Is it possible for general purpose AI to do no harm?

This edition is a write up of most of the things I wanted to say at the Young Pugwash Conference on Saturday. The theme of the event was AI, Peace and Security, and I spoke about some of the risks emerging at the intersection of technology development, multilateral AI governance, and global volatility and warfare.

It was also a real pleasure to finally be on a panel with Matt Mahoudi from Amnesty International. I was so impressed with the forensic detail of the work Matt presented, in particular the Ban the Scan project, which goes under the hood of facial recognition technologies in NYC - something that will become more pertinent in the UK as facial recognition is rolled out in more and more contexts without sufficient standards or scrutiny. This isn’t just an issue of privacy and surveillance, but one of structural racism and bias; if you’re not already familiar with it, then Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru’s Gender Shades is a useful place to start understanding why facial recognition should not become the new normal for public life.

Anyway, this is what I meant to say in my talk.

Just because you can…

I’m going to start with what I tend to think of as the Jurassic Park Precept: “Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should.” However, I just looked it up and Ian Malcolm, the chaos theory expert in the films, actually says something slightly different:

My focus here is on some of the specific challenges brought about by general purpose AI in the context of war, conflict, and increasing global uncertainty.

The problem at the heart of this is definitely not rocket science: it’s the fact that irresponsible technology development has become the norm - and that doing things because you can, because they are interesting and possible, has become valorised as “innovation”. As I’ve said hundreds of times before, solving this is a social problem not just a technical or a legal challenge.

While I am generally a great fan of regulatory measures, they will not be enough over the coming decade. We also need a whole-society sense of urgency around re-establishing the social contract between technology developers and the rest of the world. As well as politicians and legislators, there needs to be action from communities, from tech workers, from corporate boards and shareholders. This is not a job for legislators alone, and we cannot rely on a sense of corporate responsibility or vague moral purpose to contain corporate ambition.

There is a lot to cover and I want to keep this short, so I’m going to start by very briefly breaking down some terminology.

What does “AI ethics” mean, anyway?

“AI ethics” is one of my least favourite phrases, because it brings together two incredibly wide-ranging, intimidating and complex topics in a very general and inaccessible way.

“AI” is an umbrella term for a diverse set of technologies that can do everything from adding cat filters to your photos to rapidly generating bombing targets. In 2022, Georgetown Privacy Centre announced it would deprecate the term “AI” in favour of more specific language, including describing underlying technologies being used. This very laudable step has not been followed more generally, but I recommend the next time you feel the need to say “AI”, it’s worth stopping and breaking down the term. Specificity makes things much less scary.

“Ethics” can also be a slippery concept when we’re talking about technology development. There is a common assumption that “ethical” behaviours are universal and pre-defined, when in practice they can be contextual and subjective. For instance, the professional code of ethics you adhere to may be different to your personal ethics, which may in turn be influenced by a range of factors, from religion to politics to lived experience.

Because this is a short talk, however, we won’t have time to address the entire field of moral philosophy and how it interfaces with the rule of law and the social contract. Instead I’m going to make this more specific and say: is it possible for general purpose AI to do no harm?

What is general purpose AI?

The European AI Act defines general purpose AI as:

AI systems that have a wide range of possible uses, both intended and unintended by the developers. They can be applied to many different tasks in various fields, often without substantial modification and fine-tuning.

General purpose AI takes the form of tools that can be used for many things. They exist to facilitate, not impede, unintended consequences and to be used and repurposed in all kinds of ways. Currently they are made by a few big companies, including but not limited to Google, Microsoft, OpenAI, and Palantir, and reused in consumer, corporate and government contexts.

Until now, social media has probably been the most prevalent general purpose technology of the digital age: what in the early 2000s was described as “user-generated content” has since created profound shifts in human relationships, work, media distribution, education and democracy. Facebook, which began as a “hot or not” tool for Harvard students, now has more than 3 billion active users, and facilitates social relationships between people all over the world.

Many of the consumer generative AI products on the market at the moment are comparable to social media platforms in their flexibility and openness. Tools such as Chat-GPT and Bard are, quite literally, made to learn and flex according to need. And - as we have seen this week, with the viral Taylor Swift images on Twitter - those needs often do not align with humanity’s higher purpose. As they stand, these particular tools are designed to be unmoderatable.

Context

In order for us to consider whether general purpose AI can do no harm, we next have to consider the global context that we’re operating in.

Again, this is a short talk, so we don’t have time to review the entire state of global relations, but - from the perspective of early 2024 - it seems likely that we are at the beginning, rather than the end, of a rising tide of conflict and uncertainty. The UK Government Integrated Review Refresh, published almost a year ago, states:

the transition into a multipolar, fragmented and contested world has happened more quickly and definitively than anticipated. We are now in a period of heightened risk and volatility that is likely to last beyond the 2030s.

I’m writing this on Friday, just as Israel’s national security minister tweeted “Hague Schmague” in response to the International Court of Justice’s order that Israel must take all measures to refrain from genocide in Gaza. Meanwhile, a Ukrainian drone operator told The Guardian this week that the extensive use of unmanned aerial vehicles (drones) by Russia and the Ukraine is ‘a kind of warfare that makes traditional Nato doctrine “pretty much obsolete”’.

It does not seem likely we are entering into a period in which multilateral AI governance agreements will hold much sway.

Technology adaptation and development

Any reader of the Ancient Greek epics will know that the pursuit of military advantage has been a forcing function for technological development throughout history. The pursuit of power and dominion, alongside struggle and resistance, are all great spurs to innovation.

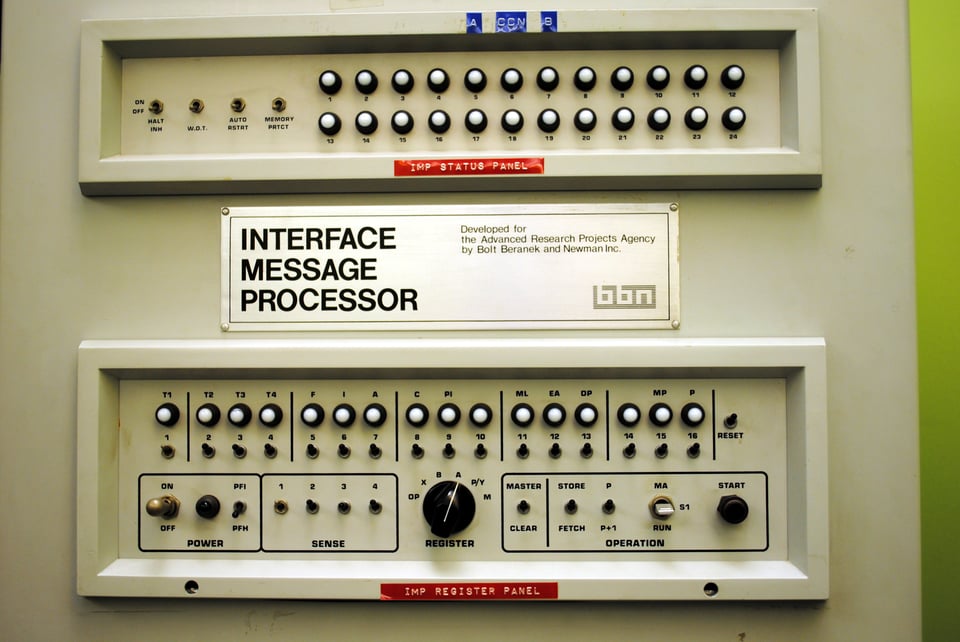

Many of the technologies we take for granted have intimate relationships with formal defence experimentation. During the Cold War, the US Defense Department invested heavily in the formation of Silicon Valley and ARPANET laid the foundations for the creation of the Internet. In the present day, the development of gaming technologies such as spatial computing are expedited by their military applications, and real-time data platforms do not only improve efficiency in the corporate sector - they are also deployed by personnel at the front line. The boundaries between defence, consumer and workplace technologies are intentionally blurred – and in times of warfare they risk disappearing altogether, as everything becomes a weapon.

GPS is a military technology that has been adapted for day-to-day maps and navigation - last year, GoogleMaps was suspended in Ukraine as it was inadvertently showing busy locations. In Gaza, communications networks and Internet access are in shut down, leaving people with little or no information, and unable to contact their loved ones. In times of conflict, social media’s ability to platform disinformation and deep fakes and sow division is also magnified and exacerbated. And while someone in the UK might use TikTok or YouTube to work out how to fix their washing machine, someone in a conflict zone might be using it to work out how to sequester a tank.

Technologies that might seem banal in times of peace are already being intensified and adapted in conflict. In the context of an increasingly VUCA world, it will not be possible to anticipate every outcome or deployment of technologies that exist to flex and learn.

Can general purpose AI do no harm?

At the moment, no.

General purpose AI is optimised for adaptation; this means it is relatively easy to weaponise in war and conflict scenarios. If - or, perhaps, as - conflict becomes more prevalent over the next decade, it seems unlikely that legislators and multilateral bodies will be able to move fast enough to enshrine binding international laws or treaties before widespread harms have played out at scale. Restricting and anticipating misuse and adaptations of general-purpose technologies needs to occur at multiple pace layers. It needs to become not just illegal but socially unacceptable to create harmful technologies without any regard for how they might be used.

Of course, the real issue here is the development of a culture in which it has become normal for some technologists and technology companies to ignore the basics of tenets of being a moral and responsible human being. While it should not be everyone else’s job to teach technology companies civics, there is an urgent need to re-establish some basic social norms so that we can move on and more people can get on with shaping beneficial societies. The longer we leave it, the harder this will get.

Which brings me to community

This is where people matter. The campaigners, the marchers, the unionising workers, the strikers, the organisers, the activists, and the people spinning up alternative infrastructures to show how it could and should be done. (A special mention here must go to Mirna El Helbawi who organises eSims for Gaza, distributing sim cards to connect families in Gaza to the outside world.)

The harms caused by technologies are difficult enough to spot in times of peace and stability because they (a) can be diffuse and (b) tend to initially affect the lives of people who are under-represented in power. In warfare, these harms risk being further masked by other atrocities.

I’ve written a lot recently about the role of communities in sensing and mitigating harms - the important work of horizon scanning, resisting, and seeking redress, and collective efforts to uphold justice, build new infrastructures, provide informal networks, and generally create the multiple essential points of friction that enable societal change. (In the unlikely event you’ve missed me going on about it, you can read more here and here.) This social organisation becomes even more urgent in the context of global volatility, when anticipatory action becomes essential.

It is vital for industry and governments to realise algorithmic audits are not going to solve social and civic issues of power and responsibility - after all, debiasing an algorithm or diversifying a data set will not redeem a product or a feature that quite simply should not exist. Boards, business leaders, and product teams all need to get better at saying no to harmful ideas; and - like it or not - the rest of us need to lend them the courage to do so.

While brokerage and international accords are important, the fundamental problem is that we also need the tech industry to grow up and develop a sense of moral responsibility. Politicians and investors also need to stop enabling a culture in which technologies that can easily be turned into grenades are labelled “innovation”. Social responsibility does not simply entail crying “existential risk”; it also requires the hard work to put proper processes in place.

This weekend, Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella appeared on NBC News to talk about guardrails and legal processes in the wake of the Taylor Swift debacle. Decent anticipatory precautions should have been in place long before the most famous woman in the world turned Microsoft AI tools into a bad news story.

To conclude, as global volatility increases, creating more technologies that can lead to unknowable outcomes creates unacceptable levels of risk.

All emerging technologies, not just AI, need strong anticipatory governance frameworks and clear mechanisms for limiting use and purpose built in from the very beginning. It is not the existential risks that AI may or may not create that concerns me; it’s how the tools we already have could be weaponised without restraint.

Some links and references

As mentioned above, you can buy sims for the eSims for Gaza project here (thanks to my colleagues Dominique Barron and Tom McGrath for sharing this). There is also a Tech for Palestine group/Discord.

The Taylor Swift story was broken by 404 Media, who have just opened a subscription model. Support independent media.

I’ve brushed over a lot of different things there, but if you’re interested in the relationship between D/ARPA and Silicon Valley, I highly recommend Sharon Weinberger’s The Imagineers of War and Margaret O’Mara’s The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America

If you work in tech and are interested in joining a union, there quite are a few options to explore, including Prospect, United Tech and Allied Workers, The Workers Union, Communications Union, Unite.

Also thanks to Sahdya Darr for the introduction to the Young Pugwash