Exist Yesterday: #Let5D0It, Week Six

Resending my blurbs on “favorite singles 1954-1976” from my blog, coming to you late after an impromptu family vacation messed up my routine. Week Seven, the finale, should be back to the normal Monday schedule.

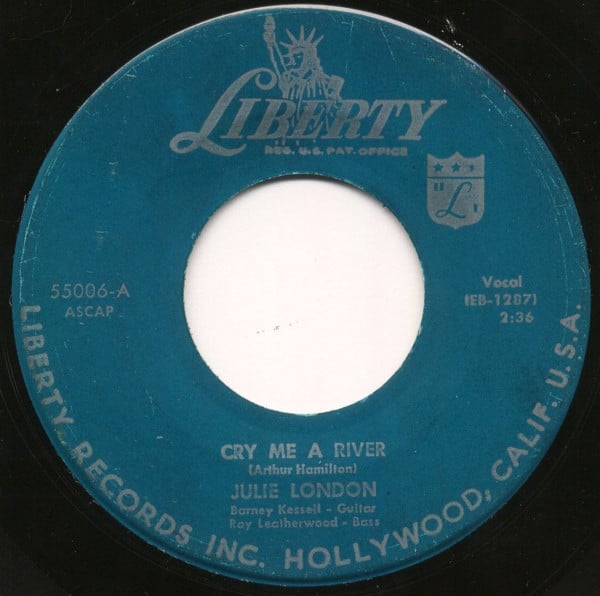

15. Julie London, “Cry Me a River” (1955)

(Hamilton) prod. Bobby Troup

Liberty F-55227 | #9 US, #22 UK

“Remember, I remember all that you said”

Another stand-in for a whole submerged genre, or collection of genres, otherwise unrepresented on this list, but on which I have previously pontificated using the coinage “adult pop,” in order to distinguish it from the teen-craze pop that is more frequently valorized from the era. I have a grudge against the widespread usage of the phrase “traditional pop” to silo off all pre-rock traditions, partly because it collapses valuable distinctions that were very much alive for the people who listened to, danced to, and played music at the time, and partly because the further into the past the Boomer irruption recedes, the less old-fashioned pre-rock music sounds; or anyway it merely sounds differently old-fashioned to the rebel rock that supposedly usurped it. The spare, dry sound of “Cry Me a River” is as sleekly ultramodern as any Sun, Chess, or Blue Note side of the day: just Barney Kessel’s sprinkled guitar and Ray Leatherwood’s slippery bass to back up London’s cool, understated delivery of Arthur Hamilton’s elegantly incisive lyric, gesturing towards beloved Tin Pan Alley tradition with the “too plebeian/through with me and” rhyme in the bridge but otherwise as plainspoken and direct as the urban blues from which the torch-song tradition was derived. It was written for jazz goddess Ella Fitzgerald to sing in Pete Kelly’s Blues but got cut by director Jack Webb; then it was offered to chipper starlet Peggy King, but middlebrow arbiter Mitch Miller vetoed it because “plebeian” was too fancy-schmancy. Finally, Webb’s wife, actress Julie London, was urged to sing it by Nat Cole-manqué Bobby Troup, who produced the session: it became a hit and formed the centerpiece of her debut album, a quintessential artifact of the early Playboy era, in which bachelor-pad sophistication, adult sexiness, and feminine autonomy could still conceivably coexist — before long, London divorced Webb and married Troup. Their collaborations, with him devising exquisite miniature settings for her limited but sensual voice, continued as a parade of intelligently sequenced albums; and when eventually Liberty assigned her other producers, she even returned occasionally to the lower reaches of the pop chart. Eventually, of course, the Sixties took their terrible toll on all adult pop, sacralizing adolescent tastes as the eternal lynchpin of the New.; her final singles were bubblegum pop covers, an indignity to which the cool, unflappable narrator of “Cry Me a River” would never have stooped.

First encounter: I don’t remember what I went to Best Buy to look for during a lunch break in 2006 or so but I do remember walking out with a copy of 1957’s About the Blues on the basis of nothing but the gorgeous cover painting and the gimmick of the track listing being all popular songs with “Blues” in the title. As was my usual habit once I “discovered” new artists, I looked them up online and downloaded their big hit — in this case, “Cry Me a River,” which shared a title with Timberlake/Timbaland song that I was only then becoming just contempo-pop-curious enough to appreciate. But feeling like I had uncovered secret knowledge (among other things, Hamilton’s lyric seems to have invented the phrase) that had been withheld from the standard histories of twentieth-century pop has always been a heady brew for me.

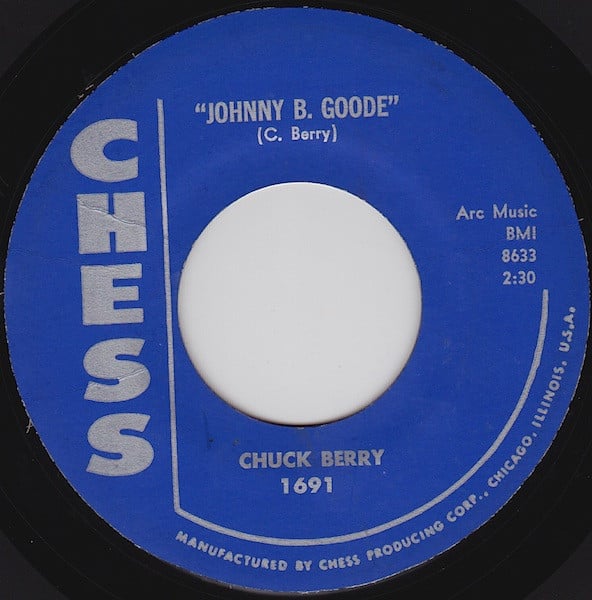

14. Chuck Berry, “Johnny B. Goode” (1958)

(Berry) prod. Leonard & Phil Chess

Chess 1691 | #2 R&B, #8 US

“Strumming with the rhythm that the drivers made”

Mythmaking is an essential part of popular music. An essential part of all culture, of course — but music is so evanescent, so profuse, so diffuse, so hard to capture and pin, wriggling, to a specimen board neatly labeled and categorized and mastered, that the myths about it often feel truer than the plain prose. A boy is born in rural poverty. He picks up a guitar and plays. (Just like yesterday.) For lack of other accompaniment, he keeps time with industrialized clatter. His mother has a premonition of glory. Sparks shoot out of the strings, cascades of notes sharper than hounds’ teeth and stronger than nylon, flowing like water, skipping like a stone, hopping backward like a one-legged duck. Go, go, Johnny go — into infinity. The prose version is only slightly less mythic. Berry changed “colored boy” to “country boy,” knowing that it would let the record cross over to white listeners. It was his eleventh single in four years, only one of which hadn’t made the R&B chart, and although originally intended to be about his usual pianist, Johnnie Johnson, like so much rock & roll to come it ended up being instead about the writer/performer — no stranger to composing in the mythic register (“Roll Over Beethoven,” “Brown Eyed Handsome Man,” “Rock and Roll Music”), he instinctively grasped the Romantic ideal of the solitary artistic genius, and helped to shaped rock music (mythologically, anyway) into an endless series of Towering Men Wielding Powerful Shafts rather than the collegial, collaborative back-and-forth that all music-making is at bottom. Which is why — in addition, of course, to a 2010s-bred distaste for his personal life — I had not listened to Chuck Berry for at least a decade until a couple of months ago, feeling a bit nostalgic for some of my old enthusiasms, I put on an algorithmic playlist inspired by “Great Balls of Fire” and found myself moved to tears on the El home from work by the mythopoeic power of “Johnny B. Goode” — not just the Local Boy Makes Good narrative, but the gleeful propulsion with which it moves forward so relentlessly, the way I knew every note before it was played but it still felt like a fresh delight when it came. There are so many more first-generation rock and roll songs I could have put here instead, but this is the one that affected me most strongly most recently, and how else would you ever determine a favorite?

First encounter: Hand to God I swear I never heard it until 1999 when I downloaded mp3s canonized by century-end lists. It was only several years later that I first watched, e.g. Back to the Future and I was already deep enough in music nerdery that I found the infamous “Marvin Berry” scene just as uncomfortable as it was funny. (Now I don’t find it funny at all.) In fact the near-exclusive association of “Johnny B. Goode” with Back to the Future for millennials and younger is part of why I loathe giving movies any credit for needle drops, diegetic or no: in my aesthetic hierarchy, music exists outside of and prior to cinema, and it is not only possible but desperately necessary to hear it on its own terms rather than as simply another piece in the Moloch-maw of Content.

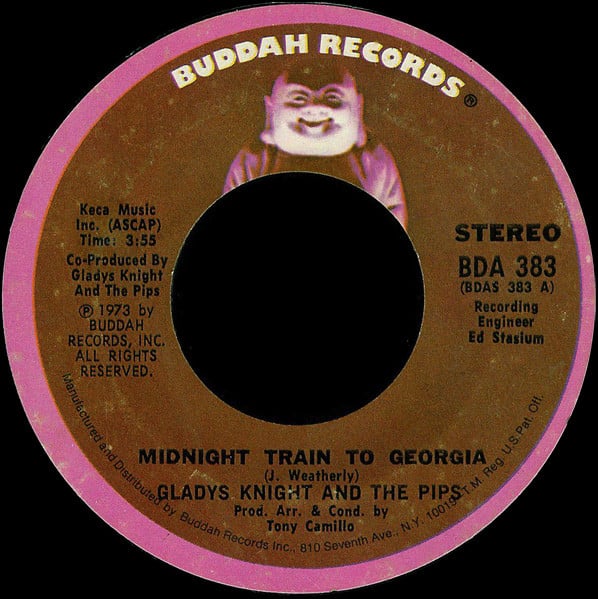

13. Gladys Knight & the Pips, “Midnight Train to Georgia” (1973)

(Weatherly) prod. Tony Camillo

Buddah 383 | #1 R&B, #19 EL, #1 US, #10 UK

“Whenever he takes that ride, guess who’s gonna be right by his side”

A country song inspired by a telephone conversation with Farrah Fawcett, originally titled “Midnight Plane to Houston” and converted to a more traditional train to Georgia at the request of Cissy Houston, whose own arrangement was still plenty country. The more important shift, though, was the gender swap: Jim Weatherly’s original about a woman who failed to make it in Hollywood is inevitably a bit condescending and paternalistic, while Cissy’s revision about a man who couldn’t hack it is far more sympathetic, if still a little maudlin. The perfection of the song under the auspices of Gladys Knight, the Pips, and Tony Camillo is that they reshape it to be a dialogue rather than a monologue: Gladys singing out Weatherly’s text in full gospel voice, while the Pips act as a sort of Greek chorus, a god’s-eye view giving us a dispassionate look at the situation that lets Gladys work herself into a frenzy of subjectivity: the cumulative effect is rather like reading first-person prose and watching its filmed adaptation at the same time. Which might sound exhausting: but Camillo’s sympathetic, march-time arrangement evoking a train pulling out of the station, each puff of trumpet another puff of steam, absorbs the listener so much that it’s a totally unified story. Not that it’s much of one even at that: but depth of narrative, rather than of emotion, is not the point of pop. And “Midnight Train” has struck such a profound chord for so long that it has almost swallowed up the entire rest of Gladys Knight’s formidable career both with and without the Pips: her first charting single was in 1961, her last in 1996, but you wouldn’t — and I certainly didn’t — know it from popular culture. Still, if any thirty-plus-year career has to be reduced to a single song, there are few better songs to be reduced to.

First encounter: I must have heard it ambiently before then, but my first memory of hearing it is on the Rhino soul comp I’ve referenced several times already. I loved it immediately, of course; but I don’t think I really understood just how totemic it was until an episode of 30 Rock used it as a narrative climax, those familiar chords and rhythms lending the show’s typical absurdity a totally unearned (and thereby absolutely hilarious) emotional resonance. In an inversion of the typical way in which audiovisual media colonizes pop music (so that, for example, multiple generations will never have any other associations with Stealers Wheel but the ones determined by Quentin Tarantino), for that brief moment television itself becomes subordinate to a forty-five-year-old record. As it should be.

12. Gil Scott-Heron with Pretty Purdie & the Playboys, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” (1971)

(Scott-Heron) prod. Bob Thiele

Flying Dutchman 26011 | did not chart

“Because black people will be in the street looking for a brighter day”

In some sharp, significant ways I am tired of this song, but not in the way you get tired of most songs. I have never heard it unless I specifically chose to play it. And I have rarely heard it since the national (and more importantly my own) awakening of political conscience that took place between Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter without feeling sorrow and rage and so, so tired. I wish apparently well-meaning people didn’t still need to be told that the revolution will not go better with Coke or fight germs that may cause bad breath. I wish NBC predicting the winner at 8:32 on report from twenty-nine districts didn’t represent the limit of so many of my fellow Americans’ political imagination. I wish I didn’t have “there will be no pictures of pigs shooting down brothers on the instant replay / there will be no pictures of pigs shooting down brothers on the instant replay” running through my head almost on a loop for the past twelve years (R.I.P. Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Philando Castile, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and far, far too many more to list). All of which is to say, I wish the song would no longer be so damn relevant. None of which is its fault. Bernard Purdie’s light soundtrack-funk, with Hubert Laws’ flute. Ron Carter’s bass, and Brian Jackson’s electric piano accompanying, sounds indelibly 1971, and Scott-Heron’s cavalcade of sardonic TV, political, and advertising references are even more of their time and place (although the Wikipedia article does pretty good at explaining them all), but the polemical point, underneath all the memes and jokes and cheap shots, remains the same as it ever was: the communications technocracy we rely on to make sense of the world isn’t going to save us. We have to do that ourselves.

First encounter: I’ve always approached hip-hop from an outsider’s perspective, never being fully immersed in any era or region or stylistic throughline, so it was as an anthropologist looking academically at the antecedents of rap that I came to Gil Scott-Heron, most likely via Allmusic once again. On my first listen, at the Bad Office Job detailed in entries #34 and #17, the record startled me with its unsparing quality, and although I would go on to try to dig out more rap ancestry in the Last Poets and U-Roy and so forth, it never shook loose from the back of my mind. It’s only grown more insistent since; I would estimate that I’ve encountered an oblique or overt reference to it roughly every two months on social media in the last decade, whether by people trying to corral a particular version of the revolution or by people mocking those who think that posting (like this) is revolutionary.

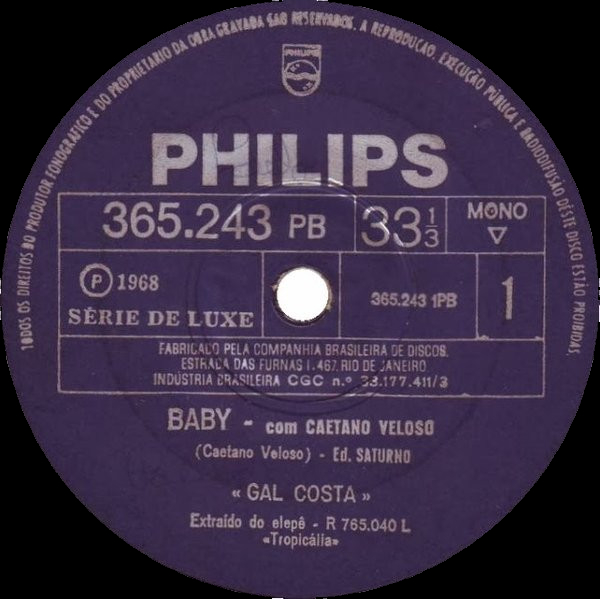

11. Gal Costa com Caetano Veloso, “Baby” (1968)

(Veloso) prod. Manoel Barenbein, arr. Rogerio Duprat

Philips 365243 | #3 BR (year-end)

“Vivemos na melhor cidade da América do Sul”

One of the things about getting into trópicalia just as I was making a poptimist pivot in the rest of my music listening is that psych rockers like Os Mutantes, writerly auteurs like Caetano Veloso, and arty experimentalists like Tom Zé got far less headphone time than Gilberto Gil’s soulful afrocentricity and Gal Costa’s expansive chanteuserie. Costa’s two 1969 self-titled albums in particular are still the Portuguese-language albums I’ve spent the most cumulative time soaking in, even after having spent the last decade deep into contemporary urban Brazilian, Portuguese, Angolan, Cape Verdean, and Mozambican pop. There were enough psych freak-outs, writerly lyrics and arty experimentalisms on those LPs to satisfy ny latent rockist in any case. But as far-out or intense as she could get, this song, originally released on the Trópicalia, ou Panis et Circencis multi-artist manifesto album, has always overwhelmed me with its lush beauty. Rogerio Duprat’s swooping, blissed-out string arrangements, modernist in scope and volume without neglecting pop melodicism, flutter over a bed of skeletal bossa nova while Costa sings Veloso’s lyrics about political consciousness, rapprochement with American cultural imperialism, and giddy romanticism in a voice as clear and cool as a rainforest stream. “We live in the best city in South America, in South America” she sings, like a tourist brochure — or like someone in love, for whom everything immediate is sacralized. When Veloso’s voice joins her in counterpoint for the final chorus, it’s less as a duet and more as a steadying background presence, an inversion of the typical usage of female background singers in all-dude rock bands.

First encounter: One last time: Pitchfork’s 200 Best Songs of the 1960s, on which “Baby” ranked #79 — characteristic of the site’s mid-00s solipsism, the blurb frankly confesses to knowing nothing about the lyrics, and guesses exactly wrong. I also didn’t know what she was singing about the first hundred or so times I listened to the song, even when I named it my 7th favorite 60s song a few years later. But in the interim I’ve done enough app-based language learning to read Portuguese at a fifth or sixth grade level and “Baby” has only grown in beauty since discovering that the luscious romanticism is only the climax of a series of demands for political, economic, aesthetic, cultural, and nationalistic enlightenment.

10. The Kinks, “All Day and All of the Night” (1964)

(Davies) prod. Shel Talmy

Pye 7N-15714 | #7 US, #2 UK

“The only tiiiime I feel alriiight is by your siiiiiiide”

I experience a mild form of synaesthesia when it comes to music, usually prompted by whatever visual cues a given piece of music might have associated with it, like album art, disc labels, music videos, YouTube thumbnails, or band photos on blogs. So for the past five or so entries in this list, the tints in my head as I listened through them have run something like desaturated, shadowy blue tones for “Cry Me a River,” wiry hot orange lines scrawled on a neutral background for “Johnny B. Goode,” painterly purples and grays for “Midnight Train to Georgia,” muted greens and yellows on faded 70s film stock for “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” deep greens bursting into spots of vivid gold for “Baby,” and now bright violent reds peeling into ragged browns at the distorted edges of each power chord. It’s no coincidence that the Kinks’ 1964 self-titled album cover is in shades of red and brown, because that would have been in my head when I first listened to “You Really Got Me” and then would have carried over for the extreme similarity of “All Day and All of the Night.” Why I like the Kinks’ fourth single better than the third — or, apparently, than any other, since it’s here — is a question I’m not sure I can answer, except that Dave Davies’ thick, overdriven guitar crunch from the early period felt like a necessary sound to have represented on this list, and Ray’s slightly more wistful focus on emotional yearning here, rather than the pure horndog desire of “Got Me” (on which I can never quite get David Lee Roth out of my head) more exactly fits what I want to get out of the Kinks. The Kinks have been my favorite British Invasion-era band for as long as I’d listened widely enough to have one, and if this record is (almost) the last concession on this list to the rock-centric origins of my obsession with popular music history, it feels right and proper to have them at their most direct, plaintive, and LOUD, instead of the twee-er, more observational (not to say parochial) material that tends to be lauded in exercises like this one. I’ve loved “Dedicated Follower of Fashion” and “Waterloo Sunset” and “Days” and all the rest of them, including most of the 66-72 run of albums, too — but the neanderthal impulse in rock, Whitman’s barbaric yawp, deserves its moment in the sun, even if it’s no longer central to my conception of good music.

First encounter: The Kinks would have been the fourth 60s British band I downloaded mp3s from way back around the turn of the millennium, after the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Who. Their name vaguely scandalized and tantalized me, but “Lola” aside I never found that any of their work particularly lived up to it. I remember trying to evangelize my growing interest in rock history to my younger brothers around that time, saying that bands like the Kinks and Led Zeppelin represented a (historically situated, admittedly) extreme of heaviness, but they just looked at me like I was insane and cited Disturbed. That conversation has stuck with me ever since as a reminder that my default desire to hear music within at least a rough model of its historical context is not just unusual but alien to most of my peers, especially the further back into history it goes.

9. Vince Guaraldi Trio, “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” (1962)

(Guaraldi)

Fantasy 563X | #9 EL, #22 US

“🎶🎵🎶🎵🎶🎵”

The first jazz piece on my list since #50, and the only wholly instrumental piece at all. Since compiling this list, I’ve been working on compiling a further 50 lists of 50 singles 1954-76, each dedicated to a specific genre, and the jazz one was the first one I finished. Even despite the greatness of every record on that list, though, I think “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” is still my favorite, in great part because no edits were necessary to squeeze it onto one side of a 45. It’s a pop-jazz tune, certainly, belonging as much to the broader instrumental pop wave of the late 50s and early 60s (one of many fads the U.S. charts entertained in the interregnum between Elvis and the Beatles) as it belongs to jazz proper. A few years too late for cool-jazz hipsterdom, a few years too early for a bossa nova cash-in, the easygoing product of a man content in later years to be best known for his gentle scores for a series of oddly subdued holiday specials adapting a neurotic, melancholy comic strip — “Cast Your Fate to the Wind” remains a singular oddity even in its own idiom, the piano–bass–drums trio formation that gave the world some of the most popular work by artists like Art Tatum, Nat King Cole, Bill Evans, Oscar Peterson, or Ahmad Jamal. Guaraldi is the only member of the trio to take a solo, and even that bears more resemblance to the wander of a thought before being recalled to a pleasant present than any kind of exploration. But when you’ve written a melody that gorgeous, who can blame you for not wandering away from it for long? One of only two original compositions from Guaraldi’s album Jazz Impressions of Black Orpheus, the first American response to Antônio Carlos Jobim and Luiz Bonfá’s soundtrack for Orfeu Negro (itself ground zero for the bossa nova explosion), it’s not exactly a samba, but not exactly not one either — it was called “calypso-tinged” in press at the time, but Colin Bailey’s rustling brushes on the drums are more atmospheric than rhythmic: it’s Guaraldi’s left hand that sets the gentle, water-lapping pace.

First encounter: I may have heard it at some point before 2015, but that is the earliest I can find myself posting about it, which in the social media era’s best substitute for memory. I spent a lot of 2013 to 2015 in a deep depression occasioned by solitude and un(der)employment, and one of the few reliable solaces that got me through it was cuing up an extraordinarily beautiful record and listening to it on repeat. The 1930 Brunswick recording of the Duke Ellington Orchestra’s “Mood Indigo” was one; this was another. Lighter and airier than Ellington, it represented a slow thawing of my own mood; and it still sounds like spring after a long cold lonely winter.

Next week: #8-1, in which the the final entry might match the wordcount of all the rest.