I wish I was back in the army

Women's Barracks by Tereska Torrès (1950)

As I worked on on a draft of this newsletter, I sat at the kitchen table with my roommate, occasionally interrupting her work to read particularly funny or noteworthy passages from Women's Barracks aloud. In one such section, we're introduced to a theory that a woman ought to be able to climax from internal as well as external stimulation. Those women who can only climax from external stimulation are simply “frigid within, and could never be satisfied by men” (Torrès, 112).

Maybe it’s because I’m currently waging a campaign to get my roommate to watch Sex and the City1 or maybe it’s because saying it out loud made me really think about the passage in a way I hadn’t before. Either way, I couldn’t help but wonder, how was it any different than something Samantha would say to the girls over cocktails at Tao?

Claude, who introduces us to the theory above, is a Samantha: worldly, older than the rest of the group, and eager to discuss her sexual liaisons past and present. Samantha may have invented the term "try-sexual," but it could just as easily describe Claude. Much like Carrie, the fun-loving and irresponsible Mickey thinks of herself as being quite daring, but is slightly in awe of the Samanthas of the world. Aristocratic, romantic, self-destructive Jacqueline is obviously a Charlotte. Ann—dependable, slightly masculine2 and by far the most serious about her work—is the Miranda of the group.

Ursula is a bit more complex. Very young and completely petrified of men, she doesn’t map neatly onto any of the women of SATC. As for our narrator Tereska, I could forgive you for thinking she’s another Carrie. After all, she's based on the author herself and the book began as the real-life Tereska Torrès’s diary, but upon reflection, she can only be the viewers: seeing all, judging much, and recounting the experiences of others as if they happened to her firsthand. Of course, Sex and the City mostly takes place in the Manhattan restaurants and clubs of the early, whereas Women’s Barracks is set in 1940's London, where the Corps of French Female Volunteers (CVF) lived, worked, and made the most of being hot young things in the big city.

Do they dare speak its name?

There’s a reason that the marketing copy in my Feminist Press edition of the book credits Women’s Barracks as “the first candidly lesbian novel [emphasis added]” to be published in the US. Torrès consistently refers to three characters—Ann, her partner Lee, and the warrant officer Petit—as lesbians and also uses the term “homosexual” pretty regularly. That alone makes it remarkable for its time, but she goes further and shares her theories on what makes a “true lesbian” versus a “normal" or “real” woman who simply sleeps with other women from time to time. She sets up a binary with one side primarily represented by Ann, a kind of Radclyffe Hall type, and the other by Claude, who was to have been played by Marlene Dietrich in a potential film adaptation (181).

| Lesbians | Normal Women |

|---|---|

| Ann, Petit | Claude, Mickey |

| Atypical gender expression | Typical gender expression |

| Homosexual behavior is innate | Homosexual behavior is learned 3 |

| Deviant behavior sets them apart from "normal" society | Might engage in deviant behavior, but remain part of "normal" society |

| Seeking love, companionship | Seeking pleasure, male attention |

| Serious, tragic | Lighthearted, fun |

| Pursue romantic, sexual relationships with other lesbians | Pursue romantic, sexual relationships with men and "normal women" |

| Cohabitate with women | Cohabitate with men |

There is, however, another character who has a relationship with a woman but doesn't fit neatly into either one of these categories: Ursula. As Tereska describes it, ”Ursula adored Claude, and was attracted to her in a special way she could not explain to herself.” (37) The first time Claude takes Ursula to bed, the younger girl thinks “I adore her, I adore her. And nothing else counted. All at once, her insignificant and monotonous life had become full, rich, marvelous.” (38) The next morning, Ursula buys Claude a bouquet of violets, which are, not for nothing, associated with Sappho.

Are these the thoughts and actions of a person who is just playing games or looking to titillate men? I think not, and yet the narrator takes pains to clarify that by sleeping with her, Claude "initiated Ursula to a vice for which there was no true natural leaning in the girl,” a characterization that doesn't jibe with what's come before it (105).

It should be said that these more judgmental or condemnatory ideas may not reflect what Torrès actually believed. In a 2005 interview included at the back of my edition, she says outright that the narrator’s moralizing was only inserted at the behest of her editor, who feared lawsuits related to the book's “immorality” might impact its success (177). While she didn’t approve of the idea, Torrès allowed her translator (who also happened to be her husband) to add in the “false” moral judgements that would make the book more palatable to a mainstream American audience, creating a winning formula for future lesbian pulp novels.

That being said, I don’t have a way of reading the original French manuscript. That makes it difficult to say where Tereska the author stops and Tereska the morality police begins. After all, she might have been French, but she was a woman of her time and it's easy to remember yourself as being less judgmental or prejudiced than you actually were.

Anyway, this book also introduced me to some slang en français! Based on context clues from the book and some poking around online, it seems like gousse, which is occasionally tossed around by some unnamed members of the CVF, is a French equivalent for dyke.

How sexy is it?

Sexy enough that it was condemned for its "artful appeals to sensuality, immorality, filth, perversion, and degeneracy" by the House Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials in 1952. Chaired by Ezekiel “Took” Gathings of Arkansas, whose legislative record includes voting against any and all civil rights legislation and generally taking orders from Strom Thurmond, the committee was convened specifically to investigate violent comics, girlie magazines, and “immoral” paperback originals like Women’s Barracks. Luckily, these hearings made little to no impact on the book, or to the booming paperback publishing industry. Prior to the hearing, it had sold about 2 million copies and it would go on to sell 2 million more.

That being said, Women’s Barracks is pretty tame to a modern reader. Anything beyond a kiss or caress is just implied. In general, we’re meant to understand the action based on the woman’s reaction rather from any straightforward account of what's happening. This makes it tough to rate on the romance.io steam scale because the reader is technically present for a sex scene between Ursula and Claude, which should make it open door, but they might as well not be given how much of the sex is actually described. As such, I’m calling it behind closed doors.

Would I recommend it to a queer teen?

Sure, particularly if that teen enjoyed Dear America books or other historical fiction aimed at kids. While this book obviously wasn't written as historical fiction, part of its appeal is that it sets out to capture what day-to-day life looked like at a very particular point in time, which makes sense given that it's based on the author's diary. The sex talk is just a plus.

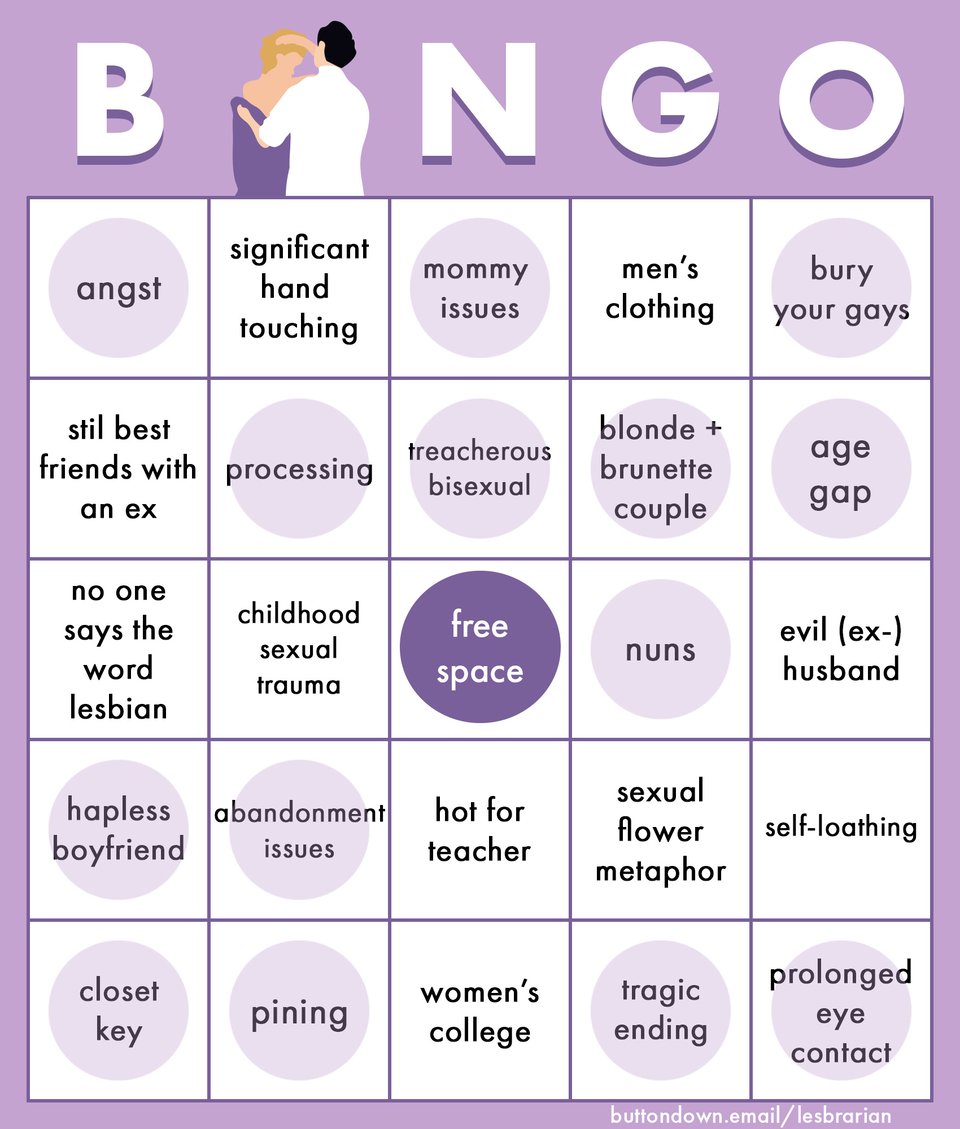

Lesbian classic cliché bingo!

I would have bet anything that this book would get bingo and Tereska didn’t let me down. And to think she didn't get why Women's Barracks is considered a lesbian classic...

Works cited

Torrès, Tereska. (2012). Women's barracks. Feminist Press.

-

She's watched all of The Bold Type and Younger but doesn't even know who Mr. Big is. I swear, Gen Z has no respect for history. ↩

-

Read: a lesbian. While it's no longer the latest idea in sexology, we're still working with the idea that people who experience same-sex attraction are “inverts,” whose bodies and minds somewhat resemble those of the opposite sex. I'll dig into this more when I eventually suck it up and re-read The Well of Loneliness. ↩

-

In one memorable passage on page 72, Torrès compares Claude’s decision to "learn to" sleep with women to her decision to begin engaging in group sex or start smoking opium. ↩