DC Punk Mysteries: Reading “A Ghost Arm Made of Angry Ghosts”

Punk rock, superpowers, and subtly altered histories converge in this new comic.

By way of introduction: I hadn’t been planning to file another email this week, and then I ended up browsing a comic shop’s Instagram feed, and things escalated from there. Specifically, this was the feed of The Geekery, a terrific store situated not far from where I grew up in central Jersey. I was out there this week visiting family and I’d been meaning to stop by to pick up the third volume of What's The Furthest Place From Here?. Was there anything else I should keep an eye out for? Hence my foray into social media.

It was there that I first learned of the existence of a new comic called A Ghost Arm Made of Angry Ghosts, which came recommended by the shop. First and foremost: that’s a fantastic title and a great way to get my attention. Second: The Geekery’s post about it mentioned that it tied in to the DC punk scene of the 1990s, which is pretty much catnip for me. Third: A Ghost Arm Made of Angry Ghosts.

From that description, I found myself expecting something like Dan Watters and Caspar Wijngaard’s Home Sick Pilots. What I got reminded me a bit more of something slightly different — if Christopher Priest and Farel Dalrymple collaborated, maybe? To tie things back in with What’s the Furthest Place From Here?, that book’s Matthew Rosenberg has an absolutely spot-on description of it that shows up here.

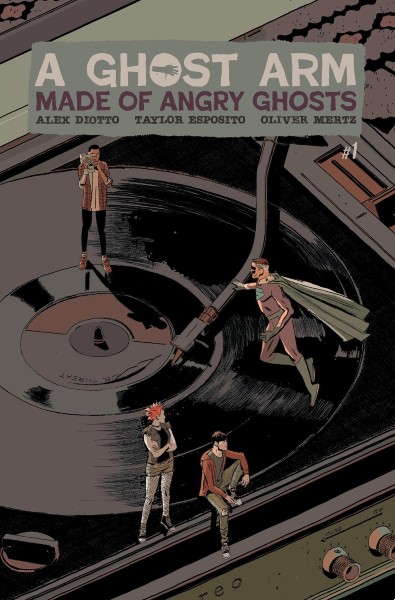

What I have in front of me is the first issue, though it’s essentially a graphic novella all its own. Oliver Mertz wrote it, Alex Diotto is responsible for the art, and Taylor Esposito lettered it. The first thing to note about this book is that there are two prologues, for all intents and purposes. The first one provides some backstory for this book’s version of history, with a reference to a ”publicly recognized person with extraordinary abilities” documented in 1913 — but what we get is less about that and more of an extended epistemic digression on the history and nature of the sandwich. And that sets the tone in a great way, both letting the reader know that this book is going to take something of an irreverent tone and that its very narration is going to go beyond names, dates, and locations.

Prologue number two introduces us to Ari Ackerman in 1988, when he’s six years old. Young Ari discovers that his next-door neighbor is the superhero Gamut; he also sees something that seems like a trick of the light but plays out a little differently on a second reading. The bulk of the book is set 10 years later; Ari and his friend Maya Meng are meeting up to go to a punk show. And clearly this is a book made by people who know their musical history — the presence of Monorchid and pageninetynine posters in Ari’s bedroom is a testament to that.

That aspect of the book’s history feels eminently recognizable. In other ways, Mertz and Diotto make it clear that this 1998 is a very different from the one we remember. Countless people have uncanny abilities — a friend of Maya’s mother can grow to a gigantic size, while a woman named Marlowe has the power to control the local weather. Not every ability is useful, though: Ari’s father appears to be in a cycle of dying and returning to life every night, a regular enough occurrence that father and son have scheduled their television routines around it.

This book is divided into sections, with an all-black panel with text signifying the existence of a new chapter. (Hence the Priest comparison earlier.) It’s also here that the book’s narration fills in some more details on the alternate history we’re reading — though it’s interesting that the pop culture remains largely unchanged, based on the fact that characters discuss the film Groundhog Day and the Seinfeld finale. It’s especially interesting to read this in close proximity to Kieron Gillen and the aforementioned Caspar Wijngaard’s The Power Fantasy, with which it shares some similar qualities — a 90s setting, a unique take on superpowers — while utilizing them in radically different ways.

Mertz’s script abounds with lived-in moments. The conversations between Ari and Maya, and between Ari and his father, feel idiosyncratic and specific; the two friends have a penchant for riddles and word games, while Ari’s father can be a bit passive-aggressive about his condition. And Maya has an impassioned speech about dancing (or the lack of it) at punk shows that read, to my aging punk eyes, like a version of many conversations I’d had in the 90s.

There’s also a lot of groundwork established here for plotlines that will likely play out over future installments, including a pair of mysterious deaths and some mysteries around Ari’s mother. But this also feels like a solid piece of storytelling all its own; I get something of a Guy Davis vibe from Diotto’s art, which keeps things rooted in a sense of the real even as stranger occurrences pop up on the fringes.

As a reader who can recognize a Monorchid poster on the protagonist’s wall and thinks it’s pretty cool that it’s there, I understand that I’m probably in this comic’s target demographic. (And if we can get a breakfast violence subplot in here, I’ll do a metaphorical backflip out of sheer joy.) That said, I’m also very aware that this combination of 90s punk, the DC metro area, and superheroes doesn’t play out in any way that I might have expected. There’s a lot of weirdness about punk rock, and there’s a lot of weirdness about superpowers. A Ghost Arm Made Of Angry Ghosts taps into that weirdness and turns it all the way up — and it’s the better for it.