Just wanting to share a good thing

The Color Purple by Alice Walker (1982)

To be completely honest, I’ve been putting off writing about The Color Purple. That’s not the only reason it’s been a while since I last sent one of these—I also came down with the flu and was sick for about two weeks—but it is a reason. At this point I’ve read the book, watched the 2023 film, and read dozens of reviews, articles, and pieces of criticism. The more I read and watched, it seemed presumptuous to think that I have anything of value to say about this book given the sheer amount of commentary and controversy that it’s generated in the four decades since its publication, not to mention its place as a cultural touchstone in the Black community. What could I possibly add? Then I started talking about the book with friends and acquaintances and was struck by the fact that very few of them had actually read it or even knew what it was about, much less knew that it included a queer love story.

And it does, by the way, include a queer love story. You wouldn’t know that from the way many mainstream outlets have covered the book or from the plot summary currently found on Wikipedia.1 You wouldn’t know it from the 1985 film adaptation, which is the way most people have encountered this story. By his own admission, Stephen Spielberg chose to “soften” the “sexually honest encounters between Shug and Celie,” because he feared anything beyond a chaste kiss would cost him the PG-13 rating he was after.2

While the more recent film version directed by Blitz Bazawule includes a duet that ends with a kiss followed by a scene in which Celie and Shug wake up in bed together, it still feels cowardly in comparison to the deeply romantic relationship described by Walker. For what it’s worth, I’m not the only one who feels this way. The critics Brooke Obie and Carmen Phillips have also noted that this new adaptation minimizes the love story even in comparison to the stage version of the musical on which the movie is based.

In the novel, Celie has been sexually abused by Alphonso, the man she believes to be her father, starting when she was in her early teens. Alphonso then marries her off to Mister, a lecherous farmer who expects her to submit to near constant beatings and sexual abuse. Things begin to change when his former mistress, the sensual and wise blues singer Shug Avery, reappears at Mister’s home. When Shug tells Celie that she wants to leave Mister and go back to her home in Memphis, Celie reveals that Mister beats her when Shug isn’t there, and she promises to stay until she knows he won’t go back to his old ways.

It should be said that many of the events of The Color Purple are described obliquely. To be honest, I’m surprised that it’s as popular as it is because while its story is powerful and very well told, it requires some effort on the part of the reader to actually understand it. It’s primarily told through a series of letters to God written by Celie, whose limited education and circumscribed life make it difficult for her to understand much of what happens to and around her, particularly in the first half of the book. Character motivations are implied rather than stated outright, plot events are relayed secondhand or through euphemisms, all of which is completely appropriate for the narrator and the epistolary style. That being said, Celie’s attraction to Shug is stated very plainly,

“Shug come over and she and Sofia hug.

Shug say, Girl, you look like a good time, you do.

That when I notice how Shug talk and act sometimes like a man. Men say stuff like that to women, Girl, you look like a good time.[…]

All the men got they eyes glued to Shug’s bosom. I got my eyes glued there too. I feel my nipples harden under my dress.My little button sort of perk up too. Shug, I say to her in my mind, Girl, you looks like a real good time, the Good Lord knows you do.” (Walker, 85)

This scene comes after Shug teaches Celie about her “button,” and explains to her how pleasurable sex should feel. When the two consummate their relationship several years later, it reads as follows,

Nobody ever love me.

She say, I love you, Miss Celie. And then she haul off and kiss me on the mouth.

Um, she say, like she surprise. I kiss her back, say, um, too.

Us kiss and kiss till us can’t hardly kiss no more. Then us touch each other.

I don’t know nothing bout it, I say to Shug.

I don’t know much, she say.

Then I feels something real soft and wet on my breast, feel like one of my little lost babies mouth.

Way after while, I act like a little lost baby too. (118)

Celie has a number of important relationships with other female characters. Her sister Nettie is the first person to ever love her and their separation sets up the novel’s satisfying conclusion. Her stepson’s wife Sofia teaches her that she can fight back, that when someone is cruel to her she can say, “hell no.” But it’s Shug who teaches her what is probably the most important lesson of the novel, that she is good and worthy, lovable and loved, an expression of the divine spirit present in all things.3 It’s Shug who delivers the speech that gives the book its title,

Listen, God love everything you love—and a mess of stuff you don’t. But more than anything else, God love admiration.

You saying God vain? I ast.

Naw, she say. Not vain, just wanting to share a good thing. I think it pisses God off if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don’t notice it.

What it do when it pissed off? I ast.

Oh, it make something else. People think pleasing God is all God care about. But any fool living in the world can see it always trying to please us back. (203)

Celie learns this lesson from a person who loves her deeply, every part of her in every way. To deny this love is to do The Color Purple, and the message at its heart, a great disservice.

Do they dare speak its name?

Yes and no. There’s no explicit language referring to queer identities or homosexual acts in The Color Purple, which makes sense given what Celie would know of the world. That being said, Shug does say "us each other's peoples now" on page 189, which makes things pretty clear.

How sexy is it?

Per the romance.io steam rating guide, I think this is a pretty clear open door.

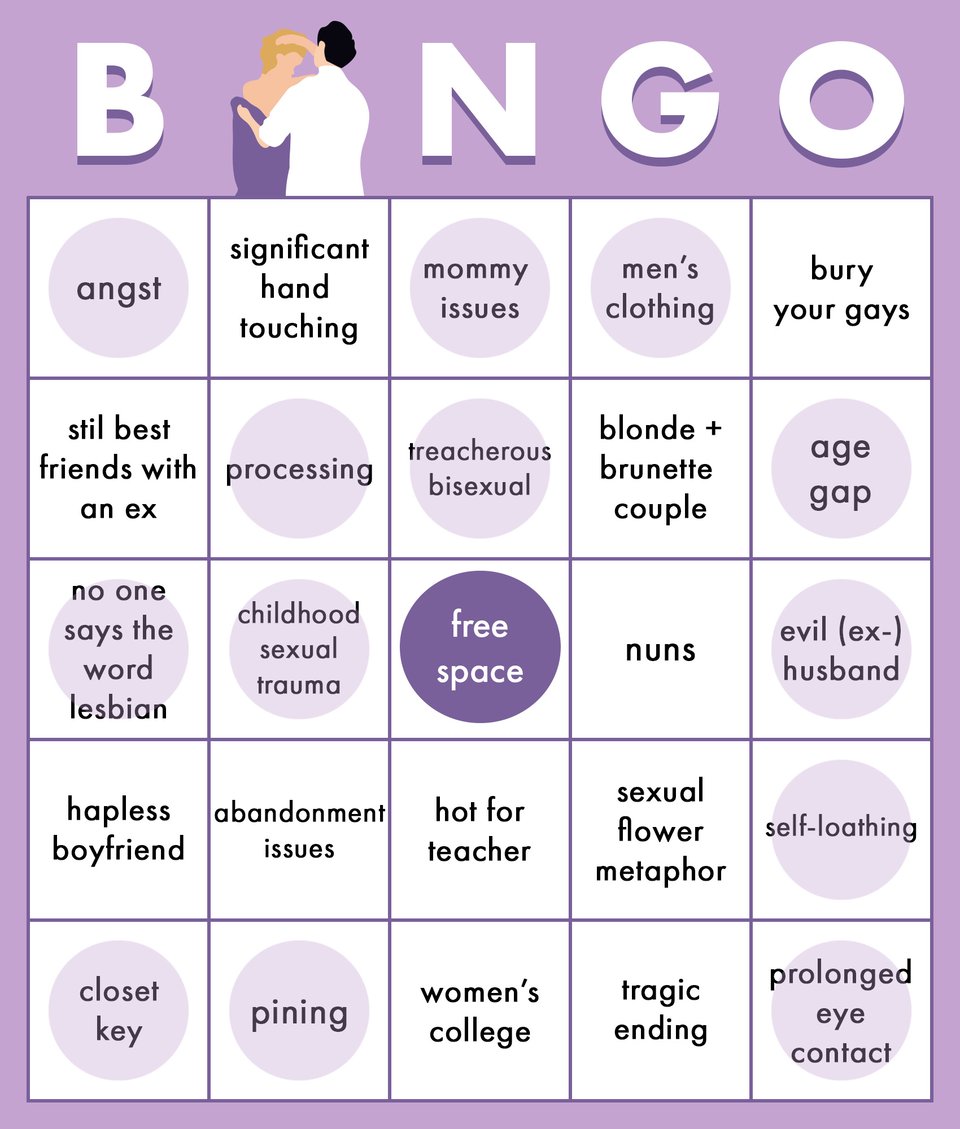

Lesbian classic cliché bingo!

This exercise is objectively too silly to apply to this book, but in the interest of consistency I’m applying it anyway. Close, but no cigar, Alice!

Would I recommend it to a queer teen?

An interesting thing I learned while doing some background reading on The Color Purple is that it was published during a nationwide surge in book challenges, one year after Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico, a Supreme Court case that ruled it unconstitutional for school boards to remove books from school libraries, and the same year as the American Library Association's inaugural Banned Books Week. The first challenge to The Color Purple came in 1984 and according to the ALA, it has remained one of the most banned or challenged books in three consecutive decades 1990-1999, 2000-2009, and 2010-2019. Late last year the Orlando Sentinel reported that it was one of several hundred books removed from Florida schools due to their sexual content, in compliance with HB 1069 and HB 1467.4 All that to say, yes, I would.

While I was home sick I made some updates to the design for this project (please say you like it, I spent so long fighting with the vector tool) and made a Google sheet of the books I'm interested in reading. It's very idiosyncratic and probably incomplete, but significantly easier to navigate and share than my previous notes app list. I'd love to hear any suggestions you'd add to it or opinions on what you think I should read next. Hot tips on where to find lesbian pulps are especially appreciated.

Works cited

Walker, Alice. (1982). The color purple. Pocket books.

-

Don’t be surprised if this changes in the next few weeks. 👀 ↩

-

At the risk of sounding like a college sophomore who just found out about feminism, I think it says quite a bit about Spielberg and the surrounding culture that you can read and choose to adapt a book in which the narrator, a child, is raped on page one, a book that goes on to recount countless instances of violence and abuse as well as the brutality of the Jim Crow era and come away with the impression that what makes it inappropriate for young audiences is a loving same-sex relationship. In the same interview I quote from above, Spielberg admits to directing “the movie he wanted to make from Alice Walker’s book,” and that he simply wasn’t interested in making something “extremely erotic.” To that I say, if you’re going to be such a baby about it, maybe you shouldn’t direct an adaptation of this particular book. ↩

-

This is as good a place as any to point out that Alice Walker has made some remarkably bigoted statements in recent years. In particular, she's made some antisemitic comments of the sort that you’d expect to read on Breitbart, both in her notorious By the Book interview and in a poem called "It Is Our (Frightful) Duty to Study the Talmud". She also may or may not be a TERF. I don’t know if these statements detract from her earlier work. If you think they do, I get that. What I do know is that empathy is one of the most important qualities a writer can possess. Fiction that doesn’t come from a place of trying to understand others—which necessitates seeing them as fully human—will always be hollow. It’s a shame that Alice Walker has allowed her writing, and herself, to be hollowed out in this way after producing The Color Purple, a work of striking and profound empathy. ↩

-

HB 1069 explicitly prohibit instruction on sexuality and gender identity through 8th grade, facilitate the complaint process for parents concerned that their child is encountering and materials that describe or depict any sexual conduct at school. HB 1467 requires school media specialists—professionals who typically have masters degrees, advanced certificates, and state accreditation—to vet every single book that appears in classrooms for “pornographic” or “sexually explicit” content, among other things. These are just two of a number of laws passed by Ron DeSantis that threaten student rights and free speech more generally. Neither is the famous “Don’t Say Gay” Law, HB 1557. ↩