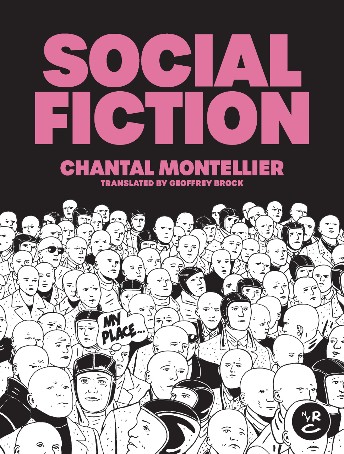

A Lost Dystopia Is Found: On “Social Fiction”

The best thing about dystopian narratives is the same thing as the worst thing about dystopian narratives, which is to say: they tend to stay relevant for far too long. A perfect case in point is Social Fiction, a collection of three comics by writer-artist Chantal Montellier, here translated by Geoffrey Brock. These were first published in the 1970s, and yet they haven’t stopped being relevant in 2023. Quite the contrary, in fact.

Some of that can be chalked up to Montellier’s areas of interest. These are stories about the challenges of creating a new society under arduous circumstances, about dealing with a repressive and authoritarian infrastructure, and the alienation that can be born from encounters with different forms of technology. Certain dystopian tropes are evergreen; there’s a reason why people continue to cite 1984 and The Dispossessed long after they were first published. But there’s also the matter of some of the specific nightmares that Montellier summons up on the page, which have an especially haunting resonance in the U.S. circa now.

As Brock explains in this book’s introduction, Montellier’s 1970s work appeared in translation in places like Heavy Metal and National Lampoon — though in one case, her work was marred by what Brock dubs “a radical ‘localization’ experiment” which seemed designed to evoke an alienated near-future slang but which largely comes off as unreadable. (Imagine Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker, but with the linguistic stylization cranked up way past 11.)

That checkered publication history might help explain why these stories haven’t found a wide Anglophone readership in the years since they were first published. The clean linework of Montellier’s art occasionally recalls Jaime Hernandez’s Maggie and Hopey stories, and it’s fair to say that both writer/artists also share a fondness for DIY spaces and protagonists who dwell on the fringes of society.

The work in Social Fiction is more overtly science fictional, though — there’s a bit of J.G. Ballard in the way that Montellier places a vibrant protagonist against an uncaring and even antiseptic world. This is most pronounced in “Wonder City,” the story that opens the book, which tells the story of a furtive romance between a government worker and a musician. Both live in a world where reproduction is strictly regimented by the state, as are other elements of daily life — two characters discuss loyalty oaths in the opening pages. (“Did you sign their famous ‘loyalty oath’?” “Yes, or else I’d be fired… How about you?”)

The everpresent figure in this society is a supercomputer called Nimbus, represented with the face of an eccentric and slightly lascivious older man; think Big Brother by way of Benny Hill. If “Wonder City” concerns itself with societal overreach, then “1996,” which closes out this volume, reckons with runaway consumerism and societal racism. The society depicted in “1996” is one where retail shops, art installations, and graveyards have somehow merged into one sprawling location.

There’s more than a little dream logic to both this story and its predecessor, “Shelter.” But the protagonist of “1996,” a Puerto Rican man named Alfredo Garcia who’s simply trying to carry out the most basic tasks and is stymied by the racism of the society around him, must contend with plenty of horrors that have nothing dreamlike about them.

Dreams and reality also blend in “Shelter,” about a group of people who are shopping in an underground mall at a time when they become cut off from the rest of the world. They embark on what one character dubs “a living experience of an entirely new kind.” The way in which this new society gradually becomes authoritarian, with its norms enforced in increasingly brutal ways, has its own terrifying logic.

One vignette establishes this in especially unsettling terms. Theresa, one of the people caught up in this society, works at the mall’s bookstore, which has become a library. She notices that the men in charge of security have begun checking out books and not returning them. “[N]one of these guys particularly looks or acts like an intellectual,” she says later, “yet they’re only checking out books on philosophy and politics!” This behavior is not too far removed from a real-life news story published the same week as this edition of Social Fiction.

Social Fiction is a frequently chilling read, in the way the best dystopias are. But this haunting work is well worth looking into — both for the ways in which it brings overlooked work back into the spotlight and for the ways in which Montellier’s stories still feel very relevant in 2023.

I don’t get to write about comics all that frequently on a freelance basis — one of the reasons this newsletter exists — but I did discuss Léa Murawiec’s graphic novel The Great Beyond at Words Without Borders. And at Vol. 1 Brooklyn, I wrote about the new anthology The Devil’s Cut.