“The Hunger and the Dusk” and the Art of Subtle Horror

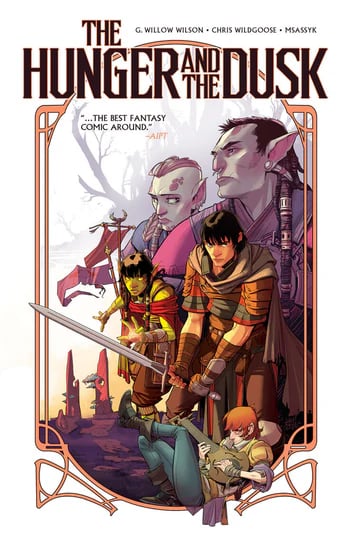

"The Hunger and the Dusk," from G. Willow Wilson and Chris Wildgoose, blends fantasy and horror in unexpected ways.

Sometime during the pandemic, I ended up sitting down to play The Banner Saga trilogy of games, due in no small part to Luke Plunkett’s writing on the series. The games are about a series of unlikely alliances between different cultures to avert an apocalyptic event. In his review of the third installment, Plunkett described the way the game evoked “the desperation of a last stand.” And of the better compliments that I can pay the first volume of The Hunger and the Dusk, from writer G. Willow Wilson and artist Chris Wildgoose, is that it taps into a lot of the same emotions I felt when playing said game.

After a short prologue — more on that in a moment — the book establishes the two parallel plot threads that run throughout. After a long period of conflict between humans and orcs, the arrival of a new threat has led some within those communities to seek an alliance. And so Tara, cousin of orc leader Troth, joins the Last Men Standing, a group of human fighters led by adventurer Callum. As for Troth, we also see how he and his fiancee Faran — also a skilled fighter — battle this new threat for themselves. Throughout, the quartet must also reckon with some of the political fallout from the human-orc truce.

That’s all well and good — and as an admirer of the likes of Robin Hobb, George R.R. Martin, and Katherine Addison, I’m always up for political dealmaking overlapping with swords and sorcery. There’s plenty of action here; three of the book’s four central characters are capable warriors, and even Tara’s skills as a healer have an use in battle besides healing the wounded — she can drain the life force from her adversaries to do so.

If you’ve read the above and think, “Gee, that’s a surprisingly nasty application of a healer’s abilities,” you’re not wrong. And here’s where we return to the prologue, and where I make my central argument: The Hunger and the Dusk might look like a fantasy comic, but the story that it’s telling is a lot closer in tone to horror.

About that prologue: it follows two groups — orc fighters and human farmers — as they seem fated to collide with one another. There’s no love lost between either group, and Wilson’s dialogue gives dimensions to both sides, right up until the point that the orcs start getting dismembered. You might think at this point that the humans we’ve just met are putting up a surprisingly good fight — but no, it turns out there’s a third force here, one which one human describes as “the ones who left” right before he is — presumably — killed. These are the Vangol, who seem to be the primary antagonists for this series.

I say “seem” because the Vangol, too, have their own distinct worldview and society — and hints that something even more unsettling mnay be afoot in this world. Their appearance also lends itself to that sense of unease. While the humans and orcs are recognizable as, well, humans and orcs, Wildgoose’s art gives the Vangol a sensibility that’s harder to pin down. They’re tall, with large pointed ears — but their bodies also seem oddly distorted in places. The best description I can come up with is “feral elves,” which isn’t exactly right, but gives you a general sense of things. Plus: creepy.

In that prologue, it’s worth remembering that a human refers to the Vangol as “the ones who left.” That implies something else: a question of why the Vangol are back, something that comes up a few times in this first volume. Throughout The Hunger and the Dusk, Wilson’s script contains hints of something deeply wrong in this realm — the Vangol on the move is one; there’s also a passing reference to a dwarven civilization that died out. The book also abounds with subtle worldbuilding — including the act that orcs and Vangol once shared a language that has evolved in different ways for each of them.

This comic’s world feels supremely lived-in, and it abounds with small details; Wilson’s script includes a number of allusions to other conflicts happening in other parts of this world. Wildgoose’s art has a welcome kineticism in its action sequences while also giving a large cast of characters distinctive appearances and bearings. For all of the high-concept action, this is a book where many of its subtler dangers come from interpersonal interactions: a misspoken word, a betrayal of trust, a revelation of a lie. The first volume of The Hunger and the Dusk covers a lot of ground; still, I’m left with the feeling that this is just the beginning, with more terror to come.