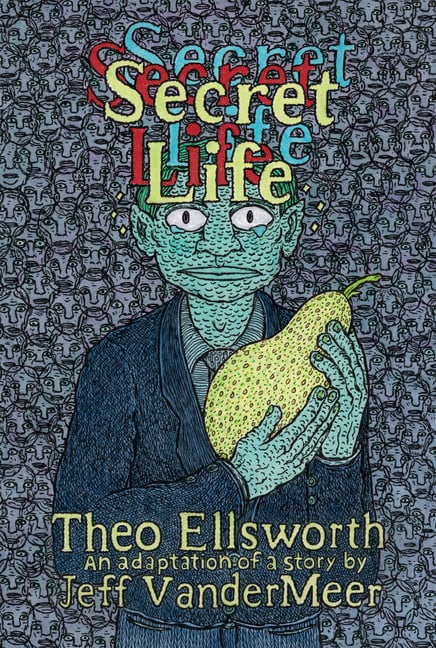

The Branch Office Goes Feral: On “Secret Life”

Exploring Theo Ellsworth's "Secret Life," an adaptation of a Jeff VanderMeer story.

A quick housekeeping note: in an effort to try to get this newsletter back on a more regular schedule, the next few installments — probably four total — are going to be thematically linked. More specifically, they’re going to be about graphic novels adapting works of fiction. First up: Theo Ellsworth’s adaptation of the Jeff VanderMeer short story “Secret Life.”

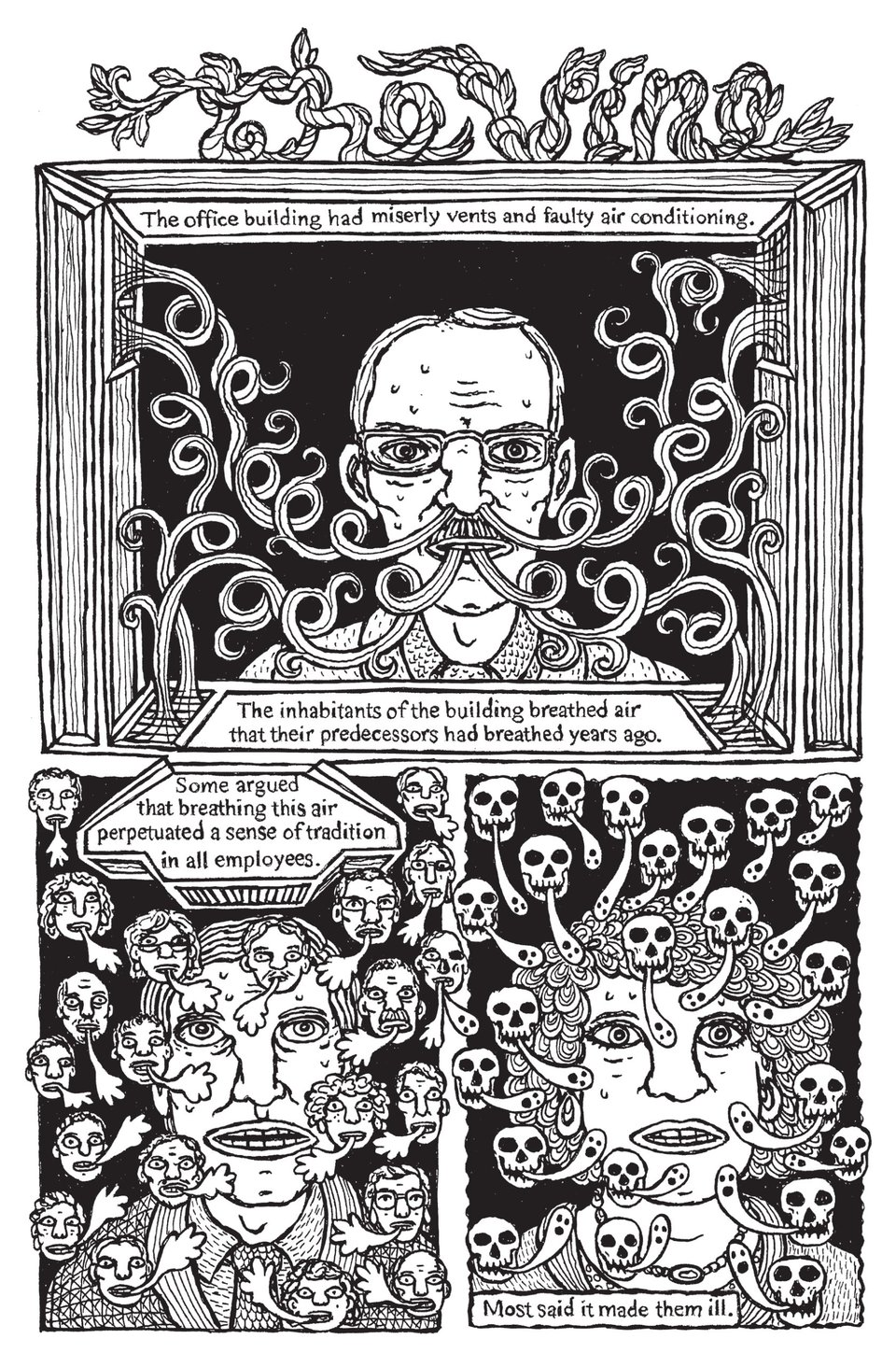

As someone who’s read a lot of Jeff VanderMeer’s fiction — and written about some of it along the way — I feel comfortable saying that his short story “Secret Life” wouldn’t have been my first choice for adaptation into another medium. The story itself is relatively abstract, recounting a series of bizarre occurrences at a surreal office building being slowly taken over by a vine. There’s a bit of Steven Millhauser in its DNA — never a bad thing! — but if you’re looking for a clear-cut story with a protagonist, an antagonist, and a grand conflict…well, this isn’t that.

What it is, however, is a showcase for a lot of big themes: identity, alienation, factionalism, and the adaptability of the natural world among them. Part of the appeal of VanderMeer’s story comes from the contrast between the very sober, restrained narration and the increasingly bizarre goings-on, including the aforementioned vine and subtle warfare between the people employed on various floors. So it’s not all that surprising that Ellsworth makes use of significant amount of VanderMeer’s prose as narration here. That said, it would be inaccurate to describe this as an illustrated version of the story; Ellsworth’s authorial role here comes to the foreground both in how he paces certain scenes and how he’s opted to illustrate specific characters.

One of the ongoing threads in both incarnations of Secret Life is the difference between “night custodians” and “day custodians.” The narration emphasizes them as living and working entirely separately from their counterparts; in Ellsworth’s adaptation, he draws two men, their attire and posture very similar to one another but with significant differences in the specifics: eyes, nose, and build.

Their supervisor is another recurring character in the narrative, and it’s telling to see how Ellsworth adapts the supervisor’s musings on the nature of his workers’ jobs.

“Our faith has to do with honest labor, with the purification of the inanimate. This is how we pray and how we do our jobs. Remember that,” the supervisor says, and Ellsworth illustrates his words traveling into the brain of a sleeping custodian, inspiring a dream of a gravity-defying cleaning of one of the building’s hallways.

VanderMeer’s prose refers to the sleeping custodians as “they smile in their twisted sleep, dancing through the halls with mop and broom.” The narration in Ellsworth’s version leaves that comma hanging; instead, the panels of a custodian making his way down the halls and walls take the place of the closing words of the original sentence.

Ellsworth’s approach to pacing also comes to the foreground in a memorable scene in which a receptionist encounters a strange man clinging to the ceiling in a meeting room. Again, Ellsworth uses some of VanderMeer’s narration but lets the surreal interaction between these two characters play out in silence. The receptionist’s fear and the clinging man’s panic are both expressively rendered in Ellsworth’s art; what it loses of the precision of VanderMeer’s language it gains back in the blend of awkwardness and terror from this fraught interaction.

VanderMeer’s “Secret Life” abounds with a sense of place, and Ellsworth’s adaption emphasizes that element of it, adding a deeply tactile quality. The artwork places the reader into this physical space, making locations like a ventilation system overrun with vines that much stranger to behold. Other details as well, like the not-quite-human look of the mimic featured on the book’s cover, also have a heft to them. “Secret Life” might not be the most obvious selection from VanderMeer’s bibliography to adapt for comics, but Ellsworth has made a memorable graphic novel from it nonetheless.