Exist Yesterday: #Let5D0It, Week Three

No idea whether anyone is actually getting, let alone reading, these, but I’m continuing to resend my blurbs on “favorite singles 1954-1976” from my blog.

36. Alton Ellis, “I’m Still in Love” (1967)

(Ellis) prod. Coxsone Dodd

Studio One 3022 | did not chart

“And I don’t know why-hy-hyyy, my baby”

I still feel very much like an arriviste to reggae and its forebears and descendants, and I think it’s right and proper that I do: because so much of the rest of my education in 50s-70s pop was carried out by paying attention to the radio and scavenging among the used CDs and LPs in secondhand shops in Phoenix, the knowledge that there are places in the world where Jamaican music is part of the normal fabric of pop rather than an expensive import or specialty “world-music” scene keeps me from feeling like I’ve ever been able to get my arms around the totality of it: it’s just not in the air where I have lived in the same way as it is in the UK, or even in diasporic hubs like New York City. So my rocksteady knowledge has always been relatively skeletal, outlined more by popular covers than by the originals. That said… the winsome ache in this single has meant more to me over almost twenty years than a whole host of music that was produced closer to home and demographic cohort. Alton Ellis’s high, fragile croon; the echoey musical space that envelops him, making the record sound haunted by the ghosts of desire and longing; the sheer plaintive basicness of the lyrics, making it sound all the more like a desperate plea from a man’s soul rather than a constructed piece of pop artifice — these have clung close to me in ways that I couldn’t have described or even recognized for many years. And of course it’s still a magnificently constructed piece of pop artifice, just following different rules than the North American ones I was used to.

First encounter: That Pitchfork list of the 200 Best Songs of the 60s, which I’ve referenced several times already and will no doubt reference several times more. It was a galvanic experience for me, kickstarting my desire to systematize music history rather than paddling around at relative random in the waters of the past I had waded my way into. The week the list came out, I downloaded every song on it from someone on Soulseek who had already made a folder and listened through it in countdown order: “I’m Still in Love” was in the bottom 10 of the list, which meant it was one of the first new-to-me songs that I heard, and might have been my first encounter with 60s rocksteady at all, not counting covers. And, well, you never forget your first.

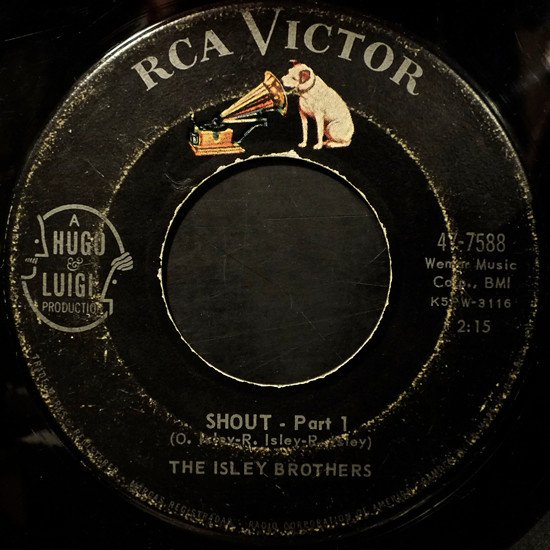

35. The Isley Brothers, “Shout” (1959)

(Isley/Isley/Isley) prod. Hugo Peretti, Luigi Creatore

RCA Victor 7588 | #47 US, #43 UK

“You’ve been so good to me baby, better than I’ve been to myself”

The perpetually underrated Isleys have been at or near the center of just about every twist and turn in the last sixty years of black music history, and if their contributions all too often get boiled down to their early barnstorming R&B — which is comparable to ignoring James Brown after “Please, Please, Please” or Etta James after “Tough Lover” — it’s a testament to just how barnstorming it was. The double-sided single “Shout - Part 1” b/w “Shout - Part 2” (long since collapsed into a single unit by digital forms of media storage, let alone long-playing records) is among the longest songs on this list, even factoring in the excesses of the 70s, because the Isleys’ expansive, gospel-bred vision of passion, build, release, and ecstasy could not be condensed into the abbreviated runtime of a pop single. Like Ray Charles “What’d I Say” the same year — a near-miss for this list — “Shout” is a self-assured summation of the unrivaled power and confidence of black pop at the end of the 1950s, the decade in which black dance music — rhythm and blues, for the trade press — began evolving into so many new forms at once that bewildered white adults still looking to 40s icons like Nat King Cole and Peggy Lee to keep them abreast of the new trends in pop were tempted to write it all off as so much noise. But black adults saw an even direr threat in the Isleys’ secularization of sacred methods, and campaigns to keep “Shout” off the air were led by African-American church groups scandalized by traditional gospel energy, rhythm, dynamics, and even lyrics (see epigraph) being transferred from the worship of God the Father to the worship of a sexual partner. Remembering when she used to be nine years old, on the other hand — horrifying, but entirely uncontroversial at the time.

First encounter: It was in 1999, in the leadup to the turn of the millennium, that the simultaneous arrival of media-outlet lists of “greatest songs of the twentieth century” and Napster got me interested in sampling from a wide variety of music. Arts-coverage demographics being what they always are, those lists were heavy on Boomer classics and light on the music of the past twenty years, even lighter on music before 1954. I don’t remember which one pointed me in the direction of “Shout,” or if I stumbled across it a couple of years later looking for more Important Fifties Songs, but I recognized it from Sister Act and was thrilled by the rawness of the original. It quickly became a centerpiece in the image I was slowly forming of twentieth century musical history.

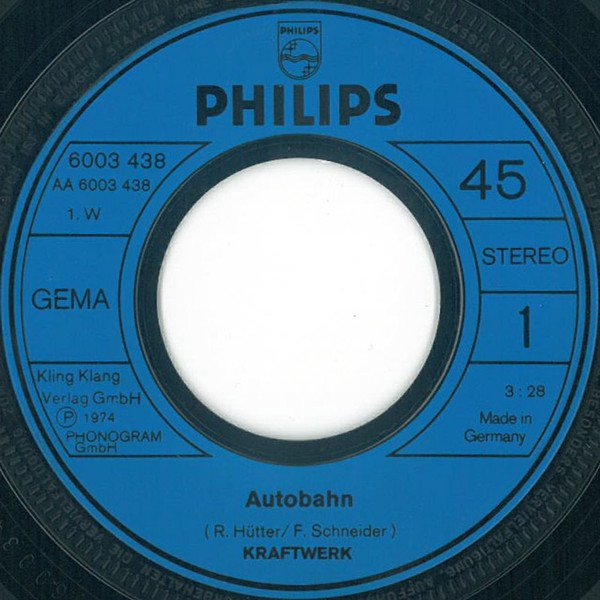

34. Kraftwerk, “Autobahn” (1974)

(Hütter/Schneider/Schult) prod. Conny Plank

Philips 6003438 | #25 US, #11 UK, #9 DE

“Wir fahr’n, fahr’n, fahr’n auf der Autobahn”

“Oh, but it shouldn’t be heard as a single,” say the dullest people in the world. “You need the full 20-minute LP version to get the real experience of the song.” Nonsense. Both (and in fact there are more than two) versions of the song as it was released in 1974 are excellent, and are doing different but complementary things, and only someone who doesn’t, in their heart, believe that pop music is as worthy as progressive music of whatever stripe (jazz, rock, techno, etc.) can believe otherwise. For my part, I will always favor pop values like concision and directness over prog values like experimental development and technical wizardry; I even favor the German (and US) edit of the single over the UK edit, which splices in some of the late-song whooshes from the full suite, unbalancing the three-minute structure and dispelling the calm sense of reverie that the original edit encourages. No German literalist will ever convince me that Ralf, Florian and the boys weren’t making a sly reference to a decade-old song also about the joys of driving, knowing what “fahr’n” (drivin’) sounds like to an Anglophone ear; and it’s that deadpan embrace of pop tradition even while inventing a solid-state future so far-flung that nobody could see it from 1974 but them that makes Kraftwerk one of the great pop acts of the 70s in addition to being among the most important experimental progressives of the twentieth century.

First encounter: The worst job I ever held, full of the cruelest and most cowardly people, was in the auto insurance industry; my only reprieve from the toxicity of the environment was that I could listen to music as I worked, and a lot of my mid-2000s musical education took place either at that desk or on the long drive to the office and back. I’d been familiar with Kraftwerk since the beginning of the decade, since even the skimmiest dip into twentieth-century music turned them up, but I dutifully listened through every album in order to dissociate from doing clerical work that would contribute to denying injured people the accident payouts they were entitled to. Only the most melodic pieces stuck with me: “Computer World, “Neon Lights,” “Trans-Europe Express,” “Radioactivity” — and the granddaddy of them all, the masterpiece that has the best claim to be considered the first true electropop song, “Autobahn.”

33. “Tennessee” Ernie Ford, “Sixteen Tons” (1955)

(Travis) prod. Lee Gillette

Capitol F3262 | #1 C&W, #1 US, #1 UK

“Muscle and blood and skin and bones, a mind that’s weak and a back that’s strong”

One thing I don’t think rock-centric models of twentieth century music appreciate enough is the fact that a massive crossover country hit with a prominent clarinet hook could only have been possible in the throw-anything-at-the-wall 1950s: after high fidelity recording had opened up the complete range of audio dynamic possibilities, but before practice and habit had reified genre barriers, for a little while there anything could be anything in pop, even a genial huckster with a pencil-thin mustache and a voice made for radio announcing. He grew up in Bristol, Tennessee, but studied classical music in Ohio before entering the Air Force towards the end of the War, and it was in while working in radio in Pasadena that he developed the “Tennessee Ernie” character, a hillbilly parody that eventually spun into television work as a kind of Southern California predecessor to Hee Haw. His recording career began in 1949, at the dawn of high-fidelity pop, and he sang western songs, country boogie, crossover pop, and pseudo-folk that did well on both country and pop charts, but it was this sparely-orchestrated cover of Merle Travis’s “Sixteen Tons,” originally released as a B-side to the gently swinging “You Don’t Have to Be a Baby to Cry”, that accidentally immortalized him when DJs started flipping the record. Travis’s original is probably better folk — indeed it was first released on his album Folk Songs of the Hills — but Ernie’s amused, half-kidding delivery is terrific pop, and the timelessly relatable sentiment of “another day older and deeper in debt” has given it legs far beyond the moment.

First encounter: I’m sure this was one of the first thousand mp3s I ever downloaded between 1999 and 2001 thanks to my initial scouring of twentieth-century best-ofs, and I’m equally sure it was among my least favorite when I did: it sounded hokey, awkward, and starchy, Ford’s trolling comedy performance at odds with the grit and heft of Travis’s lyrics. Now I understand the lyrics as equally trolling comedy, especially the hyperbolic tough-guy verses, which only underline the thrust of the chorus, reinforced by frequent appearances on bleeding-heart social media feeds: it doesn’t matter how toxically masculine you can get, you’re still at the mercy of capitalism.

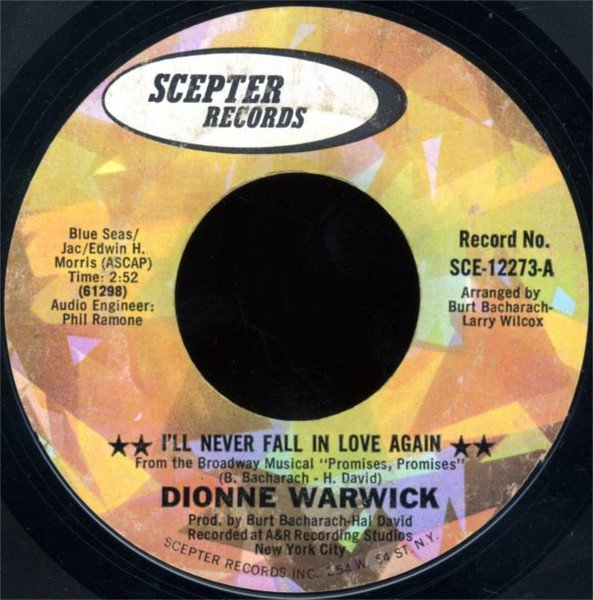

32. Dionne Warwick, “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again” (1969)

(Bacharach/David) prod. Bruce Bacharach, Hal David

Scepter 12273 | #1 EL, #8 US

“Don’t tell me what it’s all about”

Yes, yes, it’s the immaculate early ’60s Bacharach–David–Warwick collaborations that are most widely and justly celebrated, from “Don’t Make Me Over” to “Anyone Who Had a Heart” to “Walk on By.” By the tail end of the decade, with rock spinning into so many dizzyingly new forms and variations, the formula had surely been exhausted, and this could only be a nostalgic coo, an easy-listening retreat from the noise and urgencies of the present. Yeah, maybe. But you don’t always get to pick what your favorite is, and although mine frequently (even tediously!) line up with critical consensus, this is one I will stick to regardless. The first record in this list was a strike in the war against overdetermined periodization, and so is this: if it’s not the most perfect Bacharach–David–Warwick record, with some of the starkness of the early work sanded down to a more tranquil AM-pop gauze, it’s the one that has burrowed its way deepest into my sense of self. You only get lies and pain and sorrow, so for at least until tomorrow. I have never felt comfortable categorizing myself as asexual or aromantic — my sense of self tends more toward monastic than queer — but songs about the refusal of love have always spoken to me more personally than songs about the glory of it. And the catch in Dionne’s throat, worn tired from a decade of singing Bacharach and David’s half-sophisticated, half-pat songs about love and self-assurance, resonates with me too. I’ve felt old since my twenties, old and tired; and the pillowy orchestration over an equally throwback bossa nova beat, with Bacharachian trumpets more than ever resembling puffs of clouds, is just as soothing as Hal David’s cynical-but-actually-secretly-romantic lyric.

First encounter: Okay, so the White Stripes covered “I Just Don’t Know What to Do with Myself” on Elephant in 2003, which was the kick in the pants I needed to investigate Burt Bacharach, a name I vaguely knew from reading up on music but hadn’t zeroed in on before. I grabbed a bunch of random mp3s off of whatever service I was using at the time (Limewire, maybe?) and added them to the rotation without really looking deeply into the dates or circumstances around them, and “I’ll Never Fall in Love Again” quickly became my favorite. It wasn’t until later that I discovered it was late-period, establishment Bacharach–David (it was from a musical, it won a Grammy) rather than the work of hungry young artists establishing themselves.

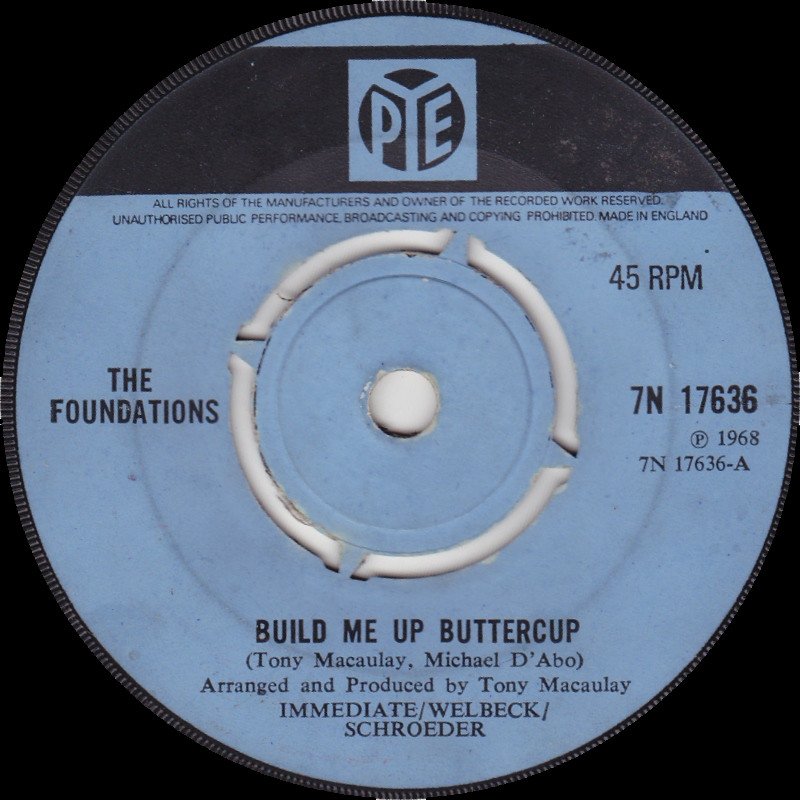

31. The Foundations, “Build Me Up Buttercup” (1968)

(Macaulay/D’Abo) prod. Tony Macaulay

Pye 7N-17636 | #3 US, #2 UK

“I’ll be home, I’ll be beside the phone waiting for you ooh-ooh ooh”

This is the last song I added to this list, a panicked substitute for the Equals’ “Police on My Back” once I realized that the latter only being released as a single in Germany, Austria and the Low Countries disqualified it from the overall poll project. I still think “Police on My Back” is great and urgent and looks forward to punk and two-tone in a way that basically nothing else in British pop did at the time; but I can’t be sorry for the change, because I’ve loved this song far deeper and longer. I suppose it was There’s Something About Mary that made the song briefly omnipresent around the turn of the millennium, but as I never saw the film it was always a pure radio experience for me, a shot of soulful sunshine pop that it took numerous visits to online repositories of knowledge to make stick in my head as a black British song — I had always heard Colin Young’s smiling growl as of a piece with the many white American acts straining after Southern soulfulness that surrounded it in the late 60s US charts (the Box Tops, the Rascals, the Buckinghams, the American Breed, Blood, Sweat & Tears, etc.) Sure, the rhythm section swung and bounced rather than stomping like all those white boys, but I couldn’t hear the R&B inflections because I was interpreting the soul as blue-eyed, and honestly the cheerful sound and playful lyrics had me bracketing it with chirpy Californians like the Association, the Turtles, or the Grass Roots. (Two of which I have loved dearly, and would be on this list if I wasn’t more concerned with covering a variety of genres; sunshine pop proper gets one entry besides this one.) But it wasn’t as wimpy as those bands sounded either, and the combination of heart-on-sleeve winsomeness and crisp punchiness, a serviceable imitation of Motown without the boiling drama, makes “Build Me Up Buttercup” a mood stabilizer almost as effective as nutrition, hydration, or sleep.

First encounter: I genuinely have no idea. I might have heard it as background music in public spaces in the 90s, or on oldies radio, or in advertisements; I do know that when I first paid attention to it in a “wait, I really like this song” way, I was already familiar with it. And since it received regular oldies play, I heard it relatively frequently, and never got tired of it. And even now, with vastly more listening experience under my belt, those lifting key changes still work, and I’m almost tempted to holler along in my workplace: “WHAH do you build me up?”

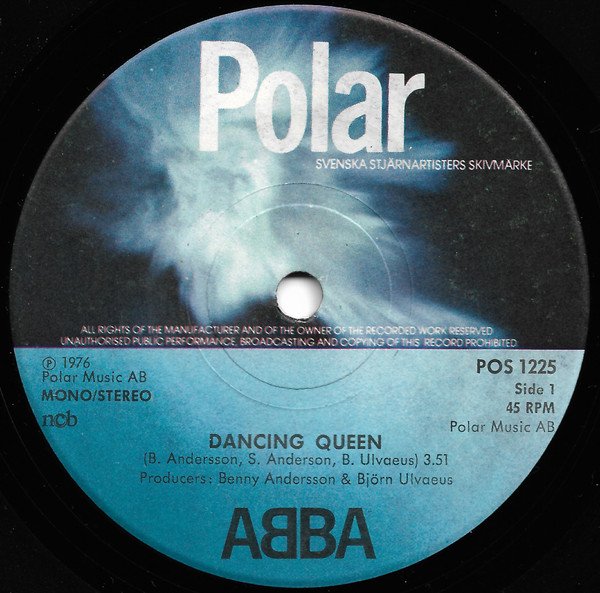

30. ABBA, “Dancing Queen” (1976)

(Andersson/Anderson/Ulvaeus) prod. Benny Andersson, Björn Ulvaeus

Polar 1225 | #1 US, #1 UK, #1 SW, #1 USSR, etc.

“Where they play the right music, getting in the swing”

This is the closest my list gets to disco: an outrage, considering how central disco (and more importantly the central premise of disco, which is that dancing is among the most critical functions of popular music) is to my conception of pop. But most of my favorite disco qua disco songs were released in 1977 — see here for most of them and a lot more besides — and more honestly, I came to an appreciation of disco relatively late in the decade I spent immersed in twentieth century music, and so less of it has had time to stick to my ribs. But that aside, it’s not like I need an excuse to appreciate “Dancing Queen,” one of the most fêted records of all time. Only acts like Elvis, the Beatles, Michael Jackson, and Céline Dion have come close to matching its global chart dominance during its season, and it has remained perennial in a way that they haven’t always. Everything everyone says about it — the blissed-out orchestration, the undercurrent of melancholy, the oddly slow tempo for a disco song, making it more a sympho-pop reverie about dancing than a dance song proper, the unidiomatic English that makes for more memorable and even immortal lyrics than a native speaker could have produced within the restrictions of an ESL vocabulary — is true, but none of that gets at why I, specifically, love it. Statistically, of course, I’m part of humanity, so the odds that I would fall into the very thick demographic slice of humanity that loves it are pretty high; and I’m happy to confess that a truculent, knuckle-dragging “fifty million fans can’t be wrong” mindset has helped me hear my way into some of the contemporary pop music that has given me as much joy and fulfillment as anything else in the past sixteen or so years. But the bald, embarrassing truth is that I’m just a sucker for songs about music, and “Dancing Queen” is one of the greatest songs about the transitory but real, so painfully, ecstatically real — if only for the night, the hour, the song — joys of music, especially when you are young and music is everything. The fact that I never was young when I knew this song, that it has always been colored with a faded nostalgic glow, Agnetha and Frida’s close-meshed harmonies a secular echo of the close-meshed harmonies I actually grew up listening to, only makes it all the sharper and more poignant: this whole world had vanished by the time I was old enough to know about it, and only the echoes etched onto recordings are left of it. Which was true of nearly all of the twentieth century’s music by the time I came to take an interest in it; which is another one of the reasons I’ve spent so much time there, trying to capture that golden glow.

First encounter: Like most people born after 1972 or so, I couldn’t tell you when I first heard it. I do know when I first paid close attention to it, though: 2005. I was participating in a message-board challenge to make a mix of great songs from the year of my birth. That message board was deeply rockist and hidebound (one prominent poster was a South African who venerated the Beatles and vocally despised African music), so it was with some glee that I boasted to the younger punk fans about being able to load my mix with 1977-era punk rock; and it was with some malice that I threw in “Dancing Queen” (not having fully done my research about single vs. album release) to show how broad-minded I was. I listened to that mix a lot; and especially sandwiched between “Blank Generation” and “Police and Thieves”, “Dancing Queen” sounded epochal, heroic, almost sacred: a cathedral of calm and beauty and sensitivity in between all the snarling, posturing young men. It still sounds that way in the playlist I’ve been listening to more recently, sandwiched in between “Police on My Back” or more recently “Build Me Up Buttercup” and — well, wait till tomorrow.

Next week: #29-23, featuring a few more idiosyncratic choices than previously.