Rubber Soul at 60: The Beatles Against The Wall

It was October 12, 1965, and the Beatles were exhausted.

How could they not be? They were nearing the end of the most chaotic year any band has ever experienced, the only competition being… themselves in 1964, the year the Beatles broke through internationally. 1965 was largely the same, more touring, more television appearances, another movie. So many more days of being hurried from hotel room to airport to hotel room, being the most famous men in the world, living largely isolated and claustrophobic lives at a breakneck pace. The albums they managed to record during this period, A Hard Day’s Night and Beatles For Sale in 1964, and Help! in 1965, were steps forward for the group, but in subtle ways, and are largely grouped alongside their first two records as being the Beatlemania-Era albums. Pop songs with simple lyrical sentiment, energetic instrumentals, and gorgeous harmonies that made their young fans go bonkers.

For their part, the Beatles had gotten very good at rolling with the punches and embracing this chaotic lifestyle as the most sought-after people on the planet. But the strain of this way of life would rear its ugly head at certain points, and it affected how they worked and what their music was about. Most famously, “Help!”, the title track to both their fifth album and second feature film, was understood as a cry for help from bandleader John, with the band repeatedly shouting “HELP!” which must’ve been a cathartic intro to perform. Before this, John Lennon and Paul McCartney began running out of songs near the end of 1964, and after all they went through that year, they still needed an album out in time for the holidays. This led to what is likely the least highly regarded Beatles album, Beatles For Sale, consisting of six covers and eight originals, following up an album that consisted entirely of Lennon-McCartney tracks. Those originals, consisting of songs such as “No Reply”, “I’m A Loser”, “I’ll Follow The Sun” and “I Don’t Want To Spoil The Party”, are some of the best the band had written up to that point and did showcase an evolution in their songwriting. John’s songs in particular revealed a more melancholic, reflective and self-loathing side of his lyricism that had only been hinted at on their previous albums. Unfortunately, the group had very little time to work on Beatles For Sale before it was rushed onto store shelves for the 1964 holiday season, and stuffing the album with good but standard cover tracks dragged the project down overall.

It was October 12, 1965, and the Beatles must have been feeling deja vu.

As the holiday season approached yet again, their label EMI was expecting another album in time for the holiday sales surge. This meant that, once again, the band had precious little time to record their second album in 12 months, coming off of an incredibly hectic year. Under different circumstances, this could have been another Beatles For Sale, an album where artistic growth could be found between the lines as the group matured as songwriters and musicians, but was bogged down by lackluster covers, tight deadlines and the band simply being spent. Fortunately, unlike the year prior, the Beatles were afforded a month of uninterrupted time in the studio. For at least a few special weeks, John, Paul, George and Ringo were able to hone their skills, showcase their growth from the past year, and focus almost solely on completing this album.

Even with the free schedule, this would not be an easy task. Any musician knows that making an entire album in just over a month is incredibly challenging, and the stakes are raised extraordinarily if you’re the biggest band in the world and rapidly approaching a creative peak. It’s a position the Beatles found themselves in numerous times. During the famous Get Back sessions in 1969, when the group was in urgent need of material, John quipped that “When I’m up against the wall, you’ll find I’m at my best.” If Rubber Soul is any indication, he was correct.

The Rubber Soul sessions began with two John compositions, the defacto bandleader in the middle of what would prove to be one of his most prolific and successful periods as a songwriter. The songs worked on this day, “Run For Your Life” and “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown),” one a straightforward rocker and one a moody ballad, seemed to represent the past and future for the band. The former, one of the many Beatles songs Lennon would deride in interviews after the band broke up, was a dark take on the 1950s classic “Baby Let’s Play House”, a notably bitter and vengeful song in their catalogue that highlighted arguably John’s worst quality: his violent jealousy. It’s something Lennon dealt with throughout his life, the source of much of the modern criticism directed at him today, and an issue he particularly struggled with in the early years of the Beatles, when the rockabilly influence of songs like “Baby Let’s Play House” was at its strongest.

I consider this song a moment on Rubber Soul that looks backward, in both its lyrical matter (not to say John WASN’T still dealing with his jealousy issues, it was a lifelong skeleton in his closet) and in its composition. While the subject matter may be among the darkest in the whole Beatles catalogue, the instrumentation is jaunty and energetic, particularly in George’s rollicking guitar work. It feels as informed by the rock music of 1960 as it is by anything that was happening 5 years later, and that feels appropriate for a song sitting in a perspective its writer would’ve been very familiar with at that time. Its place as the album closer for what would become a largely pleasant and introspective work feels less appropriate, and I used to hold that against the track, but despite its lyrical content, I have to admit that the song is a total fucking jam. On a musical level, it ends the album in a fun and familiar place for the band, showing just how much the group’s musicality and chemistry has improved in the time they’ve been together.

The day’s second song, “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown),” is the opposite. The track, which would be reworked and rerecorded on October 21st, is often cited as one of the major turning points of the Beatles’ career. This song, particularly for John and George, very much looks forward. The acoustic ballad chronicles an affair John was having at the time. This was, infamously, a fact of life for John and the rest of the band during their time as Beatles, but it’s not a very-glamorous sounding affair. John sounds almost apathetic recounting the events, which mostly consist of the unnamed woman showing him her place made of wood of a Scandinavian variety, talking, fucking, and John waking up in the tub to her room being empty. (The song really ends with the line “So I lit a fire/Isn’t it good?/Norwegian wood” which Paul says in Barry Miles’ Many Years From Now is the narrator actually setting the house on fire, though I personally prefer to think of it less dramatically, like lighting a fireplace.) No one comes out of this looking particularly good. With most Lennon-McCartney compositions, the exact authorship is murky, though both agree that John was the primary writer. If I had to guess, Paul’s influence can mostly be heard in the storytelling aspect of the song, as that was more his strength.

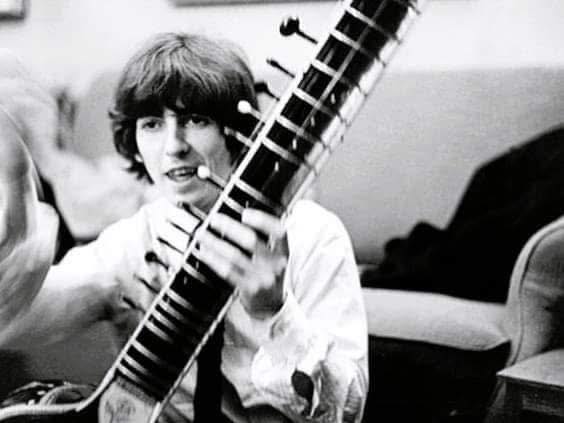

The maturity and complexity shown in “Norwegian Wood” is worth highlighting, as it sits in stark contrast from the more black and white love songs that are found in the band’s earlier work. But where it really gets its notoriety is from one element in the composition, this being one of the first western pop singles to incorporate a sitar. While filming Help!, George started developing an interest in Indian classical music, which uses instruments not commonly found in western music, most famously the sitar. As The Beatles Bible (a website run by Beatle die-hards that chronicles a day by day timeline of the Beatles’ careers alongside in-depth articles on each song, and an invaluable resource for Beatle fans, and for researching for this article) notes, bands like The Yardbirds and The Kinks were already experimenting with tones found in Indian classical like droning; the Yardbirds even use a sitar in their landmark single “Heart Full O’ Soul.” But George’s use of the instrument reveals one of the most important truths about the Beatles: they weren’t originators, but popularisers, always just ahead of the rest of the mainstream.

George was still very new to the sitar when recording “Norwegian Wood” and didn’t play it with the proper technique he would soon study. Instead, the sitar is essentially used as an exotic-sounding guitar on the track. It’s not used for its droning qualities, but instead played very melodically, serving the lead guitar role of the composition. Although only one take was recorded on the 12th, the band was afforded hours of rehearsal time in order to nail the composition. This would become a regular occurrence during the Rubber Soul sessions, rehearsing for hours at a time, so that the band would be more familiar with their material than ever when it came to the actual takes. When the band returned to this song a week later, their familiarity with it allowed them the space to experiment with the sitar, with takes ranging from no sitar at all to the instrument dominating the track. The final take landed somewhere in the middle, adding a unique texture to this acoustic ballad while not taking attention away from the somber, cryptic lyricism on display.

On the second day of the sessions, October 13th, the album opener “Drive My Car” was recorded. Rubber Soul is most commonly seen today as a landmark in folk rock, taking obvious inspiration from acts like The Byrds and Bob Dylan. This can be seen in “Norwegian Wood,” with its acoustic-heavy instrumentation and its ambiguous lyrics that took clear inspiration from the preeminent songwriter of 1965. However this inspiration wasn’t top of mind for the group when they were conceiving of the album. The biggest influence on Rubber Soul is something so obvious it’s right in the title: soul.

The Beatles owe much of their success to the American soul and R&B that was being produced in the 1950s and early 1960s. A large portion of their covers are of songs in this vein, including Motown singles like “You’ve Really Got A Hold On Me”, “Please Mister Postman” and “Money (That’s What I Want)”, all featured on their With The Beatles album. Although the Beatles are mainly discussed alongside other white British groups that gained popularity in their wake, this Motown influence never went away. Bassist James Jamerson likely had a bigger role than anyone else in the evolution of Paul’s bass playing. Jamerson was a very melodic player, infusing his basslines with “Sixteenth notes, quarter note triplets, open string techniques, dissonant non-harmonic pitches and syncopations off the sixteenth,” (Bangs et al, Let It Bleed, 32). Now, I am not a musician, and I don’t fully understand what all of those terms mean, but what I do know is that Paul’s playing got much more complex shortly after Jamerson’s did. What were once simple backbones to pop songs started to draw attention to themselves, filling out the low ends with much more tuneful bass playing, more reminiscent of Paul’s skills as a masterful melody writer.

The sound of R&B can be heard all over “Drive My Car,” not just in the Jamerson-esque bassline. The most prominent influence actually comes from an artist on the Stax label, Otis Redding, whose future smash “Respect” was specifically cited by George when the band was working out the composition. Redding can be heard all throughout this track, from the intertwining guitar and bass, to the jaunty piano, to the shrieking lead vocals from Paul and John. It’s one of the band’s most exciting and effective openers of their whole discography, and it’s pure plastic soul. It, alongside “Norwegian Wood” as a follow-up, casts a long shadow over the rest of the album, showcasing the R&B and singer-songwriter stylings that combine to give Rubber Soul its identity.

Although the soul influence is what I find most important about “Drive My Car,” the recording session for this track also foreshadowed the rest of the Beatles’ career in a small way. According to Mark Lewisohn’s documentation in The Complete Beatles’ Recording Sessions (the most comprehensive documentation of their time in the studio, and where the session information in this piece can be sourced to), the “Drive My Car” session lasted from 7 PM to 12:15 AM, making it the first Beatles session to end after midnight. As the group became studio wizards over the course of the next few years, this would become very common, affecting the way the group worked and allowing them the time and space to craft the more experimental and layered compositions that would redefine their image on albums like Sgt. Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour. Even if it was for a straightforward soul cut, “Drive My Car” was the beginning of a new era in this way.

October 16th saw work done on two tracks, the future single “Day Tripper” and George’s first composition of the album, “If I Needed Someone.” The creative process behind “Tripper” highlights two running themes found throughout the Rubber Soul sessions. In a 1969 interview, John claimed that he wrote the song “under complete pressure,” a reminder that the band was still backed against a wall, with EMI expecting both an LP and a single in time for the holidays. “Day Tripper” was one of the most straightforward rock songs the band recorded in late 1965, with punchy vocals from Paul and trademark Beatle harmonies, all anchored by one of the most recognizable riffs of any Beatles track; musically, it was a no-brainer single choice.

The other theme “Day Tripper” highlights is what makes it something of an unconventional 45 for a band that was still largely seen as being for teenyboppers. The Beatles used drugs! And were around other people who used drugs! And wrote about it! Scandal! “Day Tripper” is specifically about a woman who likes to partake in the burgeoning drug scene of the mid-1960s, but won’t fully commit to it. As Paul says in Barry Miles’ Many Years From Now, Lennon and McCartney saw themselves as “full time trippers, fully committed drivers, while she was just a day tripper,” someone who had one foot in the counterculture and one foot in mainstream society, not feeling the full freedoms of these drugs. The Beatles, you could say, were full time trippers, and their use of drugs especially around this time is very well documented. I’d highly recommend the book Riding So High by Joe Goodden if you want a more complete history of their drug use, but the substances most relevant to their creative process during this period were LSD, which all four Beatles had used at least one by the end of 1965, and marijuana, which had become a heavy influence on their writing by this time. “Day Tripper” may not be their most explicit drug reference in their music, but for 1965, releasing a commercial single with this many subtextual references to drug culture was a bold move for the Beatles, showing how the pressure to meet demands for new music was pushing them forward creatively as their lives were changing.

With one half of their next single already knocked out, the group spent the rest of the night working on George Harrison’s first of two contributions to Rubber Soul. At the time of recording, George had just three songwriting credits on Beatle projects – “Don’t Bother Me” on With The Beatles, and “I Need You” and “You Like Me Too Much” on Help!. Despite his lack of representation (an inevitable byproduct of being bandmates with fucking Lennon-McCartney), George was clearly a burgeoning writer with a unique perspective and would provide two tracks that are integral to Rubber Soul’s identity. “If I Needed Someone” is, or at least should be, one of the first songs people point to when arguing that Rubber Soul is primarily a folk-rock album. If any one act defines folk rock, it’s The Byrds, and if any one instrument defines folk rock, it’s the Rickenbacker 12-string, and the effectiveness of this track is indebted to both. George had been using the Rickenbacker since at least “A Hard Day’s Night,” but Byrds leader Roger McGuinn would make the instrument its own and helped define the LA sound of the 1960s, another American music scene that proved incredibly influential on the Beatles. According to the site BeatleBooks, George wrote this song with the Byrds in mind, even sending McGuinn a tape of the song after it was completed, since the similarities were so obvious. With this song, George was paying tribute to one of the strongest Beatles disciples on the other side of the Atlantic and giving the new album its folk-rockiest number yet.

With the clock ticking towards midnight, only the rhythm track for “If I Needed Someone” was recorded on the 16th. The group nailed it in one take; a testament to their discipline in the studio and the effectiveness of their rehearsals. The song was finished two days later, on October 18th, with the band adding vocals, tambourine and guitar overdubs to complete the recording. With four album tracks and one side of a single complete, and plenty of time left in the day, their efficiency in the studio was paying off; they were quickly progressing on the new album just one week after sessions began. Work quickly began on another John-penned track, one that would prove to be the most enduring song on the album and, arguably, the greatest song by the Beatles.

I have gone through many different picks for my favorite Beatles song. There’s the melancholy baroque pop of “Eleanor Rigby,” the acoustic pop perfection of “Here Comes The Sun,” and the experimental psychedelic freakout of “Tomorrow Never Knows,” to name just a few. As I type this, in late 2025, I think the best song in the entire Beatles catalogue is the song they began recording on October 18, 1965, “In My Life.”

A quick aside before getting back into the timeline, but I think this anecdote is a good example of the power “In My Life” can have over people. As a baby Beatles fan, most of my knowledge of their music came from the 1 compilation album. That was the Beatles CD that was always in my parents’ car, and those were the first Beatles songs I memorized and heard most often in my early childhood. “In My Life” was not a single, and thus didn’t go to #1 in the US or UK, meaning I never heard the song until actually listening to the Rubber Soul album. It felt like a rarity to me, and even as a very young child, probably six years old, I knew what I was hearing was special. The gentle guitar riff, the introspective lyrics, the quiet harmonies that carry throughout the track, that piano solo!! This song was making me reflect, both on what I imagined John’s life was like, as well as my own. And mind you, I was six! I was a baby! I hadn’t lived at all yet!! That’s the power of this song, it makes you take stock of what you have and what you’ve done, in a way no other Beatles song does, and even decades later, that experience of hearing this song and knowing how special it was has stuck with me and really informed my relationship with it to this day.

John Lennon, an infamously self-critical person, agreed, consistently holding up “In My Life” as one of his best ever compositions. He had every right to be proud of it, he worked on the song for over a year and it represented a major evolution in his songwriting. For the first time, the most self-conscious writer in the Beatles was looking back on his life and using it as direct inspiration for his music. Prompted by critic Kenneth Allsop when discussing Lennon’s 1964 book In His Own Write, John began writing a song detailing the sights and sounds of Liverpool, a concept that would be perfected by Paul on “Penny Lane.” Unsatisfied with the results, calling it “the most boring sort of ‘What I Did On My Holiday Bus Trip’ song,” John reworked the lyrics into something less specific, crafting them into a universally relatable song about looking back on your hometown and your friends, and the memories those people and places hold. These lyrics are some of the best that pop music has to offer, conjuring up a reflective mood so strongly and with such simple wording that they make even a six year old feel nostalgic! The song takes a turn into love song territory in the second verse, with John proclaiming that, as powerful as these memories are, they pale in comparison to how he feels about you. While I think this song is at its best when it’s a wistful look back in time, it also contains some of the most romantic lyrics John ever wrote, and the way these two halves of the song connect back to each other is expertly done.

“In My Life” is one of the few songs where John and Paul’s recollections on who contributed what differs greatly. John claims that Paul’s contributions were mostly to the middle eight, and is very proud of the melody he wrote for the track, Paul claims that he’s responsible for the main melody, as well as the guitar riff that bookends the song. While I’m tempted to believe Paul, seeing as he’s maybe the greatest melodic writer in pop history, John could conjure up a fantastic melody in his own right when he wanted to, and “In My Life” was a song he clearly cared about deeply. We’ll never definitively know who wrote what, so my take on the matter is that this song was primarily John’s, and contains contributions, in some form, from one of the people who made his time in Liverpool so meaningful.

The Beatles, operating like a well-oiled machine in the studio by this point, were able to knock out 90% of their masterpiece in just this afternoon session. By the end of the session, the entire track was completed, save for a solo that would be played by producer, correct answer for “who was the fifth Beatle,” and all around cool guy, George Martin. It’s been said countless times already, but Martin was really the best possible producer for this band. His authoritative yet gentle presence in the studio, combined with his past experience as a producer for comedy albums, made him the perfect overseer of the Beatles’ studio time, a guiding presence that was always willing to experiment alongside the boys. On October 22nd, Martin planned to dub an organ solo onto “In My Life” to fill out the track. After deciding it would sound better on piano, Martin realized how challenging it was to nail the solo in the time afforded to him in the song. His workaround was to play the tapes at half speed and perform the solo slower. When running at normal speed, the solo not only fit perfectly, but sounded more like a harpsichord than a piano, giving an added layer of elegance to the completed song. Just like that, my favorite Beatles song was finished.

After taking the 19th to unsuccessfully work on their annual Christmas fan club single (George wasn’t even in the studio!), the four reconvened on the 20th to work on the other half of their next single, “We Can Work It Out.” The track, one of the most highly cited when discussing the differences between Lennon and McCartney as songwriters, highlights one of the more underdiscussed throughlines of Rubber Soul: the rocky relationship between Paul and his then-girlfriend Jane Asher. Asher, a successful actress in her own right and Paul’s (PRIMARY) girlfriend from 1963 to 1968, was one of Paul’s major muses during his time as a Beatle, and few albums showcase this more than Rubber Soul. At this point in the sessions we’ve seen very few songs penned primarily by Paul, but “We Can Work It Out” would prove to be the first of multiple songs about his relationship troubles with Jane.

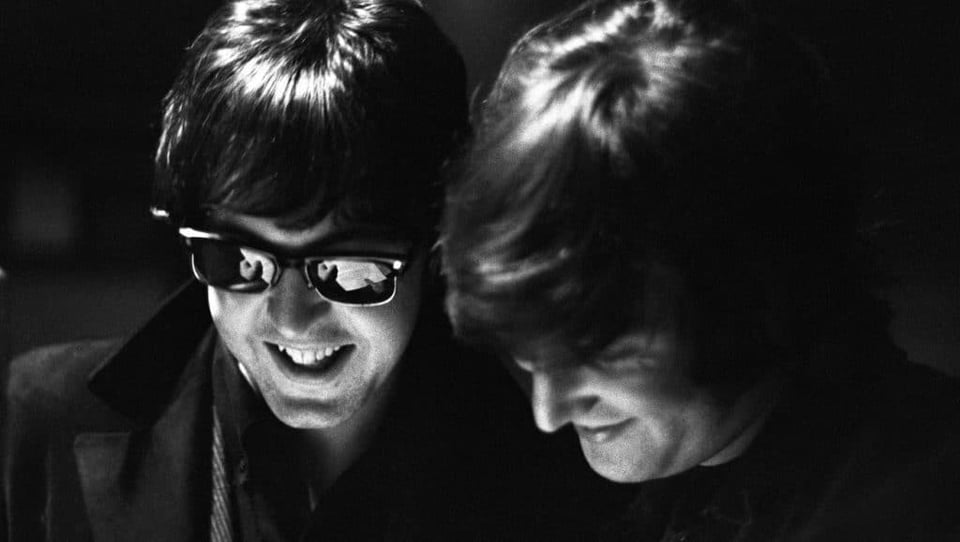

Paul takes the majority of the track, using it to process an argument he had just had with Jane, writing verses about trying to get his girlfriend to “see things [his] way,” and assuring her that they could… solve this issue. What makes “We Can Work It Out” such a fascinating single is that it’s a rare Lennon-McCartney song where, unlike “In My Life,” it’s INCREDIBLY clear who contributed what. The song switches up in the middle eight, taking a more downbeat tone as John comes in and laments how much time is wasted arguing when life is so short, a particularly poignant sentiment from him (why did this man write so many songs that would hit differently if he died young WHY DID HE DO THIS TO US). This switch between the upbeat Paul-led sections and the downbeat John-led sections is what makes the song such an interesting look into their songwriting dynamic, putting their different strengths on full display.

I agree with the consensus that “We Can Work It Out” showcases Paul’s optimism alongside John’s pessimism, but that’s not the only dynamic I hear at play in this track. Funny enough, I think there’s a reading where John comes out as the optimist on this song. Paul believes that the two can work it out, but his verses are filled with frustration, begging his partner to see his point of view and worrying about the possibility of the relationship falling through over this argument. You can easily read John’s middle eight as helping calm Paul down, reminding him of the senselessness of fighting and fretting over the argument after the fact. Life is very short, and there’s no time for fussing and fighting, my friend. I think it’s fun to reconsider their roles on this track instead of keeping them in the boxes of The Optimist and The Pessimist, although I fully understand why the primary reading of the track is what most people get out of it.

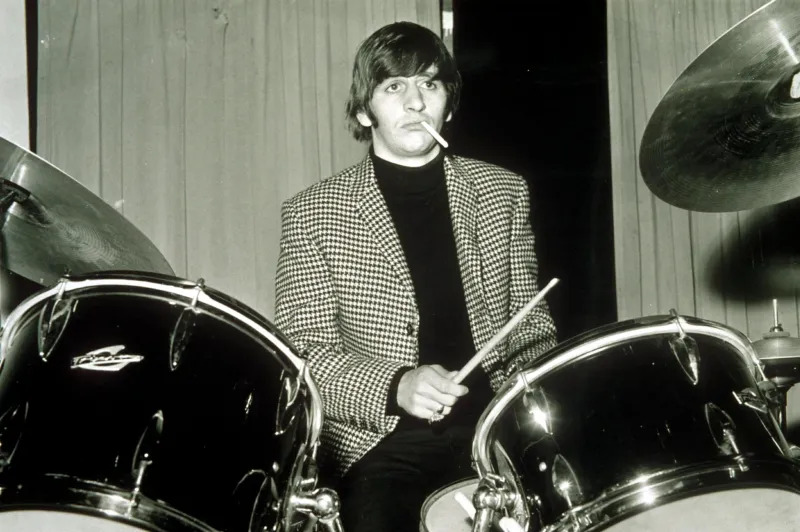

Most of the song was completed on the 20th, with the arrangement worked on in the studio by the full band. Notably, George gave a contribution that made John’s middle eight stand out even more. After four bars in 4/4, the song slows down suddenly and switches into ¾ time, or as the band loved to call it, “waltz time.” It’s very endearing to me that all throughout their career, the Beatles would always call ¾ “waltz time”, it makes their rare moments of varying time signatures all the more noticeable for me. Also, since I feel really bad that he hasn’t come up once in this analysis until now, Ringo nails this time signature change. He makes it completely seamless. I promise that Ringo will get his time to shine when his Rubber Soul song is recorded, but his contributions to the album are the perfect backbone for the rest of the band to flourish. I particularly love his drum beat on “In My Life,” giving the song the perfect amount of space to breathe where other drummers would take an opportunity to be more showy. He really is one of the best drummers out there. Shoutout Ringo.

After the rhythm track and vocals were down, John added the other notable piece of the composition, his harmonium. I LOVE this element. It’s not a particularly complex part, mostly a “basic held chord, what you would call a pad today,” as Paul explained in Many Years From Now, but it adds so much texture to the track. It’s held throughout the whole song, another example of the groups’ increased interest in drone, and gives it a lot of character.

Once additional vocals and harmonium were added on the 29th, the group, sans John, and manager Brian Epstein decided that “We Can Work It Out” would be their next A-side. John protested, believing that “Day Tripper” was the stronger song. Other times he may have had to just Suck It (see “I Am The Walrus” and “Revolution” later in the decade), but in this case EMI agreed to a first: The Beatles’ first double-A sided single, and one of the first double-A sides ever released. Both songs, which are nearly equal in quality to be fair, would receive equal promotion. Time would tell which song would prove to be more successful. “Day Tripper/We Can Work It Out” was slated to release alongside the Rubber Soul album, well on its way to completion.

The next song on the docket was another John number, and one of the most successful songs on the album, “Nowhere Man.” Work began on a rhythm track on the 21st, but the track was reworked the following day. “Nowhere Man” was arguably one of the biggest leaps forward in John’s songwriting on an album that contained seemingly nothing but leaps forward for the bandleader. Written on a lazy lonely morning at home, the song sees John moving further away from the love songs that made him famous and towards more introspection and even surrealism. It follows a man with no real prospects, no forward trajectory, and no interest in the world around him. Despite being written in the third person, it’s pretty clear that this was about John himself, who was struggling with his mental health and lack of drive during much of 1965. One of the last songs written for Rubber Soul, it’s very understandable why John’s mind would land on this subject matter during a period of writer’s block as time was starting to run out to complete the new album. It’s also a testament to the strength of John’s songwriting talent that he was able to write something so good and unique among his repertoire under these circumstances.

“Nowhere Man” is another song that pushed the band towards both folk rock and drone music. The song is drenched in harmonies and whirring acoustic and electric guitars, giving it a woozy character and making it one of the most atmospheric moments on the album. This layered instrumental, combined with its introspective, ambiguous lyrics, gives the song an almost proto-psychedelic feeling. It certainly sounded psychedelic for a band that had stayed mostly in a pop-rock lane up to this point in their careers. “Nowhere Man” was one of the two songs from Rubber Soul chosen for the 1968 acid trip of an animated film Yellow Submarine. The fact that this song fits perfectly alongside the psychedelic soundscapes the group was recording two years later is exemplary of just how forward thinking this track was.

So far the sessions had been dominated by John-penned tracks, but on October 24th, work began on a Paul cut that would take numerous sessions over the next few weeks to complete. Unsurprisingly, “I’m Looking Through You” is another song about Paul’s relationship issues with Jane Asher. Instead of processing the immediate emotions of the aftermath of a fight, this song sees Paul looking at the bigger picture, seeing that Jane was seemingly more committed to her career than to him, and processing his pain from that. It’s ironic for ANY Beatle to feel hurt over their partner’s non-commitment, but I digress. Despite having Terminal Cheater Disease, Paul clearly loved Jane, and his frustration and hurt over the state of their relationship. He laments that he “thought he knew [her]” and mentions that “love has a nasty habit of disappearing overnight.” It’s one of the most earnest and honest songs he ever wrote about this relationship.

“I’m Looking Through You” proved to be the most challenging song on Rubber Soul to complete. The band worked on it for four sessions, a rarity at the time. After extensive rehearsals on the 24th, they recorded a slower, bluesier rendition of the rhythm track, but were ultimately unhappy with the results of their single take. The song was shelved for two weeks, when another attempt was made on November 6th. This take was closer to the song we know today, ramping up the tempo and moving closer to the soul-infused pop-rock of the final version, but still didn’t meet the band’s standards. The song was attempted yet again at the end of the sessions, on November 10th and 11th, where it capped off the final two days of recording for the album.

Work was done to refine the faster arrangement from the 6th, and new elements were added, including an organ section played by Ringo that cuts like a knife at the end of every verse. “I’m Looking Through You” is another track on Rubber Soul that puts heavy emphasis on the soul. Paul gives a passionate vocal performance that ramps up in emotion throughout, ending each verse in a shout. The arrangement supports him, reminiscent of the punchy R&B coming out of labels like Stax at the time, accentuated best by Ringo on organ and George on guitar coming in forcefully to emphasize the frustration Paul feels on the track. It’s a great touch born out of the added time the group had to rehearse and arrange in the studio.

“I’m Looking Through You” is infamous among Beatles superfans for being one of the sloppiest songs ever put on a Beatles album. Few will argue against its quality, it’s a great song, but the recording itself is home to numerous little blunders that are easy to spot when you’ve heard the song enough times. The YouTube channel You Can’t Unhear This has a great video analyzing the recording of this song. There are a lot of elements that make the recording messier than the average Beatles song, with moments of percussion falling off beat and guitar playing that can sound weirdly unconfident for a player as talented as George Harrison. I’m not sure why these little accidents were kept in the final mix, maybe it was the chaos of the album being nearly finished at the time of recording or exhaustion from going through so many versions of the track, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. They’re a fun byproduct of the analog era, when it took a lot more work to remove these human imperfections from a track compared to the digital technology we have today. It gives the track character. It even works thematically with the track, a subtle, unintentional emphasis of the messiness of the relationship Paul describes here.

The next few days would be busy for George Martin, as the 25th and 26th were dedicated to mixing the completed tracks at the time, one day spent on mono mixes and the next on stereo. The Beatles couldn’t be bothered to come to the studio that day, they were just lazing about, goofing off, doing whatever they wanted… like receiving their MBEs and meeting Queen Elizabeth at Buckingham Palace. No big deal.

This little side quest was the closest the band came to experiencing that trademark Beatlemania chaos during the Rubber Soul sessions, with the group’s recognition from the Queen becoming a massive media spectacle, including thousands of screaming fans outside of the palace, a sight the group was more than accustomed to by this point. Despite future criticism from the band members, particularly John (and Ringo?), the four had very positive things to say about the experience, reveling in the opulence of Buckingham Palace and feeling very welcomed by the Queen, despite prior controversy from snooty conservatives objecting to their recognition. There’s also a really funny story where John claimed the four smoked weed in the bathroom before the ceremony, although George was quick to say they would never have done it, that cigarettes turned into weed when retelling the story, and the whole thing is a big misunderstanding. (Says Ringo in the Anthology doc: “I was too stoned to remember.”)

Returning to the studio as Members of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, the 29th was spent completing “We Can Work It Out”, as detailed earlier. As October turned to November, the group dedicated two days to filming The Music of Lennon & McCartney, a television special celebrating the young duo’s catalogue of songs and the massive roster of covers they had accumulated over the last two years. The special would air on Granada Television in December. While it was a fun week of excursions for the group, between the visit to Buckingham Palace and the TV recording in Manchester, it meant that when the band returned to London, they had less than two weeks to complete their next album. November 1965 is when the band would really be backed against the wall.

This urgent need for material would be felt on November 3rd, a day spent recording Paul’s iconic ballad “Michelle.” This track, a staple of the album seen as the band’s biggest leap forward up to this point, actually dates back to the late 50s. “Michelle” began as a party trick of all things, something a teenaged Paul would play to get attention from girls. He’d do his best to look romantic and mysterious and would pretend he could speak French in order to impress them. Y’know. Paul shit. Even then, the composition represented a step forward for the young songwriter, as he claims in Many Years From Now that “Michelle” was one of his first attempts to write a finger-picking guitar melody, like a classical guitarist would play. The young McCartney hadn’t heard the playing style until he discovered Chet Atkins, and sought to emulate the trailblazing country guitarist on this track. It’s a technique he’d use throughout his career, most famously on 1968’s “Blackbird.”

When struggling to fill the gaps of Rubber Soul, John reminded Paul of his old party trick ballad, and the two worked to flesh it out enough to be album quality. Specifically, John contributed the “I love you, I love you, I love you” middle eight, a piece of songwriting he’d later credit to Nina Simone. Speaking on the track in 1980, John would cite Simone’s rendition of “I Put A Spell On You” as his inspiration, and go on to explain what he saw as his role in the partnership. “My contributions to Paul’s songs was always to add a little bluesy edge to them… He provided a lightness and optimism, while I would always go for the sadness, the discord, the bluesy notes.” While “Michelle” is a strong contender for the LEAST edgy song the Beatles recorded, the middle eight does infuse it with some welcome R&B flourishes in Paul’s delivery, helping the romantic ballad stand out.

With the band now VERY pressed for time in the studio, it’s fortunate that “Michelle” was a very easy track to complete. Being a composition written when Paul was 16, it was fairly easy for the band to familiarize themselves with the arrangement. The rhythm track, which needed just one take, had both George and Paul on acoustic guitar. John overdubbed another acoustic part later in the day, leading to a beautiful intertwinning melody between the three of them. Bass, vocals, and a low-key guitar solo from George were added as well. This was all the simple, subdued ballad needed. By the end of the night, “Michelle” was complete, and so was over half of the album.

With a few exceptions, every Beatles album has at least one vocal showcase for the band’s reliable drummer, Ringo Starr. This would usually be a cover that was appropriate for his range, like country and rockabilly songs such as Carl Perkins’ “Honey Don’t” and Buck Owens’ “Act Naturally.” Occasionally, John and Paul would write a song specifically with Ringo in mind, like on With The Beatles’ “I Wanna Be Your Man” and the Help! outtake “If You’ve Got Trouble.” The next song recorded for Rubber Soul, “What Goes On,” was an old, unused Lennon-McCartney number that was reworked to fit Ringo’s voice, with help from the drummer himself.

“What Goes On” is another example of John and Paul digging into their archives for album tracks, reviving a song that existed as far back as the Quarrymen era and had been presented to George Martin back in 1963, though it was never recorded. In my opinion, you can definitely tell that this predates most of the Beatles discography in the songwriting. It’s a fairly by the numbers post-breakup song, with the narrator lamenting the pain he feels when he sees his ex with another man and the cruel, dismissive way she treated him during the relationship, asking her what goes on in her heart and mind when she treats him this way. It’s not a bad set of lyrics by any measure, but it’s fairly primitive compared to what the band was writing in 1965.

Where “What Goes On” shines is in its composition. As I noted earlier, Ringo tracks tended to be covers, and they tended to be covers within genres that fit his vocal range. Country and rockabilly, genres that would often highlight baritone singers, were fertile ground for Ringo covers, and they happened to be some of his favorite music anyways. It’s fitting then that “What Goes On” is some of the most classic rock ‘n’ roll you’ll find on Rubber Soul, with a country twang that helps the track stand out. The song has a jaunty, rollicking instrumentation that supports a simple yet effective melody that’s very infectious and easy to sing along with. While we can’t say for sure who contributed what, as there are no recordings of the song from before these album sessions, it’s speculated that Paul developed the melodic verses with help from Ringo. Writing music would never be Ringo’s forte, and his earnest attempts at songwriting wouldn’t really begin until later in the Beatles’ career, but this was still an important milestone for Ringo, giving him not only his first credit as a writer, but also making Rubber Soul the first Beatles album to have songwriting credits from all four members.

Recorded on the night of November 4th, “What Goes On” was yet another song the group was able to finish in the studio incredibly quickly. The song only needed one take and minimal overdubs to complete. The song doesn’t feature Ringo’s strongest vocals, but I think they fit the subject matter perfectly. There’s naturally a tinge of melancholy and wistfulness to Ringo’s voice, which is used to great effect on songs like “Yellow Submarine”, and it suits the heartbroken narrator of “What Goes On” very well. Ringo strikes a balance between upbeat and hurt on the song very well, allowing the feeling of the lyrics to come through without putting a damper on the upbeat rockabilly of the composition. Outside of the vocalist, the non-Ringo MVP of the track has to be George, who gives a stellar guitar solo to flesh out the track. He flies all over the fretboard, giving one of his signature melodic solos, this one reminiscent of his guitar hero Carl Perkins. It’s a highlight of the track and really ties the classic rock ‘n’ roll feel of the song together.

Having finished “What Goes On” with time to spare, and still in a bluesy mood, the group worked into the early morning on an instrumental jam, simply titled “12-Bar Original.” The song, which wouldn’t be released until the mid 1990s on Anthology 2, is… honestly not all that impressive, but it’s a fun look into the band’s musical synergy around this time. George is again the standout, with his bluesy guitar flourishes peppered throughout the track. You can also hear George Martin in the background, adding some texture on the harmonium. It’s unlikely that the song was ever in consideration for Rubber Soul, and the band members never had many good things to say about it (or anything to say about it at all) in the years following its recording, but I’m glad they had fun.

By this point there was just under a month until Rubber Soul was due for release, and just one week left of studio time, and there were still five songs needed to complete the record. The Beatles were in for a very productive week. That week began on Monday November 8th, when a late night session was spent on George’s second contribution to the album, “Think For Yourself.” Of all the songs on Rubber Soul, this is the one whose origin we know the least about. As good of a song as it is, and it’s pretty damn great, there’s not much of a story attached to this track. George doesn’t even recall who it’s about, despite its very pointed lyrics. The most we get for a backstory is George stating in his autobiography I Me Mine that he can’t remember who he wrote it about. “Probably the government.” Given how he made his thoughts on the government very clear on the opening track of Rubber Soul’s follow-up, I’m inclined to believe him.

What we do know about “Think For Yourself” is that it was a leap forward for George lyrically. It’s a pointed kiss-off anthem with Dylanesque surrealism mixed in. It’s a vague set of lyrics that can just as easily be telling off a woman as it could be social criticism of the government, possibly both at once. As David Rybaczewski for BeatleBooks points out, Beatle manager Brian Epstein had a strict policy against making overt political statements at this time, meaning any criticism George wanted to give would have to be cloaked in this style of up-for-interpretation writing. What I’m most impressed by is how good George is able to make these lyrics sound together. The way lines like “I left you far behind/The ruins of the life that you had in mind” and “Although your mind’s opaque/Try thinking more if just for your own sake” are delivered on this track just hit my ears in such a pleasing way, and they go a long way in giving the song a biting, aggressive tone, helping it stand out on an album that’s largely mellow and introspective.

Like many songs on Rubber Soul, “Think For Yourself” was able to be completed in one late night session. It was a familiar routine by this point. The group rehearsed the song as the session began, with George Martin recording these rehearsals in the hopes to use it for their annual fan club Christmas single, and were able to nail the rhythm track in a single take. The overdubbing gave the song its most distinctive features. It showcases some of the best three-part harmonies this band has to offer, with George, Paul and John melting into one slurred, surreal voice. I think the vocals on this track alone could justify it being considered proto-psychedelia, they truly sound otherworldly at points. The other distinctive feature is the aggression in the instrumental, most notably in George’s guitar and Paul’s bass. They’re both played more distorted than usual, with Paul’s bass being filtered through a fuzz box. These were very rarely used on bass parts at this time, giving the low end of the track a biting edge it otherwise wouldn’t have. With this, the track was complete.

Oh yeah and they were able to record something for their fan club. It may have just been them dicking around in the studio, but it was all four of them dicking around this time, so it was automatically better than their last effort.

After a day of mixing, the group returned on November 10th. This seven hour session was dedicated in part to recording John’s “The Word.” This track is a love song, but not like the ones they had recorded before. It was the first time the Beatles explored a topic that would soon define their image and music in the minds of millions: love, as a concept. Not directed at any one person, “The Word” is… love, and it’s a song exploring the way that love is a part of everyone and everything. It’s the “underlying theme of the universe,” as John would later put it. Unsurprisingly, this song was written under the effects of marijuana, a drug that gives you a heightened, existential awareness of the world around you that your brain tends to put on the backburner when sober. Not that I’d know anything about that. I lied. I’m a Californian. Of course I know about that.

Paul explained in Many Years From Now that the song began as an attempt to “write a song based around a single note.” He cites Little Richard’s “Long Tall Sally”, a Beatles concert staple, as an influence. They get close to this goal, with the song staying primarily on the D7 chord. Compositionally, “The Word” sits in an interesting middle ground between soul and psychedelia, with its spiritual subject matter being supported by an energetic R&B backing. The jaunty piano goes a long way in keeping the song upbeat, as well as being the clearest example of the track’s soul influence. It provides a great contrast to the harmonium, which showcases the trippier, droning side of the song. With “The Word,” the group were inching ever closer to the psych-rock explosion that was now just months away.

The November 10th session, which lasted until four in the morning, began with recording “The Word.” The song’s basic track is heavily tinged with R&B, being when Paul’s lively piano part was taped. The recording process for “The Word” was essentially taking this basic soul track and infusing it with trippier elements. With the song containing some of their most spiritual lyrics yet, it makes sense that John’s vocals take on an almost preacher-like quality, encouraging listeners to spread the word of love as he is on the track. It’s very Beatles of them to not endorse any specific spiritual beliefs (not yet anyways), but rather to just encourage their audience to spread love and kindness to the people in their lives. This religious aspect of the composition is heightened not just by John’s intense delivery but also by the use of maracas and hand percussion, as if the track was recorded at an actual religious gathering. Many Beatles songs from this time use instruments like maracas and tambourines for added texture, but they’re particularly effective here in enhancing the tone of the track. The real psychedelia comes from the aforementioned harmonium, which was played by George Martin. It gives the track a mystical quality that ties the whole song together, especially when it’s played on the outro as the song fades out. “The Word” was able to be completed in this session, and the groundwork was laid to finally finish “I’m Looking Through You” as well. Three songs left.

The following day, November 11th, would be the final recording session for Rubber Soul, and an incredibly productive one. On this day, the Beatles were able to complete the remaining songs needed to give the album an even 14 tracks. Especially convenient for me, these last songs all touch on running themes that permeate Rubber Soul and help it stand out within the Beatles discography. Ending these sessions with “You Won’t See Me”, “Girl”, and “Wait” puts a nice bow on the month of recording, which this writer greatly appreciates.

First on the docket was Paul’s final contribution to the record, “You Won’t See Me.” Right off the bat, I think this is the most underrated song on Rubber Soul and potentially the most underrated song on any Beatles album. Like “We Can Work It Out” and “I’m Looking Through You” before it, this song sees Paul working through his relationship issues with Jane Asher in song. It’s another song written while Jane was away, focusing on her career in theater, and sees Paul processing his frustration with not being able to see her and talk with her as much as he’d wanted to. He’s desperately lonely on the track, his days are fiiilled with tears, and since he’d lost you it feeeeels like years. You’d be forgiven for thinking this was a full-on breakup song with the way Paul describes his separation from his lover on the track, though Paul and Jane would stay together for another two and a half years.

The subject matter may be interesting, but what really makes me gravitate towards “You Won’t See Me” is its composition. It’s an expertly crafted song. Paul considers the track to be very “Motown-flavored,” and you can really hear this in the tightness of the instrumental and the melody in Paul’s bass playing. Motown was known as something of a pop music factory, a streamlined, Henry Ford-esque process of pop songwriting and production that resulted in some incredibly tight, thoughtfully composed pop music that sticks in people’s minds. You can hear this clearly in the composition of “You Won’t See Me.” The song is driven by Paul’s piano playing, giving the track a tinge of R&B and early rock ‘n’ roll. I know I keep using this word, but if there was anything on this album worthy of being called “jaunty,” it’s this song’s piano line, giving this potentially downbeat song a much appreciated jolt of life throughout the track. It’s also supported greatly by one of Paul’s best basslines, another James Jamerson inspired performance that’s melodically inclined and easy to pick out within the song, but never drawing attention away from its other elements.

The other musical MVP of “You Won’t See Me” isn’t actually a Beatle at all, but one of the closest friends of the band. Mal Evans was, on paper, the Beatles’ road manager, but it’s more accurate to call him their gofer. He was a constant presence with the band and an incredibly reliable friend, always willing to grab them a drink or a pack of cigs or write down lyrics for them, willing to do whatever they needed because he loved the group so much. He would occasionally play a role in the tracks as well (you can hear him playing on the final chord of “A Day In The Life” for example), and he plays a quiet but very important role on “You Won’t See Me.” After the rhythm track was nailed in the studio, a number of vocal and instrumental overdubs were recorded to flesh it out. One of these consisted of Mal, playing a sustained note on the Hammond organ that lasts for most of the track. It took me years before I even realized this note was there, but thankfully I’ll never be able to unhear it. That note is the rock, the thing that ties the whole composition together and keeps things grounded as Paul flaunts his skills. It may just be one note, but it feels like an apt metaphor for Mal’s unsung role in the Beatles story as a whole.

Unlike “In My Life,” I don’t have a very deep reason for why this song is my other favorite on Rubber Soul. No personal anecdotes about it. This is just a song by pop’s greatest melody writer, taking direct influence from some of the best pop craftsmen in history. It’s a great song to sing along with, and every element is performed brilliantly. Throughout all these years it’s stuck with me just by being a damn great song.

“You Won’t See Me” was in the tank, but there was still a lot of work left to be done. The next song of the night was John’s lauded acoustic ballad, one often cited as yet another showcase of his improving skills as a writer, “Girl.” This was one of the Beatles songs John was most proud of after the band split. Despite, or maybe because of, the fact that the song was written about a make-believe dream girl, John felt the lyrics to be incredibly honest and real. As Beatles Bible contributors describe it, he presents the titular girl as being a femme-fatale figure, a mysterious girl who John can never have and who continuously breaks his heart, and yet he can’t help but be drawn to her. The song also takes aim at the idea that you need to suffer for success, that you have to go through pain to get what you want, with lines like “Did she understand it when they said/That a man must break his back to earn his day of leisure/Will she still believe it when he’s dead?” John told Rolling Stone in 1970 that this was a subtle way of criticizing Catholicism, saying that he “didn’t believe in any of that, that you have to be tortured to attain anything, it just so happens that you were.”

Musically, the song has something of an exotic quality. The beginnings of this composition date back to 1963, when Paul was vacationing in Greece. Inspired by the music of the country, he wrote a short ascending and descending melody played on a bouzouki. This would eventually be performed on acoustic guitars near the end of “Girl.” This may be the only part of the song with explicit influence from another culture, but the downtempo, minor key track stands out on Rubber Soul, with its layers of acoustic guitar parts and exquisite, swirling vocal harmonies. It all comes together musically to emphasize the mystical nature of the song’s subject, and it’s done so beautifully.

“Girl” may be one of the darkest moments on Rubber Soul, but it also subtly contains some of the most mischievous moments on the whole album. Possibly the most striking moments of the whole song are the moments where John breathes in during the chorus. They’re surprising moments of punctuation between the dreamy harmonies of “giiiirl…” and can be heard as a wistful, contemplative moment as our narrator considers all the conflicted feelings this girl gives him. Or it could be a sneaky reference to marijuana. Rubber Soul was their weed album after all, and the Beatles loved to sneak more explicit themes into their music under the radar. The whole song is very relaxed and contemplative and essentially puts the feeling of a good high into song, so even if this was a bunch of young stoners being goofy and rebellious on record, I think it suits the song perfectly.

The other moment of silliness in the studio can be heard in the backing vocals during the middle eight. As Paul describes in Many Years From Now, the band were trying to come up with a variation of their usual “la la la” to add to the track, which started off as them going “dit dit dit” before it morphed into “tit tit tit.” Talk about sneaking in explicit themes. The boys were careful to give themselves some plausible deniability, and wouldn’t admit what they were really saying on the record, but they knew. Truly, “tit tit tit” walked so “po-po-po-poker face fu-fu-fuck her face” could run. I love stories like this because it shows that the group were still in good spirits and having fun, despite the quick turnaround and long hours in the studio. Recording for “Girl” went smoothly overall. The only thing left on the cutting room floor was an electric guitar part played by George, but given how strong the atmosphere on this track is with just acoustics, I don’t think it was necessary. With that, the group had two songs down, but they couldn’t rest just yet.

“Girl” was the last new song recorded for Rubber Soul, but that left them one song short of their ideal number 14. Needing one last song, the band once again dug into their archives, and out came “Wait.” This was a Help! era track, written while on location in the Bahamas and originally recorded in June of 1965. It’s a fairly basic track, a love song about being apart from your partner, but being able to keep going through the faith in knowing you’ll be together again soon. Even if it was written before the Rubber Soul sessions, when Paul was the one traveling for work, it almost feels like a response track to songs like “You Won’t See Me,” showing the love Paul and Jane had for each other, despite the distance, whether physically or emotionally. It feels like the end of a thematic arc, even if the reality of the song’s history doesn’t lend itself to that neat narrative.

“Wait” was nearly completed in the studio, but ultimately went unused until it was rediscovered and dusted off during the November 11th session. At this stage, the bones of the track were there, Paul and John’s vocals as well as the basic instrumental. All it needed now was some additional touches to flesh out the track and make it cohesive with the rest of the album. This consisted of adding extra vocals, percussion, and guitar parts. These guitar overdubs used volume pedals, giving George’s playing a particularly dynamic feel compared to much of his work up to that point. Hand percussion was overdubbed as well, with John on the tambourine and Ringo on maracas. These additional overdubs give “Wait” a newfound energy, an added layer of excitement that underlines the optimism at the core of the track. Whether this excitement was because the band knew they were in the home stretch of recording the album, I can’t say. But after refining the once-shelved track, their work on Rubber Soul was finally complete.

Just kidding. “I’m Looking Through You” still needed completion. The session concluded by adding lead and backing vocals from Paul and John onto the finalized backing track recorded the previous night. When this concluded, it was seven in the morning, and the Beatles had been in the studio for 13 hours. There was more mixing and editing to be done for George Martin and the engineers at EMI, but for John, Paul, George and Ringo, a month’s worth of innovation, rehearsing and tight playing in the studio had finally paid off. A weight was lifted off their shoulders.

It was November 12, 1965, and Rubber Soul was finished.

After making the final mono and stereo mixes, George Martin sequenced the album. Famously, Rubber Soul was meant to be heard as a full album statement, rather than a simple collection of singles and filler tracks, like how many pop albums were meant to be heard in the 1960s. With the tracks from the last month of studio time having comparable instrumentation and numerous throughlines between them, George Martin was able to make a very cohesive record out of these tracks. The final running order for Rubber Soul would go as follows:

Side A

Drive My Car

Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)

You Won’t See Me

Nowhere Man

Think For Yourself

The Word

Michelle

Side B

What Goes On

Girl

I’m Looking Through You

In My Life

Wait

If I Needed Someone

Run For Your Life

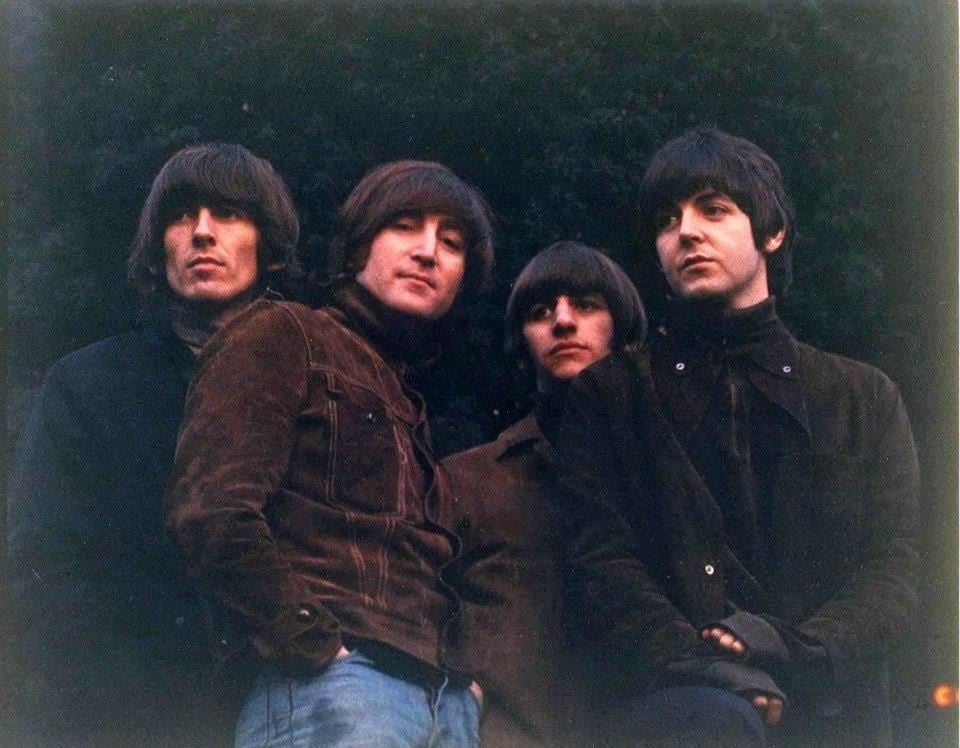

This is the tracklist that would appear on UK versions of the album, showing off the mix of soul and folk inspired tracks that defined the sound of the Beatles around this time. The album would be packaged in a striking, distorted photograph taken by Robert Freeman of the band standing against some greenery at John’s house, a fitting match for this pastoral and slightly psychedelic record. It was also their first album cover to not contain their name on the front, a testament to the Beatles’ popularity by this point. The Beatles’ sixth studio album, Rubber Soul, would be released alongside the double A-side single “Day Tripper/We Can Work It Out” on December 3rd, 1965.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the changes made to the US release. The Beatles’ American label, Capitol, spent years making adjustments to previous Beatle releases, often taking tracks from UK albums and frankensteining them into new projects; this is why the group had twice as many albums in America as they had in Britain. Folk rock was in full swing in the States in 1965, and with Rubber Soul, Capitol made an effort to promote the album as a folk rock LP. Help! tracks “I’ve Just Seen A Face” and “It’s Only Love” open each side of the record, replacing “Drive My Car”, “Nowhere Man”, “What Goes On” and “If I Needed Someone.” These more rock-heavy tracks would be issued in 1966 on the Yesterday And Today album, the one with the infamous Butcher Baby album cover, with the band covered in raw meat and doll parts, it was a whole thing. “Nowhere Man” and “If I Needed Someone” strike me as particularly egregious cuts, as they’re some of the definitive folk rock songs in my mind, and it’s hard for me to imagine Rubber Soul without these tracks. But this version of the album directly led to Brian Wilson making Pet Sounds so what do I know?

Yeah, Rubber Soul was received very well on both sides of the Atlantic. Commercially, the Beatles had nothing to worry about. Rubber Soul topped the album charts in the UK, US, Canada, Australia and West Germany, becoming one of the bestselling albums of 1965 and 1966. It reportedly sold over 6 million copies in the US alone. On the singles chart, its impact could be felt as well. “Day Tripper/We Can Work It Out” shot to #1 in the UK, becoming their seventh #1 hit in a row. In America, where the tracks were separated on the Hot 100, “We Can Work It Out” spent three weeks at the top, while “Day Tripper” made it to #4 (Sorry John, Brian was right). “Nowhere Man” was also released as a single in the US, backed by “What Goes On”, and peaked at #3 in the spring of 1966. These tracks not being on the American LP helped give it the feeling of a self contained record more than any Capitol album up to that point, as the Beatle rule of not putting singles on the album didn’t usually apply to American prints. “Norwegian Wood” and “Michelle” were also released as singles across the globe and found commercial success.

Many contemporary critics were able to recognize it as a leap forward for the band, with writer Phil Hall calling it “a successful experiment” in different styles and effects, and was considered by Allen Evans for NME to be a “fine piece of recording artistry and an adventure in group sound.” The groups’ burgeoning maturity and expanding musical palette was satisfying critics who were always in their corner, as well as converting sceptics. Some weren’t sure of what to make of the surprisingly cohesive LP, with Melody Maker considering some tracks “monotonous” and Record Mirror lamenting the lack of variety on the album, which I straight up don’t understand, especially considering they were a British magazine and had the more well-rounded LP. But even these critics had to give credit to the musicianship and songwriting talent that was clearly on display throughout the record.

Rubber Soul elevated both the Beatles and pop music as a whole in the cultural conversation. It’s often seen as one of the first great albums of the rock era, and while 1965 also saw landmark releases from Rubber Soul influence Bob Dylan, the Beatles had an approachability and pop sensibility that allowed the album to lift up many of the group’s rock band contemporaries into a new realm of respectability and acclaim from critics. Pop and rock fans understood the complexity of the record better than anyone else, and this prompted responses from people all across the pop world, from the creation of Crawdaddy! magazine and rock journalism, to lighting a competitive fire in Brian Wilson that led to him creating his masterpiece. Until they topped themselves a year and a half later with Sgt. Pepper, Rubber Soul was recognized as the high watermark for artistic statements in rock ‘n’ roll. All this for an album that was rushed out for Christmas!

So, they did it. For the umpteenth time in just three years, the Beatles defied the odds and conquered the world. And what they did next was potentially just as revolutionary as their previous album… they took a break. A real deal, no bullshit, break.

1966 was meant to be a repeat of the last two years. Constant touring, constantly recording, filming a movie in the spring. Robert Rodriguez writes in his book Revolver: How The Beatles Reimagined Rock ‘N’ Roll that the film was supposed to be a western comedy where the Beatles played actual characters, rather than the heightened versions of themselves that appear in their previous two films. When the film fell through due to the band’s unhappiness with the script, they suddenly found themselves with three months of freedom. They were able to rest on the success of their previous effort, and rest in general. When they returned to the studio in April, they were brimming with ideas, and wanted to push their sound further than they ever had. They delved deep into Indian-inspired music, they were composing pieces beyond the standard four-member rock songs they’d previously recorded, they were using the studio as an instrument like no pop group before them. And all of it was a continuation of what they did on Rubber Soul.

To me, Rubber Soul, and the three months of rest that followed, is the bridge between the cuddly pop heartthrobs of their early years, and the innovative rock legends of their later work. Even when pressed for time, forced to scramble together an album so their record label could have a good fourth quarter, the Beatles were evolving. As they matured, so did their songwriting. As they experienced more in life, their subject matter grew wider. As they rehearsed in the studio for hours at a time, their playing got better, both as individual musicians and as a band. They got more comfortable and capable in the studio, and it led to them taking more risks. They perfected their pop abilities while also learning how to construct a cohesive LP, where the album as a whole could be greater than the sum of its parts. And when they were able to do all this in just a month of studio time, they knew the sky was the limit. Rubber Soul changed things for the Beatles. It gave them the confidence to make their late 60s masterpieces.

And yet, Rubber Soul is a masterpiece in its own right. It contains many of the group's strongest melodies, gorgeous harmonies and impeccable instrumentation. It’s a snapshot of who they were at this time, whether that be John struggling with his mental health, Paul struggling with his relationship, or George on the brink of enlightenment. It’s an introspective, revealing work. It’s a loving tribute to all of the rock and R&B that inspired the group and informed their sound. All of these elements come together to make Rubber Soul my personal favorite record the Beatles ever released. It’s like John would say in similarly stressful conditions three years later: when their backs are against the wall, you’ll find the Beatles are at their best.