The Perpetual Battles of “Golden Rage”

Exploring the haunting landscape of Chrissy Williams and Lauren Knight's dystopian graphic novel "Golden Rage."

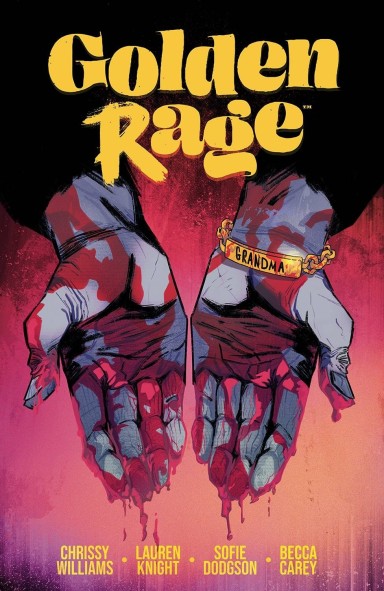

The cover artwork for Golden Rage is immediately striking: two hands dripping with blood, with a bracelet reading “GRANDMA” around one wrist. That combination is not a dream, not a hoax, and not an imaginary story; once things are underway, Jay — who narrates the first issue — describes herself as “surrounded by grandmas turned murderers.” That phrasing doesn’t necessarily describe the full scope of the dystopian society in which Jay finds herself, but it’s also not incorrect.

Golden Rage, from writer Chrissy Williams and artist Lauren Knight, is about two things: clashes between communities and the aftermath of complicity. The island setting of the book is home to several distinct factions, including the violent Red Hats and the Dead Women, who care for the bodies of the deceased in silence. There are also smaller groups on the island, such as the trio of women who take Jay in shortly after her arrival there: amicable Lottie, profane Carolina, and taciturn Rosie. (There was once a fourth, Mary, but she died before the story began.) There’s also a society that the reader never sees on panel, and it’s one that looms over the proceedings: the nation that exiled these women due to their infertility.

The characters in Golden Rage can remember a better time; Caroline, who’d previously worked as a creative writing professor, visited the island before it was, essentially, a prison colony. At the time, it was an artists’ retreat, and from the moment when she reveals that, it’s hard not to see how this battlefield would have looked during more peaceful times.

There’s something profoundly wrong about an idyllic retreat turned into a killing ground; it’s as discordant a shift as, well, the bloody hands on this book’s cover art. There are more moments of discord throughout the book, and they occur unexpectedly. Early on, there’s a debate over the effectiveness of a spork as a weapon; later, the book’s central quartet encounters a dead body, the result of a knitting needle driven through the chest.

Each of the three women with whom Jay takes refuge has useful knowledge that pertains to the island. For Lottie, it’s a penchant for the flora and fauna around her; her thoughts occasionally drift to the chickens she raises. For Caroline, it’s knowledge of the island’s geography and history. And for Rosie, who’s prone to the occasional outburst in Italian, it’s sheer physical prowess; one gets the impression that she could probably take on the rest of the island’s inhabitants and win single-handedly.

Jay narrates the first issue, while each of these three women handles those duties in the subsequent chapters. And while Jay’s narration is fairly straightforward — which makes sense, as she’s the newcomer to this setting — each of her three companions takes that in subtly different directions. From a formal perspective, this is most apparent when Lottie takes on narrator duties. She’s prone to digressions and anecdotes, to the point where her narration covers other characters’ dialogue. It’s a memorable evocation of being so lost in one’s thoughts you don’t quite pick up on what’s happening around you.

Still, there are signs that something bigger is happening here — and that there’s more to Jay than simply someone who’s run afoul of an authoritarian regime. While the four women never stop being at the center of this story, its focus gradually expands to take in other perspectives and to reveal conflicts old and new from different angles. It hearkens back to the shadow of the society that exiled these women and their occasional references to their positions there. All of these women have witnessed the country where they lived transformed into an authoritarian regime; all of them have wound up in a position to be punished by that country. And some, it transpires, had a more active role in that than others.

Williams’s script abounds with dramatic shifts in scale and scope, with reversals and changes in power dynamics across the whole of the book. There are also some fantastic lines, including, “You can’t pick your mum, but you can overcome her in hand-to-hand combat” and “Bloodshed and murder aside, this is the most supportive community I’ve ever been part of.”

Knight’s art, meanwhile, is stylized without ever turning cartoony or caricatured. Where she excels the most is in drawing a cast of characters with a variety of very different bodies. Knight also illustrates some memorable fight scenes, though perhaps the highlight of the storytelling comes in a surreal interlude in which Jay watches a pair of clowns enact a strange routine. It’s a memorable example of wordless storytelling, and it also serves to tell the reader something about the characters taking it all in.

Golden Rage ends on an ambiguous note, with some tensions resolved and others on the horizon. The fact that there’s a “1” printed on the spine of this book suggests that readers haven’t seen the last of these characters; if future volumes contain a similar balance of visceral action and thoughtful debate, I’ll be thoroughly on board.