Subterranean Nightmare Blues: “The Berg”’s Weird Urban Horror

Spend enough time in cities and you’re bound to start wondering about what makes them function. Natural disasters can do an unsettling job of making it clear just how precarious some of the systems are that we depend on — and that’s before getting into some of the more bizarre aspects of 21st century urban life. One of those is the “fatberg,” something that I first read about in The New York Times Magazine and would later see as the subject of a city government prevention campaign.

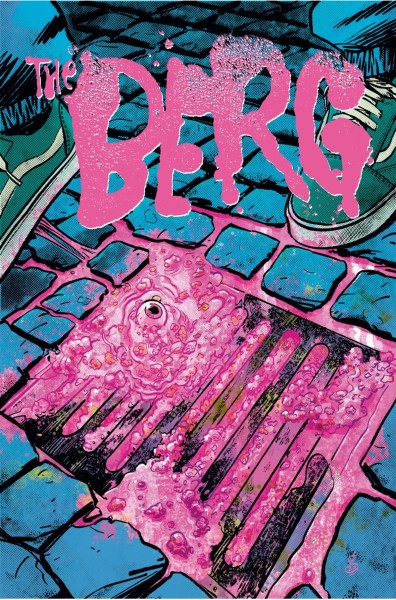

A fatberg is exactly what it sounds like: a mass of waste objects that collects in the sewers, bound together by, well, fat. It’s an unsettling image to begin with, and it was only a matter of time before someone decided to put one at the center of a horror story. Cue the graphic novel The Berg, written by Sarah Peploe and Fraser Campbell, drawn by Gavin Mitchell, lettered by Colin Bell, and with JP Jordan assisting in the coloring. (Full disclosure: I ordered my copy via this book’s Kickstarter campaign.)

The Berg is a short, punchy piece of work with a great concept at its center and some nicely lived-in details to make the fates of some of these characters sting that much more. (Is it a spoiler to say that some of the characters in a horror story meet terrible fates? I don’t think so, but hey.) The first image of the book besides the cover is of a stack of plates being carried out of a dining room, with some garbage — what looks like gristle and bones — on top.

It’s the first indication of what will be the central two themes of this book: waste and labor. Those bones and that gristle have to go somewhere, after all — and the majority of the characters in here are people who’ll have to deal with it in one form or another, whether they’re the restaurant staff or the municipal employees who work with the sewer system all day long.

After a short opening in which the reader sees that all is not well with the garbage of London, The Berg shifts its focus to the aforementioned sanitation workers, three of whom are identified by what they happen to be using their phones for at that moment. They’re dispatched into the field and get the first sign of something being off: the team that was supposed to be on site to meet them is nowhere to be found. The four men descend into the tunnels, and it’s there that things get even more unsettling.

The waste management crew hears and sees strange things in the sewer — some that alter their perceptions of the world, and other things that pick and prod at old tensions within the group. As befits the story’s relatively compact length, some of the character dynamics feel a touch condensed, and become a little more clear on a second reading. Right about here is also when disparate elements of the narrative start to come together: the CCTV feed that should be monitoring the waste management crew picks up static and images from the restaurant where our story began.

Gavin Mitchell’s art has a lot to do here, from distinctive character designs to environments that feel both lived-in and — as the story approaches its climax — horrific and bizarre. The way that the titular beg looks is also notable, from the use of pink to some unearthly lighting effects. The art in The Berg pulls off the trick of looking grotesque, but not so grotesque that a reader might throw down the book in revulsion.

The coloring goes a long way in helping foreground the book’s themes and illustrating its characters’ trajectory from the familiar into the unknown. On the first page, one panel foregrounds the chef precisely arranging a garnish on a plate; the colors leave him grayed out, focusing instead on the kitchen staff in the background. It’s a subtle way of pointing out who the focus will be on in this book: not the solitary genius of myth, but of the workers who band together to get things done. (That’s turning into a theme for this newsletter, and it’s something we’re likely to return to in future installments.

There’s something distinctly pre-apocalyptic about The Berg. Peploe and Campbell’s dialogue creates the sense of a system pushed beyond its limits from the early pages — both the sewer system of London in the specific and humans in cities in the general. Much like John Carpenter’s The Thing — which feels like an influence here — this is a story in which the only thing that can stop an existential threat to humanity is a group of thoroughly flawed individuals, if their own internal tensions don’t tear them apart first.