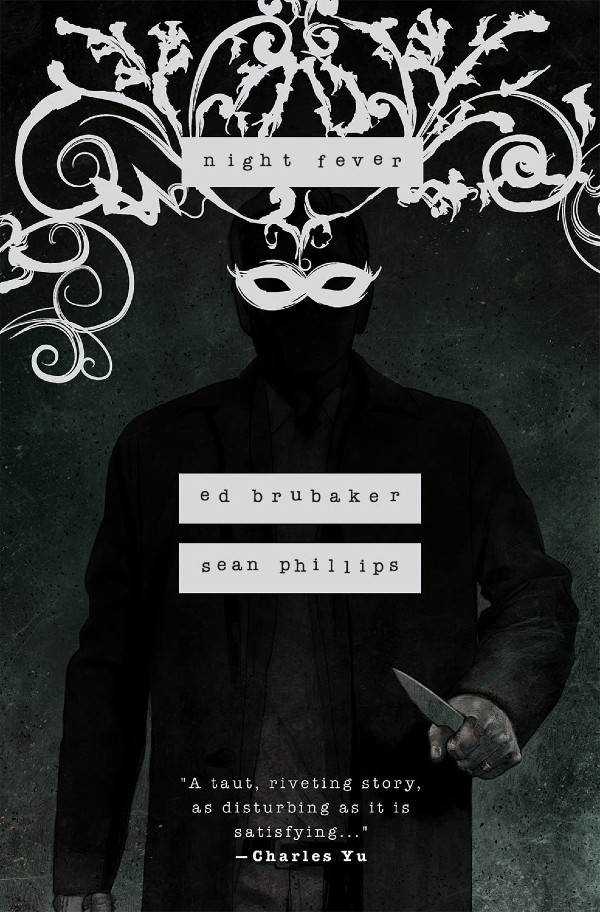

Gateway Drugs: How I Caught “Night Fever”

Can a graphic novel get you to watch the better part of 13 hours of television? In my case, yes. Those two things are not as disparate as they might seem; the graphic novel in question is Night Fever, from the long-running team of Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips. The television in question is Too Old to Die Young, Brubaker’s collaboration with filmmaker Nicholas Winding Refn. And while the two are wildly disparate for a number of reasons, this was where a lot of things fell into place for me with respect to Too Old to Die Young - all the while offering a new vantage point on Brubaker and Phillips’s impressive bibliography.

Night Fever begins with a man far from home, so it’s fitting. It’s 1978; Jonathan Webb is 45 and works in publishing. Specifically, he works in foreign sales; he’s in Europe for a book fair, and he’s having trouble sleeping, haunted both by a traditional-seeming midlife crisis and a less-traditional moment of existential panic owing from him having discovered an unnerving similarity between a detail in a novel he’s reading and a memory from his past.

“I hadn’t slept for three nights. So who knows why I was doing anything?” he thinks at one point. The context: Jonathan is out searching for sleeping pills and spots a well-dressed couple in masks en route somewhere. He decides to follow them; needless to say, hilarity does not ensue. He arrives at an exclusive gathering, adopts the identity of another guest (a man known as Griffin) and eventually encounters Rainer, a compelling and amoral figure who pulls him deeper into a bizarre underworld.

At this point, it’s safe to say that Phillips can draw pretty much anything, and the scenes of Jonathan-as-Griffin walking through something that’s equal parts gambling den, sex party, and high-society meet-and-greet allow him to show off his range (and also let colorist Jacob Phillips add to the surreal tone). There are a few deeply unsettling touches here, including a pair of animatronic figures that resemble skinned cyborgs. Precisely what they’re doing there is never stated, but it adds another layer of mystery to the proceedings.

The names Rainer and Griffin are both fraught with meaning as well. Though the former doesn’t resemble the real-life filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the two share both a penchant for provocation and a kind of omnipresence. As for Griffin, readers with a penchant for pulp fiction might note that the metaphorically invisible man whose identity Jonathan adopts shares a name with the literal protagonist of H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man.

Just as the title character of Wells’s novel becomes increasingly drunk on power, so too does Jonathan embrace the freedom of his identity as Griffin — going from doting husband and father to someone willing to engage in brutal violence and casual infidelity. And there are also signs throughout that Jonathan himself isn’t always the most reliable of narrators, including his sleep deprivation early on and his consumption of alcohol and stronger substances later in the book. It’s a fascinating juxtaposition: one of the more buttoned-down protagonists in Brubaker’s bibliography navigating their way through a landscape that’s increasingly hard to pin down.

It’s worth mentioning here that Brubaker is also the first creator who I’ve written about twice in this newsletter; early on, I wrote about the first volume of Friday, his collaboration with artist Marcos Martin. Part of the pleasure of reading that book is seeing what kind of story is actually being told; what begins as the story of a former kid detective returning to her hometown gradually morphs into something stranger. That push towards a liminal space between genres is also present here.

Most of Brubaker and Phillips’s collaborations have fallen soundly into one genre or another — Criminal and Reckless are crime fiction; Fatale is a slow-burning tale of horror. With Night Fever, though, it’s harder to say, The primary reference points don’t feel like comics as much as they do films — as befitting the period setting, I find myself thinking of movies like The American Friend and Bad Timing, stories told with an elliptical logic in which mysteries and violence feel close at hand. (The cinematic references don’t stop there; a bar called Cercle Rouge plays a significant role late in the story.)

Finishing this book — devouring it, even — is what led me to finish Too Old to Die Young: to search for more of that cinematic quality in Brubaker’s work, albeit in a different medium. What I found was something not terribly close to this but not far from it, either. (At The Ringer, both Micah Peters and Miles Surrey wrote engaging takes on the series.) I have no idea if Brubaker and Phillips will ever do a book like this again, but I’m glad they made this one.