Let the Right One In: Growth, Big Tech, vampires, and moats

As Elon Musk rampages through Washington, what does it mean for UK tech policy?

A week is a long time in tech policy.

This time last week, everyone was talking about the Chinese open-weight model DeepSeek, which wobbled Nvidia’s stock price and made Sam Altman call for a wambulance. This morning, not nearly as many people are talking about OpenAI’s newly launched “deep research” (see what they did there?), their second launch in under a week, because almost everyone is talking about the fact that Elon Musk is staging a coup.

Over the last few days, Musk and his team at DOGE have been tearing down US digital public information and research infrastructure, trying to get civil servants to resign over email, and giving a group of inexperienced engineers access to federal systems. (For a summary of where things stand in Washington, Ariel Kennan wrote this on LinkedIn on Sunday 2 February and is updating on Bluesky; the volunteer-run Internet Archive is meanwhile acting as a public back-up of state information, and Wired.com is covering the situation on a rolling basis.)

Meanwhile, this week’s Paris AI Summit will no doubt be a time for dignified set piece announcements and high-level accords, but these will be played out against a scarcely credible backdrop that veers between being very VUCA and extremely SNAFU. Hopefully, there will be more of this sort of news from CERN, but it feels very important to recognise that the AI news cycle currently belongs in a dysfunctional playground rather than on the global political stage.

In this context, it’s worth turning an eye to UK tech policy.

Since Labour took power in June, Peter Kyle has firmly repositioned DSIT as a department of economic delivery. This feels in line with the Chancellor’s push towards “doing doing doing” to get growth moving. Overall, the signal being transmitted is that the UK is a modern, deregulatory, investment-ready economy; our fusty old institutions of government are being shaken up to be “more like a start-up” while the grey belt is shovel-ready for data centre construction. The overall purpose is to attract as much inward investment as quickly as possible but it is not yet clear what comes after the investment blitz - and what happens if it doesn’t work.

However, as US tech policy unravels at speed, the UK government needs to start signalling which context it’s operating in. Are we going to move closer to Europe, China, or the US? Will we signal to mid-size US companies and researchers that the UK is a plausible alternative to Trump’s America, with a more lightweight regulatory environment than Europe and proximity to Brussels – or will we double-down on attracting Big Tech dollars, in the knowledge that it will draw us nearer to Trump?

So far, the Government has been very warm towards Microsoft, with Clare Barclay, the CEO of Microsoft UK, also chairing the Industrial Strategy Commission. Satya Nadella was one of the few Big Tech CEOs not to be in pole position at Trump’s inauguration, preferring instead to be photographed with Rachel Reeves at Davos a few days later. Given Peter Kyle’s assertion that the UK should treat tech companies like nation states, perhaps the preferred option is to go it alone in geopolitical terms, and ally more closely with Microsoft?

Any clear alliance the UK forms in the coming weeks should be a deliberative choice not a happy accident. Our tech partnerships of choice are not simply a matter of growth and investment; the after-effects of the decisions Labour makes now will ripple through the entire political economy and shape our democracy for decades to come.

This is particularly important because Rachel Reeves has announced her ambition for the Oxford-Cambridge Growth Corridor to be “Europe’s Silicon Valley”. Growing hyper-productive innovation places is not simply a top-down policy decision or the product of putting researchers in a room together, it’s also a cultural and ideological undertaking. (British bureaucrats should not, by the way, be trusted with naming innovation zones. Those of us old enough to remember Silicon Roundabout - David Cameron’s pet project, jokingly named after a traffic management feature and then adopted as a policy priority - will probably not be surprised we’ve downgraded to a “Growth Corridor”, which sounds like a menacing new development in Severance rather than a world-leading innovation opportunity.)

The history of Silicon Valley is not just about technological capability - it’s also filled with friendships, rivalries, and ambitions: Margaret O’Mara’s The Code, Sharon Weinberger’s Imagineers of War and Fred Turner’s Counterculture to Cyberculture show the innovation culture that arose in California after WW2 is just as much a human story as it is a tale of scientific breakthrough. While Marianna Mazzucato has written about the importance of state investment in the Valley, the confidence and urgency of gaining power and military success - of wanting to win at all costs, at all scales - was also a personally and politically animating factor for many early Silicon Valley innovators. Beating Russia to the moon and looking stylish while they did it catapulted early advancements into being breakthroughs of national and international interest; the clarifying early edict wasn’t simply “growth”, it was giving a relatively small group of mostly likeminded men the permission to go off in pursuit of world domination.

In fact, Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, a paper-based social network for innovators, declared in 1968 “we are as gods and might as well be good at it”. There is no humility here, and that godlike energy has been transmitted through the decades, as documented in Timnit Gebru and Émile Torres’ paper The Tescreal Bundle and writ large in 2025 by Elon Musk’s Nazi salute.

If Labour’s commitment to growth is underpinned by a commitment to democracy - by the understanding that a failure for living conditions to improve will let the light in for Reform’s brand of extremism - it is essential to also understand that digital technologies do not just have economic impacts. The vast financial power of a few men and a few Big Tech companies is not something the UK can leverage for short-term gains and then walk away from; whatever decision is made will be consequential for British society - perhaps not this year or next, but in the long-term. This may seem like a distraction from Project Growth, but the UK’s alternative to Silicon Valley needs to be animated by a vision for a more equitable, sustainable future for everyone. If we want to copy Silicon Valley’s successes, we must also learn from its mistakes; there is no point in growing the economy in a hurry if we do it in a way that lets the political demagogues in.

The AI Copyright Consultation is one opportunity for signalling intent. The Creative Industries are a significant source of both income and soft power for the UK – one that we currently appear to be intent on giving away to OpenAI and others that leverage LLMs to develop AI systems.

The Government’s current proposals are a short-term bid for investment and a future bet on tentative income, much loved by the technology YIMBYs. But in the last week DeepSeek has shown that OpenAI’s model may not be quite as foundational as they hope. High pressure competition between the US and China over the next year could fundamentally shift the direction of development, while the deregulatory preferences of Trump’s government are likely to lead to new risks and rights abuses. Matt Clifford’s AI Opportunities Action Plan assumes AI will stay big - leveraging high levels of compute and requiring massive data sets - but that is only one possible future. If the UK goes all in on that model only for it to flounder or be in robust competition with smaller, more sustainable approaches, then the price for us is high. After all, sovereign capability is not simply about skills and infrastructure; it also requires culture and capability.

Moreover, in the context of a Trump government and the commencement of the EU AI Act Prohibited AI Practices regime, the UK might - momentarily - have a new advantage. More lenient than Europe, less deranged than the US, we can still be a very attractive prospect for inward investment without having to give everything away.

And rolling back on this is not hard. With excellent timing, Beeban Kidron has swept into the House of Lords with an amendment to the Data (Use and Access) Bill that supports the Creative Industries and could reassert the UK’s independence. Already passed by the Lords, the amendment now needs to get through the Commons. With the consultation still open, the Government can legitimately weigh the balance of evidence with the knowledge that not settling for an opt-in, rather than an opt-out, model would build us a democratic moat and grant us some very important independence.

The AI Copyright debate is not just about data; it’s fundamentally about power, and now is not a good time to give that away.

Gratuitous self-promotion!

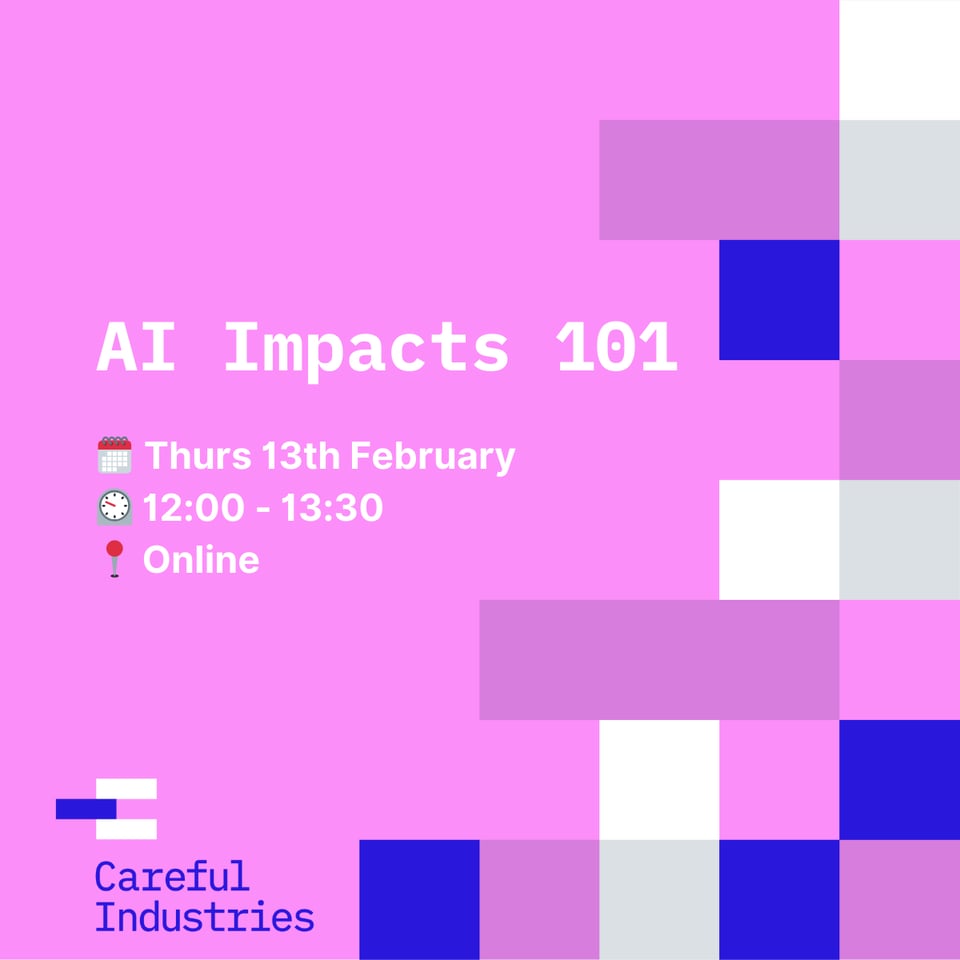

New bookable workshop: if you want to improve your AI literacy and learn more about the social and environmental impacts of AI, I’m running two Careful Industries virtual training sessions:

AI Impacts 101: 12-1:30pm, 13 February 2025

AI Impacts for Charities and Public Services: 12:30-2pm, 4 March 2025

New Careful Industries Green Paper on Inclusive Innovation and Technology Diffusion, commissioned by Phoenix Court