Going Out, October 2025

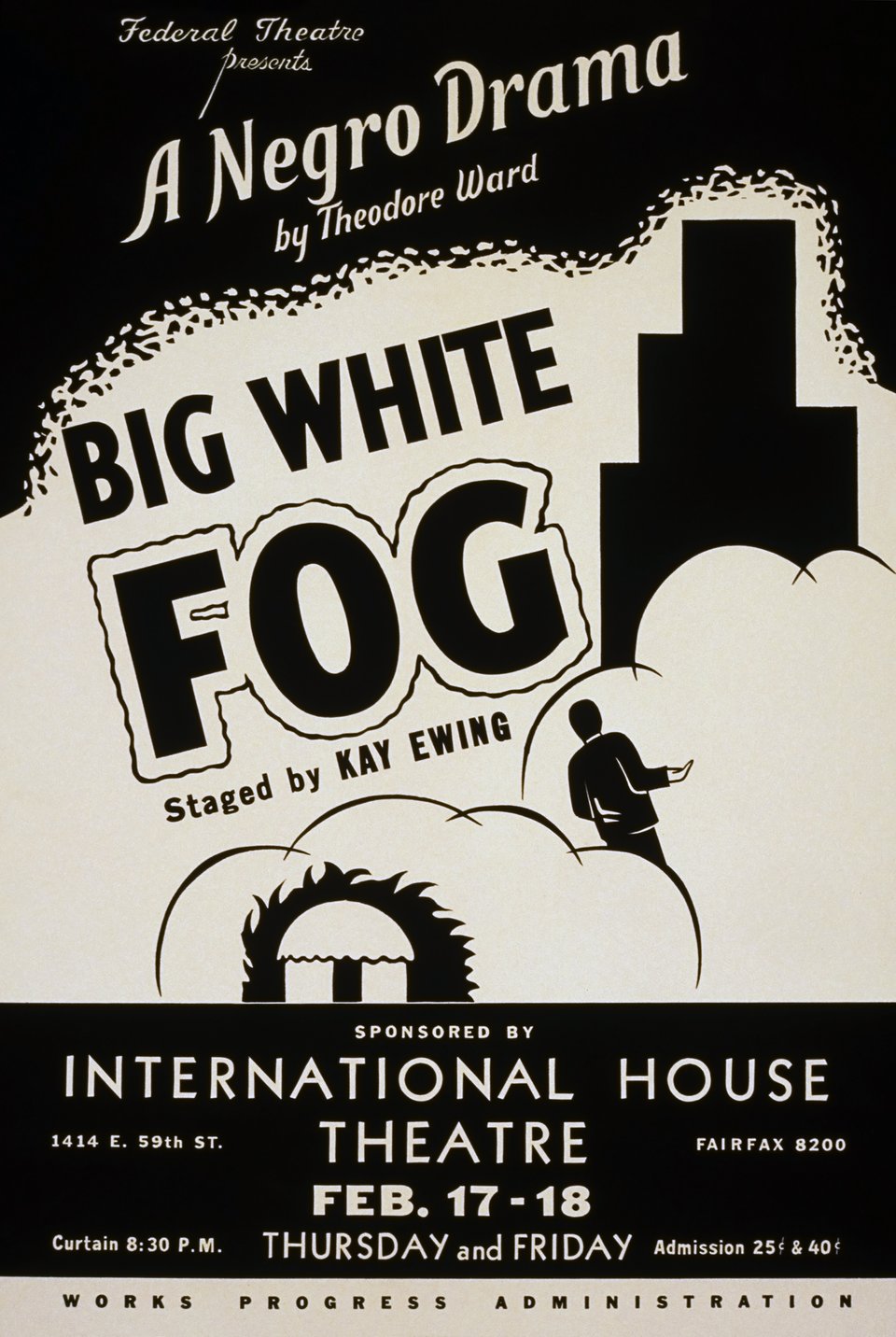

Two Sundays ago, while scrolling through TikTok (an activity I try to limit to weekends, both for standard mental-nutritional reasons and because my algorithm seems to be much more unpleasant during the week), I ran across a young woman I don’t remember ever seeing before, but because the algorithm has discerned that I’m usually interested in what Black Chicagoans have to say, her video recommending two plays currently running in Chicago was indeed precisely targeted. The new comedy-drama Ashland Avenue, starring Jenna Fischer, was less interesting (both to her and me), but the Chicago Renaissance classic Big White Fog, originally staged in 1938, caught my attention, especially as I wasn’t familiar with it; I tend to be pretty confident in my knowledge of the twentieth-century canon, and when something I don’t already have a mental pigeonhole for crosses my path, it’s immediately intriguing.

After skimming the play’s Wikipedia article the next day, I bought a ticket, choosing an October date in order to satisfy the see-one-show-a-month remit of this series. I was a little chagrined that the ticket cost more than twice as much as it had to see Carmen at the Lyric Opera, but once I made the hour-and-a-half train and bus journey from Rogers Park to the University of Chicago and found my seat in the Court Theatre, I was immediately reconciled to it. The Lyric is a vast space, and I’d been way up on the top balcony, peering down to glimpse only the broadest gestures of the ballet; the Court is small and intimate, the actors only feet away from the audience, with no curtain: as the crowd found our seats, the single set was already there on stage, a middle-class living room in 1922, period jazz playing on the sound system (I know I heard Louis Armstrong, Johnny Dodds, and Sidney Bechet, although I didn’t immediately recognize the records) while we reviewed the program via QR code on our phones.

Big White Fog, written by Theodore Ward in 1937, is a chamber drama narrating the history of a striving Black family on the South Side of Chicago over the course of ten years, from the violence following World War I to the immiseration of the Depression. The Marcus Garvey movement of the early Twenties, which raised money from penny-saving Black Americans across the country for a scheme of African repatriation-slash-recolonization plainly modeled after early Zionism, plays a significant role in the narrative; I was grateful that my miscellaneous education allowed me to catch just about every cultural reference made in the 88-year-old script, which assumes a level of familiarity with the period entirely appropriate to 1937, but doesn’t handhold a modern audience. The central ideological struggle of the play is between Garveyism (representative of an early strain of Black Nationalism), as personified by proud Tuskeegee graduate turned manual laborer Vic Mason, and Black capitalism, argued for by his wife’s brother-in-law Dan Rogers, a Pullman porter who opens a kitchenette, parlays that into becoming a landlord, then a slumlord, and ends in the depth of the Depression looking the other way while his wife runs their property as a squalid cathouse. Meanwhile Vic’s son Les, whose dreams of a college scholarship are dashed when the committee learns he is Black, self-educates into Socialism and joins the argument from the left as he grows up over the course of the play.

But while the men of the household argue ideology — all except Vic’s brother Percy, a veteran of the War and victim of the white supremacist violence immediately following it, who copes with liquor and cynicism — the women go about the thankless work of keeping a roof over their heads and shoes on their feet. The men may get the biggest speeches and most intense emotional outbursts, but the women of the cast carry the bulk of the plot, and have their own ideological divisions too — initially the sisters Ella and Juanita serve only as a proxy for the divide between their husbands Vic and Dan, but eventually, as finances go from bad to worse, the divide between sexual respectability (Ella and her mother Martha) and practicality (Juanita and Ella’s daughter Wanda) widens, as do the even more painful divisions of colorism: Martha is endlessly proud of her (white) Dupree blood, and looks down on the fully black Vic. But none of the characters are mere ideological signifiers: Ward invests them all with the full complement of human frailty and dignity, with enough domestic downtime, shot through with humor, in between the shouting matches that you get keenly interested in all the doings of the Masons and their broader relations, so that when the pressures of the outside world come home to roost it hits all the harder.

The cast I saw on Saturday was excellent; perhaps a little wobbly on the younger end of the company, but the principals, particularly Joshua L. Green and Sharriese Hamilton as Victor and Ella (the emotional centers of the play), Amir Abdullah as Dan (who has the thankless task of making the ideological arguments feel lived-in), and Greta Oglesby as Martha (who got, and deserved, the bulk of the audience’s laughs), were genuinely astonishing, investing Ward’s period characters with just enough contemporary vividness to make their varied heartache, anger, and hopefulness immediately relatable without slipping into anachronism. I could occasionally have wished for a little slower pacing, just in order to catch my breath — their familiarity with the material, after four weeks of shows, was obvious — but director Ron OJ Parson’s staging was fluid and naturalistic. The large cast — one legacy of the play’s origins in the Federal Theatre Project, with the aim of providing work to as many artists as possible — managed its manifold entrances and exits, overlapping dialogue, and occasionally busy blocking so consummately that it felt at times like watching a really slick sitcom, only more electric because everyone was right there.

It must have been some twenty years since I last saw a serious play in the theater — musicals and comedy shows were generally the only things that ever got me out of the house before I started my current program of seeing a show a month come hell or high water, and even they were rare — and there really is nothing like it. I’ve known intellectually, of course, that Chicago is one of the great theater cities of the world, but living here for twelve years before I saw any world-class theater is borderline immoral. I have so much to catch up on.

I already know what I’m seeing in November, and I don’t know whether I’ll be able to get a whole newsletter out of it. We’ll see when it happens, I guess. Talk to you then, if not sooner.