The Athletic Girl Not Unfeminine

One month ago, a study commissioned by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) found that trans women do not have an across-the-board biological advantage in athletics. Specifically, it found that while trans women had on average higher grip strength than cis women, they are worse off when it comes to jump height and a few respiratory measures. This study struck me immediately as significant, as the IOC has a long and dirtied history with sex testing of trans athletes. It is certainly meaningful for a study under their belt to push against the narrative that there is something unfair about trans (specifically trans feminine) participation in sports.

However, if it were not the IOC, I wouldn’t really care. To be honest, I still don’t care as much as I could. While I can see how this study might be useful as we approach another Olympics and people resume debating whether trans athletes are competing unfairly again, deep down I know that it won’t be enough. This is because I don’t believe that fairness, per se, is actually what the debate is about. To understand why, and what I think it’s really about, a journey through the history of sex testing (and women’s sports in general) may be necessary.

Sex testing—which has also been termed sex control, femininity testing, and gender verification, among other names—has been a part of professional women’s sports from almost the beginning. I say women’s sports, rather than just sports, to make it eminently clear that sex testing has never been a feature of men’s sports, owing to the fact that, because of cultural associations between masculinity and athleticism, there is no amount of athletic success men can attain that leads people to call their achievements into question.

Traditional histories of sex testing locate its emergence during the Cold War, claiming that the intense and politicized competition between nations characteristic of this period is what caused nations to raise skeptical eyes at the masculinity or femininity of their opponents, and to accuse them of cheating if they appeared “too” masculine. While they are correct in their characterization of the era, in recent years historians have begun to point out that sex testing long predated the Cold War and likely had more to do in those early years with fears that athletics were harmful to women. This is the period I wish to depart from.

Exercise for Interwar Women

Beginning in the 1930s, reports hit the American press about a series of European track and field athletes, born female, who had operations to become male. The fact that they were all track athletes confirmed people’s suspicions that track and field was particularly unfeminine, and that the sport could even be “masculinizing” women. Because track and field was the most popular and celebrated Olympic sport in the interwar period, for a woman to excel at it seemed hard to imagine. Additionally, the women who did compete in track and field were more often than not women of color or working-class women, in turn keeping middle and upper-class white (read: normatively feminine) women off the track and lending the sport a masculine image. Furthermore, according to sport historian Jennifer Hargreaves, “Because of the intrinsically vigorous nature of running, jumping and throwing events, female athletes were particularly vulnerable to reactionary medical arguments.”

The idea that sports could be harmful to women was not a new one, and these beliefs had been circulating since at least the turn of the century, as hinted by a 1902 article in the magazine Outing titled “The Athletic Girl Not Unfeminine,” which reads, “Like every one else, I have long been familiar with the stock arguments against athletics. One of those most frequently urged is that there is a risk of women injuring their health by such exercise.” The persistence of these beliefs is evident from interwar print materials. A later article in the January 1937 issue of Physical Culture told the story of tennis player Alice Marble, but not without a long section detailing the physical deterioration she suffered from her training.

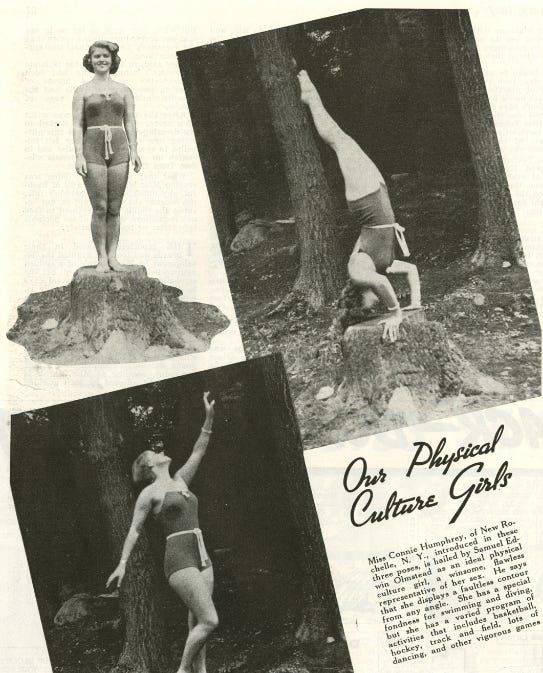

When, in that same issue, women were encouraged to exercise, the advice came in the form of a set of relaxation exercises for high-strung business girls. The author speaks of a type of office girl, apparently ubiquitous, who “[flies] into a rage at the helpless office boy, then [kisses] him when he cries.” These women, in her view, could learn to relax if only they exercised properly. A different article from the same edition titled “Our Physical Culture Girls” celebrates Miss Connie Humphrey, a female swimmer and diver who had competed in other sports, including track and field. Humphrey, portrayed standing upright, on her head, and in a yoga pose, is honored as “a winsome, flawless representative of her sex. . . . [S]he displays a faultless contour from any angle.” While she is hailed for her “vigorous” athleticism, the photos taken of her portray her as normatively feminine. What these examples suggest is that, in this period, women could be tolerated or even celebrated in the realm of physical culture so long as they did not appear mannish, bother the men around them, or encroach too heavily on their spheres of influence.

With all this in mind, it is no surprise that reports of female-born track athletes transitioning to become men would further unsettle sports officials and readers of the popular press about the supposed dangers of female athletics. Avery Brundage, future president of the IOC and chaperone of the American athletes at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, said in Germany that he was “fed up to the ears with women as track and field competitors. . . . [Their] charms sink to less than zero. . . . [And] they are ineffective and unpleasing on the track.” His frustration only increased following newspaper reports describing the sex-reassignment surgery of two former (female) European champions, Mark Weston and Zdenek Koubek. Historians have offered various interpretations of these athletes’ transitions, but as there is no scholarly consensus on the matter, I contend that it is important to trace the shifting cultural meanings attached to these athletes and their operations, both in the popular press of the interwar period and in the contemporary historiography of sex testing.

Mark Weston was a British athlete with a successful six-year career. In 1925, Weston earned the British Women’s Amateur Athletic Association (WAAA) shot-put title, and four years later he won first place in the discus, javelin, and shot-put events at the WAAA Championships. Despite celebration of his achievements, questions began to surface about their validity. Whether as a result of this public questioning or his own self-scrutiny, Weston began to have doubts as well. In May 1936, an article was published in the Pennsylvania newspaper Reading Eagle titled “Girl Who Became Man Tells of Metamorphosis.” In said article, Weston is quoted as saying “I always imagined I was competing as a girl until 1928. Then, competing at the world championships in Prague, Czechoslovakia, I began to realize that I was not normal and had no right to compete as a woman.” While the meaning of this statement on its own is unclear, Weston was given more time to speak in August of that same year. “In spite of the fact,” he said, “that I was reared as a girl and knew myself as a girl, my life was not girlish. Many girls are called tom boys, and I was really a tomboy when I was in school.” In this article in the Florence, AL Times Daily, Weston is given more room to explain his history, and he recounts stories of training in cricket and football with his male classmates, working at a clothing factory and realizing he had “no special aptitude for needlework,” and never “caring for powder, rouge, or lipstick.” Weston makes a clear appeal to the standard trans narrative of always feeling like he was different from a young age. So then, was Weston a trans man?

Doing Justice to Someone

According to transgender sports scientist and athlete Joanna Harper, Weston was likely intersex. “Weston had atypical genitalia and was advised to have surgery,” she writes in her 2020 book Sporting Gender. Harper argues that “there were several prominent female athletes in the 1930s who were probably hermaphrodites, or intersex as we would say today.” She supports this claim by noting that the frequent inbreeding in Europe and North America in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries could have been a cause of these athletes’ intersex conditions. However, the source she gives for Weston’s “atypical genitalia” is the article in Reading Eagle that I discussed above, which is rather unclear on the matter. It states that Weston’s sex change was performed over two operations by Dr. L. R. Broster and Charing Cross Hospital in London. It also states that Weston was in possession of a certificate from Broster which read, “Mr. Mark Weston, who was always brought up as a female, is male and should continue life as such.” While Harper reads this as a confirmation of Weston’s intersex status, I am not so convinced. For one, the early twentieth century saw a proliferation of biological and psychological theories of transsexuality, and so transsexuality, like “hermaphroditism,” could supposedly be read on the body (or the mind). When Broster says that Weston is male, he may not necessarily be declaring that he had atypical genitalia, but that there was something about his embodied sense of self that was male.

Women’s historian Joanne Meyerowitz argues in How Sex Changed that “sex change” originated as a European phenomenon and was not initially well-understood in the United States. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a theory of universal human bisexuality emerged in Europe. Contrary to our contemporary understanding of bisexuality as sexual orientation, some European sexologists used the term to claim that there was no such thing as a “pure” male or female, and that everyone possesses characteristics of either sex. This claim was bolstered by the discovery of the sex hormones, as it became known that men possessed trace amounts of “female” hormones and women possessed some amount of “male” hormones. Soon, Austrian physiologist Eugen Steinach would begin sex organ transplantation experiments on rats, and his work was taken up in humans by his associate, Robert Lichtenstern. While Lichtenstern’s experiments mostly attempted to “fix” unhealthy or “abnormal” men, his research was then taken up by Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science, where scientists first attempted “to transform a man into a woman or a woman into a man.” The institute officially published its experiments in the early 1930s, and rumors of sex changes began trickling into the American popular press, alongside a few references in medical textbooks and newspaper articles to the European theory of bisexuality.

It is clear that this theory of bisexuality had reached America by 1936, when an article titled “Change of Sex” was published in TIME. In discussing Weston’s transition, the article swiftly transitions into an elaboration of the concept, stating that “To sober medical men, it does not seem strange that Nature some times blurs sexual development in men & women. Biologists say there is no such thing as absolute sex.” One year later, a similar article was published in Physical Culture with the title “Can Sex in Humans Be Changed?” Once again, a discussion of Mark Weston’s transition becomes a discussion of his embodied bisexuality: “When I speak of a person’s sex,” the author writes, “I refer to his or her preponderant sex. Sex is relative. No man is 100 per cent male, no woman 100 per cent female.” The author later reveals himself to be a friend of “the late Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld,” evidencing one of the possible routes by which the theory of bisexuality made it to America.

Importantly, while the theory of bisexuality was evidently understood by the American press to some extent, Meyerowitz argues that sex change, particularly as it relates to transsexuality, was not understood upon arrival to the United States. According to Meyerowitz, the articles

addressed “sex change” accomplished through surgery but failed to specify what the operations entailed. They depicted sex-change surgery as unveiling a true but hidden physiological sex and thus tied the change to a biological mooring that seemingly justified surgical intervention.

In other words, American misunderstandings of an initially European science resulted in transsexual surgeries being reported in the American popular press as if they were merely “corrective” surgeries on intersex patients. This is clear from the aforementioned Physical Culture article, in which the author shows a clear lack of understanding of transsexuality, claiming that “It is possible to correct certain errors of nature, but it is impossible, with the present limits of medical science, to change the sex of a mature, normally developed human being.” It is for this reason that I caution against taking the American press at its word in its discussion of sex changes. Furthermore, Judith Butler, in her discussion of the controversial mid-century experiments performed on intersex patients, writes that “it seems to me that I must be careful in presenting [the patients’] words.” She continues:

since I do not know this person and have no access to this person, I am left to be a reader of a selected number of words, words that I did not fully select, ones that were selected for me, recorded from interviews and then chosen by those who decided to write their articles on this person. . . . So we might say that I have been given fragments of the person, linguistic fragments of something called a person, and what might it mean to do justice to someone under these circumstances? Can we?

But failing to do justice to someone is not the sole danger of reading these stories at face value. Medical historian Vanessa Heggie argues that “If we selectively remember only rumours [of intersex athletes] that were ‘revealed to be right’, suspicion would appear a disproportionately powerful predictor of gender ambiguity.” Continuing with this logic, I argue that if we take the American press at its word when it depicts successful female-born athletes as having a natural advantage owing to an intersex condition, then we may find ourselves confirming people’s suspicions that female athletes cannot excel unless they are not totally female. In attempting to discern whether or not athletes like Weston were “really” intersex or transsexual—which contains the hidden question of whether or not they should have been allowed to compete—we are merely contributing to the racialized medical and patriarchal surveillance and policing of their bodies. Under these circumstances it is neither possible nor responsible to attempt to read the details of these bodies and their alleged “advantages” through the historical record, and it is more historically and politically useful to instead look at the cultural meanings that became attached to these sex changes.

The Meaning of Transition

The Times Daily describes Weston’s physical appearance as “about medium height with the square shoulders of an athlete and hands that are masculine rather than feminine.” While some of the article makes a spectacle of Weston’s life, this section interestingly seeks to naturalize rather than exoticize his masculinity. The article continues: “He has a man’s grip when he shakes your hand, and his figure is masculine. He has pleasant features, with coal black hair and an olive complexion. He would best be described as a good looking man of 30 with little trace of femininity in his looks or carriage.” In light of this appraisal of Weston’s seemingly natural masculinity, the comment about his “square shoulders of an athlete” can be read as a way of stabilizing the sex binary in light of female athleticism. While anxieties about gender roles abounded as women began to encroach on men’s spheres of influence—politics, the marketplace, and now sports—Weston’s transition into normative masculinity allowed for a stabilization of these gender roles by confirming that sports, track and field in particular, were a masculine enterprise. On top of being used to prove that athletics could masculinize women, which was used as a reason to police female athletes’ gender through sex testing or even abolish female athletics altogether, Weston’s story was read in the press to prove that, because athletic women were becoming men, there must be an inherently masculine component to sport, providing a justification for female exclusion under the “separate spheres” ideology of the era.

These calls to implement sex testing would be answered after the war. While international sporting events were canceled en masse during the second World War, in 1946 the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) introduced rules mandating that female athletes should receive a certificate from a physician verifying their sex prior to participating in the European Athletics Championships in Oslo. This meant that, until the introduction of a new rule some two decades later, womanhood in sports was determined by individual physicians’ own interpretations of sex. This lack of standardization further complicates the possibility of taking the press at its word in its reporting of “ambiguous” female athletes.

The first victim of this new rule was Leon Caurla, a French female-born runner who in 1946 earned bronze in the 200-meter race and silver in the 4 x 100-meter relay. For reasons that remain unclear, when asked to undergo a mandatory sex examination, Caurla refused, which led to his expulsion from competition by the French Athletics Federation. Caurla’s story provides another useful window as to why intersex narratives may have been favored over transsexual narratives when discussing female-born athletes.

In 1952, Caurla’s transition was publicly reported by the Sydney Morning Herald. His transformation supposedly “happened over a period of years until in 1948, he learned that he was in fact a man. . . . Ultimately, he had an operation that made the change of sex final.” While not appearing in an American paper (though also not in a European paper), the article still uses language that minimizes Caurla’s potential agency. A similar trend can be seen in the 1966 article in LIFE titled “Are Girl Athletes Really Girls?” which reads: “Soon afterward [he] changed [his] name to Leon when doctors decided [he] was really a man.” An image caption on that same page reads “Burley [Leon] Caurla was one of Europe’s top ‘women’ sprinters before surgeons made [him] a man.” This lack of agency attributed to Caurla—”learned that he was in fact a man,” “doctors decided [he] was really a man”—combined with the curious use of quotations around the word “women,” suggests that Caurla’s transition was being read through an intersex, rather than a trans, framework. While this framing would appear to be a product of ignorance had it occurred three decades earlier, the decision to frame his sex change in this way in an era when the American public was rather more familiar with transsexuality (Harry Benjamin would publish The Transsexual Phenomenon, his treatise on the subject, in that same year) seems more intentional.

Clues as to why Caurla’s story was framed in this way can be found within the article’s broader context. It was published shortly following the 1966 European track and field championships in Budapest, in which “234 female contestants . . . had to take part in an extraordinary private parade—in the nude before the inquisitive stares of three women gynecologists.” This rule had been adopted by the IAAF in response to “persistent speculation through the years about women who turn in manly performances—and some notable scandals as well.” The athlete primarily cited in the article as delivering a particularly “manly” performance in recent memory was none other than Leon Caurla. It seems to me that if Caurla’s transition was intended to provide a justification, according to LIFE, for intensifying the surveillance and policing of female bodies in sport, it was necessary that Caurla be depicted as intersex, rather than transsexual, even though there was little evidence for this point. This is because if Caurla were “merely” transsexual, he would have been a normal woman before transitioning, meaning that his athletic achievements would have been possible even with a “normal” female body. As we have seen, this conclusion was the source of significant public worry, and so it may have been necessary to portray Caurla, and other trans female-to-male athletes, as intersex, such that their achievements could be attributed to a degree of maleness and therefore naturalized.

As stories of female-born athletes becoming men hit the press, earlier fears that athletics were harmful to women began to take a new shape, morphing into fears that women were being masculinized by sports. In addition, these stories, when framed in specific ways, lent credence to the deeply-ingrained belief that sports were a masculine enterprise. In the early years of the Cold War, fears of cheating sparked by intense competition between nations mean that these masculinization anxieties gave way to the today more familiar tropes of “male impostors.” A 1966 article in the Sarasota Herald Tribune read that “If the Commies hadn’t been guilty of substituting men for women in the first place, the new rule of the IAAF wouldn’t have been necessary.”

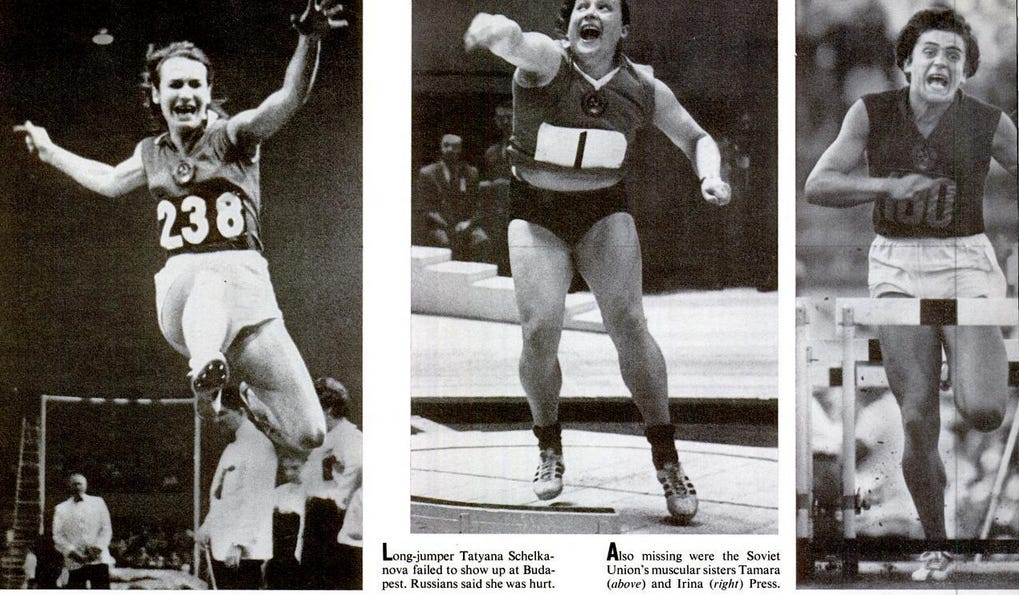

Unsurprisingly, racialized notions of gender were at play in the specific accusations of male substitution. The aforementioned LIFE article names four women from the Soviet Bloc who were deemed particularly suspicious. The first is Romanian high-jumper Iolanda Balas, who, the article reads, “sat out the games with square-jawed determination.” The second is Russian long-jumper Tatyana Schelkanova, whose team said she was injured. The third and fourth athletes are “the Soviet Union’s muscular sisters” Tamara and Irina Press. They attracted suspicion for two reasons. for one, none of the four women attended the Budapest games, and secondly, because they are Eastern European, they are charged with not meeting Western standards of femininity. These factors combined led people to believe that these women were skipping the games because they knew the new IAAF rule would out them as not “Really Girls.” In this instance, it is not just that these women are athletic that causes the public discomfort, it is that their departure from whiteness is read as excess masculinity, further compromising their case for inclusion in women’s sports.

Beyond Fairness

Fairness, then, is a red herring. As is evident from the history of sex testing, which could perhaps be termed “sex skepticism,” or even “sex anxiety,” when people talk about fairness in women’s sports, what they are really talking about is their fear of athletic, nonwhite, or otherwise nonnormative women. We should be careful, then, about trying to beat them on the “fairness” angle. When we link the IOC study at conservatives on Twitter, for example, are we not just saying: Don’t worry! These women still aren’t as strong as men! You may relax now and return to a world where women are simply, obviously, and inherently the weaker sex!

Weirdly enough, the study itself gives us an alternative way to proceed. The authors caution against blanket bans on trans athletes and urge sport-specific research, a move which is similar to a recent piece by sports sociologist Roslyn Kerr in The Conversation which advocates for a move away from gendered categories in sports altogether. Kerr advocates a Paralympic model, as Paralympic sports, due to the incredibly diverse nature of disability, have already had to pay much closer attention to the issue of classification. “In the 1990s,” Kerr writes, “the classification system changed to one that was based on functional ability rather than on medical conditions.” What this means is that, rather than an identity or diagnosis-based classification system, athletes are classified by the finer details of their bodies—“the movements their body can perform,” in the Paralympic case.

How might this play out in nondisabled athletics? Take track as an example. Rather than dividing the 100 meter dash into male and female categories—which presumes that women are inherently weaker than men and sneaks in an upper limit on what can be considered natural female athleticism—it could be divided into two or more groups of athletes based on their muscle mass and quantity of fast-twitch muscle fibers. As I have explained in more detail in a previous article, sex categories such as “male” and “female” are merely generalized proxies for more specific information about the body, meaning that when we ask if someone is “male” in a sporting context, we can cut out the middleman and instead inquire into their muscle mass, grip strength, density of particular muscle fibers, et cetera. While arguably still invasive, these questions are more precise and less politicized than asking someone (or attempting in futility to scientifically determine) their gender.

Historically, the “male” and “female” sports divisions have existed as proxies for “stronger” and “weaker,” and the existence of such categories has upheld a gender binary and served as a rationale for the policing and surveillance of athletic bodies: a process that harms women, trans people, intersex people, people of color, and poor people, to name a few. In a world where such proxies exist, we have a lot to gain by getting rid of them entirely and being more precise about what’s going on.