On comms consultants, big ballz, and the right's apology game

My Amtrak back from DC on Saturday kept getting stopped: signal problems, police activity, switch issues. Every time we’d grind to a halt I’d get a text message. “We sincerely apologize for the delay.”

While we twiddled our thumbs in the middle of Delaware after yet another issue, the guy across from me turned to the rest of my row. “The only thing Amtrak seems to be good at these days is apologizing. They apologize a lot!”

I nodded in assent, trying to respect the social boundaries of train talk. But according to researchers from the University of Chicago, it would’ve made me happier had I chatted him up. So what I probably should’ve done is told him that his joke made a really important point: the public apology has been hollowed out by overuse.

I have observed this often in this column, but I was heartened to read an excellent essay (even if it does steal my column title!) by Michelle Cyrca in The Walrus making a similar argument.

If you look for them, you’ll start to see statements everywhere, in the immediate wake of any scandal or public tragedy. The parties involved are shocked. They’re standing with victims. They’re listening and learning. Maybe they’re gesturing at doing something more concrete, but always at some indeterminate time in the future. This tends to go nowhere. The statement is all there is. Like an ouroboros, it exists only to swallow itself.

She writes later:

Forgiveness for mistakes should be possible in a just society, but it should follow from genuine remorse and reparations—not from outsourced platitudes wielded like a tranquilizer dart for outrage. As journalists and readers, we should be critical of a world where we are prevented from engaging with our representatives and leaders; where harms are direct but apologies are only offered at a remove; where we are told that the most authentic version of a person is the one drafted and approved by somebody else.

I would take this point one step further. The empty statement is not only unworthy of forgiveness, but actually precludes honest attempts at forgiveness.

In other words: with so much fake remorse, how do we differentiate what’s real? These days we are seeing Trump effectively using Steve Bannon’s technique of “flooding the zone” with so much chaos that it’s hard to respond to all of it. Something similar has happened with the public apology. Our zone has been flooded with, as Cyrca terms them, statements.

Where I disagree is the idea that these statements never had or have value. Cyrca argues that apology statements are disingenuous because a communications consultant class pens them, not the offender. As a former communications consultant who wrote apologies—I agree that in a better world we’d have far more journalists than comms professionals. And that hiring out your apology can often be a way for leaders to avoid confronting their own mistakes.

But plenty of off the cuff speeches are full of smarm, and plenty of ghostwritten speeches ring true. People can get help to speak from the heart. It’s just that, too often, they don’t bother to try.

Rather, the biggest problem is one of overload. Too many people demand statements. Too many people deliver them. And too many people reject them. So it’s too hard for us to sort genuine remorse from its phony lookalikes.

The reasons for this are myriad and ones I’ve covered before—the sincerity cycle, the weaponization of apology by bad actors, to name two—but in this essay I thought I’d discuss another ripped from the headlines: the different ways the American left and right currently understand the function of the public apology.

Last month, a DOGE employee (with the “you can’t make this up” online handle of “big ballz”) was outed for having posted racist content just weeks before he was hired to the federal government.

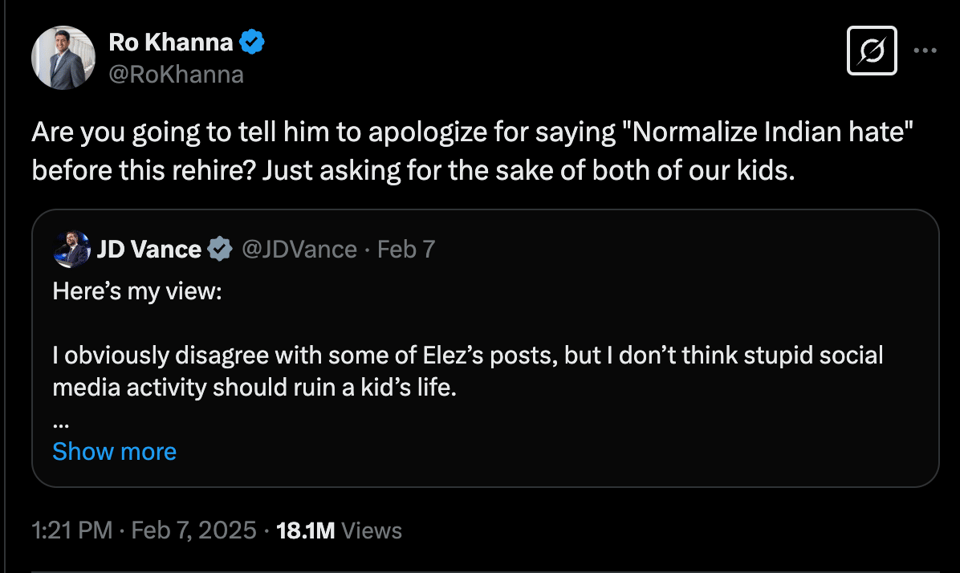

He was fired. Then the Vice President weighed in saying that “stupid social media” should not “ruin a kid’s life.”

In response, Congressman Ro Khanna asked a simple question: will “big ballz” be asked to apologize?

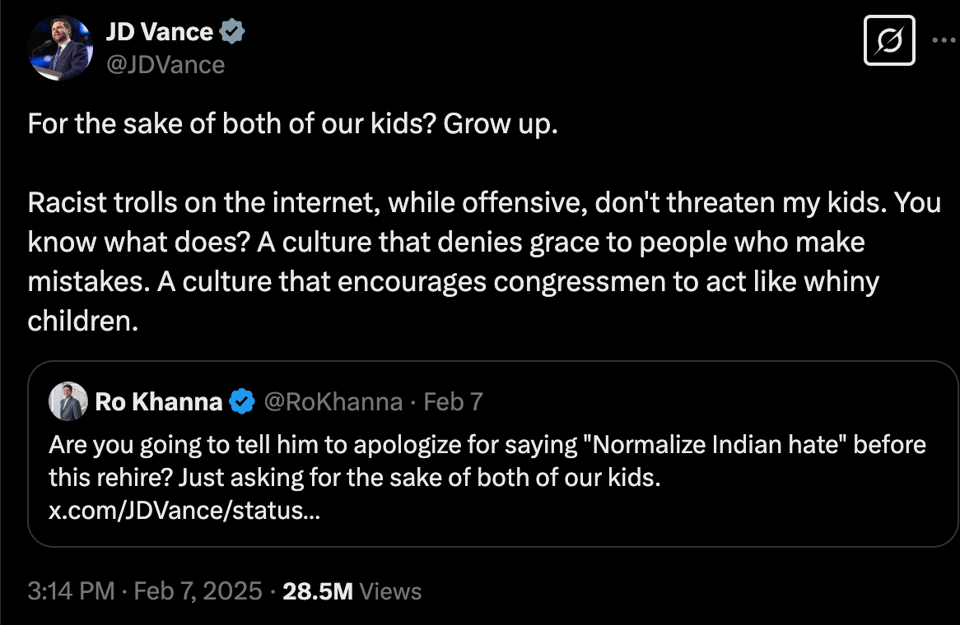

The Vice President responded by saying that Congressman Khanna “disgusted” him with his emotional blackmail.

Why? Because, in his words, we live in a culture that denies grace.

Now, as much as I disagree with the rest of his sentiments, I agree with Vice President Vance that the collapse of the public apology leaves little room for forgiveness and grace in our politics and culture. I mean, I literally wrote that as the second-half description of my McSweeney’s column.

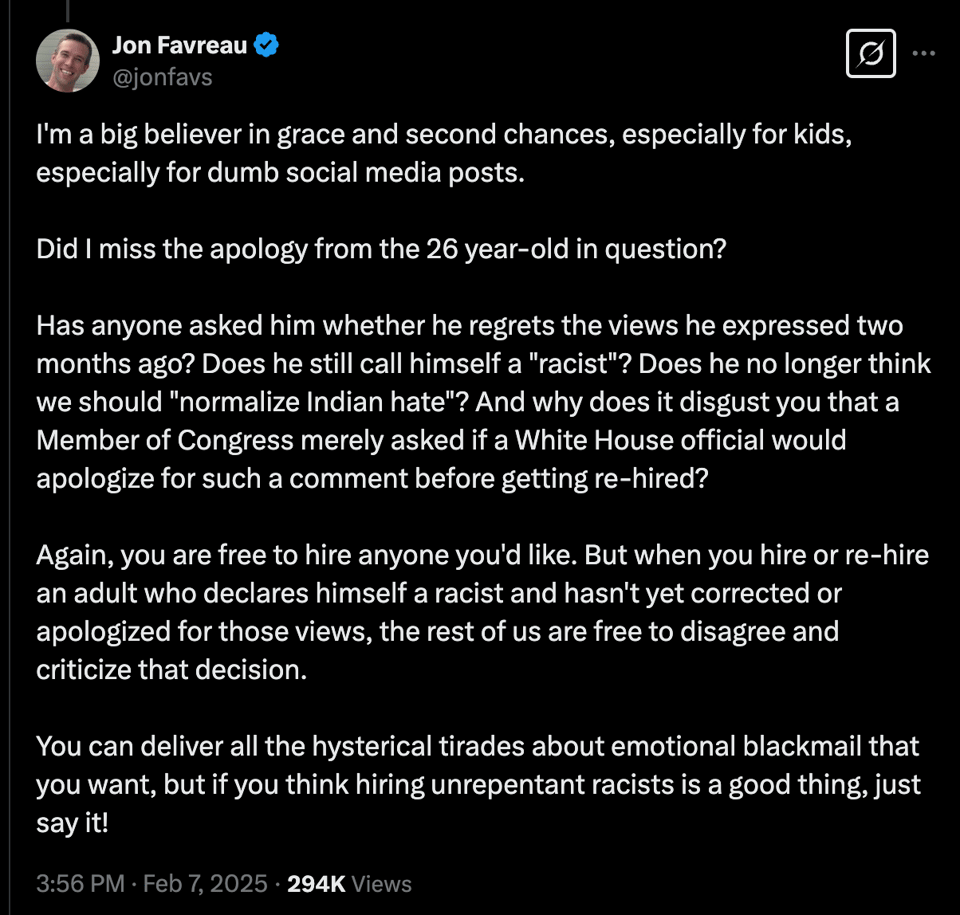

But, as the former democratic speechwriter Jon Favreau pointed out, you can’t blame the public for failing to accept an apology if you didn’t even try to apologize!

My dad would call President Vance’s attitude “pre-complaining.” You can’t pre-complain about the public apology not working until you’ve tried it first.

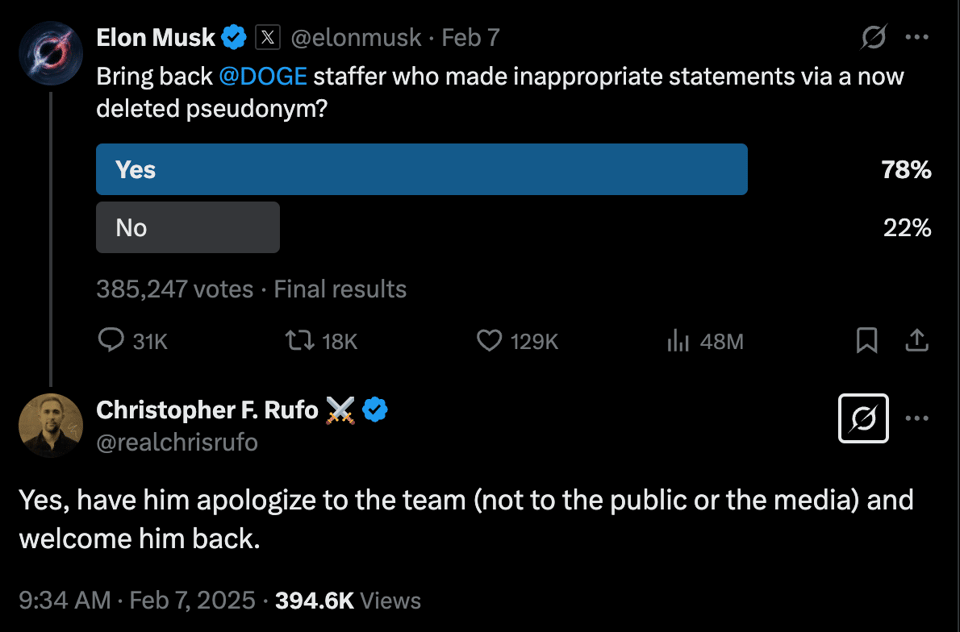

Except, well, if you’re on the right, you can. Because they’ve already given up on the public apology entirely. See below how Rufo, a leader on the cultural right, advocates for an apology—but to the team, not to the public.

Who “big ballz” should direct their apology to ought to be a question of who they wronged. Their overt racism was directed toward the Indian community—it would be natural to think he should apologize to them (us), and since you can’t apologize to all Indians or Indian-Americans privately, a public apology ought to be the only way to go.

That is, unless you think the only “wrong” thing he did was get caught. Then he should apologize to his team for having made a strategic error.

Now you might say, perhaps the right is consistent about this: they think public apologies are stupid and nobody should have to give them. “They’re against the puritanical cancel culture” you might say to be overly generous “and that’s a pendulum swing in a positive direction.”

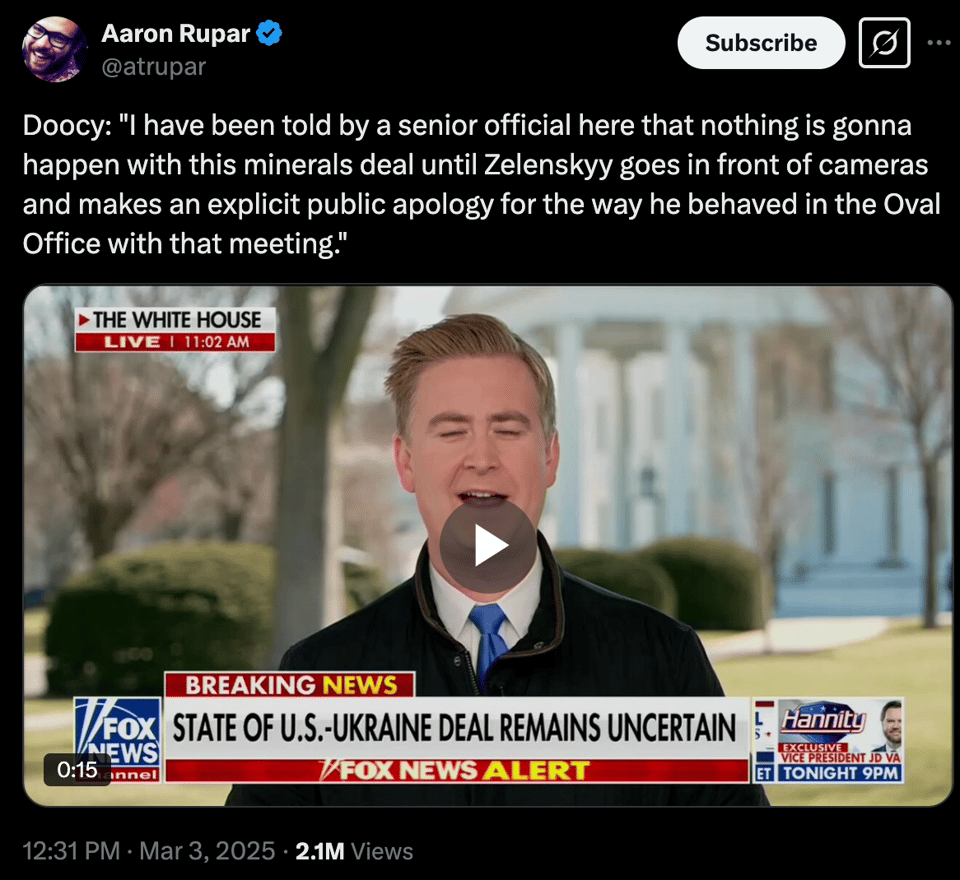

Except, well, this past weekend Trump demanded President Zelenskyy publicly apologize for not cowering before him in the Oval Office.

I will say give the right one thing: they understand the apology game much better than the left.

In the current state of our apology apocalypse, if you are being purely Machiavellian about it, the public apology is very much worth demanding—and should almost never be given.

p.s.

It’s been a bit since my last Sorry Not Sorry installment, but I have plans to expand this newsletter. For example, this will be the first post I share publicly online. And if you ever feel like somehow you’re not getting enough of my opinions, you’re in luck—you can hear my voice most weeks on the Riskgaming podcast.

Here are a few recent episodes to check out if you’re intrigued:

Danny Crichton and me discussing the ongoing collapse of the public commons and what this means for our personal lives

Danny, me, and Nick Smith discussing the role of luck in life, pedagogy, and public policy

Danny, me, and Christine Keung on DOGE and why we need more, not fewer, bureaucrats

Danny, me, and Maany Peyvan on why we failed to persuade Americans that USAID was the best thing about America