HRT: A Transfem's Guide

Last March, I was sitting at a cramped desk in my college library when I received an email that I had a new message in my patient portal. Having just undergone lab work, four months on a meager dose of estradiol and spironolactone, I was eager to see what we had uncovered.

My nutrient profile, to my surprise, was completely within normal range. Satisfied, I kept scrolling, until I eventually found the data from the estradiol and testosterone assays. Dread soon crept over me. My estradiol, though technically out of the male range, seemed rather low. A quick google search revealed that my levels were on the lower end of those expected during the follicular phase—the part of the menstrual cycle comprising the period and the week preceding ovulation.

Thanks for reading Leah Long! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Feeling a pit in my stomach, I glanced at my testosterone level, which to my dismay was still comfortably within the male range, and nearly ten times what it should be for adult women. My dissatisfaction with my transition—as well as the strange PMS-like symptoms I’d been experiencing in the middle of the night—became clear to me. I started feeling uneasy about just how little I knew about what I was doing.

I like my doctor. After one appointment I had easy access to hormones. I feel listened to. I never feel like anything is being imposed on me. We make our decisions together. But many—and dare I say most—trans people do not have what I have. And still, even with little standing between myself and medicine, I spent the first four months of hormone therapy not knowing that a few simple changes could have freed me from the malaise I was experiencing. And so in service of myself and others, I started to read. If this medical knowledge were to be so central to my life, I wanted it for myself.

As you read this I hope you remember at every turn: I am not a doctor. I am not a licensed medical professional in any sense of the word. In fact, I am not a professional of any kind. So why am I writing? For one, I get asked a lot of questions about hormones by other trans people, and I felt I ought to put them all in one place. Secondly, I want to help democratize this medical knowledge that is central to the lives of all trans people who are medically transitioning. Thirdly, I’ve seen a lot of trans people get stuck in very bad situations for a very long time due to an inequality of information and authority between themselves and their doctor. And lastly, I’m writing because I worry that in a few years time, with the passage of various legislation, the knowledge of how to “DIY” your medical transition will become vital. Ultimately, my goal is to give trans women a resource that gives them more power and agency in medical contexts, not only because I worry that this agency is being stripped away, but also because for some it was never there in the first place.

In what follows I’ll go over what hormones do, how they work in the brain, what constitutes “success” during hormone therapy, what your options are, and some various health concerns such as bone health, fertility, and cancer. Unfortunately, this information will be specific to feminizing hormone therapy, as I find that this research is best communicated by someone with a personal stake in the matter. While I would love to also write about hormone therapy for transmascs, I’m less able to anticipate common concerns than I am when talking about my own experience. Still, I believe that parts of this essay will be valuable to those who are not transfeminine, and perhaps even to people who do not consider themselves trans at all.

Without further ado, let’s begin.

The Big Three

Estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. These are the three hormones central to the transfem’s experience. Despite some popular misconceptions, each of these hormones are present in all bodies, only in varying proportions. Yes, cis women have testosterone, and no, progesterone is not only “the pregnancy hormone.”

Adult cis men, for example, have testosterone levels roughly between 350 and 1200 ng/dL, estrogen levels between 8 and 35 pg/mL, and progesterone levels below 0.1 ng/mL. When I mentioned earlier that my testosterone was comfortably within male range, this was the range I was referring to.1

Because of menopause and the menstrual cycle, the picture is more complicated for adult cis women. During the follicular phase, or the first half of the cycle, estrogen levels are typically between 30 and 100 pg/mL. This then spikes to around 1000 pg/mL during ovulation, before dropping to between 70 and 300 pg/mL in the luteal phase, or the latter half of the cycle. Progesterone follows a less complicated trajectory, with typical levels of 0.1 to 1.5 ng/mL in the follicular phase and 15 to 25 ng/mL in the luteal phase.

Before menopause, cis women commonly have testosterone levels between 10 to 55 ng/dL. After menopause, this drops to between 7 and 40 ng/dL, while estradiol levels typically plunge to below 15 pg/mL and progesterone levels below 0.1 ng/mL.

All of this raises the question: as a trans woman, what levels should I aim for? I want to answer this question in a few different ways.

Many doctors, as well as the Endocrine Society, recommend that trans women keep their levels between 100 and 200 pg/mL, comfortably in the luteal range for cis women. While at first glance this seems relatively straightforward, it is important to note that trans women are not cis women, and so things are slightly more complicated.

While elevated estrogen levels are important for transfeminine hormone therapy, the first priority is suppression of testosterone levels2. This can be done in a couple different ways. The first is through use of anti-androgens (commonly spironolactone), which prevent androgens (i.e. testosterone) from binding to androgen receptors, reducing their effects on the body.

The second method is simple in practice but slightly more complicated to explain. In short, whenever you administer external (sometimes called exogenous) hormones, your body learns to produce less of its own. The simple reason for this is that your brain doesn’t care what hormones it has, it only cares how much. The more complicated reason is that exogenous hormones have antigonadotropic effects, meaning they cause a decrease in the gonadotropins: luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). The gonadotropins signal to the gonads to produce whatever hormones the gonads are made to produce. This is why, in the above diagram, LH and FSH follow a similar trajectory to estrogen and progesterone in cis women.

In short, when a trans woman takes estradiol or progesterone, the body compensates by producing less testosterone. So it is possible, with high enough estrogen and progesterone levels, to suppress your testosterone into the range that is typical for adult cis women, even without using a testosterone blocker like spiro. This often means keeping estradiol levels above 300 pg/mL, though I have seen full testosterone suppression with lower levels of estradiol and progesterone. Some doctors will caution you against higher estradiol levels for various reasons I will discuss later, but this is mostly a misnomer.

But all this talk about numbers misses a more fundamental point: if you are happy, it doesn’t matter. In the first few months of my transition, it didn’t matter that my numbers were out of place, it mattered that I wasn’t happy. My numbers were merely an explanation for my dissatisfaction. All bodies have different responses to hormones, and no two trans people want the same body. While I do think it is important to check your levels every once in a while, I strongly advise against chasing certain numbers. I’ve seen trans women who feel completely satisfied with their transitions at far lower than even the Endocrine Society’s 100-200 pg/mL range. It’s much better to start by asking yourself how you feel.

A Note on Progesterone

You may have noticed that I have said very little about progesterone so far. This is because we know almost nothing. Progesterone’s workings in trans women’s bodies have scarcely been studied aside from a single study in 1989. For a more candid description of what one Twitter user calls “the progesterone wars,” you can see this thread. For the purposes of this article however, it is just important to know that for one reason or another, doctors will not study what progesterone does in trans women.

However, the author of that 1989 study published a paper a few years ago3 which gives six discrete reasons that progesterone is likely to be beneficial for trans women, based on past clinical experience and a review of the literature on progesterone in general. These reasons are as follows:

Progesterone reduces the conversion of testosterone into dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the hormone that masculinizes skin and hair follicles.

Progesterone slows the pulse rate of LH and lowers average LH levels, which leads to a decrease in gonadal testosterone production.

Progesterone is thought to be necessary for breast maturation and areola enlargement.

Progesterone promotes bone formation and can increase bone mass density.

Progesterone significantly improves deep sleep, decreases the time it takes to fall asleep, and decreases midsleep wakening.

Progesterone can lead to improved cardiovascular health and prevent against heart attacks.

In my own experience, progesterone has caused my skin to clear up significantly, improved my breast development, and drastically improved my sleep. Others have reported positive mood changes, increased anxiety, and heightened libido. The science is still uncertain, but if you are having a bad experience with progesterone it may help to try a different dosage or route of administration.

Routes of Administration

Estrogen and progesterone can be administered in various ways. The way you take these hormones determines how they will affect your levels, how long they will stay in your system, and how often you need to take them, among other things. In my view, the four most important routes for estrogen are the oral, sublingual, subcutaneous, and intramuscular routes.4

The oral route involves simply swallowing a pill. This causes estradiol levels to rise rapidly for 1-3 hours followed by a rapid decline, though levels remain elevated for up to twelve hours and decrease slowly during the following time.

The sublingual route is similar to the oral route, but it involves letting a pill dissolve under your tongue, rather than swallowing it. Many estradiol tablets made for oral use can also be taken sublingually. With the sublingual route, concentration rises rapidly for about one hour where it then rapidly falls, slowly diminishing thereafter.

The subcutaneous route involves the surgical implantation of crystalline slow-release estradiol pellets. With this route, estrogen is released at a slow, even rate. Subcutaneous administration is associated with relatively small fluctuations in levels in the 6 months after implantation.

The last route I will discuss is the intramuscular route, which involves injection of estradiol esters. When people speak of “injections,” this is the route they are referring to. With the intramuscular route, estrogen is released at a slow rate, peaking around 2 days and slowly diminishing for around 10 days after.

Now that I’ve thrown all this information at you, let’s figure out what to do with it. Weekly estradiol injections are often seen as the gold standard for transfeminine hormone therapy, as they are less invasive than the subcutaneous route, as well as being less frequent and more effective than the oral and sublingual routes. However, not everyone (myself included) can access injections, and many people have trouble with needles.

If injections are out of the picture for you and subcutaneous isn’t your thing, you are left with either the oral or sublingual routes. The oral route is the easiest, but it comes with certain health risks that are not always discussed. When you swallow a pill, it makes its first pass through the liver, where it is only then metabolized. This process reduces the bioavailability (how much estrogen you get) and increases liver strain, which can be a problem for long-term use. The first pass effect also increases the risk of blood clots and thrombosis. It is for these reasons that I prefer the sublingual route. Dissolving a pill under your tongue means it bypasses the liver and directly enters the systemic circulation, which results not only in significantly reduced liver strain, but in significantly higher levels of estrogen.

![Estradiol levels over a 24-hour period following a single 0.25, 0.5, or 1 mg dose of sublingual estradiol or a single 0.5 or 1 mg dose of oral estradiol in postmenopausal women.[1] Source: Price et al. (1997).[1]](https://assets.buttondown.email/6e5d2270-1b46-4894-a9f4-11b025732c19_300x274.png)

I choose to take my estradiol sublingually as it is my closest option to injections at the moment. I dissolve one 2mg pill in the morning and another at night, as the “spikiness” of the sublingual route means it is advised to evenly space your dose 2-4 times throughout the day. This is a much lengthier process than the oral route, but in my experience, it’s been worth it. I noticed that the moment I started dissolving my pills rather than swallowing them, my skin cleared up and my libido largely went away. There’s an added comfort in knowing that I am sparing my liver some strain and reducing my chances of blood clots and other cardiovascular problems.

Now let’s talk about progesterone. I’ll discuss three routes: oral, intramuscular, and rectal. With the oral route, concentration rises rapidly and peaks after 1-2 hours, declining rapidly to baseline levels within 4-6 hours. With the intramuscular route, concentration rapidly rises after 8 hours and then rapidly declines after 48 hours. Lastly, there is the rectal route, which involves placing a pill in your rectum and waiting for it to dissolve. With the rectal route, concentration rapidly rises and peaks after 6 hours, remaining at this level for 24 hours and remaining above baseline levels after 48 hours.

The playing field is a bit different here. Injections are no longer as sought after, as they have to be readministered every three or so days. The oral route is not perfect either as it results in relatively low bioavailability. Additionally, orally administered progesterone metabolizes into a few dozen other metabolites, some of which act as sedatives. Most people prefer the rectal route, as it avoids this drunkenness and allows for greater bioavailability. Personally, I take my progesterone orally as I do not mind the drunkenness and I’ve been satisfied with my changes so far, but I have nothing against the rectal route.

Ultimately, my recommendation is weekly estradiol injections with nightly rectal progesterone. An anti-androgen is not usually needed with this kind of regimen, as injections keep estrogen levels high enough that further testosterone suppression is not usually needed, especially when you factor in progesterone.

Anti-Androgens

The five main anti-androgens are spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, bicalutamide, finasteride, and GnRH agonists. Unlike estrogen, anti-androgens are less of a sure science and there are downsides to each, meaning that there is no “gold standard” and treatment is more individualized. Another reason I recommend injections at high enough doses to fully suppress testosterone is to avoid having to deal with anti-androgens. However, if for whatever reason you don’t have access to injections, it may be useful to know the pros and cons to each anti-androgen.

Spironolactone

Spironolactone is by far the most commonly prescribed anti-androgen in the United States, and it has been used in trans medicine as early as the 1980s. However, its effectiveness as a testosterone blocker for transfems is unclear. This is because while some anti-androgens reduce the total amount of testosterone in the blood, spiro largely leaves the amount of testosterone unchanged but prevents it from being used by the body. What this means is that with people taking spiro, blood tests are ineffective at determining how much testosterone is actually being used in the body, and so we have to resort to more qualitative markers such as facial and body hair growth. Animal studies looking at such markers seem to suggest that the actual effectiveness of spironolactone at promoting feminization is significantly lower than other anti-androgens, such as cyproterone acetate, but it is obviously difficult to generalize these findings to humans. In 2018, Aly at Transfem Science reviewed the existing data on spironolactone and found that, while spiro may be effective at preventing acne and facial hair growth in cis women, it is likely far less effective at promoting feminization in trans women. Recall that cis women have far lower natural testosterone levels than trans women, and so spironolactone does not have to do as much work to suppress cis women’s testosterone levels.

While there are a variety of safety concerns about spiro, none of them are too severe. Spiro is a diuretic, meaning it can dehydrate you and make you have to pee more, but these effects vary from person to person. I notice some adverse side effects on 100 mg daily, but I am mostly fine. I know one trans woman who had to go from 100 mg to 50 mg after frequently losing her balance and nearly blacking out, and I know another trans woman who is completely unaffected by 300 mg daily. The most severe side effect of spironolactone is the risk of elevated potassium levels (hyperkalemia), but a recent study found that this risk was very low in people under 45 years old. The study authors recommend frequent potassium monitoring only for those older than 45 or those with other conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, renal disease, or heart failure. Other than these risks, spiro appears to be safe for long-term use.

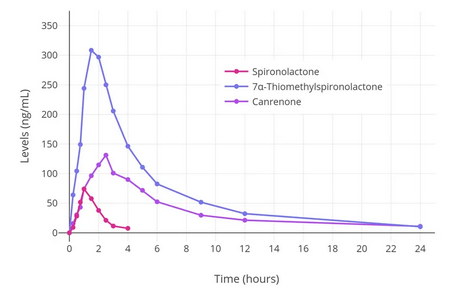

If you decide on using spironolactone, it may be beneficial to split the dose in half and take it twice a day, as it reaches peak effectiveness within the first two or three hours (as shown in the above chart) and then rapidly decreases.

Cyproterone Acetate

While cyproterone acetate is likely a more effective anti-androgen than spironolactone and has also been used in trans medicine since the 1980s, it is not licensed for use in the United States. That said, for transfems in other parts of the world, it may be a better option than spiro. Cypro promotes feminization in two ways: first, it is similar to spiro in that it blocks existing testosterone from being used by the body, but secondly, it is also a progestogen, meaning it tells the body to produce less testosterone, as discussed above. When taken with estrogen, cyproterone acetate has been shown to fully suppress testosterone levels in trans women.

However, there are a number of safety concerns with cyproterone acetate. For one, liver damage has been reported in patients treated with cypro, but this has only occurred at doses of at least 100 mg daily. Cypro use in trans women has also been associated with a four times higher incidence rate of meningiomas (tumors that form near the brain and spinal cord) than cis women, likely due to the presence of progesterone receptors in meningiomas. Both of these complications are associated with higher doses of cypro, and so research has been done to determine the lowest possible effective dose of cyproterone acetate.

A 2021 study found that doses of cypro as low as 10 mg are just as effective as higher doses, with fewer associated health risks. While future research remains to be done on whether doses lower than 10 mg are still effective at suppressing testosterone, if you choose to use cyproterone acetate, I wouldn’t recommend any higher than 10 mg. Additionally, because cyproterone acetate is a progestogen, it is not necessary to take progesterone when on cypro.

Bicalutamide

Bicalutamide is an anti-androgen typically used to treat prostate cancer, and it has only recently been considered for use with trans women. While bicalutamide is not recommended by the current standards of care, there has been increasingly more discussion about its use over the last few years, and so it warrants a discussion.

Bicalutamide works similarly to spironolactone and cyproterone acetate in that it prevents testosterone from being used by the body, but it is significantly stronger than the former medications. In fact, bicalutamide can even cause the body to overcorrect and produce more testosterone, even if this testosterone isn’t being used, which means that just like with spiro, it is difficult to assess the effectiveness of bicalutamide by looking at the amount of testosterone in the blood. However, transfems taking bicalutamide have reported a reduction in acne and facial hair growth.

One notable effect of taking bicalutamide is the development of breasts even without taking estradiol. This likely happens for two reasons: firstly, bicalutamide reduces testosterone such that the ratio of estrogens to androgens causes the estrogens to take precedence, and secondly, by increasing the total testosterone in the body, some of that testosterone may be converted into estradiol through a process called aromatization.

The primary safety risk with bicalutamide is liver damage, which is a rare but well-known phenomenon. While there has only been one official case report of liver damage in a transfem taking bicalutamide, this is an important risk to consider. The majority of liver damage cases with bicalutamide occur within the first three to four months of treatment, and so the FDA recommends that liver function is tested at regular intervals during the first four months of use. While severe liver damage and failure has been reported in prostate cancer patients taking bicalutamide, the risks may be lower in healthy trans youth taking a lower dosage.

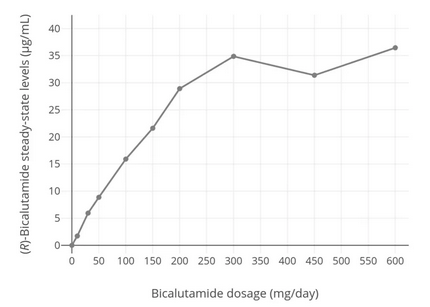

As shown by the above chart, bicalutamide levels increase steadily with dosage until about 300 mg, where they taper off. If you do choose to use bicalutamide, it may be wise to do so at a dose less than 300 mg.

Finasteride

Unlike the aforementioned anti-androgens, finasteride works by blocking the conversion of testosterone to the more potent dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which, as I mentioned above, is responsible for masculinizing skin and hair follicles.

While finasteride is sometimes used with transfems, it is unclear what benefit this has, especially considering that it has been shown to increase total testosterone levels. It makes more sense to focus on lowering testosterone itself so that less of it is available to be converted into DHT. As noted above, progesterone is also a DHT blocker. Additionally, a case report of a trans woman who saw a regrowth of scalp hair after six months of estradiol and spironolactone suggests that finasteride is not necessary to block DHT.

GnRH Agonists

The last group of anti-androgens worth discussing is GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) agonists, which are markedly different from the anti-androgens described above. Counterintuitively, GnRH agonists work by stimulating the receptors that tell the body to produce more hormones. While this leads to an initial rise in testosterone levels, the receptors soon become desensitized, and testosterone levels rapidly decline. For this reason, GnRH agonists have been referred to as a “readily reversible orchiectomy.”

Previously, these medications were rarely used due to their prohibitively high prices, but recently the GnRH agonist Buserelin has become inexpensively available for purchase as a nasal spray through online pharmacies. While I will not go into it here, information about dosing and how to obtain this medication can be found at Transfem Science. Buserelin has no known safety risks, which makes it a preferable alternative to the anti-androgens described above, with the main downside being that it can be difficult to access.

Health Concerns

I’d like to conclude with a brief overview of some general health considerations when undergoing feminizing hormone therapy.

Cardiovascular Risk

To start, I mentioned earlier that some doctors will advise against estrogen levels above 300 pg/mL, as they are worried about elevated cardiovascular risk at these levels. There is some truth to this, as both endogenous (produced by the gonads) and exogenous estrogen are known to have a procoagulatory (clotting) effect on the blood. However, 300 pg/mL is, strictly speaking, still quite low. Recall that ovulation in cis women can cause estrogen levels to spike to around 1000 pg/mL, and that estrogen levels during pregnancy are often well into the thousands. This is what I mean when I say that warnings about blood clots are mostly a misnomer, but I would still like to look at the data on blood clots in trans people.

A 2021 study5 found that blood clot incidence per 10,000 person-years was 42.8 for trans women, 34.8 for cis women, 11.1 for cis men, and 10.8 for trans men. This means that trans women have a class-wide higher incidence of blood clots compared to their cis counterparts, but this number is still not exceedingly high. Furthermore, when you break it down by route of administration, the oral route had a higher incidence (34.0) than non-oral routes (11.2), and when you break it down by type of estrogen, older estrogens such as ethinyl estradiol and conjugated equine estrogens (CEEs) had a higher incidence (293.1 and 49.0, respectively) than bioidentical estrogens (31.5), which are far more common in recent years. It is important to note that cigarette use is also quite common among trans women compared to cis women, and this is almost certainly a component of the higher incidence of cardiovascular troubles.

In short, the cardiovascular risk of non-oral bioidentical estrogen (especially with the cessation or prior lack of smoking) is likely still higher than that of cis men, but comparable to that of cis women.

Cancer Risk

While earlier studies indicated that breast cancer risk among trans women receiving hormone therapy was comparable with the risk in cis men, a recent, more thorough study showed a 46-fold increased risk of breast cancer in trans women compared with cis men, though this is still lower than the risk for cis women. However, when breast cancer does occur in trans women, it is often at a younger age than it is usually seen in cis women, and after a relatively short duration of HRT.

The risk of prostate cancer in trans women appears to be lower than in cis men, which may be due to lower levels of testosterone. However, many of the reported cases of prostate cancer in trans women had metastases at time of diagnoses. This could reflect a more aggressive form of prostate cancer in trans women, but it could also be a product of a delay in diagnosis due to improper screening techniques.6

A study published in 2020 by Sutherland et al. discusses and proposes ideas for medical care and cancer risk assessment of trans and nonbinary youth. They note that one’s experience of gender is prone to change over time, which makes it difficult to standardize when and how cancer risk assessment should be implemented. They say that cancer risk assessment and genetic testing may be medically necessary before 18 years of age if the patient meets certain criteria for consideration of risk, which is likely to inform decisions about hormone therapy.

They also discuss the fact that trans women may have longer exposure to estrogen and progesterone, as they are likely to take it at higher doses for proper suppression of gonadal function, and they are less likely to cease taking it at menopausal ages. Additionally, as trans people start to begin hormone therapy at younger ages, the data will begin to change.

Ultimately, the authors recommend organ-based routine cancer screening in accordance with the current general population guidelines.

Periods & Menstruation

Some transfems on estrogen attest to feeling period-like symptoms (such as sore breasts, mood swings, and irritability), but the existence of a period for transfems is far from an established fact. One trans neuroendocrinologist on Twitter has proposed that trans women’s periods could arise through the interactions between exogenous hormones and hormone signaling dynamics in the brain, but ultimately concedes that we don’t know, and that it’s okay that we don’t know.

However, while the transfem period has not been ruled out, it is important to recognize that someone without a uterus cannot menstruate. There is a distinction to be made between periods—that is, semi-regular hormone cycles and their effects—and menstruation.

For what it’s worth, I should mention that the only times I have felt recognizably PMS-like symptoms are when I was already on a bad regimen and missed a dose or two. It is always possible that period symptoms are due to a poor regimen rather than a regular cycle.

Other Concerns

A 2015 study7 found that trans women saw an increase in bone mass density after the first and second years of hormone therapy.

Infertility due to hormone therapy is likely, though not guaranteed, and fertility desire should ideally be addressed prior to the administration of hormones.8

Closing Remarks

I want this essay to become a living document. Please do not hesitate to reach out with questions or if you have objections to anything I have said here. As I learn more I will continue to update this essay, but as it stands now I think it serves as a handy overview of the basics. Any edits made to this essay following publication will be reflected down here.

I want to close by thanking the people behind Transfem Science, a website that I reference extremely often when researching transfeminine hormone therapy.

March 20, 2023: Added “Periods & Menstruation” section under “Health Concerns” heading.

These numbers come from Dennis Styne’s Laboratory Values for Pediatric Endocrinology

The following information and images are from Kuhl (2005) and were put together from data gathered on cis women receiving hormone replacement therapy