Go and get your rock

The first year of the pandemic had me thinking about time loop movies. The laziest google search tells me I wasn’t alone in this. Many of us, if we were lucky, spent most of our hours within our homes. The days had the tendency to run together and repeat themselves. Some people attempted to interrupt the monotony with zeal for sourdough starter or backyard workouts. When that lost its pizzazz, we gardened or watched 12-season TV shows.

Still others found fulfillment in local mutual aid projects - bringing food to community fridges, hosting aid distributions in parks for their neighbors, handing out water and masks at demonstrations for Black lives during the 2020 uprisings.

In the time loop films I’m thinking of, characters live the same day over and over again, in a deadening purgatory from which there is no escape hatch. Even suicide brings them right back to the start. They’re often haunted by past mistakes or traumas, or their own self-destructive tendencies. In desperately seeking an out, they remain stuck.

I find time loop movies to be rich texts exploring the evolution from cynical nihilism to a kind of hopeful absurdism. They can be read as metaphors for depression, addiction and recovery, especially Palm Springs. In these films, the main characters can’t “solve” the time loop before they integrate an important lesson into their consciousness.

In Groundhog Day, Bill Murray can’t move on to February 3rd until he accepts that he’s in February 2nd forever, so he may as well use his unique knowledge and skills in service of others.

In Palm Springs, Andy Samberg and Cristin Milioti can’t escape their time loop until they literally “blow up their life” by making a different choice than the ones they’ve made thousands of times.

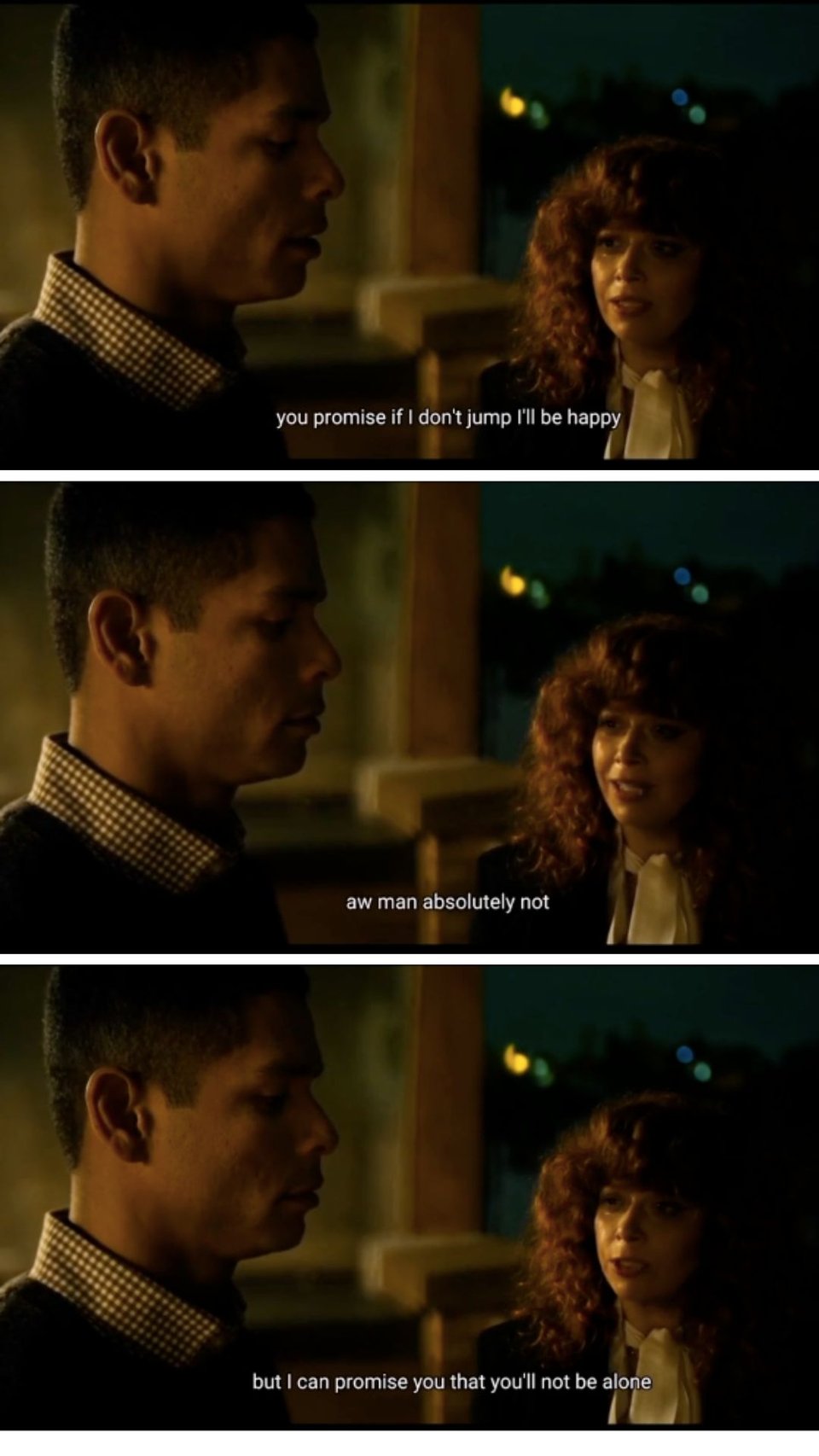

In Russian Doll, Natasha Lyonne dies over and over -by drowning, freezing, falling, car crash, gunshot, gas explosion - only to keep waking up at her 36th birthday party. She can’t escape this loop until she reaches out to Charlie Barnett, another character who is dying over and over, in the moment he’s about to jump off the roof of his apartment. Meanwhile, he can’t escape his own loop until he reaches out to her in the moment she’s about to make a destructive decision of her own. By interrupting each other’s self-annihilating choices, they free themselves from their purgatories.

Most of the main characters in these works start out with a bleak nihilism that devolves into hedonism and callousness. If every day is the same, if nothing they do matters, they may as well party hard and act like fucking assholes. Nobody’s going to remember this when the day starts all over again, right?

Their recovery begins when they realize the drugs aren’t working. They’re still trapped and miserable. If there’s another way out, they won’t find it in denial or avoidance.

If nihilism is the belief that there’s no real meaning to life and no universal values, and existentialism is the belief that we must create our own meaning in the face of a random and uncaring universe, then absurdism is the tension that arises when we search for meaning in a universe we know to be indifferent to us. It’s in that paradox that the characters in time loop movies achieve a level of emotional maturity and clarity that frees them from the monotony of their metaphorical loops.

The framework of absurdism comes from French philosopher Albert Camus, who described the concept this way: “This world in itself is not reasonable, that is all that can be said. But what is absurd is the confrontation of this irrational and the wild longing for clarity whose call echoes in the human heart.”

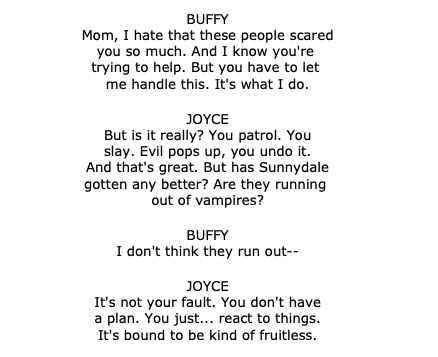

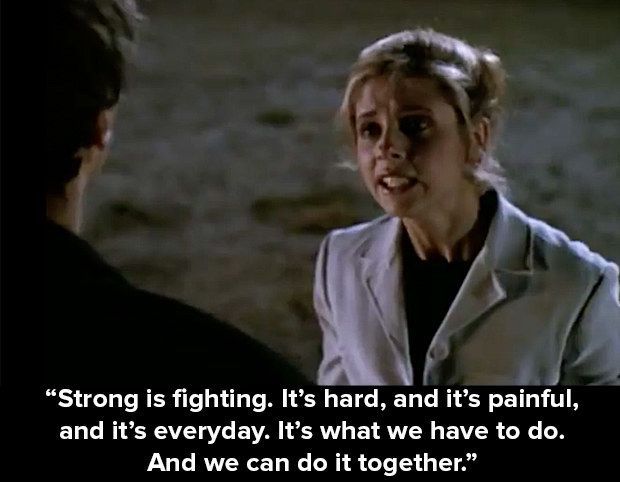

Camus’ (Camus’s?) foundational text in which he develops the theory of absurdism is The Myth of Sisyphus. I’m going to admit straightaway that I am not erudite enough to have read more than one essay from it. Much of my understanding of absurdism comes from Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Specifically, some very good scholarly analysis of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

Anyone who has known me for five minutes knows how much I love Buffy. I don’t think there is a piece of media that has shaped my consciousness as much as Buffy has. (Expect a post about that, or possibly a zine, in the future.)

In Ian Martin’s videos analyzing Buffy, he points out the connection between the philosophy of the series and The Myth of Sisyphus.

For those who are not huge nerds who remember everything they learned about Greek mythology in AP English Language, allow a summary:

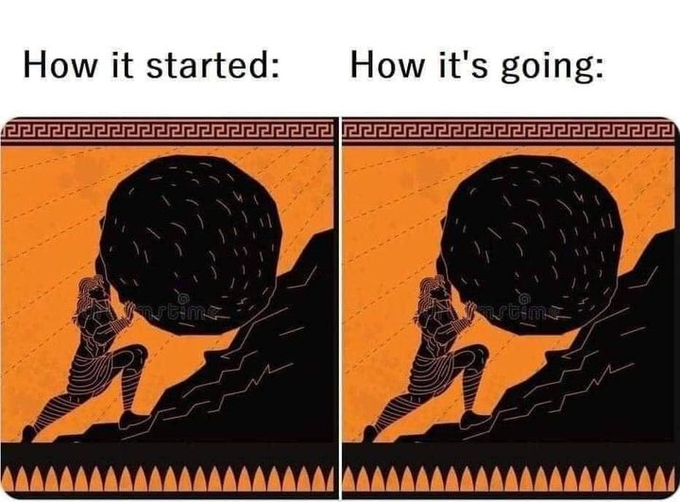

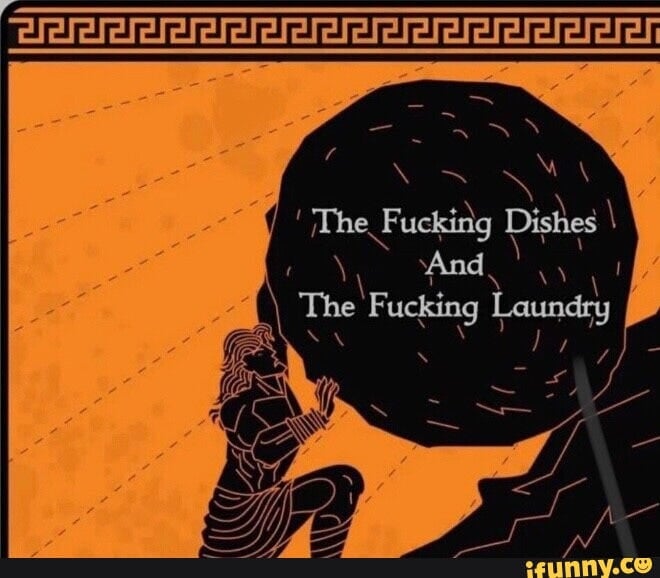

Sisyphus was a man cursed by the gods to spend eternity rolling a giant rock up a hill, only to have it roll all the way back down to the bottom. The moment he reached the summit, the boulder would crash back down and he’d have to begin all over again. Back and forth. Forever.

In his essay, Camus theorizes that it’s the moment when Sisyphus chooses to go back down to the bottom of the hill to start rolling the boulder uphill again, it’s that moment, when he becomes more than a helpless object in the universe. “At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock.”

(Thank you for staying with me here.)

Buffy’s power/burden as the Slayer is to fight an ever-replenishing onslaught of vampires and demons for the rest of her life, which is expected to be nasty, brutish, and short, like all the other Slayers who came before her. That’s it. That’s her deal. There’s no interventionist God in Buffy, no guarantee that she’ll ever be rewarded for her sacrifices or that others will be punished for their evil. No higher power is calling the shots or steering the characters toward a predestined purpose. But in continually choosing to save others, often at great risk to her own life, Buffy (the character) creates her own guiding principles that shape a meaningful existence— and thus Buffy (the show) illustrates how we might live an examined life.

In Ian Martin’s analysis of Buffy’s absurdism, he says that the task before all of us is, “Go and get your rock.”

As life grinds us down, as we accumulate sorrows with each year, when our plans disintegrate and our efforts seem pointless, we can still choose to cultivate hope just in the daily act of living, and to find fulfillment in that choice. Go and get your rock.

The brilliant writer, organizer, and abolitionist Mariame Kaba reminds us in her book We Do This ‘Til We Free Us that, “Hope is a discipline.” I think about this a lot, that hope isn’t a feeling that’s bestowed to us. It’s a direction we need to orient our compass towards in order to live in a world plagued by escalating fascism and climate collapse.

Kaba is known for periodically reminding baby activists and the newly radicalized that, despite the onslaught of horrors, it is always within our power to affirm life. That we can and should make these affirmations, no matter how small, because by choosing to live our values, we refuse the fascist logic that would have us abandon each other.

“You should take on the actions that you do because, at bottom, you believe that they are worth doing. I don’t know if the outcome of what I’m doing will be capital F freedom or capital L liberation. I think that the actions I take are worth doing in the present because they are a manifestation of hope in the day-to-day. They remind me of my and others’s humanity.”

-Mariame Kaba, as quoted in this Truthout interview

I cannot find any proof of this attribution because Kaba left Twitter after Elon Musk killed it, but I remember reading a tweet of hers that said, “Bring your pebble to the struggle.” She was telling people to stop waiting for the perfect conditions to act, to stop despairing about how overwhelmingly high the stakes were. Just bring your pebble to the struggle.

A friend said to me recently that she never predicted living in a time where the newspaper’s home page would have a sidebar featuring an ever-replenishing list of all the atrocious things the government was doing each day.

My anger and horror renew themselves daily, as I witness video after video of the world’s first live-streamed genocide, and as I grow ever more appalled at the way people and organizations in my close orbit continue to deny and rationalize that genocide.

The horror of a neverending day is what the people of Palestine are living now. It is what the immigrants trapped in the Trump administration’s concentration camps across the United States are living. Those of us who are not in Palestine, who are not in CECOT or the concentration camp in Florida whose disgusting alliterative moniker I will not repeat, have a responsibility to not give in to despair. While it is absolutely damaging to our psyches to see photos of shredded children’s bodies on our phones every day and know that our elected officials will do nothing to stop it, our own daily insistence on doing something, anything, to stop it, can be a countervailing force.

I don’t believe I will live long enough to see fascism fall for good, but I do believe I should act as if I will.

I can’t write a newsletter about rocks and pebbles without acknowledging the long history of Palestinians using stones as a means of resistance against the genocidal state occupying their land. Palestinians, who have been surviving and resisting annihilation for 22 months, but really for 77 years, have much to teach us about steadfast determination in the face of a cruel and powerful force that wants you silent or dead.

Those of us who are not living in the terror of possible death by U.S. bombs, quadcopter, IOF sniper, torture, or forced starvation, have to figure out how to make hope a discipline. We have to bring our pebble to the struggle. We have to go and get our rock.

“Wherever you are, whatever sand you can throw on the gears of genocide, do it now. If it's a handful, throw it. If it's a fingernail full, scrape it out and throw. Get in the way however you can. The elimination of the Palestinian people is not inevitable. We can refuse with our every breath and action. We must.”

-Palestinian poet Rasha Abdulhadi

The weeks following my father’s death were leaden with grief. There were days when the thought of never seeing him again pressed down on me so heavily that I could only lie on my back on the floor and sob.

There isn’t a, “but then I . . .” follow-up to that. I’m still carrying the grief. I don’t think I have been happy since he died. I don’t think I’ve been happy since I started witnessing a live-streamed genocide and a surprising number of people in my social circles jumped up to cheer it on or justify it.

There is no escape hatch from this time loop. I will wake up every morning to another day in which my father is not alive. I will wake up every day to a life in which I am not promised happiness. None of us are. The people in power are cruel and amoral, operating the controls of cruel, amoral, deathmaking systems. The charge to unseat those people and dismantle those systems feels insurmountable. Our reward isn’t guaranteed and neither is their punishment.

The temptation to quit, to escape, to numb, to indulge, to distract, to be bitter and callous, is strongest when I have not filled my own emotional reservoirs.

The actions I’m taking these days that are, as Mariame Kaba says, “a manifestation of hope in the day-to-day” are:

Fundraising for The Sameer Project and Gaza Funds

Organizing with my local mutual aid group, LA Street Care, to bring food, water, and other necessities to our unhoused neighbors

Serving on the Board of Women Who Submit; we just announced our decision to support PACBI, and we recently wrote a statement sharing resources for fighting back against ICE

Other pebbles that you, reader, might find worth carrying: writing letters to incarcerated people, donating to street vendor buyouts so immigrant families can stay safe from ICE terror, sharing Know Your Rights cards and Rapid Response numbers with your neighbors, picking up copies of The New York War Crimes and distributing them around town, and donating to the legal fees of people who are willing to take very brave, risky, criminalized actions against fascism.

We are not promised ease or joy. That’s not the deal. But the smallest gesture of shared grief with the people I love— including my family who are also grieving my father— is a lightening of the burden. And the simplest gestures of care toward the people that fascism deems disposable is enough to make me believe, even for just a moment, that humanity wins. We might not be as stuck as we think we are.

Camus closes one essay in The Myth of Sisyphus thus:

“It happens that melancholy arises in one’s heart: this is the rock's victory, this is the rock itself. The boundless grief is too heavy to bear. But crushing truths perish from being acknowledged. . . . The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill one’s heart.”

-

Yup. Rings true as can be. When we do what we can ....even in the face of it all...THAT is how ya live a life. I think of doing SOMETHING ANYTHING as... well - my clunky metaphor (I ain't no Camus) is that the regular brushing of your teeth is a practice we do that on the daily wards off minor negatives like bad breath and embarrassing little shreds of spinach AND in the long term prevents devastating tooth decay. When all your teeth are rotten and falling out it is hard to live right. So - to come back to the matter at hand - paying attention, SEEing and accepting the ugly truths, and doing SOMEthing every day is what I call moral hygiene. Thank you for this Newsletter. I love it.

-

Thank you for this multi-faceted view of all this. My English teacher in 12th grade assigned the Myth of Sisyphus essay to the class. He was a somewhat dour man—although my guess is he tried to have a good heart—and the big takeaway was “that fucking rock is going to be the end of me.” (Not that Camus actually said that, it’s just how it was taught and how at that time—17 years old and feeling powerless—I took it.) As I aged I saw that there is so much more. I love your consideration of the pebble. I still keep telling myself that a rock is really just a temporarily well-organized collection of pebbles, and it can be buried by more pebbles.

-

You had me at time loop cinema and their ultimate hopefulness. They're ultimately about breaking free. I struggle with nihilism and "go find your rock" is important advice. You're extremely perceptive. :)

Add a comment: