Last Week’s New Yorker Review: April 15, 2024

Last Week’s New Yorker, week of April 15

"She appeared not to have got much sun lately; I touched her up with a little blush."

This week is the Innovation & Tech issue, a theme which didn’t immediately inspire much confidence – I braced for A.I. indulgence – but which produced a very strong issue, with four solid features that complement one another without feeling contrived. Total sidenote: My paper magazine had a printing issue in which a number of the color pages seem not to have any yellow, especially noticeable with the (excellent) spot-art for the Anna Wiener piece. (I’ll post an image at the bottom.) Has this ever happened to you?

Must-Read:

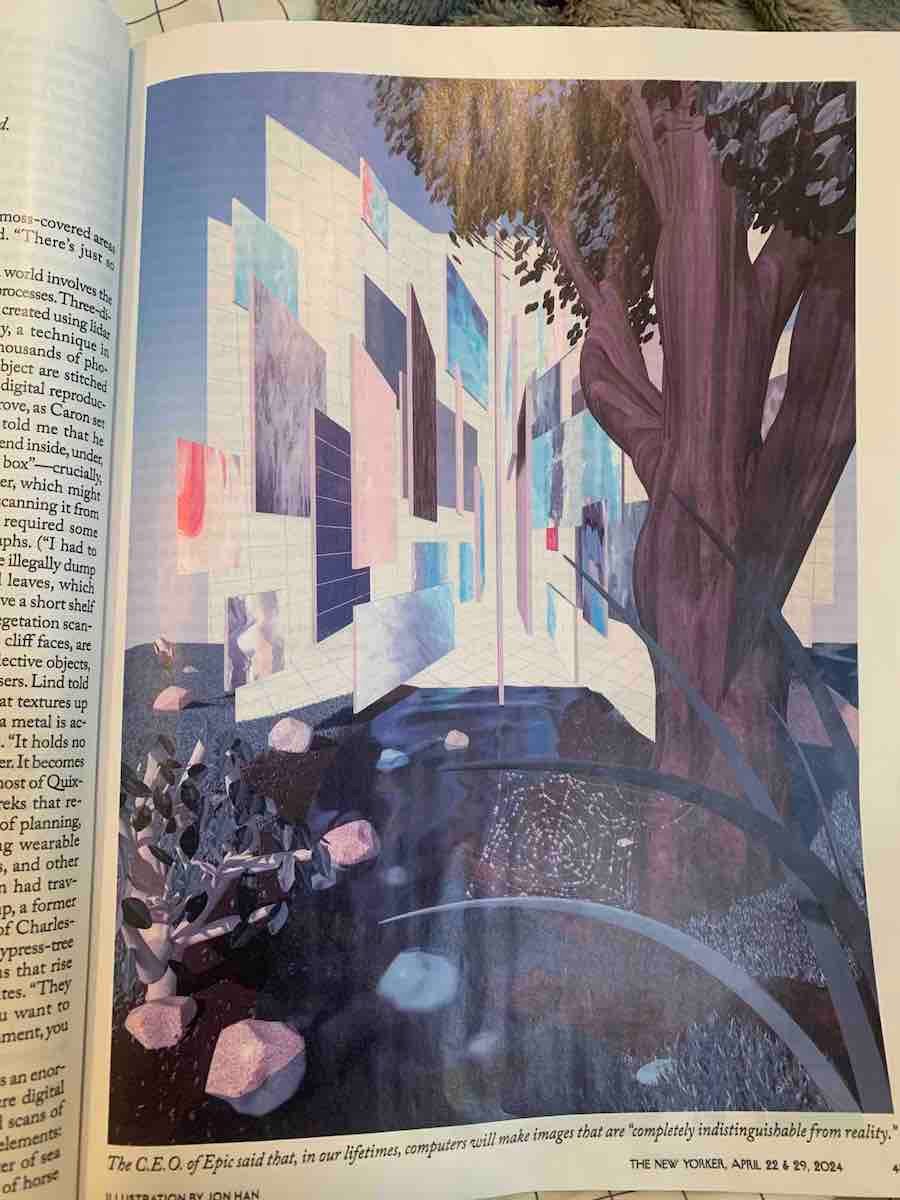

“Get Real” - Anna Wiener scans a redwood with the software developers shaping the digital world. Basically the platonic ideal of a tech story. I knew Wiener was thoughtful; I didn’t realize she was quite this funny. Inspired by the scan-and-catalogue obsessiveness of the teams she profiles, Wiener fills the piece with a cornucopia of perfectly described weird objects (“an aggressively roasted turnip”, “a digital asset of her orthodontic retainer”, “a humongous doll wearing a kicky bathing suit”, “a kind of anthropoid slurry”, “a plastic fiddle-leaf fig”, “a dial labelled ‘SCORCHING CAR SCALE’”, “fat chocolate-chip cookies,” “the drainage pipe at the edge of a clearing”) each of which I pictured rotating in a digital void. What makes this topic difficult is the blurry line between the micro-subject, texture-scanning for a very specific piece of software, and the macro-subject, the virtual world and its implications in general. Wiener is careful not to lose the former in the latter, but neither does she pretend not to have other things on her mind: The climate crisis keeps cropping up, which could feel distracting but instead feels like a reminder of the stakes of physical life; the “military-entertainment crisis” comes in for a mostly implied but still cogent critique; and Wiener’s main argument, that this stuff isn’t confined to videogames but has already saturated our whole social landscape, is made ably and with neutrality (but still pep and a point of view.)

It helps that the subject matter doesn’t require any speculation to look important – this is already happening, it’s a genuine shift, and it’s not widely understood. Wiener finds a vein of deep absurdity in the topic: A “debris box” must be scanned instead of a “branded Dumpster, which might not pass legal review”; there’s a subculture around “texture archaeology” which involves inspecting and admiring the “illusion of shininess” on Mario’s hat… those are just from the first section. Yet she always maintains a certain respect for the work; the humor doesn’t mock. A late reference to an “edible” clicked it into place: Wiener writes like a hyper-intelligent stoned person, breaking into joyful giggles at her own close observations. Call it high-resolution.

Window-Shop:

“What Is Noise?” - Alex Ross appreciates the feedback. I have a few quibbles with this piece, but I feel ungrateful: It’s not merely Alex Ross writing in a roving, discursive style; it’s him doing so with balls-to-the-wall energy, amounting to a testament to the importance of noise as an idea. It reads like the introduction to a book on the topic, and it’s a book I’d like to read. Ross opens things confusingly, though, going after “noise” as a word, and immediately exploring the furthest reaches of its meaning in a manic style that feels designed to obscure the “Webster’s Dictionary defines…” enterprise at hand. Ross quickly narrows things down, in the next section, to noise as music in particular – before then expanding things again, and then re-narrowing them. Ross seems flustered and annoyed by his task in the more expansive sections, which are both brief and scattered; the section on “informational noise” is especially immaterial – which is not to say uninteresting; Ross still finds novel tidbits on the Klaxon horn and the “irony” of electrical noise’s dissipation.

Push through, though; once Ross relaxes into experimental music and the strange wonder he finds therein, things really spark to life. The history of noise in music (“all twelve pitches” at once causing a riot in Vienna, Jazz that “not only cut through the crackle of surface noise but also thrived on it,”) is very concise – each line could be a chapter in that book – but still potent; the climactic attempt at defining the aesthetics of noise are fascinating. Ross articulates noise-as-otherness, as escape from any “universal language” that tries to draw a clear line between music and what’s outside of it. “No one chooses to listen to a sound because of what it is not” – you can meditate on that koan.

“No Time to Die” - Dhruv Khullar goes rucking crazy with life-extension extremist Peter Attia. Has there ever been a less trustworthy backstory than this: Trained to be a surgeon, “grew disillusioned,” “became a consultant for McKinsey instead, and then worked for an energy company.” That’s some disillusionment. Did he get into health food while he worked for a company that was fixing bread prices?

Anyway, Attia’s horrific business, offering overly invasive healthcare to the very wealthy, comes in for a fairly predictable but still entertaining nitpick from Khullar, who basically represents the medical establishment in these pages, but who’s picked the right enemy in this case. Attia wants to replace “First, do no harm” with his own process, which amounts to “Move fast and break bones.” He’s a fairly unpleasant person to spend time with, and Khullar keeps things studious and precise, which also means granting him a lot of leeway to spread his bullshit. I wonder if the magazine’s usual give-them-enough-rope style doesn’t sometimes blunt pieces like this; comparing it to the far more vicious NY Mag blast of a similar pop-science douchebag makes Khullar’s restraint a bit frustrating (although, to be fair, while Attia’s personal life is barely covered he hardly appears to be a serial manipulator.) Khullar psychoanalyses Attia a bit, bringing things to his counterproductive “worship” of longevity, which seems more “tangible” than other gods, but it’s all couched in forgiveness (“there are worse gods”), not fire and brimstone.

“How Gullible Are You?” - Manvir Singh says okay, ladies, now let’s get misinformation. Singh seems very pleased by the catchiness of his premise, which he repeats twice: We’ve been misinformed about misinformation! Namely, the glib pop-psych formulation that we’re easily manipulated, highly credulous, and totally trickable is all wrong. Instead, we sort truths into “factual” and “symbolic” beliefs; we hold the former to high standards of facticity while the latter are mostly useful as group signifiers. This all strikes me as a pertinent correction to a widely held idea – but somehow Singh never quite considers whether the misinfo about misinfo is a case of writers getting their facts wrong, or whether there’s a more symbolic force at work. Who profits from a fundamental conception of people as foolish? For one thing, those whose politics are authoritarian; an easily lead populace demands a powerful, benevolent leader. Politics in general are really what’s at hand here: Political views which are held as “symbolic beliefs,” as primarily markers of group identity, have the privilege to think that Democrats are all secret pedophiles or that our country ever truly quarantined from COVID. But when you’re directly impacted, these issues are suddenly factual, too: Your trans kid might not make you less transphobic as a matter of policy even as you care for them as a matter of parenting. The real issue is how to make people truly understand that the personal is political – or, in other words, the symbolic is factual, in that symbolic beliefs have tangible impacts on our factual world. Unfortunately, the increasing immateriality and alienation of our social world make getting that point across ever harder – the question isn’t how to make people believe the world is round, the question is how to make people believe the world has other people on it.

Special Section: All-excellent Talk of the Towns this week, so let's bring this feature back (which I'm gonna center-justify just to differentiate things.)

"Forensic Fury" - Rebecca Mead attends to the Grenfell chorus. Grim and powerful.

"Here Today" - Michael Schulman does some kingside sandcastling. Cute. Excellent button.

"In the Stacks" - Naomi Fry reshelves VHS tapes with the cinephiles sorting through Kim's Video. I knew of these people already, so I was predisposed to enjoy this, but even so it's hugely charming and covers a lot of ground without fuss.

"Short-Term Lake" - Meg Berhard paddles while the paddling's good. Provides both neat today-I-learned info and a well-proportioned story – with a grisly interjection!

Also, last week had a good Talk which I left out of the edition due to an editing error:

"Earthquake Notes" (Talk of the Town) - Sarah Larson is all shook up. Very quick turnaround – and an uninflected charm, perhaps as a result!

“Warp Speed” - Jackson Arn sees what a tangled web Anni Albers weaves. Quite good on Albers’ weavings, their “loaves-and-fishes abundance,” lines with the “wincing firmness of surgical stitching” or “a lovely softness and shimmer.” Not so good on Albers’ prints, which have a “gleeful bounce” that doesn’t really read when Arn is recounting the exact rules by which they’re composed. Skeptics of Albers’ pivot are quickly dismissed with a “get over yourself”: I like Arn’s spunkiness. Not much on its mind beyond the joy of looking, which is perfectly fine!

“Snap Judgements” - Justin Chang doesn’t need Alex Garland’s Civil War. Chang struggles to find a point to this misbegotten movie, straining a bit with the effort – maybe it’s about the power of journalism? His convolutions are entertaining; less so is his plot synopsis. After he admits that “the plot comes at us in a rush of details so clipped and vague that you can’t help but suspect that they’re largely irrelevant,” he spends three long paragraphs recounting those details anyway. Why?! Just say there’s fire and blood and be done with it.

“Flight of Fancy” - Gideon Lewis-Kraus lets one fly. I’m not sure if nabbing your framing device from techie reactionaries (“Where’s my flying car?”) is such a good idea if the ultimate beat in your story is that flying cars are actually really cool. I waited most of this piece for the other shoe to drop, for the environmental impact to be revealed as not-so-light (it’s barely mentioned, but apparently it really is light, at least compared to the alternatives) or the focus on figurative-pie-in-the-literal-sky innovation to have taken both excitement and resources from existing public-transit initiatives (Lewis-Kraus gestures toward this possibility, but concludes that “public transit is a political problem, not a technological one” – a different allocation of resources wouldn’t solve the basic issue.) Ultimately, Lewis-Kraus does an excellent job showing how there are two forces at hand: A desire to make flying cars because they’re frickin’ cool, and a desire to find a use-case for flying cars so that they can get frickin’ made. But the use-case just isn’t clear, given some major technological limitations, so Lewis-Kraus’ focus on that side of things never stops feeling like a pitch meeting where desperate engineers try to raise funds. The other side of things fares somewhat better; the essayistic snippets of Lewis-Kraus dealing with his family’s reactions to his risky missions reminded me of the wonderful A.J. Jacobs, and the flight-simulator scenes were fun too – though only the second-best flight simulator scenes in the issue; see: the must-read. There’s just not enough of those scenes to right the balance.

Lewis-Kraus’ prose, when he makes time to showcase it, is characteristically strong, but this piece is very heavy on quotes, most of which consist of technologists muttering about the possible, theoretical importance of what they’re doing. They’re never very convincing. The real utility of this technology, for now, is pioneering new frontiers in midlife-crisis indulgence; many of this magazine’s readers may find the euphoric climactic description of the BlackFly flight quite compelling in that regard.

"Bleeding Heart" - Amanda Petrusich gets gutsy at the Olivia Rodrigo concert. Petrusich's cheeseball stylings ("at least no one whispered 'narc' when we walked by") are a fairly good match for Rodrigo's theater-kid performance of punk (which is brilliant, I hasten to add.) Whether she has much to add to the burgeoning field of Rodrigo studies is a more open question; she mostly rehashes the conventional wisdom ("She never projects superiority.") But the magazine's pop-star coverage is paltry enough that this still feels refreshing. Petrusich's overexplanations of Rodrigo's lyrical punchlines, though, are so cringe (as a tween might say.)

Skip Without Guilt:

“The Missing Link” - Maggie Doherty frames the famous life and forgotten work of haunted modernist Delmore Schwartz. It’s unfortunate, since Doherty’s entire thesis is that Schwartz’s poetry deserves more coverage and acclaim, but this piece is at its best when discussing Schwartz’s personal travails. There, Doherty is deeply feeling; She untangles the very hard problem of connecting an artist’s mental health to their work with grace, writing elegantly that Schwartz “struggled with a mood cycle marked by high highs and low lows; the former took away his powers of discernment, and the latter left him struggling to write at all.” Doherty struggles to make Schwartz’s work come alive on the page; a block quote of supposedly “the most affecting lines he ever wrote” did nothing for me, certainly a bad sign. She makes the odd choice to pair the good stuff in his late work with the worse stuff in his earlier, more acclaimed work, thereby bringing both eras down. Her exegeses are never particularly elegant; she remarks that the contrast of the “bare” soul with the “bear” body suggests “a duality that can be reconciled only in art,” which could fairly be said of any duality. Perhaps, in this case, history’s vicissitudes got things basically right: Schwartz had a fascinating life, and so-so work. Too bad.

“Love Machines” - Jennifer Wilson leaves A.I. hanging on the telephone. [^1] Things start bad: “Rizz” is obviously not Gen-Z slang, it’s Gen Alpha slang! Wilson proceeds in a cutesy-jokey style throughout – and, look, I’m one to talk; have you read this newsletter lately? – but still, I find it tiresome. Still, the first review is quite incisive, rightly picking apart how the story’s simplification of both male and corporate motives leads it to unsavory political implications: “conflating bots with women misunderstands the nature of misogyny… abusive men are not motivated by sex, but by the desire to inflict harm on real women.” Spot-on. Unfortunately, the second review mostly rehashes the same points in less potent terms, and the conclusion finds nowhere novel to land. Just read that second section, then drop the receiver.

Letters:

Regular correspondent Michael liked Rebecca Mead’s piece on slouching, but wishes “it was longer.” He adds that it might get him to read Stand Up Straight!: A History of Posture, “a book I purchased after being intrigued by its title in a book catalogue.” Who hasn’t been there?

He also highlights a ProPublica piece “on the poor conditions of commercial trash collectors”, which covers some of the same material as Eric Lach on trash collecting.

Red leather, orange linker. Red leather, orange linker.

This week in the outside world: I have COVID. Sad!

[^1]: That Blondie song has been my bop of late. One of the great vocal performances of all time.

Add a comment: