Finding Satisfaction in the Process

On enjoying the creative process, and my 2024 creative highlights.

Wellspring: Issue 2

Howdy, Folks :)

Welcome to the second issue of Wellspring. In this edition I'll be covering the thorny idea of "productivity" and how we need to focus more on the humanizing idea of process. I'll also be reviewing my creative highlights of 2024 (ie, my favorite books, film, and TV of the past year). So, let's get started!

Can't Get No Satisfaction

Back in November of 2024, I reposted a skeet by Mary Robinette Kowal. She'd written: "What if, instead of trying to have a productive writing day, you aimed for a satisfying one instead?"

In my repost, I wrote:

“Productivity” is a capitalistic measure of success. Art is, at its grubby heart, supposed to be anti-capitalist. We know this because it predates capitalism (prehistoric cave paintings, anyone?). So forget capitalist measures of success for writing. Seek something sustainable -- like satisfaction.

That is, in a nutshell, what I'm expanding on in this newsletter.

"Productivity" Defined

If you do a simple Google search for "productivity", what you'll pull up is a plethora of sites explaining the economics of production and productivity. According to the Investopedia, "productivity" is "a measure of performance that compares the output of a product with the input, or resources, required to produce it".

Applying this definition to writing and creativity specifically, we can see things going pear-shaped pretty quickly.

If we consider the output of creative writing to simply be the words on a page, then input becomes the time and energy expended to create those words. But time and energy varies hugely across genres, mediums, projects, and writers.

Let's take, for instance, Writer A. Writing 1,000 words in a single two-hour session is a piece of cake for this writer. On the other hand, there's Writer B. For Writer B, 1,000 words might happen in a week, or even a month, of broken up sessions. Who's to say who's the more "productive" writer? On paper Writer A seems more efficient, but, Writer A could be a novelist whereas Writer B could be a poet of haikus -- which has a huge effect on the landscape of "productivity". 1,000 words of haikus, in a month, could be seen as an enormous output.

It could also be that, for Writer A, those 1,000 words are a first draft, which inevitably means that those words will be in worse shape than a second, third, or final draft. Does this mean those words have any less value, however? Absolutely not. Even if all 1,000 of those words don't see the light of publication, they still had value in that they helped the author get from a blank page to a finished product.

So, you see, measuring "productivity" as a writer is not necessarily a simple capitalistic equation of output divided by input. Rather than relying on the notion of "productivity" to define writerly success, what we should focus on instead is the fact that the creative process is inherently nuanced, and, well, a process, first and foremost.

Pure Imagination and Process

Because creative writing is a process, it is also deeply grounding and humanizing.

You can't push a button and create Hamlet or Pride and Prejudice. These works came into being through a process which required time, effort, dedication, play, and imagination.

Imagination is key, as it is the thing, I think, which often defines our humanity. It is through imagination that we, as a species, came to speak and develop language to communicate complex concepts with one another. It is through imagination that we took to wandering the entire world. It is through imagination that we created gorgeous prehistoric rock carvings and cave art in the Paleolithic.

All of these accomplishments -- language, travel, and art -- are not merely products of the imagination, however; they are processes or part of a process as well. One does not learn how to speak or write automatically, but through a process. Similarly, languages undergo changes through time that are part of a process. Travel is a process by which you deliberately make choices to leave where you are and go elsewhere. These days it requires research, sometimes plane tickets or car rentals, packing, and etc. Art doesn't happen instantly, but takes time to learn technique, how to use materials, and etc.

Thus, it could be said that the process itself is also deeply humanizing. It is the forge through which we form and refine ideas of the imagination.

(As an aside: this is why generative AI, such as ChatGPT, will never create "art". It skips the entire process by which art is accomplished, and, has no imagination to speak of.)

Rules and Restrictions

Imagination and the process of using imagination is something which doesn't come with a definitive product, at least, not the kind that capitalism inherently values. And what capitalism values is something you can make money off of.

Language is ingenious, but it the English language, for instance, with its irregular verbs and contradictory grammatical rules, cannot be said to be the most efficient product in and of itself.

Similarly, art is not necessary a great "product". If we take one look at Picasso's staggering work, Guernica, it immediately overwhelms us, reminding us of the atrocities of war. As far as products go, a painting that is not at all pleasant seems like a no-sell. (Nevermind that that's its genius.)

Imagination and its fruits, creativity, are inherently anti-capitalist not only because they far predate capitalism, but also because the "products" of imagination are not necessarily easy to package up and sell at a tidy profit.

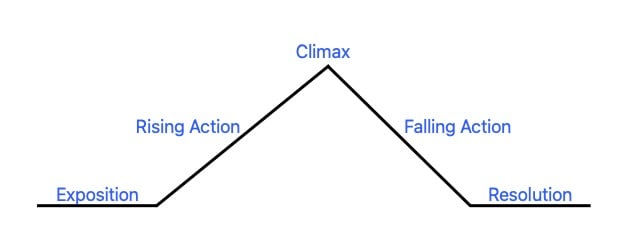

Sure, people try to sell imagination and creativity, usually by placing certain restrictions, which is the antithesis of how imagination works. The contemporary fiction industry in the U.S. is a prime example. In the rush to commercialize fiction and make a profit, the publishing industry has imposed certain rules which define what will make a work "commercially successful". Usually a work of fiction should follow arbitrary rules defined by genre (science fiction, fantasy, thriller, mystery, romance, etc.). There are additional restrictions in terms of plot structure, that is, most "commercially successful" fiction must follow the basic plot arc of "exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution". Lastly, debut fiction novels should also adhere to certain word counts, with 90,000 words being ideal for a work of contemporary literary fiction.

In today's publishing market, works that follow these prescriptive formulas are often pushed over works that are challenging, thoughtful, or innovative. There are places which truly imaginative works can thrive, such as small presses and in poetry. Yet, the market for a book like James Joyce's Ulysses, which fundamentally altered and challenged the structure of the novel, doesn't really exist with the traditional publishing industry. I would venture to say that great works like Ulysses would never see the light of publication if they were pitched for the present-day fiction market. That's how restrictive and unimaginative mainstream traditional publishing has become. It's profit-driven, rather than creativity and imagination driven.

Finding Satisfaction

This is where satisfaction based on process rather than product is crucial towards maintaining a positive creative life as a writer.

If imagination is a process, rather than a product, it makes no sense to judge our progress as writers on the basis of a product, or a capitalistic notion of productivity. That is, if we get too caught up in product and productivity as outputs, then our input will suffer. Input being the very things we need to create -- chiefly imagination.

I'm as guilty of using word counts, for instance, as prime evidence for my "productivity" as a writer. I do keep track of my word count throughout the year, for example, and of course I monitor word count in my manuscripts. It's a reality of the contemporary fiction market that word count matters.

I'm also guilty of using publication as evidence of my writerly "productivity". I see consistent publication as part and parcel of a writer's career. When I don't have something published after about a year or two, I start to feel anxious, like my writerly resume will have a gap.

But over the past year, I've found my definition of "productivity" as a writer shifting. I no longer consider it a "bad" writing day if I don't manage to get some words down on page. There are so many ways to write and be "productive" -- nay, imaginative and creative -- and word count is simply one aspect of that. You can spend a whole day brainstorming and outlining. You could use your writing time to research some plot points. Even taking a walk and daydreaming counts as writing, because it allows your mind and imagination to run free. Sometimes resting is necessary to the writing process as well, and having a much-needed break is more important than spitting out some more words.

In a nutshell, the older (and hopefully wiser) I get, the more I cherish writing as a process, rather than a product. I do value product to a degree. I won't lie and say that I don't appreciate the current draft of my YA novel, The Weight of the Impossible, because it's a pretty fine final draft if I do say so. But that finished product was the result of a years-long process I engaged in with my imagination to create something I consider worthwhile. And I think more creatives would find deeper satisfaction with their work if they shifted from worrying so much about the product and focused simply on process.

2024 Creative Highlights

2024 was a fantastic year for discovering innovative and boundary-shattering stories for me. The best books, TV shows, and films of my 2024 are as follows:

Best fiction book: The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro (honorable mention for his more recent novel, Never Let Me Go, which is almost equally as heartbreaking).

Best nonfiction book: Dark Nights of the Soul by Thomas Moore. A beautiful, soothing meditation on dealing with tough times in life.

Best TV series that I'd previously watched: Interview with the Vampire season 2. This season was immensely impressive and satisfying on multiple levels.

Best TV series that was new to me: Tale of the Nine-Tailed. A Korean supernatural thriller romantasy series, Tale of the Nine-Tailed follows the adventures of a nine-tailed fox who searches for the reincarnation of his long-lost love. When he finally finds her, things do not go entirely as expected.

Best film: All of Us Strangers. A haunting, elegant, and comforting meditation on grief, loss, and what it means to be a gay man in the modern world. Lovely film, easily my favorite film of all time.

On the personal front, my own creative highlight was polishing the final draft of my YA novel, The Weight of the Impossible, and prepping it to query for agents in 2025. It's been a wild ride since I started writing the book in 2018, and I'm so proud of this story. I can't wait to query agents and hopefully find someone who is just as crazy about the novel as I am to represent it. More than that, I'm anxious to get the novel published and out into the world. So, I'm crossing my fingers and toes that this comes to pass soon enough.

In future issues of Wellspring, I'll be teasing excerpts of The Weight of the Impossible, so you definitely have that to look forward to this year.

Here's to the New Year. I hope you have a bright and beautiful year ahead of you. I will "see" you in your inbox again in March!