Jazz Comics: The Uncanny Melodies of “Blue In Green”

I spend more time than is healthy thinking about the way types of art can be translated into other types of art. One of my favorite novels is Robertson Davies’s What’s Bred in the Bone, the protagonist of which begins creating works of art painted in an anachronistic style — and one of the many strengths of that book is the way Davies can evoke a purely visual medium using only his words. But for every case of a What’s Bred in the Bone, there are countless more that stumble.

That’s a somewhat roundabout way to get to the subject of comic books about musicians. On the surface, these two disciplines are as far from one another as prose fiction and visual art. But there are other ways in which these two mediums are closer than expected: for one thing, the use of panels in (at least some) comics create a kind of rhythmic underpinning to them that can evoke the tempo of a given piece of music.

It’ll come as no surprise to say that the three volumes of Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie’s Phonogram were incredibly instructive for me in this matter; the same is true, in a more specific vein, for Jason Hall and Matt Kindt’s Pistolwhip. But those books, Phonogram especially, are dealing largely with more structured music; what happens when you throw jazz into the mix?

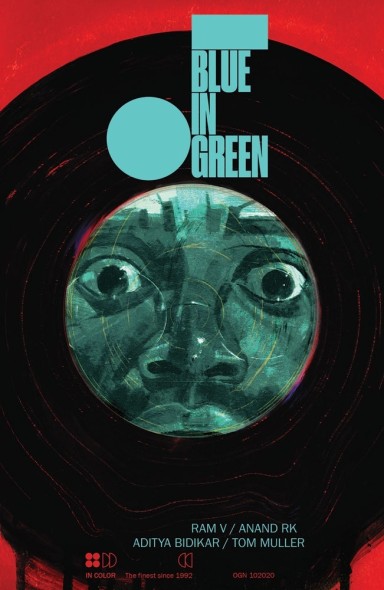

That’s not a rhetorical question. The series Deep Cuts is set in against a backdrop of jazz, and the role of jazz in Dave Chisholm’s Miles Davis and the Search for the Sound should be obvious from the title. (And all of this isn’t too far removed from Harry Smith’s paintings inspired by jazz, either.) And then there’s Blue in Green, a 2020 graphic novel from writer Ram V, artist Anand RK, letterer Aditya Bidikar, and designer Tom Muller. Blue in Green is a story about a lot of things: family secrets, creative obsessions, the weight of history, and demons both metaphorical and literal. But it’s also, at its core, a story about music — and, specifically, jazz.

A couple of things to say from the outset. One: my copy of Blue in Green features a blurb from Phonogram writer Kieron Gillen, which speaks volumes regarding its handling of music in the comics medium. Two: Ram V is a writer with a meticulous sense of pacing. In 2021, Ritesh Babu wrote a fascinating exploration of how the Ram V-penned These Savage Shores used the traditional 9-panel grid to advance the broader themes of the story. Three: Ram V and Anand RK previously worked together on the terrific Grafity’s Wall, which is a very different kind of story from this, and serves a fantastic counterpoint to this one.

The story of Blue in Green finds a man named Erik returning to the house where he grew up in the wake of his mother’s death. Erik himself is a frustrated musician who makes his living as a teacher and, even from the earliest pages, it’s clear that there are certain things he won’t discuss with anyone - whether they’re artistic frustrations or familial trauma. (Or both.) It’s when he returns home that he reunites with his estranged sister Dinah and an old flame named Vera. And it’s through the discovery of a photograph in his late mother’s home that he begins seeking out a jazz musician. A flashback, set decades earlier, offers a sense that there’s something uncanny afoot here.

It’s not much of a spoiler to say that there are supernatural elements here, though they also have an especially metaphorical element to them. “The dead don’t become ghosts until we start lookin’ for them,” Ollie, an older man who’s known Erik for much of his life, tells him at one point. This is the sort of book in which the ghosts and demons are metaphorical, in some ways — but they’re also tactile presences throughout the story, capable of no small amount of damage. (This would make for an excellent cross-disciplinary double bill with Hari Kunzru’s novel White Tears.)

Among the most unsettling aspects of Blue in Green is the notion of creative expression as something that’s both transcendental and terrifying. Art can be liberating; it can also be something that takes you to troubling places and changes you in unsettling ways. The fact that Ram V’s script doesn’t shy away from this aspect of the story is to its credit; it’s also a good reminder that the best kind of horror is the kind that isn’t easily shaken off.

As befits a book about jazz, the ways in which the creative team get their own moments to shine seems especially apropos. There’s a painted quality to RK’s art which veers from photorealistic to impressionistic and back again. Consider the way Erik’s face is perpetually blurred, which hints at his own uncertainty in life and art. Later in the book, Erik converses with an older woman with dementia; unlike him, her face is captured in precise detail. But there are also ways in which the visual presentation of the book comes together in unorthodox ways. In one panel later in the book, Erik’s narration caption is positioned to cover another man’s eyes. The words? “In him I recognized myself. In his bloodied face…something intimately familiar.”

Bidikar’s lettering technique gets a workout here; dialogue and narration have distinctive looks, and there are moments where some of the text is layered directly on an image, creating a sense of illustrated prose. For other scenes, the story is told with a more traditional panel-based system, and it isn’t hard to see this as a comics medium version of a jazz quartet playing a melody and periodically spiraling off into improvisations along a given theme, then returning back from there.

That improvisational and referential quality also feels present here in subtler ways. At one point, Erik finds a group of photographs strewn on the ground in his mother’s house. It’s a minor detail, but it also echoes the way RK arranges the panels on one of the book’s more impressionistic sequences later on in the book. It’s not clear if that was intentional, but it certainly feels like the way a musician might take a few bars of something played earlier in a piece and turn it into something transcendent later on.

There’s a lot happening in Blue in Green that I haven’t touched on here, from Erik’s unsettling family history to a subplot about an old acquaintance of his making moves in the New York City music world. And the methods by which RK moves from style to style — including a markedly different visual language for some of the flashbacks — is equally virtuosic. The uncanny elements of Blue in Green’s story might make you shudder and turn your head away, but the command of craft on display here will leave you lingering, wondering just how these talented collaborators pulled it all off.