lend me ur eyes 083

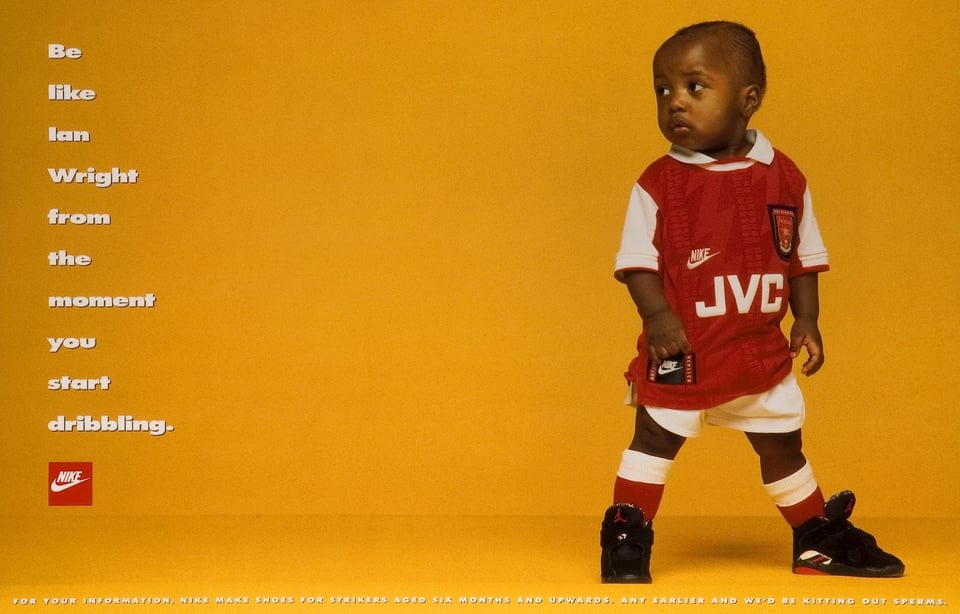

I managed to get tickets for three Arsenal games this month. I hadn’t been to a live (men’s) game since around 2005, so that first return felt momentous and wrapped up in all kinds of sensations and emotions, some easy to identify and others harder to pin down. Arsenal Football Club has a lot of associations for me; the club is tethered to many memories and moments in my life, but also to various markers or classifiers: of identity, of place, of feeling, of time. I’ve supported Arsenal since I was young, through the good times, bad times, and, recently, good times again. As a kid, my first favourite player was Dennis Bergkamp, but I can just about also remember watching Ian Wright, who would have been ending his career at Arsenal when I was six or seven at most. I chose the team because my friend’s older sister, a season ticket holder, told us we both had to support Arsenal… or else. So we did; dad bought me a JVC shirt.

The club has always felt near, even before I started living ten minutes walk from the stadium. In the 2000s, my milkman in Enfield delivered to the team and he would talk to my dad and I about games, delivering rumours he would be hearing at the training ground. He gave me a ball signed by the entire 2001/2002 season first team, which, though now deflated, I still have. Every Saturday morning we would see Pat Rice at Sainsbury’s in the Highlands Village, doing his weekly shop. We saw Arsene Wenger once too, walking in Muswell Hill with a woman who may or may not have been his wife. “He’s taller than he looks on TV,” my dad said, starstruck. “And more handsome too.” Later on, it was possible to spot Cesc Fabregas at Miracles Cafe in Cockfosters. None of these things would probably happen now.

I’ve been reading Black Arsenal, an essay collection and photo book edited by Clive Nwonka that explores Arsenal’s connections to Black communities and culture, covering the history of Black players from David Rocastle to Ian Wright to Bukayo Saka and beyond, the club’s community work in Islington, various bits on cuisine and culture, and the diversity of a fanbase that, the book argues, is, or at least was, unique compared to other Premier League teams. At primary and secondary school, everyone supported either Arsenal or Spurs. Most of the Black kids supported Arsenal, while the white kids were largely Tottenham fans. Amongst the Turkish and Greek groups, it was a pretty even split, but in any case, Arsenal has always seemed to me to be associated with where I’m from and what that means. As well as humour, one of those things is multiculturalism and a kind of localised sense of belonging that comes from being connected not by ethnic or social background, but by an understanding of, and attachment to, a place and its culture, which itself comes from the blending and mixing of lots of small different worlds.

One of the pieces in the book is an interview with Femi and TJ Koleoso from Ezra Collective, both of whom are from Enfield (and went to school with CQ’s brother, also an Arsenal fan). Femi talks about the idea of the inherited connection to the club, him being signed up to be a Junior Gunner by their Nigerian uncle on the occasion of his birth. “I don’t have any connection to the word ‘English,’ or to the word ‘British,’” he says. “I have a connection to the word ‘London,’ But we don’t necessarily have a flag that represents that. For me, Arsenal became that flag. This is why I love that I’m a North Londoner. I love that I’m an Arsenal fan.” Obviously I can’t relate to being a Black Arsenal fan, but I do appreciate the multiculturalism of the club and the area it is situated within. I also very much get his point about being ideologically attached to North London but feeling alienated from Britain as a whole. When I walk along the Holloway Road on a match day and see all the fans of different ages, races, and genders unified by the red shirt and scarf, I do feel something resembling belonging, a reminder of where I am from and what that place represents and values: plurality, inclusion, and a hatred for the division that racism sows. This was something felt too when Jeremy Corbyn stood successfully as an independent candidate in Islington this year, running in opposition to a Labour Party, and to a wider country, that cannot be said remotely to stand for those same things.

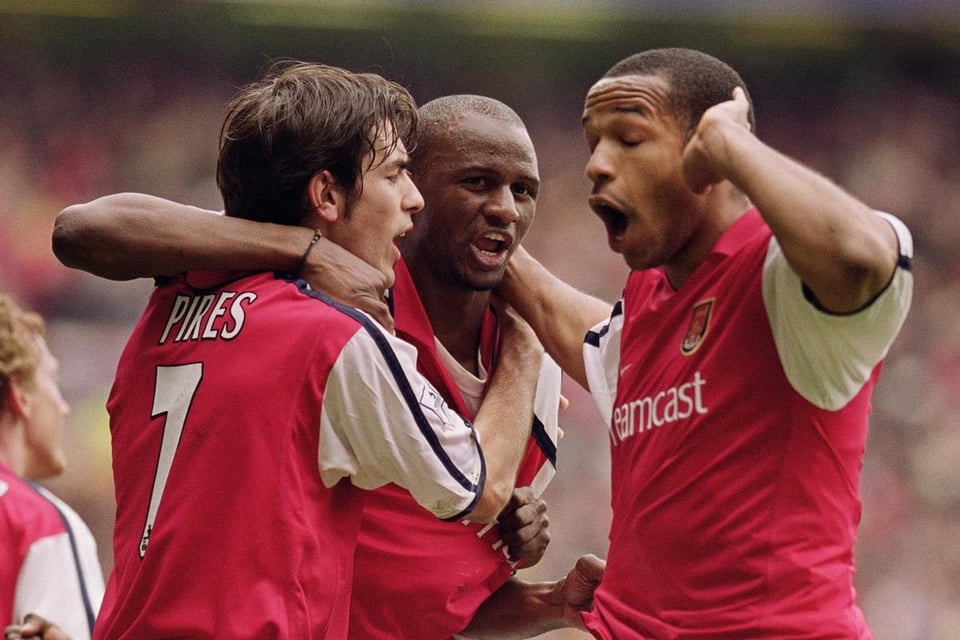

I also connect Arsenal, probably wrongly, with a kind of beauty, born from watching Arsene Wenger foster a kind of flowing, freeform style of football associated with players like Bergkamp, Robert Pires, and, of course, Thierry Henry. None of that was on display at the games I went to, but it didn’t matter too much. We still had inspirational sentiment to generate and corners to celebrate, singing chants of “Set Piece Again, Ole Ole” irregardless of whether or not a goal went in. At the Manchester United game, I was sat in between two young men, a fairly quiet young Black guy from Stratford who filmed every corner on his phone just in case a goal went in, and a gregarious white Irish guy who had moved to London from a small town near Dublin two months ago. One of them had got their ticket as a third choice backup via a friend, while the other got it on the fan ticket exchange like me. Behind us were a few older season ticker holders, who we also befriended without intending to. At one point, when one of them made some kind of joke about William Saliba that was phrased in a way that amused me, I turned my head back and gave him a knowing look. He liked that and slapped me affectionately on the back, a gesture through which men who don’t know each other connect, a kind of momentary contact high that is more intimate than a high five but not quite as full-on as a hug. It felt really good, like a confirmation that I belonged there and that he understood I was a real fan, not some interloper trying to fit in by wearing the right shirt.

At the Everton game, the thing I actually liked the most was the walk into the stadium. I run round the stadium every week, ducking in between personal trainers leading street sessions and groups of people dancing to disco on roller skates, so it is familiar terrain. But this time I was coming in from Finsbury Park rather than the Holloway Road. It was still light and the roads were filled wide with fans, many of them families, walking together past the old Highbury Stadium location and through the rear entrance of the ground. As well as a group of kids from Gillespie School who were singing carols and collecting for charity, it was great to see the houses along the way that had turned their front gardens into grill kiosks, selling home-cooked burgers and hot dogs to passing fans, plus that one house that acts as a supporters clubhouse at the end of St. Thomas’s Road.

There’s another good piece in the Black Arsenal book written by Stardious Christie, who operates a Caribbean food stand outside the Arsenal ground. In that, he describes going to Arsenal away games at Chelsea in the ‘70s, wearing snakeskin boots and silk shirts, and beating up National Front members giving out leaflets outside their ground. He also talks about Black and white fans coming together to batter racist Millwall fans at home games in 1988 and 1995, making a conscious effort to “show them what we were about.” What I saw was almost comically far from what he describes, those aspects of violence and hooliganism that live football used to be associated with, but there was still something that felt old fashioned and nostalgic about it, a world away from the commercialism and cynicism of the modern Premier League and closer to what I remember faintly about going to Highbury in the early 2000s with my dad. It is stupid to feel sentimental about fast food trucks and scarf-sellers, but, within a city that is increasingly soulless, the whole scene struck me as geographically specific and culturally authentic, while also touchingly naff - like something out of Fever Pitch.

Despite the flatness of the actual football, both outings felt amazing, like a homecoming to a place I had potted memories from going to as a child, different but mostly the same. Loud, brightly lit, and larger than life, a match at the Emirates feels like gathering in a big tank with 60,000 friends, all singing, shouting, and offering unsolicited advice to the little football men down below. Togetherness, camaraderie; shared elation and frustration; momentary explosions of catharsis and joy. All awareness of the mundanity of normal life suspended for 90 minutes of communion under the floodlight glow. Tonight I go again.