Cons & Heists 101: The Score and the Mark

Here's the thing about con and heist stories. They can be serious, ironic, comedic, post-modern, supernatural, mundane. As we discussed last time, cons and heists are less a genre in the traditional sense than a type of story problem-solving. Cons and Heists have their own structures, but they are united in their goals -- taking a Score from a Mark. In fact, if one sees all con and heist stories as having similar structures, than the variations of the Score and Mark are what make your story different. They define your story, not the clever perambulations of your plotting or gimmickry.

The Score

The Score is something of value that belongs to someone else. We would like it to belong to us. But ...

Why is it valuable?

The first order answer to that may be "Well, obviously, because it's a giant pile of money. Or diamonds. Or a fancy painting."

Per Rule 1 of Crimeworld, "Where there is value, there is crime," we can go even further. The Blood Avocados of Mexico. The black market of Venus flytraps. Rare large-eyed dolls. A one-of-a-kind yeast, the source of a specific culture for a specific rum. Bull semen. The last violin played on the Titanic. Low background radiation steel. That one's pretty ungainly, but I just love it, and it's my newsletter. The relentlessly clever screenwriter Jenn Kao won her spot on the LEVERAGE writing staff with one sentence: "I want to write a classic diamond heist, but the diamond is an open-source potato."

Virtual items too, and not just digital monkeys and secret code but simple unadulterated data sets. AI is poisoning itself as it samples its own trash, an ouroborous of uselessness. Never mind the data that's being intentionally poisoned by artists, and good for fucking them.

That's not bad, having an offbeat object of value. You can get a halfway decent story out of that. But it's better to ask the next question:"Why does my protagonist need the Score?"

"To pay off my kid's medical debts, to get information that can clear my name, to ruin the Mark's reputation ..." Some sort of emotional investment.

Better. And then the final, best question: "Why does the Mark need the Score?" If they don't need it, if they're so rich they don't care, or it's emotionally meaningless to them, fine, you're kind of writing a protagonist vs. institution story there. But it's better if the Mark needs the Score too. Even better if they need it for different reasons than your protagonist. After all, a good story is a collision of needs. Often you can get away with that collision occurring solely among the members of your Crew, but it's juicier if that Score has not just value but a different value to your opposition.

That value can be metaphorical. A bank doesn't care about the money you're stealing. But banks represent something. Conformity. Control. Power. Corruption. The State does not always care why or what you're stealing, but it often needs to prove quickly and harshly that it will not broach the disorder implied by the fact that you can steal from it. If the State is the group with a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence (or power), any challenge to that monopoly is dangerous. The institution can be represented by a character who embodies the system, so those needs become manifest (hello, ANDOR.) and the storytelling made more interpersonal. Heist and con movies live in class conflict. Even if it's not about the Poors vs. the Rich, power defines value, and where there is value, there is crime.

Is the Score a Tool — something used on a regular basis for some larger purpose — or a Treasure — something locked away, rarely taken out, and valuable solely because it is possessed? Is it a Tool for you but a Treasure for others?

You've probably heard of a MacGuffin. It's a term allegedly invented by Hitchcock, shorthand for the object that triggers the plot. Triggers, but does not drive. A MacGuffin can be a useful thing, but a collision of needs is a better foundation.

The Mark

Now hold on. If the Mark's my villain or active antagonist, and that's where all the story juice comes from, why did I start with the Score?

It can work both ways, but for me, often the Score helps define my protagonist's needs (always good) but also then creates a setting for my antagonist and their need. From there I can reverse engineer a unique antagonist, rather than fall into the trap of writing my pre-conceived villain. Personally I like falling backwards into my bad guys. If the Score is unique, my protagonist's need for it is creative, and my well constructed Mark's opposing need for it is similarly offbeat. And their need gives me and angle on their desire, which often gives me their sin.

There's an old screenwriting truism, "You character should set out to get what they want, but wind up with what they need." But want is, well, wishy-washy. It's soft. The philosopher Simone Weil (the better Simone) in her book The Need For Roots differentiates between needs and desires, in that needs "... must never be confused with desires, whims, fancies and vices. We must also distinguish between what is fundamental and what is fortuitous." A need can be filled, a need can be sated; a desire never can be. A void that can't be filled drives compulsion, compulsion leads to sin.

Which is where we really wanted to get to. Crime stories are fine, stories about sin are better. A desire, leading to sin, is useful because it's not only motivating the villain, it's also their weakness, and the path to their most cathartic downfall. A Mark will not just do ugly things in pursuit of their desire, which will let our audience hate them, but they'll also make mistakes in their pursuit of a desire, because their desire overrides their caution and good sense. This also gives our heroes their way in, their attack vector. It's a threefer!

You can do worse than to slot your Mark into having one of the Seven Deadly Sins. Wrath is not just anger, it's excessive anger -- but also spite, revenge, even obsessive justice turned sour. Greed is on obsession with material things, an almost mundane sin but useful to have in the toolbox. Sloth is not just laziness. In medieval times Sloth was understood to include the sin of spiritual inactivity, of standing by and letting bad things happen. A Slothful Mark takes shortcuts, looks the other way so long as they get what they want. Lust is intense desire for a specific need. Greedy Marks want more stuff; lustful Marks crave one thing.

Envy is also desire, but specifically for what other people have. This can involve not just possessions but status. Gluttony is overconsumption and indulgence. A Wrathful Mark needs to destroy his rivals; a Gluttonous Mark needs to own them.

Pride, or excessive self-regard, is considered the original sin, the source of all others. Hurt Pride leads to Wrath, for example. Pride is the Mark’s sin in the classic con movie THE STING. In this story the Mark is crime boss Doyle Lonegan. When Lonegan’s conned in the opening act his hurt pride leads him to violently murder one con artist and send the other — Johnny Hooker — on the run. When Hooker teams up with the infamous con man Henry Gondorf, they suck Lonegan into their scheme by not just cheating him at cards, but cheating him at his own rigged game, tweaking Lonegan’s Pride in his own criminal skills.

The Mark is not usually alone in their world. It's often useful to determine if the Mark has:

AIDES: Do they have Enforcers or Experts who work for them?

ALLIES: Who does the Mark trust? Who do they work with, not for?

ENEMIES: From friendly rivals to deadly opponents, against whom is the Mark set? Who do they wake up every morning hating, scheming, counter-scheming against?

AUTHORITIES: Who does the Mark answer to? Who will make the Mark sit up and take notice, make them nervous, force cooperation?

Is your Mark so powerful they answer to no one? Well, believing that can get them stripped of $56 billion in compensation by a nice judge in Delaware. Even if they're not afraid of the authorities, what are the tigers they avoid poking, if they can help it?

No matter how you attack your story — through theme, through your protagonist's needs, your Score, or your Mark, doing your best to tag all the bases on each element will bolster your crime framework to support your main story.

Next time, we'll start with Heists. How to Run the House, Crack the Box, and Dodge the Heat.

********************

If you were sent this newsletter by a friend or followed a link here, and it seems like we're your kind of wordsmithing, why not subscribe?

********************

Reviews and Recommendations

Criminal — podcast

I first stumbled across the Venus Flytrap story ten years ago on the excellent crime podcast Criminal. They've been tooling along for a decade now, providing you with a nigh endless source of stories about every corner of crime, the perception of crime, the world of law enforcement, etc. It's a bloody treasure trove.

Darknet Diaries — podcast

Jack Rhysider has been turning complicated, obscure cybercrimes into easily accessible, compelling thriller narratives for seven years now. 142 episodes on the new(ish) frontier of crime, each one both inspiring and terrifying. I'm not the first to compare the virtual world to Olde Magick. We made a set of rules that control physical space, but certain people can manipulate those imaginary rules in ways many of us simply can't understand.

"Seven People Hold the Keys to Worldwide Internet Security" - article.

Four times a year, an international group of people arrive at a physical location with their secret keys, and they reset the entire goddam Internet. If they don't ... bad things happen. Very bad things.

Was I asked to write a cool little cyberthriller mini-series about this? Yes. Did it work? Not really. But this article is a great example of one of our recurring themes here on the newsletter: physical systems we interact with on a personal level, and their relationship to larger systems and abstract concepts. Pressure points.

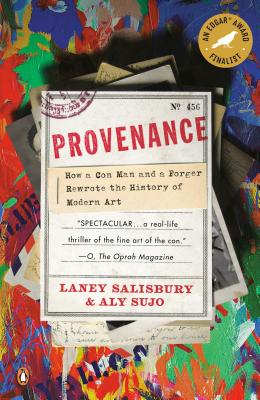

Provenance: How a Con Man and a Forger Rewrote the History of Modern Art by Laney Salisbury and Aly Sujo

So far we've tagged the Long Con, Bank Robberies, and Money Laundering. We of course need to get into the sexy stuff. There are a million art forgery books, but this is one I particularly like. It examines the interplay of the forger of actual art and the far harder working, more subversive forger of provenance — for the uninitiated, the documents verifying (directly or indirectly) the legitimacy of a famous piece of art. LEVERAGE:REDEMPTION viewers may remember we made this distinction with one of Sophie's old friends, that his forgeries were mediocre but his paperwork was flawless. Again, this book is lousy with systems and their flaws, my particular popcorn.

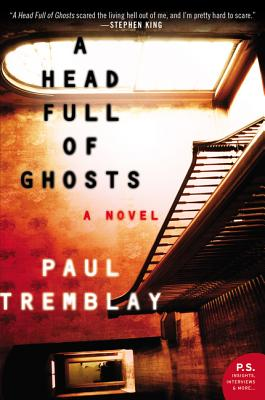

A Head Full of Ghosts by Paul Tremblay

An adaptation was recently announced for this, which gives me an excuse to put forward my personal favorite ghost story book. Scary, sad, clever as hell in its narrative construction, with one of the few endings that left me puzzling out what it meant, but without any feeling of incompletion at all. It ended right, and left a hanging question I genuinely enjoyed dwelling in. I'm not sure an adaptation can even do it justice, but I'll enjoy watching them try.

********************

Stay safe until next time. Your cheap advice this week is to remember the world is an infinite ocean of pain that will sweep you away and drag you into its crushing midnight depths if you step just ten feet from the shore. So being careful about your media intake is not cowardly, it's self care.