People in Trouble (1990)

Two weeks ago I was reading at the lesbian bar when the only man in the room asked me about my book.

“It’s called People in Trouble. It’s about AIDS activism in the late 80’s, but there’s also kind of a love story.”

“Huh, that’s weird.”

I hoped the interaction would end there, if not because his remark was so obviously stupid, then because the mention of AIDS would remind him that he was a man hitting on a woman in a dyke bar. But alas, he kept going and I put my customer service face on until he stumbled out in search of a burrito.

It’s far from original to point out that people go on living their lives during plagues, wars, and all manner of catastrophes. No matter how much trouble they’re in, people will go on living until they can't anymore: not just going to work and buying groceries, but also fucking, fighting, and falling in love. The specificities of how they do so have been the basis for realistic fiction for hundreds of years, from Zola to Tolstoy to Steinbeck to Schulman.

Much of the writing I've read about People in Trouble highlights its documentarian qualities. When she began the novel, Sarah Schulman explicitly set out to write in the realist tradition, modeling her novel on Emile Zola’s Germinal, which recounts the French coal miners strikes of the 1860s. But instead of setting her novel in the recent past, she wrote about the conditions she saw around her—her friends and acquaintances dying from AIDS, real estate moguls getting rich while the poor and homeless slept on sidewalks and begged for change—in real time. Per a conversation with the New Yorker's Peter C. Baker, she started with the details she didn’t want to get lost to time—watch alarm reminders to take your AZT, AL-721 on toast—then moved to the larger truths, particularly that straight America didn't care about the unfolding crisis and did nothing to try and stop it.

Even in writing out that sentence I felt the urge to qualify it somehow—straight America didn't care "for the most part," it did "next to nothing" to try and stop it—but Schulman's version of events is clear. Straight people did not come to meetings, they did not engage in activism, and when they attended AIDS funerals, they were largely confused by what they encountered. In People in Trouble, we see this dynamic through the eyes of three New Yorkers: Molly, a 20-something lesbian working part-time at a movie theater; Kate, a 40-something experimental artist who’s having an affair with Molly; and Peter, Kate's husband, a lighting designer. Molly's friends are dying all around her, and after encountering the leaders of a new grassroots activist group called Justice at a funeral, she throws herself into meetings, demonstrations, and direct action. Peter, for his part, has started noticing gay people everywhere since his wife started sleeping with a lesbian and perceives their more obvious presence—and growing militancy—as a direct threat to him. As he says when he meets Molly for the first time, “people have rights even if they're not gay.” (142)

Perhaps even more insidiously, Kate sees gay people as grist for the mill, mere inspiration for the formally innovative art that she believes is more boundary-pushing and difference-making than anything happening at Justice. Even as she finds herself caring for Molly and enjoying sleeping with her, she doesn't think of herself as gay, instead interpreting the affair as the latest in a long string of “perverse experiences”. (188) She sees Molly as a self-righteous man-hater attempting to drag her into the “ghetto” of lesbianism, whereas she is too free and bohemian to belong to any group in particular.1

I found Kate to be a pretty fascinating villain—striking, self-obsessed, supposedly boundary-pushing yet totally dependent on corporate financing—but Molly is the heart and soul of the novel, largely because she brings the reader into the world of AIDS activism. As the world ignores them, Molly and the other members of Justice—James, Scott, Daisy, Fabian, Sam—do the best they can to heal their community with the resources available to them: robust social networks, library copy machines, determination, and above all, the knowledge that they have nothing to lose. They falsify documents, gather condoms to distribute at Rikers Island, collect information about experimental treatments, and stage attention-grabbing protests at Schulman’s fictionalized version of Trump Tower.

Writing in 1986, Schulman imagined a large, grassroots activist group fighting to help those suffering and dying from HIV/AIDS. ACT UP would be founded the next year and Schulman would join shortly after. By the time the book made its way to print in the spring of 1990, ACT UP had demonstrated on Wall Street, in front of the CDC, and during mass at St. Patrick's Cathedral. Along with the hundreds of others involved in ACT UP, Schulman imagined a world of mutual care and sustenance and put in the work to try to bring it into being, in life and on the page.2 That alone makes People in Trouble remarkable. On top of that, it is funny, sharp, and challenging, particularly so to anyone with assimilationist leanings. Perhaps surprisingly for an unabashedly political novel, it’s also very moving in parts, as when Molly realizes she needs to break it off with Kate because she is, in fact, a dyke who deserves love.

Do they dare speak its name?

Early and often. The marketing copy on the back cover quotes from the book, “Here we are trying to have a run-of-the-mill illicit lesbian love affair, and all around us people are dying and asking for money.” (113) That’s pretty representative of the book at large.

How sexy is it?

Going by the romance.io rating system, I’d call it explicit and plentiful. That being said, the sex scenes are not the main attraction. No one is getting off while reading People in Trouble.

Would I recommend it to a queer teen?

Depends on the teen. The explicitness is whatever, but its subject matter is very adult, which is to say that it concerns things like real estate, hospitals, funerals, etc. The average middle or high schooler might find it boring, but I wouldn't hesitate to recommend it to a college student.

Further reading

Schulman has consistently alleged that Jonathan Larson lifted characters and situations from People in Trouble, which he read and was familiar with, and used them in his musical RENT. Whether or not you believe that's true, it's impossible to know for sure, Larson looked at a crisis that primarily impacted gay men and other queer people and told a story that placed heterosexual characters at the center of that crisis, which is unfortunately pretty standard for media about the AIDS (see: Angels in America, The Normal Heart, Dallas Buyers Club, Philadelphia, The Great Believers, etc.). Schulman writes about what she perceives as Larson’s theft of her work as well as the phenomenon of straight artists cribbing from queer art at length in Stagestruck: Theater, AIDS, and the Marketing of Gay America. For the CliffsNotes, check out one of the many interviews Schulman has done about it over the years.

Lesbian classic cliche bingo

Bingo on a technicality! Kate is a redhead, but I think we can all agree that a redhead/brunette relationship is really just a variation on the blonde/brunette theme. Kate also never claims to be bisexual, but given that she sleeps with a man and a woman during the course of the novel, I feel comfortable calling her both treacherous and a Kinsey 2.

How to read it?

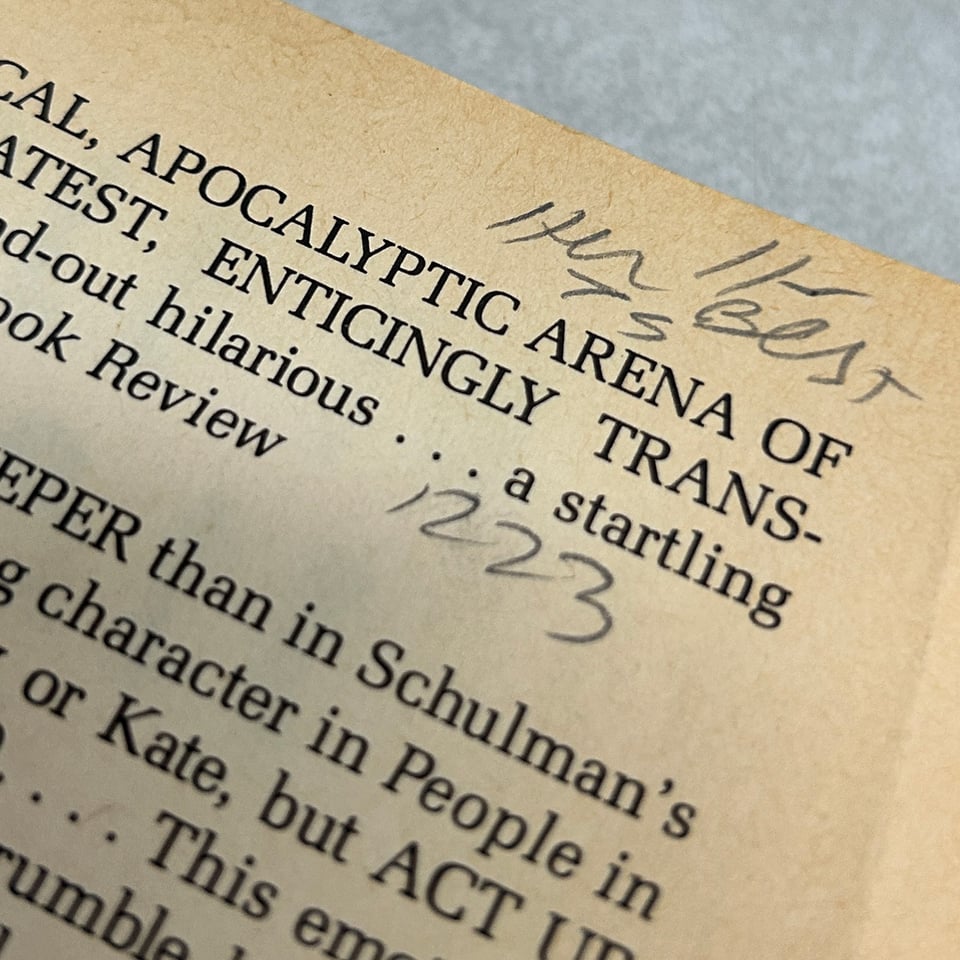

This is the first of many out of print novels I’ll be reading for this project. As such, you can’t just go into a bookstore and buy it and any library copy will likely be reserved for in-building use only. I had the good luck of finding a paperback copy of this book at Troubled Sleep in Park Slope after spending months keeping an eye out for it in used bookstores. While this method has its obvious drawbacks, it also led me to a copy of the book with a used bookmark in it and a note from the bookseller in the top corner of the title page that reads “her best,” so it has its compensatory charms.

That being said, I wouldn't fault anyone for just ordering a copy from Vintage in the UK, which published a new edition in 2019. Otherwise, you can cross your fingers that someone at Dutton decides to put out a new edition stateside, which would make sense to me given how successful Schulman’s nonfiction has been in the past few years, but I’m no publishing professional. Lesbians of booktok, rise up and demand it!

With love from your local lesbrarian,

Emily

Works cited, etc.

Schulman, Sarah. (1991). People in trouble. Plume.

-

One thing I really appreciate about People in Trouble is that Molly barely acknowledges the constant accusations that she hates men. They could be refuted so easily—she puts so much of her energy toward trying to help men dying from AIDS and that desire to help clearly comes from a place of deep love—but they don’t need to be. Addressing an audience at Portland State University, Toni Morrison said that “the function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being. […] None of this is necessary.” While racism and homophobia aren’t exactly alike, I think most if not all forms of prejudice can be used as a distraction. Who cares if they think you’re a man hater? Even if you prove that you aren’t, there will always be another reason to discredit you. Just get on with the work. ↩

-

I’m borrowing this phrasing from a Library Journal interview with Alexis M. Smith that I happened to read last week in which she said the following: “We each, according to our talents and our abilities, need to work toward a future of mutual care and sustenance. Visualize a world in which resources are shared, not claimed by the powerful and privileged few. [...] Then we ask ourselves what we have to offer that world, and begin offering it in this one. One act at a time, in ever-widening circles of connection and care for each other.” ↩