Demolition by Neglect

“Demolition by neglect” occurs when the owner of a historic property allows it to decay beyond repair. The phrase is a warning call to built heritage activists across Canada and beyond. The National Trust for Canada keeps a list of heritage structures from across the country that have been lost and demolition by neglect is often a contributing factor.

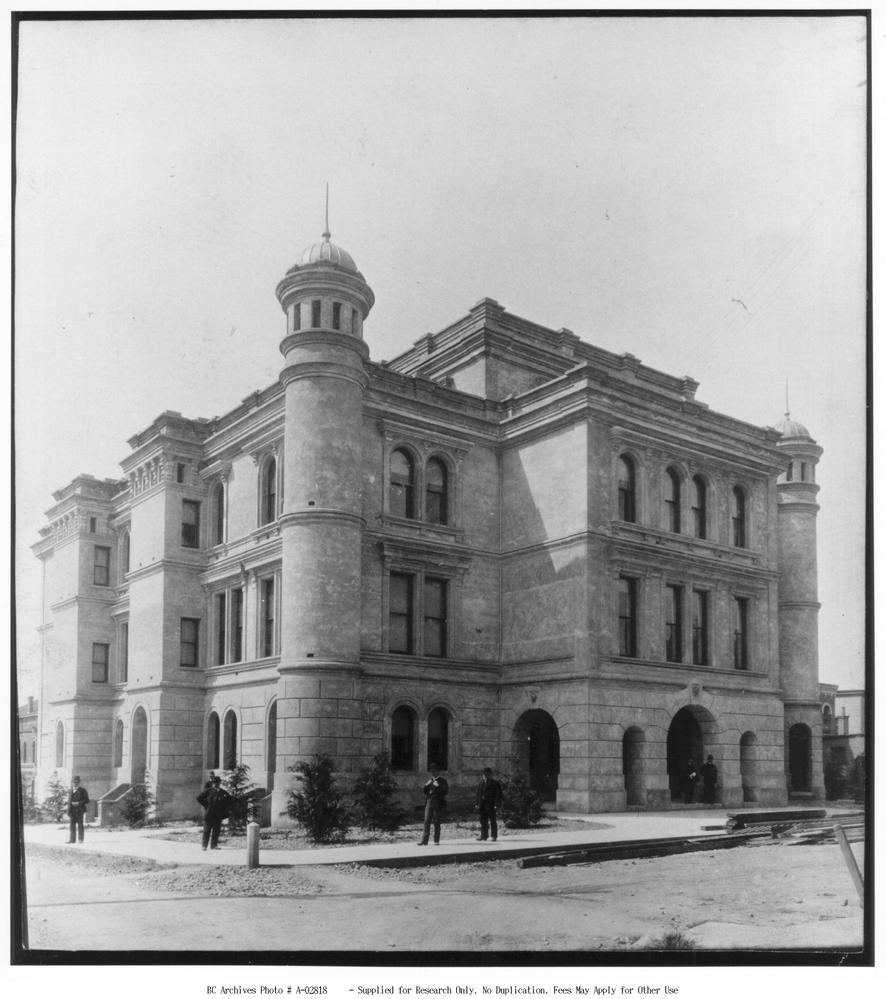

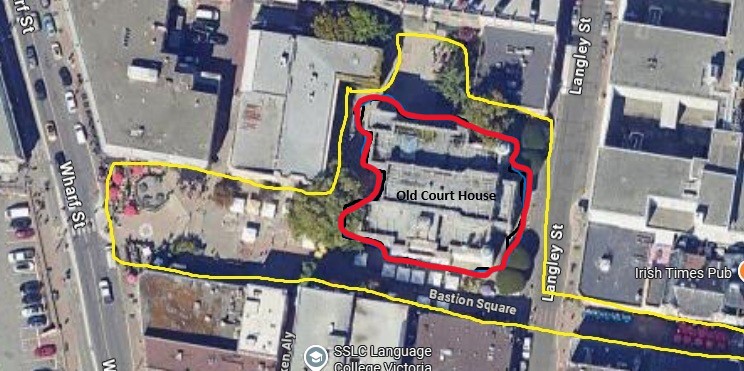

There's a prominent example of this phenomenon underway in Victoria. It is a building that looms large over one of Victoria’s public squares: 28 Bastion Square. AKA the former Maritime Museum. AKA Victoria Law Courts. AKA The Old Court House.

The Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada has designated 28 Bastion Square as being nationally significant. The designation reads, in part:

The Former Victoria Law Courts was designated a national historic site of Canada in 1980 because: it is representative of the judicial institution in British Columbia; this first major public building constructed by the provincial government after union with Canada marked an important stage in the evolution of British Columbia’s court system and the start of a programme to erect permanent court houses in judicial districts throughout the province; its unique design used a composite of various stylistic elements and was determined by the utilitarian priorities of the court house function.

The federal government, however, does not own the building. The owner is the Province of British Columbia who closed and boarded up the building in 2015.

A Decade of Neglect

The reasons for the closure of the Old Court House are unclear. The province kicked out the Maritime Museum in 2014 (the tenant since 1965) and closed the building shortly thereafter, apparently due to some structural concerns. However, in a Times Colonist article from 2018, the person overseeing the court house for the Ministry of Citizen Services’ Real Property Division claimed the building was in pretty good shape:

‘It is impressive how well the building has performed over 130 years,’ he said. ‘Our engineers are telling us that the core structure, the bones of the building, are still good enough to last and last for years to come…There are sections where water has infiltrated into the wall space. It’s a wood-frame building with masonry on the outside, and then what happens is the plaster gets moisture on it…Usually there’s going to be mould present within the plaster, so they strip away sections to expose the brick and tear out the water damage.’

That was almost eight years ago. I have a fair bit of experience with heritage buildings and living in buildings and there is one thing I know for sure: Water infiltration is bad.

Freedom of Information

Early in 2025, I received a response to a Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) request about the court house. In my view, the documents received show a directionless bureaucracy and unwilling ministers who toss the future of the building back and forth like a hot potato.

In late 2019, the province put out a Request for Information (RFI) seeking ideas for what to do with the building. All proposals submitted to the RFI were eventually rejected by the province due to their incompatibility with the financial and heritage constraints.

The problem with the future of the court house is the same one that I ran up against as director of Point Ellice House Museum and Gardens (also a provincial heritage property): No money, no vision.

Based on information available in the FIPPA documents, the cost of keeping the building shuttered is about $170k annually (including taxes, maintenance, and operations). The ministry also noted that seismic upgrading of the building would cost around $20.5M (2018 estimate).

No surprise then that the province had difficulty finding a reasonable proposal. It’s a bit like crashing your car and then putting a notice in the paper that you're willing to rent the car out to someone if they take on all the costs of fixing it and maintaining it.

Neglect, Ignorance, or Both?

Although 28 Bastion Square is a National Historic Site and is listed on the City’s heritage registry, it is not a building with a provincial heritage designation. In other words, the province, as owner, has no obligation to retain the building. The idea of a provincial designation was rejected by bureaucrats in 2019 who recommended to the minister that it not be pursued because it would cost $75k in consulting fees.

Among the more than 60 pages of documents in my FIPPA request, this advice to the minister stood out to me. The primary tool for a heritage designation is the creation of a Statement of Significance. However, there is already a Statement of Significance for the building, one that was created in 1980 when the building became a National Historic Site.

Did the bureaucrats at the Ministry of Citizen Services not understand how the heritage designation process works? That seems unlikely. Perhaps they understood it perfectly well and recognized that provincial designation would be a barrier to selling, gutting, or demolishing the Old Court House. I can only conclude that demolition by neglect is the unofficial policy that guides the ministry’s approach.

What about the City of Victoria?

“Why is a major heritage building at the centre of a once bustling downtown square allowed to be shuttered by government for a decade?”

That’s the question I asked City of Victoria councillors during a presentation in 2024. After my three minutes ended, there was some agreement from council that this was a good question to ask, but that has been the extent of any obvious engagement on the matter from the city.

City council talks a lot about reviving downtown. Bastion Square and Centennial Square were both created in the 1960s and are vital parts of the city’s public realm. Centennial Square is being “revitalized” – though the city council recently took money from the project to give the police an additional $10M to address “street disorder.”

If a safe and inviting public realm filled with arts and culture is essential for Victoria – as city councillors claim that it is – I find it curious that there’s no appetite to compel a negligent landlord to take action and breathe life back into Bastion Square.

A City Museum?

Based on the currently available information, it seems the provincial government is considering only two options for 28 Bastion Square:

Provide the building to private developers, likely to result in year another example of heritage facadism in Victoria (e.g.Ducks Building)

Allow the building to remain closed, likely to result in demolition by neglect.

If the Province of BC has $625M for seven soccer games in Vancouver, and the City of Victoria is willing to allocate $10M for more police downtown, there is money to turn 28 Bastion Square into an open and accessible public building again.

But there’s still no vision.

28 Bastion Square could be an ideal site to investigate and promote the city’s history. There is no museum for the City of Victoria, and although the city has many historic sites and two museums with a provincial mandate (Royal BC Museum and the Maritime Museum of BC), only one museum is focused on civic history, the Victoria Chinatown Museum.

The City of Victoria currently provides no support to public history or museums. The heritage support it does provide is through the heritage house grant program which gives matching grants for conservation and repair to the private owners of heritage designated homes ($264k was doled out in 2023). This narrow support stands in stark contrast to council’s efforts to support performing arts and the music scene; in 2024 they went so far as to purchase a jazz club!

The Old Court House is an ideal location to engage the public with the complex and problematic history of the law and colonization in BC. In addition, the building could act as a hub for history, heritage, and arts related organizations in the city.

Restoring and reopening the building could activate Bastion Square to the benefit of local people, businesses, and the visitor economy.

Just as legal cases were once brought before the court, the evidence of Victoria's history could be brought before visitors for interpretation and engagement.

The longer we ignore talking about our past, the closer we get to demolition by neglect.