be any other way. Work to overcome the noise as best you can, by doing the things you need to be doing. Not those projects necessarily, but that which you feel you are here to do.

That last bit really landed for me. Writing is hard…right now. Whatever project you’re working on is hard right now. But don’t forget that writing, or your projects, were hard before, too. They’re always hard. It isn’t the work that’s changed. It’s the world. It’s us.

Look, here's the thing: It's still okay to not be productive. You take care of yourself in the way you need to be cared for right now. There’s speculation we might still be home for some time yet. So: If you find yourself lifting your head at some point, thinking, I used to do a thing, then go with that. See if you can do that thing again.

For the last several days, I’ve done a little revision work each day. I’m moving forward, mostly slowly. The book is hard work, and I can already see the next project looming. I’d like that one to be a little less hard. I’ve signed myself up for a writing workshop that starts next month; maybe it’ll shake a few things loose.

It's time for me to try to create again. I’ll let you know how it goes. Maybe you can tell me how you’re doing, too.

✏️Stay safe (and stay home)!

Jg

Morning at Hill House. Pretty as it is, it won’t make me do the work. That’s my job.

About the author

Jason Gurley is the author of Awake in the World, Eleanor, and other books. He lives and writes on a hill in Scappoose, Oregon. More at www.jasongurley.com or on Instagram.

If you enjoy this newsletter

Please share it with a friend! This newsletter is free, but it takes time to create and curate. If you've enjoyed it, consider supporting this author by buying a book.

If this is the first time you’ve seen this newsletter, you can subscribe here.

Copyright © 2020 Jason Gurley. All rights reserved.

This newsletter may contain affiliate links.