I'm looking for a man in AI, trust fund, 6 foot, blue eyes

On Monday morning, along with a couple of thousand other people, I received an email with details of a secret location, a personalised QR code, and an admonishment to remember my photo ID.

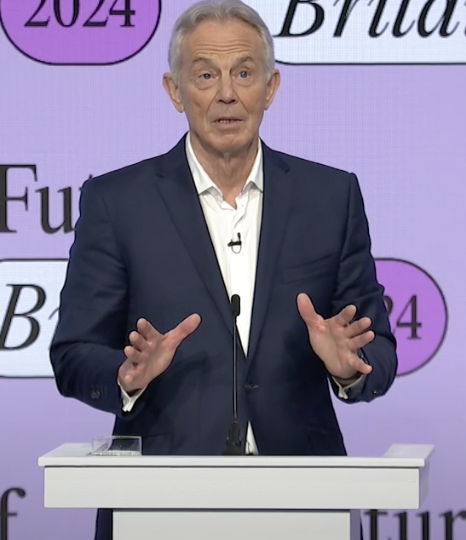

This wasn't an invitation to a rave on a private island, but joining instructions for the next day's Tony Blair Institute for Global Change Future of Britain Conference 2024: Governing in the Age of AI -- the only event this week to feature both Lord William Hague, former leader of the Conservative Party, and will.i.am, former member of the Black Eyed Peas, two avatars of 90s modernity who had, somehow, made it unscathed to the present day.

Holding this event on the fifth day of the new Labour government was certainly a flex -- one mostly designed to show off the kind of power and money that do-gooders like me rarely get to glimpse. From the non-compostable goodie bags to the Westminster ball room to the many many security guards, whose bag searches left no tampon unturned, to the bespoke noodle bowls and cameras that careened above the audience's heads, this was the big league, designed to sell in Blair's verve and enthusiasm for AI and big tech in all its glory. The secret location drop meant I couldn't book childcare in advance, so I arrived a little late, but as I queued for a free barista coffee to drink from a complimentary Tony keep cup I spotted the UK boss of Google, a former Conservative Science and Minister, and Jack Straw all milling around in the foyer, inhaling the oxygen of AI enthusiasm. The gang was all here, ready for the Future.

The first lesson of the day was that technology is difficult to deliver. Mic packs kept failing, the WiFi creaked, and will.i.am's demonstration of "AI banter" was scuppered by the firewall.

The second was that Blair’s vision for AI is one of naive wonderment rather than practical, hands-on knowledge. I didn’t see the whole event but I did watch him speak at least three times and heard him falter a few times as he relayed his memorised lines, wistfully observing again and again that “the world is changing so fast” and “few people know what they’re talking about”. He asked DeepMind founder Demis Hassabis, “If you were a government today why would you not want to have all of your data in a cloud-based infrastructure so you can analyse it with an LLM?”, a question that even Hassabis had to swerve, no doubt mindful of the security and accuracy implications of such a move and the enormous amount of data cleaning, infrastructure management and optimisation that would be required.

While Blair spoke of harnessing “the world’s wisdom”, Hassabis more cautiously mentioned that, while AI was good at playing games, it was currently “not even at cat intelligence”. Blair’s eyes widened as he discussed building an entirely new infrastructure for the NHS, but there was no indicator of where the money or skills to build such a thing would be found. By contrast, new Health Secretary Wes Streeting spoke in quite measured terms of the need for more MRI scanners to bring down waiting times so people could receive essential care, and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster Pat McFadden cautioned against “throwing white papers over the wall” as a method of innovation — perhaps a reference to Blair’s clarion call for reforming DWP, published earlier that morning.

The Tony Blair Institute’s vision of a rebuilt digital state is one of centralisation and management grip, what former Indian State Minister Rajeev Chandrasekhar described as “deliver[ing] government to citizens without leakage”, a fully automated vision of administration unbothered by the realities of everyday life or the exigencies of digital transformation. Blair and Hague sat side by side, like a digital state version of Statler and Waldorf, reminiscing about the Civil Service’s Sir Humphrey-like tendencies to kick things down the line, whereas McFadden referenced “not beating up the Civil Service” and testing and learning.

Where any of this sits with DSIT’s intention for public services to become more “personalised, convenient, and timesaving” is not yet clear, but if there’s a hopeful glimmer it’s that the intention of the new government might be to deliver services that work for the public, rather than for heroic former Prime Ministers. Technological progress happens in tandem with societal change; as my colleague Anna Dent set out yesterday in Computer Weekly, public trust is essential to deliver this well -- particularly for a government with such a wide and shallow mandate.

My conclusion from yesterday is that TBI’s approach to technology is happening at a remove from the reality of modern politics and the inconvenience of delivery; that its techno-optimism is out of step with the managed caution of the new government. And while Larry Ellison’s money might be sufficient to keep an audience of think tankers and former MPs in tote bags, it is not yet enough to wave a digital magic wand.