Ecce lesbianae

The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For by Alison Bechdel (2008)

Happy Lesbian Visibility Week! I’d be lying if I said I planned to put out a newsletter about any book in particular during this week–I’m not quite that disciplined or organized–but The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For happens to be perfectly on-theme.

Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For started out as a loosely collected series of cartoons about young, urban lesbians published in queer and feminist newspapers. The very first edition from 1983—you can check it out on Bechdel’s blog here—is just a single panel with no named characters and a randomly assigned number, “plate 19.” The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For starts in 1987, by which time Bechdel was numbering her full-page strips in earnest and had settled on a main cast of six.1

The central character is Mo, a politically-minded, neurotic, underemployed clerk at the local feminist bookstore, Madwimmin Books. Her fellow bookseller—the gender-bending, over-sexed Lois—shares a house with Ginger, a struggling academic, and Sparrow, a crunchy “bisexual lesbian” who works with victims of domestic violence. Mo’s college girlfriend and current best friend is Clarice, a personally cautious and politically radical environmental lawyer and now partner to Toni, an accountant and freedom to marry advocate who’s still not out to her family. Bechdel follows these women—plus a rotating cast of girlfriends, lovers, colleagues, students, and friends—across 21 years of hooking up, breaking up, working, protesting, and discussing the issues of the day, from the optimism of the early Clinton years to the crushing comedown of the second Bush administration.

The concerns of the comic are wide ranging. Explaining how the strip gives equal weight to the dykes’ personal and political concerns, Bechdel has described DTWOF as “half op-ed column and half endless serialized Victorian novel.” Instead I’ve found myself thinking of it as a soap opera for people who read theory, or else feel like they should be reading theory and nod knowingly when someone invokes Judith Butler or The Epistemology of the Closet. It’s a lower-brow comparison, but I think it gets at how much fun these cartoons are, even though they were created with a lofty goal in mind.

To that point, Bechdel writes in the introduction to The Essential DTWOF that when she started publishing her cartoons,

“We had no L Word. We had no lesbian daytime TV hosts. We had no openly lesbian daughters of the creepy vice president. We had Personal Best and we liked it. I saw my cartoons as an antidote to the prevailing image of lesbians as warped, sick, humorless, and undesirable or supermodel-like olympic pentathletes, objective fodder for the male gaze. By drawing the everyday lives of women like me, I hoped to make lesbians more visible not just to ourselves, but to everyone.”

I love the way DTWOF presents lesbians—as wonderful, infuriating, complex human beings—but I also love it because it’s fucking funny. While reading in the park, I laughed out loud at Mo’s over the top neurotic antics and her cynical and ever-relevant take on pride. While reading at work, I cried when Ginger’s beloved dog got sick and died. And while reading in my bedroom, I felt real loss when Madwimmin Books was pushed out of business by chain bookstores like Bounders Books and Muzak. The Essential DTWOF didn’t elicit these emotional reactions didn’t arise because I could see myself in it, but because it’s thoughtful, clever, and well-drawn, increasingly so as time goes on.

Put differently, while I think representation and visibility are valuable—that’s sort of the underlying premise of this newsletter—I also think that boiling books or other works of art down to those qualities does them a disservice. Similarly to how I think describing a book as “important” makes it sound like assigned reading, I think labeling a book as being “good representation” makes it sound boring as hell, when representing the full humanity of a person or group ought to be anything but.

Do they dare speak its name? 💬

lol, yes. This is just a hunch, but I strongly suspect that part of the reason The Essential Dykes to Watch Out For has never been as popular as Fun Home or gotten much of a bump from its success is because the title includes the word “dyke.”

How sexy is it? 🔥

The Essential Dykes to Watch Out for has by far the most sex of any of the books I’ve read for this project so far. A sex act is depicted—and I mean depicted, not just narrated or described by the characters—pretty explicitly in the first ten pages of the introduction. While sex isn’t the main event, the book is very frank about the role of sex in these women’s lives and the early strips in particular have a lot of nudity. I’d call it explicit and plentiful according to the romance.io steam rating guide.

Would I recommend it to a queer teen? 👍👎

Enthusiastically! In the introduction, Bechdel notes that she was horrified when she started receiving mail from young lesbians that her characters were their role models, but I think you could do a lot worse. The dykes are certainly flawed—they whine, they gossip, they cheat, they whine some more—but they also grow and change, which is to say that they’re like real people.

Lesbian classic cliché bingo! 🏳️🌈

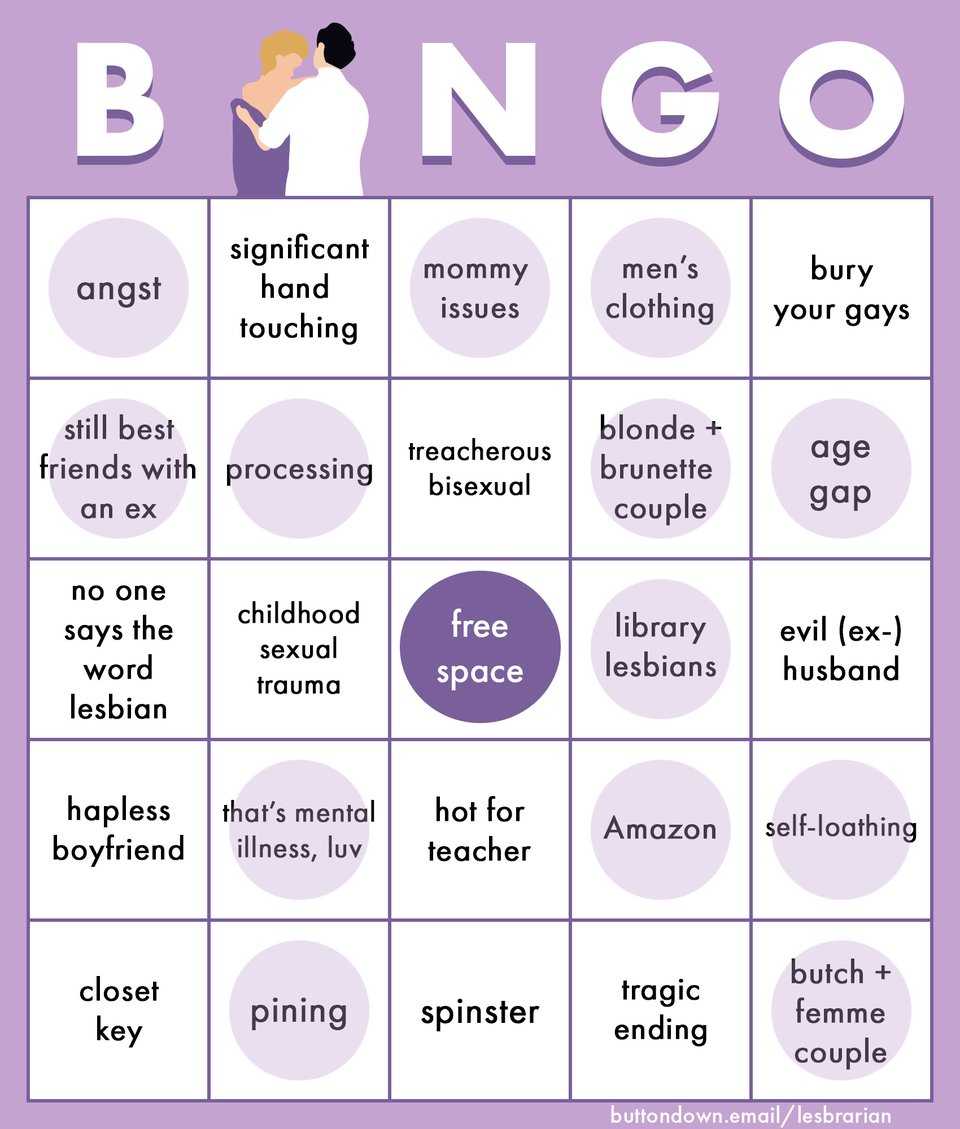

I’ve decided to make some tweaks to my bingo board, partially inspired by a book I just finished called Suffering Sappho! Lesbian Camp in American Popular Culture by media and gender studies professor Barbara Jane Brickman. Looking at how the “lesbian menace” was depicted in midcentury popular culture, Brickman identifies five major lesbian camp figures: the sicko, the monster, the spinster, the Amazon, and the rebel. Setting the monster (too genre-specific) and the rebel (too general) aside, I’ve added that’s mental illness, luv2, spinster, and Amazon to the board.

The other new square, library lesbians, comes from my growing fascination with how many of these books include a pivotal scene that takes place in a library, involves a librarian, or that centers on a character reading a book. I’m obviously primed to notice these scenes because of my job and interests, but I’m beginning to suspect that authors are primed to write them as well. Both The Well of Loneliness and Spring Fire include scenes in which a character is introduced to the concept of female homosexuality through reading a book in a library. People in Trouble has a librarian/organizer in its cast of characters and Mo from Dykes to Watch Out For eventually goes to library school. DTWOF also includes a library hookup in which Mo’s girlfriend Sydney suggests they “do it in the HQ 70’s,” which probably wasn’t written for me specifically, but it feels like it was.3

Thanks for reading,

Emily, your local lesbrarian

-

I understand why Bechdel decides to start the collection when she does, but an interesting result of this choice is that the single most famous strip of the comic–the one that introduces the Bechdel Test—isn’t included. I first encountered the Bechdel Test in early 2012, when scholar Anita Sarkeesian posted a video titled “The Oscars and the Bechdel Test” to her YouTube channel. The Google Trends data bear out that this is how many others first discovered the test as well. The number of searches for the term “Bechdel test” spiked in February 2012, then grew steadily over time, signaling an increased awareness of and interest in the idea. I have to think that if The Essential DTWOF were published today, or any time after 2012, “The Rule” would be included as an appendix. ↩

-

The sicko refers to the mentally ill lesbian, and Brickman’s prime example of a work that uses this trope is Spring Fire. ↩

-

The section of the Library of Congress catalog devoted to “sexual deviations,” natch. ↩