A creature of intense passionate feeling

I Await the Devil's Coming by Mary MacLane (1902)

Mary MacLane is a genius—at least according to her. In the 176 pages that make up I Await the Devil’s Coming, the word “genius” appears nearly 100 times, mostly in reference to the author herself. At various points she describes herself as “a rather plain-featured, insignificant-looking genius,” “a genius starving in Montana in the barrenness,” and “a genius with a wondrous liver within.” When referencing her education, she writes that in addition to the Latin, French, and Greek she learned at school, she possesses “peripatetic philosophy that I acquired without any aid from the high school; genius of a kind, that has always been with me.”

While she compares herself to other “genius” writers—Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot, and the diarist Marie Bashkirtseff—she acknowledges that she is “not a literary genius.” Instead, her “genius is analytical. And it enables me to endure—if also to feel bitterly—the heavy, heavy weight of life.” She returns to this idea, that her genius is tied to her deep capacity for emotion, on the final page of the book, writing,

I am not good. I am not virtuous. I am not sympathetic. I am not generous. I am merely and above all a creature of intense passionate feeling. I feel—everything. It is my genius. It burns me like fire.

In theory, I Await the Devil’s Coming is a diary, the “record of three months of nothingness” in the life of a 19 year-old living in Butte, Montana. The original title under which the book was published, The Story of Mary MacLane, reflects as much, but there is very little real space devoted to the day-to-day events of MacLane’s life. Instead she’s focused on her own mind, her own genius as she sees it. Rather than calling her book a diary, MacLane deemed it a portrayal, by which she meant that it was nothing more than “inner life shown in its nakedness.” She explains further that in writing her book,

I am trying my utmost to show everything—to reveal every petty vanity and weakness, every phase of feeling, every desire. It is a remarkably hard thing to do, I find, to probe my soul to its depths, to expose its shades and half-lights.

Not that I am troubled with modesty or shame. Why should one be ashamed of anything?

Shuffle the syntax and update the vocabulary a bit and I think you could stick those sentences—particularly that last one about modesty and shame–in a Tumblr post, an Instagram caption, or an entry on a mommy blog. Several other literary Emilys have observed that MacLane’s powerful ego, eagerness to provoke, and everyday subject matter–pages are devoted to topics like her dreams, her crush, her loneliness, and the art of eating an olive–would have made her extremely well-suited to writing for the social internet.1 Even so, I think it’s worth restating here: Mary MacLane was born to blog. No matter what topic she writes about, her subject is always herself. Calling out from her lonely life in Montana, she begs the reader to notice her, to validate her ego, to see that she is more than her plain exterior—or her sex—would indicate.

Writing about oneself for public consumption is so standard in 2024 that while it might occasionally lead to some self-consciousness on the part of the writer or some agita from the digital commentariat2, most of us do it anyway, and do so regularly to little fanfare. In 1902 it caused a sensation; I Await the Devil’s Coming sold over 100,000 copies in the first month after its release and young women across the country formed Mary MacLane clubs to discuss and appreciate their new favorite book and its iconoclastic author. Perhaps they saw themselves in MacLane: her dramatic moods, her intense passions, her deep-seated sense that she was somehow above her surroundings, her belief in her own worthiness. Or maybe it’s just that they also had crushes on their English teachers, who can say?

Do they dare speak its name? 💬

No, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t any lesbian content in this book. While MacLane often longs to meet and marry the Devil, the only person for whom she expresses any true romantic or sexual feeling is her former literature teacher Fannie Corbin, who she mostly refers to as the anemone lady.3 We’re first introduced to her as MacLane’s only friend, though she has since left Butte for unstated reasons and the two have presumably lost contact.

MacLane writes that she loves the anemone lady with “a peculiar and vivid intensity, and with all the sincerity and passion that is in me.” She fantasizes about spending her life with the her in a house on a mountain, which would fill her with “happiness softly radiant.” I understand that people used to write about their same-sex friendships in very romantic terms—frankly I’m not sure we ever stopped doing that, just look at any hot girl’s Instagram comments from her friends—but there really is no heterosexual explanation for the following:

My love for her is a peculiar thing. It is not the ordinary woman-love. It is something that burns with a vivid fire of its own. The anemone lady is enshrined in a temple on the inside of my heart that shall always only be hers.

She is my first love—my only dear one…

I feel in the anemone lady a strange attraction of sex. There is in me a masculine element that, when I am thinking of her, arises and overshadows all the others.

“Why am I not a man,” I say to the sand and barrenness with a certain strained, tense passion, “that I might give this wonderful, dear, delicious woman an absolutely perfect love!”

In her third book I, Mary MacLane (1917), MacLane devotes an entry to the idea that “all women have a touch of the Lesbian.” She explains that

“There are aggressively endowed women whose minds are so bent that they instinctively nurture any element in themselves which is blighting and ill-omened and calamitous in effect. There are some to which the natural inhibition of their own sex is lure and challenge. There are some so solitary by destiny and growth that the first woman-friend who comes into their adolescence with sympathy and understanding wins a passionate Lesbian adoration the deeper for being unrealized.”

She eventually says outright that she’s no exception to the rule, in case it weren’t clear enough from that last sentence, which could have been written about her own relationship with the anemone lady. What’s more, in the years since writing I Await the Devil's Coming and moving east she wrote that she has “lightly kissed and been kissed by Lesbian lips in a way which filled my throat with a sudden subtle pagan blood-flavored wistfulness, ruinous and contraband.” Happy for you, Mary.

How sexy is it? 🔥

By the standards of 2024, not particularly. Even in her most heated moments, when she imagines meeting the devil, she only asks that he embrace her hard and kiss her “with wonderful burning kisses.” Scandalous for sure, but it barely merits the lowest rating on the romance.io steam rating, glimpses and kisses.

Would I recommend it to a queer teen? 👍👎

More strongly than I would to a queer adult! Mary MacLane’s combination of world-weariness and solipsism reminded me so strongly of my young self that it was almost tough to read. While the teenager might be a modern invention, the teenage condition clearly is not.

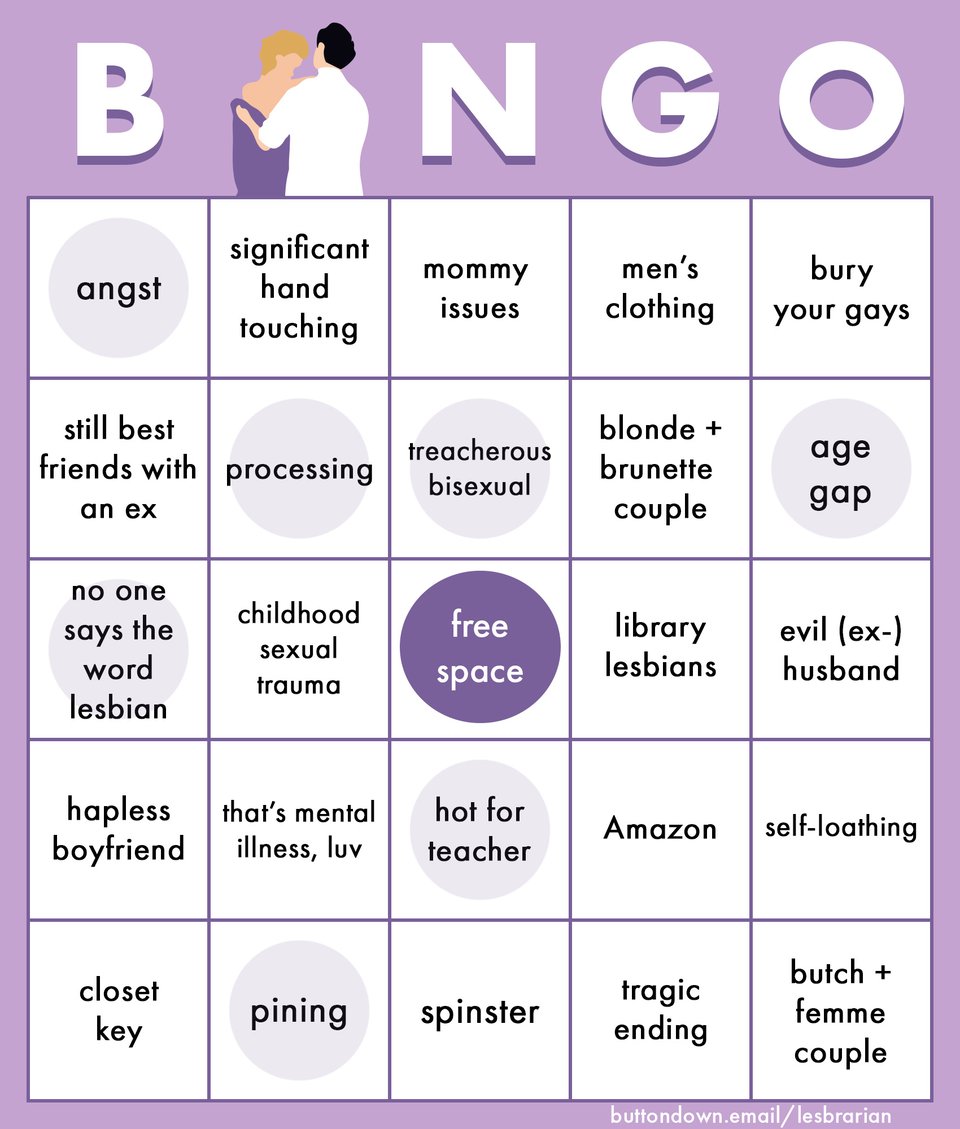

Lesbian classic cliché bingo! 🏳️🌈

Yeah, this wasn’t really meant for books like I Await the Devil’s Coming, which doesn’t have a love story or even much of a plot to speak of. That being said, in the tradition of queer teens for at least the last 100 years, she gets a decent amount of mileage out of her unrequited crush on her English teacher here.

How can you read it? 📖

For those of you looking to save money, you’re in luck: all of Mary Maclane’s work is in the public domain and available on Project Gutenberg and the Internet Archive. If, like me, you prefer do your reading on paper, there’s also a paperback edition from Melville House, which I happened to find a used copy of at Troubled Sleep.

Further reading 📚

I first encountered Mary MacLane in emily m. danforth’s Plain Bad Heroines, which takes its title from a particularly interesting passage in I Await the Devil’s Coming. A Mary MacLane club of the type I mentioned above features prominently in the book, which spans two timelines, one in 1902 and one in the present. The book’s plot is quite complicated—the present day storyline takes place on a movie set of a film adaptation of a book about the events of the 1902 storyline, phew!—and includes a fair amount of metatextual commentary, so I won’t take the time to do a full summary here. Suffice to say that it’s a wonderful, mostly fictional book about Hollywood, the recovery of queer history, and the ethics of telling someone else’s story, so I’m glad that it lead me to some actual, non-fictional queer history in the form of Mary MacLane.

Sorry for the long absence and thanks for reading,

Emily, your local lesbrarian

Is Emily the most literary name a girl can have? I think its brand has been diluted a bit over the past few decades because of how common it is, but given that the most famous celebrity Emily is probably Emily Dickinson–Famous Birthdays be damned–not to mention Emily Brontë, plus iconic children’s literature characters like Emily of New Moon, and Emily-Elizabeth of Clifford, I think there’s a strong case.

See: the last few discourse cycles related to articles published in The Cut.

Flower, not sea creature.