The Price of Salt by Patricia Highmith (1952)

Dear reader,

In any piece that invokes The Price of Salt, it will inevitably be mentioned that that it's the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. Writing in 1989, Patricia Highsmith remarked that

“prior to this book, homosexuals male and female in American novels had had to pay for their deviation by cutting their wrists, drowning themselves in a pool, or by switching to heterosexuality (so it was stated), or by collapsing—alone and miserable and shunned—in a depression equal to hell.” (292) It makes sense then that the novel was an instant lesbian classic, a paperback bestseller that remained in print throughout the 20th century, and the consistent subject of letters to Highsmith until her death in 2005.

The happy ending in question: having fallen in love, consummated their relationship, and learned to see one another as full people, Therese and Carol are able to have a future together, but only because Carol has given up custody of her daughter, who she desperately loves, in her divorce. A hopeful ending by the standards of 1952, when a same-sex relationship would have been seen as completely incompatible with a “normal” family life, less so today when same-sex couples can marry, adopt, or bring a U-haul on the second date without most Americans batting an eye.

So why, nearly ten years post-Obergefell, does this novel still resonate? Put differently, in a context where the central tension of this novel no longer exists, or else exists in a drastically different form, why does it still work, at least for this reader?

Before I get into that, here's the plot for anyone who's unfamiliar: 19 year-old set designer Therese is working a holiday shift at a department store when she meets 30 year-old Carol, a cooly elegant Hitchcock blonde looking for a doll for her daughter. They meet up for a series of lunches in Manhattan and charged but chaste nights at Carol's New Jersey home before going on a roadtrip out West. While traveling, they confess their love for one another and finally have sex, only to learn that they've been followed by a detective sent by Carol's husband Harge, who's looking for evidence to use against her in their divorce proceedings. They run from the detective only to learn that recorded evidence of their affair has already been sent back to New York. They return to the East, Carol capitulates to Harge, and the novel ends with Therese thinking,

“it was Carol she loved and would always love. Oh, in a different way now because she was a different person, and it was like meeting Carol all over again, but it was still Carol and no one else. It would be Carol, in a thousand cities, a thousand houses, in foreign lands where they would go together, in heaven and in hell.” (287)

I've struggled to sum up why I, at least, enjoy this novel because there is simply so much in it. There are the pleasures of a thriller: the mounting tension that breaks only to mount again, the high speed chase, the menace of a loaded gun. There are the satisfactions of a romance: the frisson of the first meeting, the aching feeling of the pair not quite kissing yet, the promise of a love that goes on after the last page. But what I keep landing on is the structure of the Bildungsroman, and more specifically the Künstlerroman (sorry, I was a German major, I come by it honestly). In a Bildungsroman, a naive character who wants to live counter to bourgeois values goes out into the world, learns and experiences new things, cultivates oneself, and returns changed. In the most traditional examples, the character will reconcile themselves to the values of the society around them and renounce their childish desires. In a Künstlerroman, the character recommits themselves to living in opposition to the conventional world and pursues life as a mature artist.1

The Therese we meet at the beginning of The Price of Salt is ambitious, but aimless, floating through the world rather than coming into contact with it directly. She knows that she wants to design sets for great plays, but instead she spends her days selling dolls in glass cases and making uninspired models. She can't picture being married to her boyfriend, Richard, but constantly finds herself agreeing to spending time with him, only half paying attention when he, say, recommends that she reads The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Shy and unsure, she detaches from the world, even after she meets Carol. As Carol tells Therese,

“You so prefer things reflected in glass, don’t you? You have your private conception of everything. […] How do you ever expect to create anything if you get all your experiences secondhand?” (177-178).

To me, this is the question at the heart of the novel: can Therese move from the theoretical, “reflected in glass” world of her own head into the flesh and blood world of love, sexuality, and artistic creation? Only, Highsmith tells us, if she allows herself to get close to Carol and Carol opens herself up to Therese in return. Only if she engages with the world around her and allows herself to be changed by love. This requires learning to see Carol as more than the icy surface onto which Therese can project her desires for a more exciting life. By sharing her true self with Carol—not just her physical self, but also the emotional truth of her difficult childhood and her present dissatisfaction—and seeing Carol at her lowest moments, she's able to go beyond the image of her and to truly love her,

“the Carol who was not a picture, but a woman with a child and a husband, with freckles on her hands and a habit of cursing, of growing melancholy at unexpected moments, with a bad habit of indulging her will.” (269)

That, in my opinion, is just as relevant a question in 2024 as it was in 1952.

Do they dare speak its name?

The words “lesbian“ never appears in The Price of Salt, nor does “homosexual“ or older terms for queer people like “invert.“2 When describing the potential legal case Harge is building against Carol, Highsmith doesn't use any of the judgmental midcentury euphemisms I anticipated: “perversion,” “unconventional morality,” “deviancy,” etc. Even when Carol tells Therese about the detective pursuing them, the conversation is oblique and the offense being discussed goes unnamed:

“A detective? What for?”

“Can’t you guess?” Carol said in almost a whisper.

Therese bit her tongue. Yes, she could guess. (206)

While it feels odd as a modern reader to never have any labels applied to their relationship, it's also sort of thrilling to simply have it called love.

Would I recommend it to a queer teen?

Absolutely. It's a tightly plotted, gorgeously written, and very romantic novel with particular appeal to teenagers given Therese's age and the intense nature of her obsession with Carol. Plus, it's fantastic reminder that queer people have always found each other, something young queer people could do with hearing.

How sexy is it?

I'm borrowing the "steam level" system from romance.io, which is as follows:

- Innocent - meaningful glances and perhaps a kiss, but no sex on and off page

- Behind closed doors - at least one intimate scene occurs, but without the reader present

- Open door - at least one intimate scene with the reader present, euphemistic language for act and body parts

- Explicit open door - at least two intimate scenes, explicit language with a variety of sexual acts

- Explicit and plentiful - several explicit scenes, a variety of adventurous acts, dotted throughout the book

Here's an abbreviated version of the main sex scene in the novel:

I love you, Therese wanted to say again, and then the words were erased by the tingling and terrifying pleasure that spread in waves from Carol’s lips over her neck, her shoulders, that rushed suddenly, the length of her body. Her arms were tight around Carol, and she was conscious of Carol and nothing else, of Carol’s hand that slid along her ribs, Carol’s hair that brushed her bare breasts, and then her body too seemed to vanish in widening circles that leaped further and further, beyond where thought could follow. […] And she did not have to ask if this were right, no one had to tell her, because this could not have been more right or perfect. (190)

I'm calling that open door.

Further reading

Patricia Highsmith wrote more than 20 other novels, but none with lesbian or romantic themes, perhaps unsurprising given that she didn't allow The Price of Salt to be published under her own name until 1990. To the general reading public, she's better known as an author of thrillers, and best known as the creator of Tom Ripley, the hedonistic con artist who spends much of the first section of The Talented Mr. Ripley looking at a shipping heir and asking a question posed by queer people since time immemorial: do I want to be him or do him? Famously, Ripley decides he'd rather be (i.e. murder and impersonate) him , which is perhaps why there's some debate as to his queerness.

I can understand the disagreement to a point. In an interview with Sight and Sound, Highsmith said "I don't think Ripley is gay. He appreciates good looks in other men, that's true. But he's married in later books." Well if he has a habit of becoming obsessed with other men and dressing in their clothes, but he ends up married to a woman? Case closed, Patricia. But seriously, people who are entirely straight don't, in my opinion, spend a lot of time contemplating whether or not they're attracted to their same-sex friends, and that goes for fiction and real life. Where there's lavender smoke, there's fire.

Speaking of lavender, I ended up going down a bit of a rabbit hole re: the Lavender Scare when I was looking up some dates that I didn't end up using here. I'm currently in the middle of the audio version of The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government by David K. Johnson, which was published in 2004.3 So far it's a fascinating and occasionally moving look at how Washington became a hospitable place to live and work for queer young men and women and then, within a few short years, became an intensely hostile one, in which hundreds of gay men and lesbians lost their jobs and their reputations.

The 1950s were a fascinating period in gay history, a time of increased visibility due to the publication of the Kinsey Reports and increased scrutiny due to the moral panic that was the Lavender Scare. While it was intended to eliminate homosexuals from public life, Johnson argues that it's partially responsible for a new political consciousness on the part of gay men and lesbians, which saw the formation of the first national gay rights organization, the Mattachine Society, as well as the Daughters of Bilitis, organizations I doubt very much that Carol or Therese would have had any interest in.

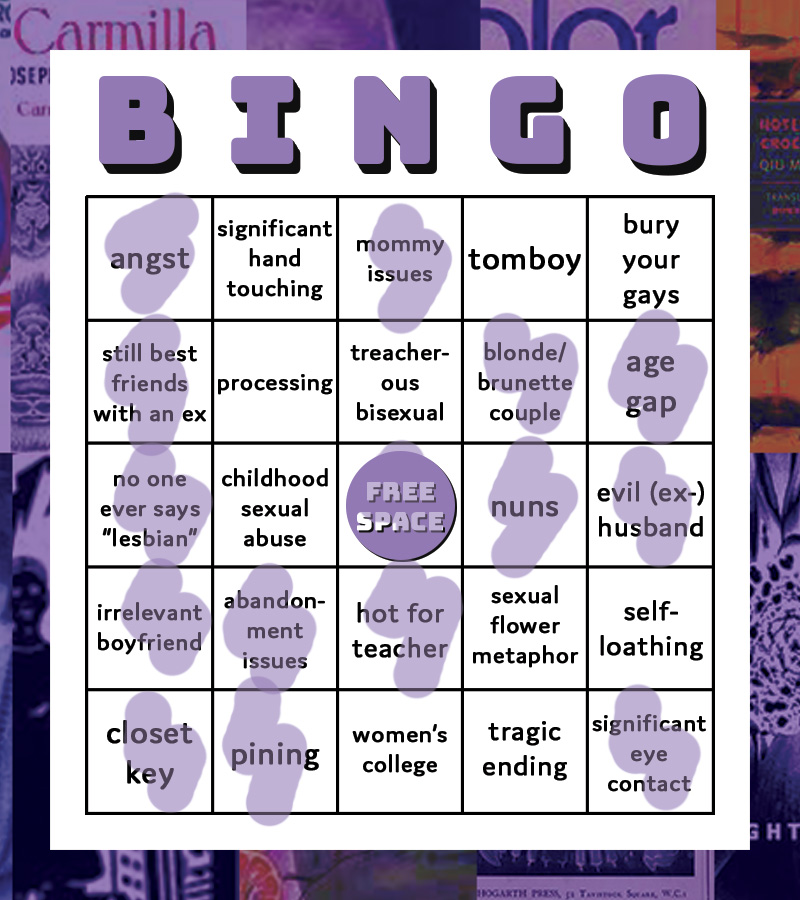

Lesbian classic cliché bingo

Things can get a bit serious when reading lesbian classics, so I thought I'd introduce a game: lesbian classic cliché bingo!

I didn't really get into the mommy issues in this book, but suffice to say that there's a scene where Therese asks Carol for a glass of warm milk4 before Carol puts her to bed for a nap. Combine that with Therese being all but abandoned by her mother and Carol giving up the legal right to see her daughter so that she can live a more emotionally honest life with Therese and… yeah, it's not subtle. The idea that a romantic relationship can be a do-over for a less-than-ideal parental relationship is, of course, nothing new. Nor is the idea that lesbians can have same-sex relationships or familial relationships, never both. For as iconoclastic as Highsmith is in some of her choices in The Price of Salt, here she hews close to convention.

With love from Emily, your local lesbrarian

Works cited, etc.

Highsmith, Patricia. (2004). The price of salt. W. W. Norton.

Highsmith, Patricia. (2008). The talented Mr. Ripley. W. W. Norton.

Johnson, David K. (2019). The lavender scare: The cold war persecution of gays and lesbians in the federal government. [Audiobook]. Tantor Audio.

-

When I was looking into whether or not anyone had written about The Price of Salt as a Bildungsroman I found this article from 2011. If you're interested, a library card login should get you full-text access on JSTOR. ↩

-

Given that inversion referred to gender performance as much as it did to sexuality, this isn't particularly surprising. As Therese puts it. "she had heard about girls falling in love, and she knew what kind of people they were and what they looked like. Neither she nor Carol looked like that."(Highsmith, 79) ↩

-

I realized partway through the introduction that this not only described the Lavender Scare, but essentially introduced it as a concept to the wider American public, which is surprising to me given how frequently it's invoked only 20 years later. ↩

-

Milk that "seemed to taste of bone and blood, of warm flesh, or hair, saltless as chalk yet alive as a growing embryo." (67) Ok, Patricia!!! ↩