Words Matter

The words used to describe digital technologies might not seem important, but they matter very much. On Pat McFadden's recent speech and the general trend towards technology heroism.

Digital technologies require a strange combination of seemingly unconnected things, including (but not limited to) big material things like data centres, small things like phones and computers, even smaller things like chips and processors, and a bunch of invisible processes and protocols that conjure tools and services and apps and web pages and all the rest into being. What we see at the end tends to look quite neat and tidy, but many decisions and things are hidden behind those icons and dashboards and shiny cases, so they need great big stories to talk them up and make them feel exciting.

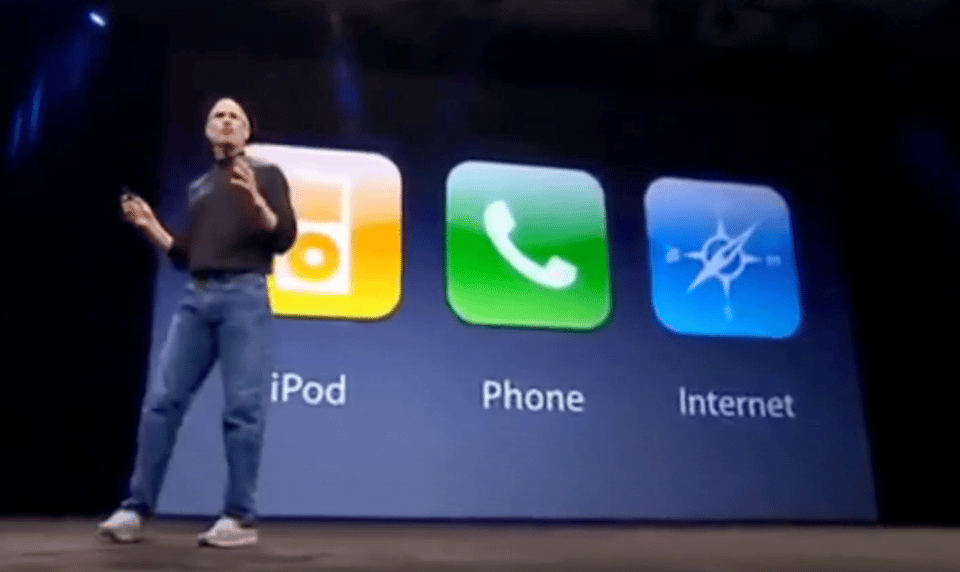

One of the things that built Apple’s runway to greatness was the fact that Steve Jobs could get people literally screaming in the aisles at a product launch while he paced back and forth planting magical triptychs of new products.

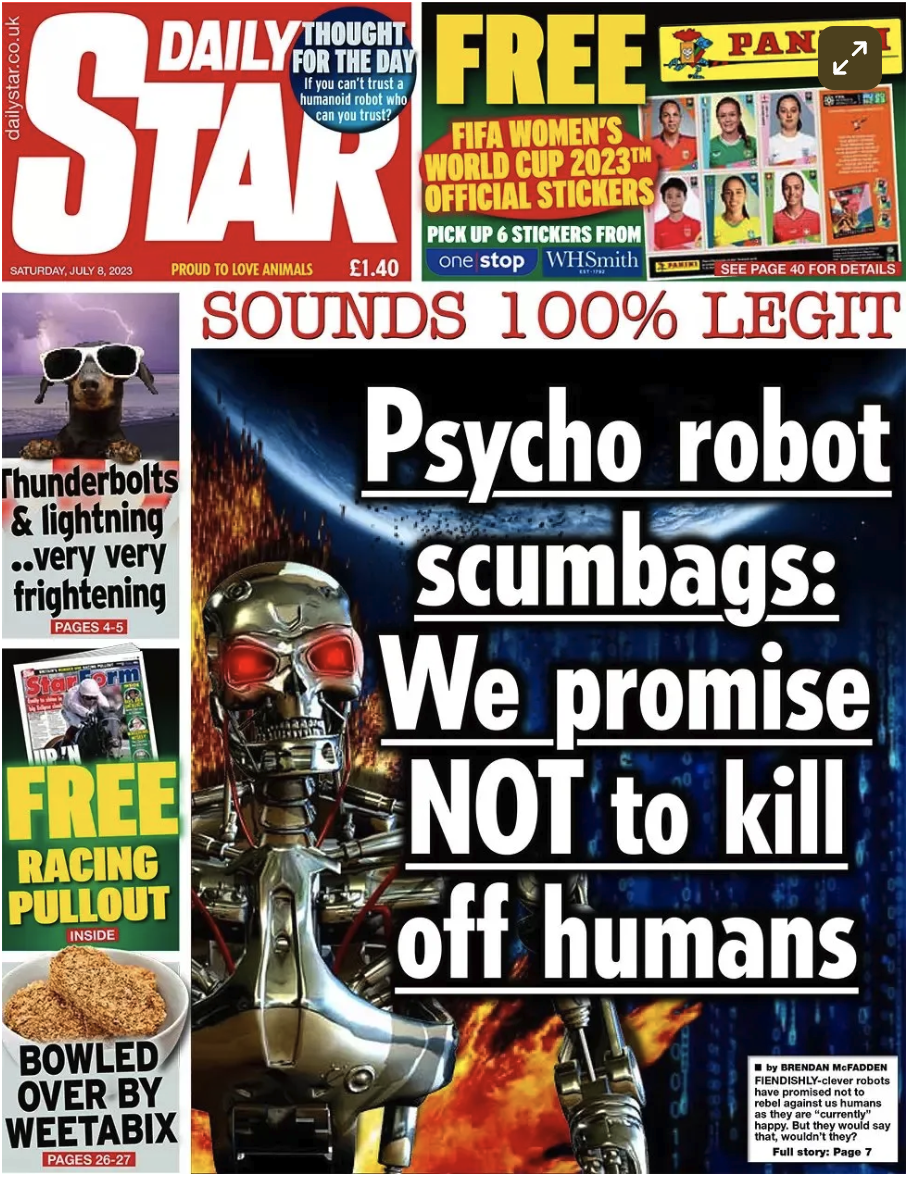

This kind of excellent marketing has played an important role in creating the current economic and social reality of digital technologies. And these words are used for both hype and for panic: the (p)doom Summer of 2023, when The Daily Star was running front page stories about AI Safety (which I wrote about in the Harvard Data Science Review), the current Crypto spike, Elon Musk buying Twitter, the Australian smartphone ban – these are all the result of words on web pages and apps, in speeches and in ads.

A recurring theme of these narratives – which are often really about maths, metals and undersea cables - are the heroic visionary qualities of men who spend a lot of time sitting at laptops. These warriors of the knowledge economy are often emboldened by science fiction stories that intertwine the known and unknown, the awesome and mundane to weave other worlds and possibilities. And while these stories don’t much figure in the GCSE Computing curriculum, they are a significant technological force that directs the flow of money and attention. It’s not just history that is told by the victors; they also get to dictate the future.

Politically, we are in a moment when stories and words matter a lot, so how the government of the day talks about technology is very significant. Personally, I do not feel minded to go soft on government capabilities in this area: good communication is a core political competency. Every word said by a cabinet minister in a public speech should be significant.

Which brings me to a speech yesterday by Pat McFadden. McFadden’s job title is Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, in itself a magical way of saying he’s the second most important in the Cabinet. Many people who have worked in digital government for many years found lots to like about it, and I am sure they are right about the delivery implications.

However, I did not love the use of language and metaphor, which drew on some of the worst bits of technological hero culture.

Firstly, the phrase “internet era”.

Back in the heyday of the Government Digital Service, I got in trouble with some people I really like a few times because I mentioned that some of the paradigms that have defined the “internet era” were Fairly Problematic. For a start, building for scale is not the same as providing a universal or an inclusive service; building for scale involves picking winners and losers and asserting dominance. There is not, for instance, much commonality between the NHS Constitution for England, which foregrounds universal care, and Silicon Valley entrepreneur Reid Hoffman’s guide to Blitzscaling, the bible for scale, which focusses on risk and uncertainty. While McFadden makes the point that public services need to take more risk, risks in digital government can be extremely consequential, and not all risks have the same implications. For instance, the eVisa roll-out has been delayed because the technology doesn’t work to a consistent standard while an AI system used by DWP was found to show “statistically significant” bias in selecting who to investigate for fraud.

Using scale-driven techniques to deliver care is like using a hammer to look after a baby: it introduces the wrong kind of risk. Healthy risk approaches come from strong teams working well together, who are given enough latitude to try things out. That’s not just an internet thing; it’s a mark of good leadership.

In his discussion of the Internet era, McFadden also focussed on three Fairly Problematic companies, that all do very different things to the things that public services do.

AirBnB, WhatsApp and Spotify have all picked winners and losers in the service of their growth: AirBnB has severely disrupted housing supply for local residents in tourist destinations and is now banned or restricted in many cities and beauty spots around the world; WhatsApp has become default privately owned public infrastructure, effectively taking a monopoly on private messaging; and Spotify’s royalty system prioritises profit for the company over paying artists. Perhaps Google Maps and Wikipedia would have been better picks, but the point is really that public services should be effective, not disruptive.

Secondly, “we can make the state think a little bit more like a start-up” is a bit like comparing apples with articulated lorries. A start-up is a founder-led business that takes investment, defined by Investopedia as:

a company in the early stages of its operations. Startups are founded by one or more entrepreneurs who want to develop a product or service for which they believe there is demand.

These companies generally launch with high costs and limited revenue, which is why they look for capital from a variety of sources such as angel investors and venture capitalists.

Startups typically require several years to make a profit, so significant, high-risk investments typically are needed to get one off the ground.

Meanwhile, the government “runs the country and has responsibility for developing and implementing policy and for drafting laws”.

This comes hot on the heels of Peter Kyle saying that Britain should treat tech companies like nation states. It’s as if someone has thrown all the words in the dictionary up in the air and let them land in the wrong places. I mean, yes, sure, test and learn away, but testing and learning is not the defining property of a start-up – testing and learning is just a project-management approach for delivering software. Software is made by all kinds of people and organisations all over the world; most start-ups are not known for their beautiful code but for successfully selling ideas. Absolutely be ambitious and reforming, but describe the thing as what it is, not as something that sounds a bit sexy in a headline.

The third is invoking the language of war. McFadden wants to conscript some digital heroes.

The press release that went alongside the speech referred to “crack teams” of digital experts; this term is thankfully missing from the actual speech, which calls them “test-and-learn teams” but – as James Cronin pointed out to me on Bluesky – the concept of a “Tour of Duty” remains.

I don’t have space here to talk about what an absolute shit show it is to be a woman in the technology industry. The reason I run my own organisation (some might even call me a start-up founder) is because sexism runs through tech like a river and life is too short to be constantly looking for a lifeboat. Like Tina Turner said, we don’t need another hero – and while public service is an honourable, essential calling, it’s not one that needs to be militarised to become high status.

Taking care of others is the very most important work there is to do; developing and delivering public services could well be framed as high status but that needs a change of frame, one that prioritises care and attention over muscularity and scale. That might seem like a risky choice, but I suspect it’s a risk worth taking.

I would like to see the government do better at technology communications. Words matter; they put Trump in the White House with Elon Musk at his side. The UK Government can forge its own way of doing digital and shouldn’t feel that it has to walk in the shadow of DOGE or AirBnB to be effective. It can take the right kind of risks and do something altogether bolder and braver than simply copying how software was shipped in 2010.

I’ll close with this wonderful provocation from Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble:

“It matters what matters we use to think other matters with; it matters what stories we tell to tell other stories with; it matters what knots knot knots, what thoughts think thoughts, what descriptions describe descriptions, what ties tie ties. It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.”

—-

PS!

At Doteveryone we did a short programme of work that explored the power of science fiction to make new myths and technological imaginaries. As part of that we published the collection Women Invent the Future, featuring stories by Becky Chambers, Molly Flatt, Madeline Ashby, Walida Imarisha, and Liz Williams. There aren’t any print copies left, but - if you’d like a palate cleanser - you can still download it from that page as an ePub.